Frederick Tudor (Fred, F. T.) Scripps was born in 1850 in Rushville, Illinois. His widowed father had emigrated from England with six children from his previous marriages (among whom was Ellen Browning Scripps), married again, and raised five more children in the Rushville area. Fred was the third of these children; the youngest, Edward Willis (E. W.) Scripps, born in 1854, went on to establish a newspaper empire which eventually became the E. W. Scripps Company, a media conglomerate which exists to this day. While E. W., Ellen and her brother (his half-brother) James were prospering in the newspaper business, Fred remained a farmer in the Rushville area. He was described as the ‘problem’ sibling in the Scripps family; never settling on a career, moving from one venture to another, and losing money along the way. Nevertheless, the Scripps family remained close and in 1890 Fred and Ellen travelled to California to visit his sister (her half-sister) Annie who had moved to Alameda for her health. After a month in northern California Fred and Ellen traveled to San Diego to visit cousins and spent some time traveling around the region, including Pacific Beach and La Jolla and the undeveloped land east of these suburbs that was then called Linda Vista.

Both Ellen and Fred were impressed with the San Diego area, particularly Fred who, like his sister Annie, suffered from arthritis and felt that he would benefit from the milder climate. They convinced E. W. to visit later in the year and he also liked what he saw and agreed to join Ellen in purchasing property in Linda Vista. They began by purchasing three tracts of land totaling 400 acres north of Carroll Canyon, extending east from about where Interstate 15 runs today. Fred sold his farm in Rushville and moved to San Diego to oversee development of the new Scripps estate. Construction of a palatial home on the property, which E. W. Scripps named Miramar, began in 1891 and proceeded throughout the decade; when completed in 1898 it had grown to 49 rooms.

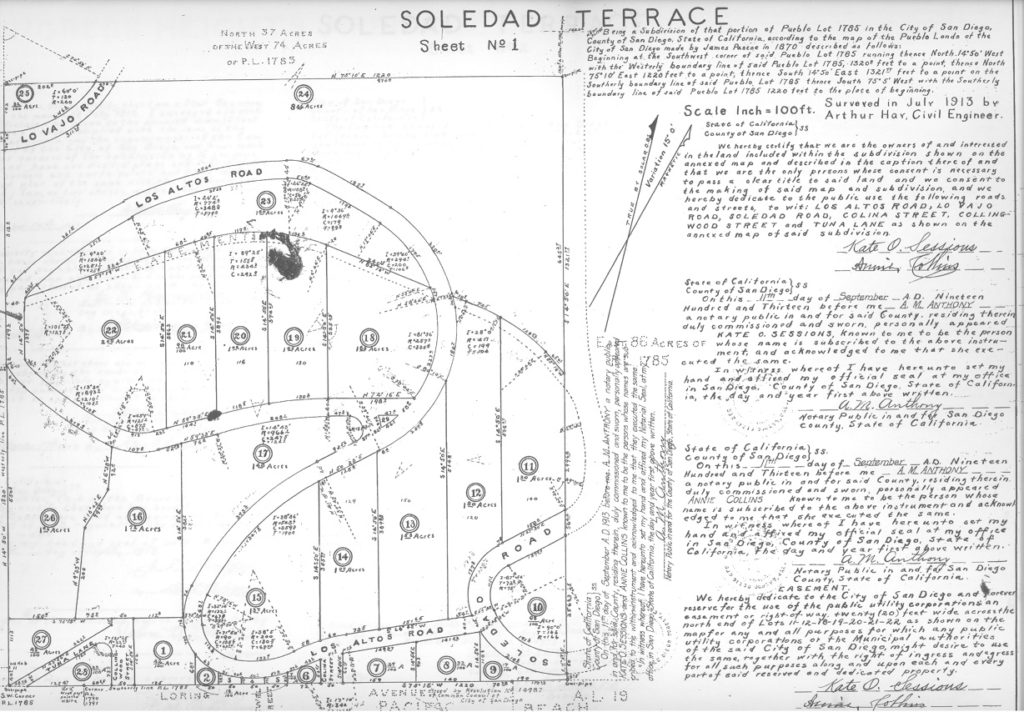

Sarah Emma Jessop was born in England in 1871. Her father, Joseph Jessop, a jeweler, had been told by his English doctor that his ‘chances for health’ depended on moving to Southern California. His doctor also prescribed a change of careers, giving up his jewelry business in favor of the outdoor life of a rancher. Accordingly, the Jessops moved to San Diego County in 1890 and bought a 50-acre ranch in Linda Vista, a location which is between today’s Black Mountain Road and Interstate 15, north of Miramar Road and south of Carroll Canyon Road. The Jessops and the Scripps thus became neighbors; the northeast corner of the Jessops’ property met the southwest corner of the Scripps’. Fred Scripps and Emma Jessop became acquainted and in December 1893, when he was 43 and she was 20, they were married.

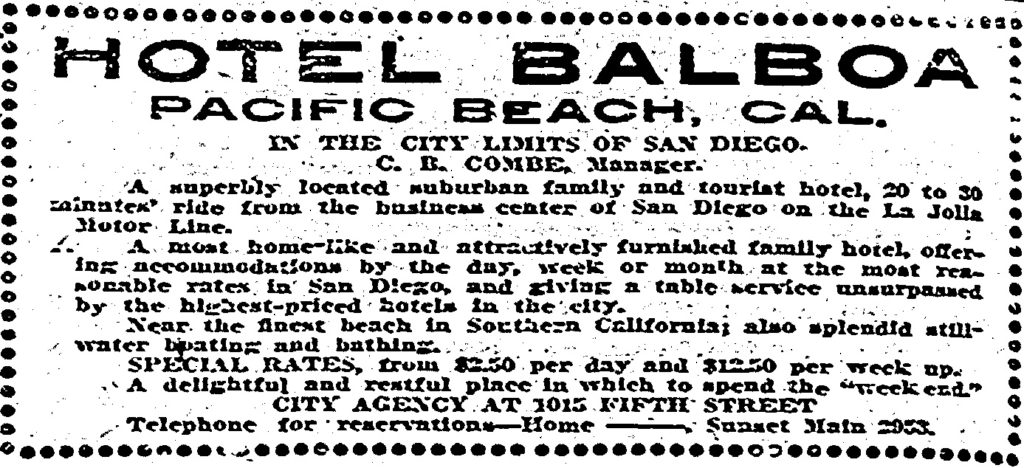

E. W. and Ellen Scripps had intended for their ranch to become a home not only for themselves but also for other members of their extended family, but even with the addition of separate wings it apparently was never large enough for all of them. Ellen was the first to leave, beginning her long association with La Jolla when she bought property on Prospect Street in 1896. Fred and Emma followed soon after, purchasing property on the shore of Mission Bay and building their bay-front home Braemar Manor.

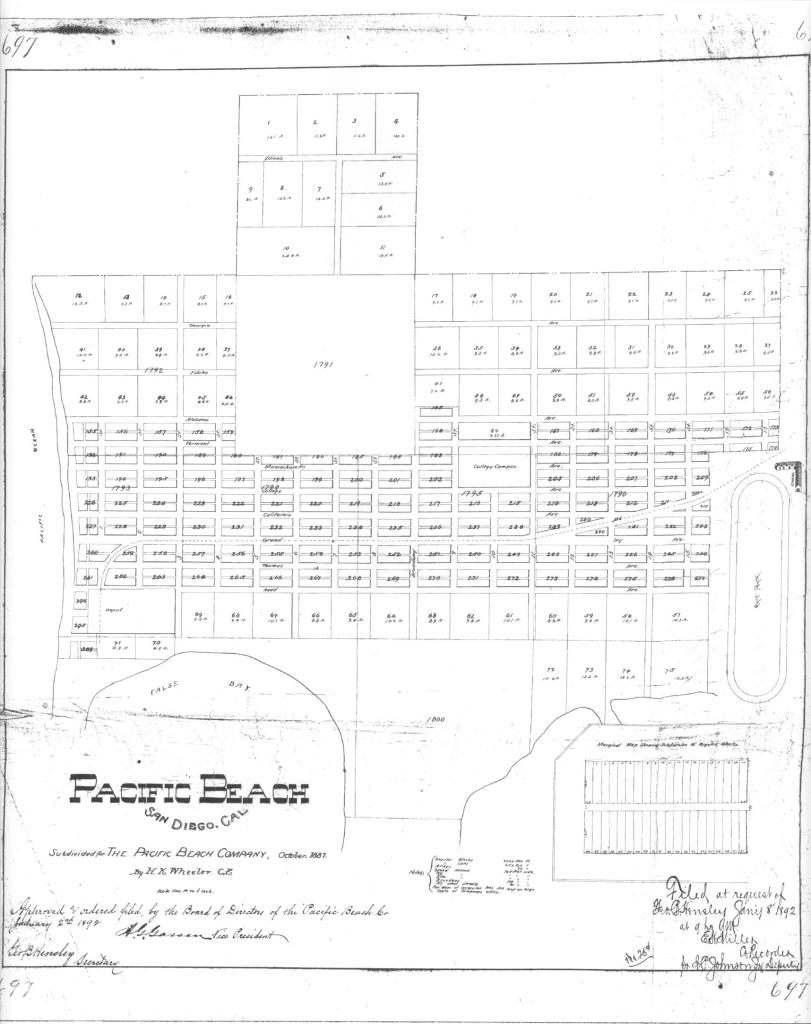

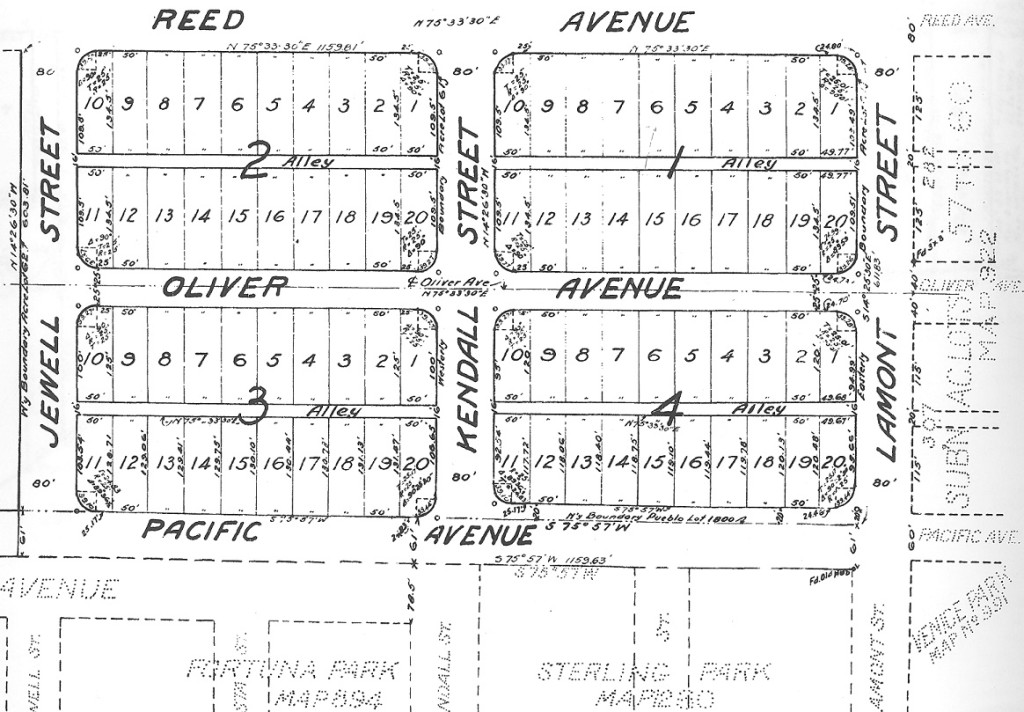

The land at the northwest corner of Mission Bay had once been the property of James Poiser, who had raised sheep there and watered them at freshwater springs in the area. Poiser had purchased 40 acres in the north end of Pueblo Lot 1803 from Alonzo Horton in 1885 and was among those whose land was acquired by the Pacific Beach Company in 1887. Poiser’s deed granted the Pacific Beach Company his 40 acres ‘excepting therefrom 1 acre previously sold, and one acre around the house now occupied by me to be taken off the end of any block that may be laid out to cover said ground’. On a map of the Pacific Beach subdivision recorded at the end of 1894, Map 791, this property had become Acre Lots 70 and 71, Blocks 387 and 389, and ‘Poisers 1 Acre’.

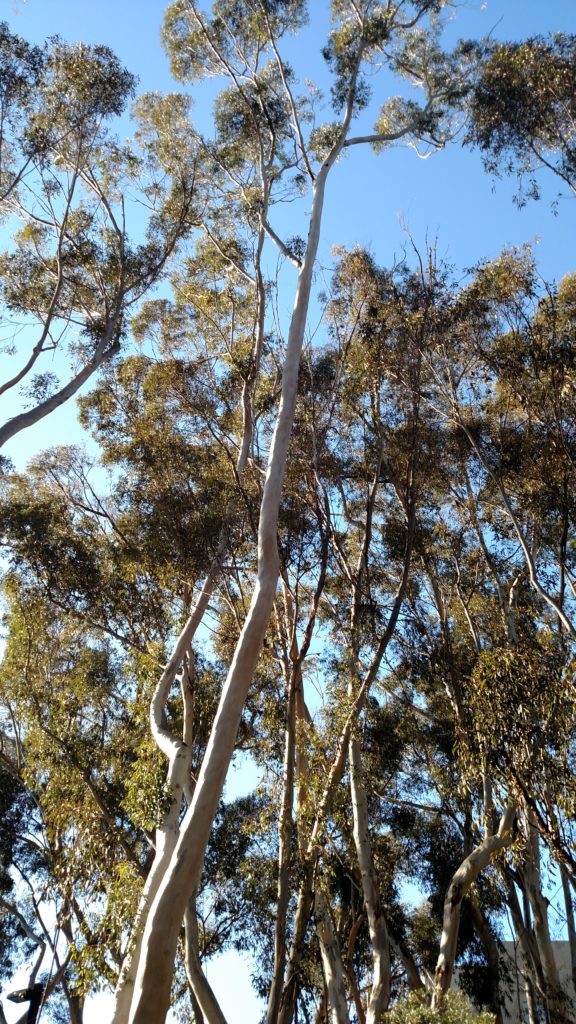

The bayside Poisers 1 Acre tract passed through the hands of several other owners before F. T. Scripps acquired it in December 1899. He also bought Acre Lot 71, at the southwest corner of the streets that became Bayard Street and Pacific Beach Drive. Scripps wasted little time developing his property; the San Diegan – Sun newspaper (owned by E. W. Scripps) noted in October 1900 that ‘F. Scripps is making a fine home on the old Poiser place near the bay. The inside finish of his house is of white cedar. He has also a fine, commodious barn, wharf and all conveniences of a seaside home’. Landscaping of the 7-acre site was also underway; the Evening Tribune reported in November 1900 that Mr. Scripps was improving his place at the ocean front by putting in roses and bulbs.

By the end of 1901 the home had become ‘Mr. Fred Scripps beautiful residence on the bay’. Early photos showed a large two-story home with a central gabled section which featured a balcony overlooking the bay, dormer windows to each side and a covered porch extending the full width of the building on the bay side. The Scripps’ home was notable not only for its size and architecture but also for its landscaping. Emma Scripps was an avid gardener and, with Kate Sessions, one of the founding members of the San Diego Floral Association in 1907. In an article she wrote for the association journal The California Garden in 1909, Mrs. Scripps figuratively led visitors through her garden, from a ‘geranium walk’ to beds of asters, penstemons, dahlias and a glorious bed of gladiolus flowers, over 600 bulbs, each with a stem of cherry-red blossoms 18 inches in length and all in bloom at the same time. There was also a bed of chrysanthemums, a Japanese garden, and flat stepping stones picked up on the beach leading through a pergola of cypress logs.

Mr. Scripps went on to purchase and subdivide other tracts of land between his home on Mission Bay and Ellen’s home in La Jolla, becoming prominent as a real estate developer. His holdings included the Braemar subdivision adjacent to his home, the Ocean Front subdivision between Diamond and Chalcedony streets, and F. T. Scripps Addition to La Jolla Park, between Marine and Westbourne streets in La Jolla (which included Rushville Street, named for his home town). He was also instrumental in improving the road connecting his properties that became La Jolla Boulevard.

Mrs. Scripps belonged to a number of community organizations, including the Pacific Beach Reading Club, and frequently hosted these groups’ meetings in her home. The Scripps property was also the scene of elaborate public events to benefit causes which Mrs. Scripps supported. In 1910 the San Diego Floral Association cordially invited the public to the beautiful garden of Mr. and Mrs. F. T. Scripps, at Brae Mar, which would be converted into Fairyland for the benefit of the Talent Workers’ Hospital fund. The garden would be decorated in the most lavish manner and there would be Japanese and oriental refreshment booths, a flower booth, fortune teller’s booth, candy booth and apron, fancy work and tooled leather booths. The San Diego Union added that the booths would be filled with bright articles, not the least of these being the ‘pretty and popular girls’ who would be in charge of them. ‘Misses Violet, Fanny and Linda Jessop, sisters of Mrs. Scripps, are to meet the guests and look after their welfare generally’.

In 1914, Mrs. Scripps invited the Floral Association to Braemar Manor for an outdoor meeting. The California Garden reported that whereas the only living things on the place when the Scripps took possession twelve years before were a few cypress trees and Bermuda grass, today the grounds were surrounded with double rows of Phoenix Canariensis palms, ‘large and sturdy in appearance’. Here and there were various out-buildings, including a substantial wigwam built by ‘real red men’ and filled with numberless Indian relics and curios. There was a lath house, rich in ferns and tuberous begonias and a luxuriant grapevine formed an arbor which the sun could not penetrate. On the bay front were other summer houses, including a Japanese teagarden and a little log hut. Florally, despite sitting just off the ocean front and with sandy soil, Braemar had produced creditable blooms of almost every flower family. Mrs. Scripps’ roses had long been famous through having won many ribbons and cups at the flower shows.

In 1921 Miss Annie Scripps, the Scripps’ youngest daughter, married Austen Brown, a graduate of the Army and Navy Academy in Pacific Beach. The wedding took place at ‘Brae Mar Manor, the Scripps home in Pacific Beach’ and was solemnized in the conservatory of the home. The Tribune reported that the bride looked very pretty in her white velvet gown and veil, and her sister Miss Mary Scripps, set her well off in a charming dark frock. The roles were reversed two years later when Mary Scripps married William Gardner Corey, son of Pacific Beach pioneer Dr. Martha Dunn Corey, in July 1923. That wedding took place at Saint James-by-the-Sea in La Jolla with Mrs. A. G. Brown (nee Annie Scripps) as matron of honor, followed by a wedding reception at the home of the bride’s parents in Pacific Beach.

Braemar Manor had always been an impressive residence but in the mid-1920s it underwent an extensive renovation which included both new construction and a change in style. The new construction included the addition of a dining room with an arched ceiling that was attached to the west end of the estate (and which is the only surviving portion of the home, although now in a different location). The new dining room was finished in the then-popular half-timbered look with leaded windows called English cottage style, and the original portions of the house were also upgraded with leaded windows, towering brick chimneys and exposed exterior woodwork to match.

Scripps also took steps during 1926 to make the surrounding neighborhood more to his liking. In May the Common Council adopted a resolution closing the half-block of Bayard Street that had continued south of what is now Braemar Lane. The property east of the closed portion of Bayard Street was divided into three parcels fronting on Mission Bay which were distributed to three of the four Scripps children (F. Tudor, Jr., the youngest, was only 18 at the time). Thomas Scripps, the oldest, received the western-most lot, separated from his parents’ property by the closed portion of Bayard Street, and his own bayside home was completed by the end of the year. The closed portion of Bayard Street effectively became a private drive into the grounds of the Scripps compound.

The upgrades to the Scripps’ property were followed by even larger and more elaborate social and community events. In June 1926 Emma Scripps and two of her sisters gave an elaborate garden tea in honor of their other sister, Fannie, Mrs. Frederick C. Sherman. Mrs. Sherman was moving to Long Beach soon to join her husband, who was an officer aboard the battleship USS West Virginia. The Union reported that the affair, to be given at the Scripps’ home, Braemar, at Pacific Beach, would present a lovely setting with colorful awnings and umbrellas throughout the gardens, and on the beautiful strip of beach which adjoined the garden. An orchestra would provide special music during the afternoon on the spacious lawn.

In 1928 the Scripps’ neighbors, the ZLAC Rowing Club, needed funds to build a clubhouse and money was raised by selling tickets to a May fete in the ‘beautiful and spacious gardens of Mrs. F. T. Scripps who is now an honorary member of the club’. According to the Evening Tribune, the garden fete at the Fred Scripps home in Braemar on June 2 was one of the most important social functions of the season; ‘The Scripps gardens are among the show places of San Diego, and include many interesting features, among them being the log cabin, where a dark mammy will tell fortunes; an adobe house built by the Indians of Mesa Grande, and an unusually attractive lath house’.

A year later, in April 1929, the Union announced that Brae Mar, the charming home of F. T. Scripps at the head of False Bay, with its colorful gardens and walks, had again been chosen by the ZLAC Rowing Club as the setting for its annual garden fete. In addition to an open air dancing pavilion, a crystal gazer to read fortunes, a Japanese tea room and a novel Indian house, special entertainment for children had been planned; ‘On the Scripps private beach is a replica of the Mayflower and around this boat will be treasure hunts, ponies to ride, and story tellers to interest the little ones’.

By 1931 the ZLAC fete had become a ‘brilliant function’ on the ‘social horizon’ of the ‘elite sets’ in San Diego. The Evening Tribune heralded the Fourth Annual Garden Fete of the ZLAC Rowing Club as the most important of forthcoming affairs; ‘Ever since the first Garden Fete was given four years ago, this function has climaxed the social activities of each Spring season’. The outstanding feature of the afternoon’s entertainment was expected to be the Tom Thumb Wedding in which the little four- and five-year-old sons and daughters of older ZLAC members were to come down through the Grape Arbor to the open garden where the ceremony was to be solemnized. After the event the Tribune reported that the colorful garden fete in the beautiful gardens of Mrs. Fred T. Scripps at Braemar had been one of the most successful ever, with over 1500 guests and over $1000 collected for the new club house fund. An unusually large number of children were present to enjoy the pirate ship, puppet show and Tom Thumb wedding. Miss Ann Packard and her twin sister Mrs. Norman Karns, members of ZLAC crew 11, were in charge of the exciting pirate ship and Myra Rife Smith, another ZLAC member, was the veiled fortune teller.

ZLAC garden fetes were held again in 1932 and 1933, described as the opening event of the early summer season which marked the beginning of the highly enjoyable out-of-doors events which made summer a season of gayety. No fete was held in 1934 however, and in 1935 the Union noted that while Garden Mayfairs are in San Diego’s social tradition, the ZLAC Rowing Club had given up its annual garden party in May at Braemar. Fortunately, the Neighborhood House was carrying on the tradition by opening the George Marston gardens each springtime for a similar fete.

The end of the ZLAC fetes did not mean an end to other social events on the Scripps estate, which included gatherings of the Scripps’ and Jessops’ large extended families. In September 1935 the San Diego Union carried a photo spread (‘Young Society Splashes in Good Old Summertime’), showing cousins Billy Corey, Mitch Corey and Carroll Scripps ready for a slide at Braemar, Carrington Corey, Jack Sherman, George Jessop and Tommy Scripps being taught to swim, and Virginia Corey ready for a plunge, at the home of their grandparents in Pacific Beach.

Frederick T. Scripps died at the age of 85 in January 1936. The brother of the late E. W. Scripps and the late Ellen Browning Scripps was said to have lived quietly, devoting himself to his family and real estate activities. His widow, Emma, remained on the family estate for many years and continued the tradition of gracious entertainment for the community. In July 1936 the Union reported that many of the same attractions seen at the ZLAC affairs were again put to use for a charming English garden fete arranged by the Pacific Beach Presbyterian Church in the lovely bayside home of Mrs. F. T. Scripps; ‘booths and tables common to this sort of outdoor fair, fortune tellers of mystic powers, pirate ship and treasure chest attractions for the youngsters, wandering troubadours and Spanish and Mexican dances on the green’. Refreshments would be served in the music room with the assistance of a group of ‘charming sub-debs’.

In 1937 the lovely gardens of Mrs. F. T. Scripps at the foot of Bayard Street in Pacific Beach were scheduled to be the scene of one of the prettiest garden parties of the opening of summer, this time under the auspices of the Pacific Beach Women’s Club. Again, fortune tellers would peer into the future and would reveal what is in store for inquirers and there would be a fish pond and puppet show and treasure chests for the youngsters aboard the old ‘pirate ship’ which stood on the water’s edge of the big estate which borders Mission Bay. The Union even carried a photo of Little Miss Annie Linda Brown and Miss Diana Scripps, cunning granddaughters of Mrs. Scripps, contemplating the beauty of the garden as they planned which of the many exciting things to interest small folk they would patronize at the garden party the following afternoon.

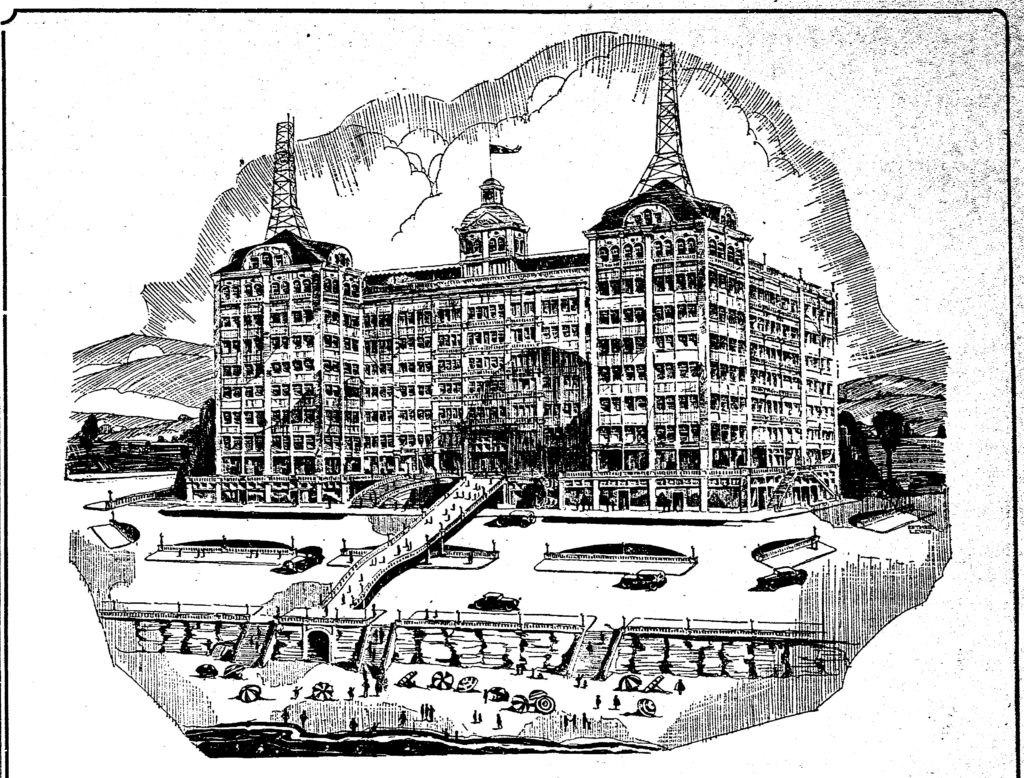

Mrs. Sarah Emma Scripps continued to live at Braemar until her death in September 1954. The 7-acre estate was then acquired by Vernon Taylor and Clinton McKinnon, who began the process of rezoning so that a 3 million dollar hotel could be constructed on the property. Braemar Manor was razed in 1959 and construction began on the Catamaran Motor Hotel, an ‘oriental-styled modern hostelry’ on Mission Bay, with completion anticipated for early summer. In January 1960 the Union’s society columnist attended a party at the new hotel on the site of the ‘Stratford manor house of the late Mr. and Mrs. F. Tudor Scripps’ and reported that the dining room (with cathedral arches) was being developed as a wedding chapel and the Old English garden, setting for the ZLAC fairs of two decades ago, had become severely simple Japanese walks paved with grey beach pebbles from Mexican beaches.

Weddings at the Catamaran Wedding Chapel began in 1962 and were popular until the chapel was again moved to make way for a parking garage in 1986. The building was donated to the Pacific Beach Town Council and moved to a site on the other side of Pacific Beach, a ‘useless and vacant lot’ owned by the Navy on the south side of Garnet Avenue, across from Soledad Mountain Road and bordering Rose Creek. The site had been acquired by the government as part of the wartime Bayview Terrace public housing project and later transferred to the Navy for its Capehart housing project. Nothing was ever built on that particular parcel and the Navy offered to lease the property as a community service. Now known as the Rose Creek Cottage, it is still available for weddings and other special events.

While nothing else remains of the F. T. Scripps family’s presence in Pacific Beach, the enduring legacy of the extended Scripps family is familiar to most San Diegans. E. W. and Ellen Browning Scripps provided support for the Marine Biological Association laboratory in La Jolla in 1903; the lab later merged with the University of California, becoming the Scripps Institution for Biological Research, then, as the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, was the foundation of the University of California, San Diego campus in La Jolla. Scripps Hospital and Scripps Metabolic Clinic, established by Ellen Scripps in 1924 and originally located near her home in La Jolla, have evolved into Scripps Health, now considered San Diego’s premier health care provider. Ellen Scripps and her sister Virginia also supported The Bishop’s School, founded in 1909, again near her home in La Jolla, and which is still one of San Diego’s, and the country’s, top independent college-prep schools. In 1926 Ellen Scripps founded Scripps College, a women’s liberal arts college on the Claremont Colleges campus in Claremont, California. Miramar, the Scripps’ ranch and their first home in the San Diego area, gave its name to the nearby military air station and the development that grew up around it and when the ranch itself was sold by the Scripps heirs in the 1960s the residential community built on the property was named Scripps Ranch.

The Jessop name is also still remembered in San Diego. Disregarding his doctor’s advice, Joseph Jessop gave up the outdoor life of his ranch in Linda Vista and opened a watchmaking and jewelry shop on F Street downtown. Jessop Jewelers became a San Diego institution and was still operated by the Jessop family until 2018, when the last shop was closed. Jessop’s watchmaking background was memorialized in a 24-foot-tall street clock built over a century ago that had stood outside Jessop Jewelers on Fifth Avenue and more recently in Horton Plaza shopping center. The clock was vandalized and removed from the mall for repair in 2019 but Jim Jessop, Joseph’s grandson, has announced that it will be restored and put on display at a new location.