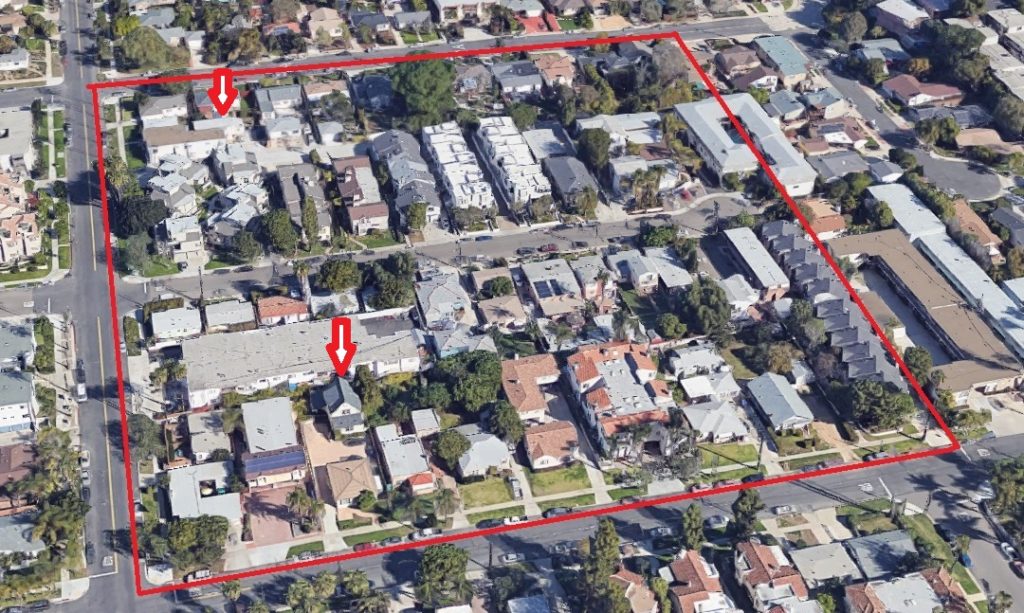

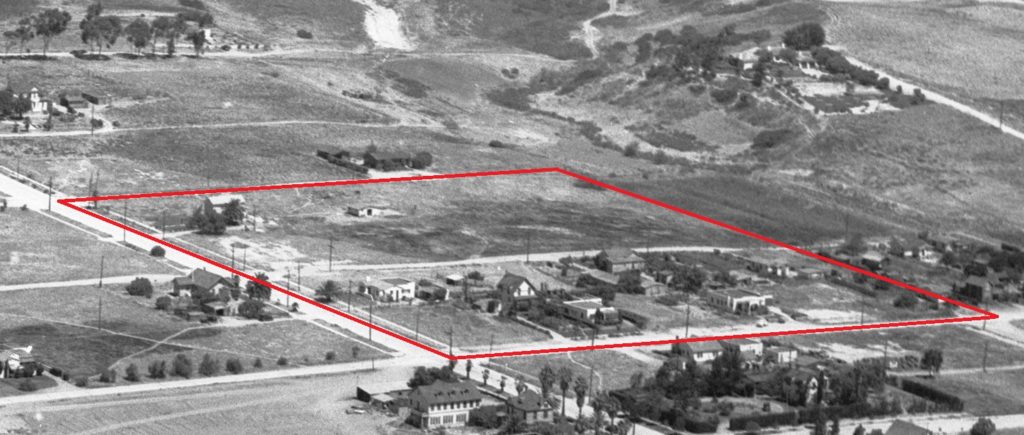

In February 1892 R. C. Wilson and G. M. D. Bowers, brothers-in-law and business partners from Henning, Tennessee, purchased Acre Lots 34 and 50 of Pacific Beach and in March 1892 added Acre Lot 33, lots that met at the corner of what are now Chalcedony and Lamont streets. The price was $100 an acre; $1850 for lots 34 and 50 and $990 for lot 33. These acre lots originated in an amended subdivision map recorded by the Pacific Beach Company in January 1892 that partitioned Pacific Beach north of Diamond Street (and south of Reed Avenue) into ‘acreage lots’ of approximately 10 acres, intended for agricultural use. By the end of March 1892 a six-inch water main had been laid up Lamont as far as Chalcedony and the San Diego Union reported that Wilson and Bowers were having 4,000 feet of water pipe laid over their 30-acre tract. The Union added that the property was to be put in lemons during the next few weeks. Other purchasers also acquired acre lots in the vicinity and Pacific Beach soon became a thriving center of lemon cultivation. On Acre Lot 34, west of Lamont between Chalcedony and Beryl streets, the Bowers built the first lemon ranch house in Pacific Beach in 1892, a house which is still standing at 1860 Law Street. The Wilsons built in 1893 on Acre Lot 33, on the other side of Lamont. Their ranch house was razed in the 1940s but a large Moreton Bay fig tree that once stood over it still marks its location.

In 1895, having developed their properties into a profitable lemon ranch, the partners sold them and returned to Tennessee. Lot 33, including the Wilsons’ home, was sold for $5500, lot 34, with the Bowers’ home, also sold for $5500 and lot 50, with no improvements at the time, went for $3000. The purchasers of Acre Lot 50, east of Lamont Street between Chalcedony and Diamond streets, were Lewis and Elizabeth Coffeen, recent arrivals from Michigan. They built a ‘fine cottage’ on their new possession which the city assessed at $100 and in December 1895 the Union reported that they had moved into their new house. This house is also still standing, at 1932 Diamond Street. However, the Coffeens did not live in the fine new cottage for long; he was compelled to return east for business reasons and the ranch was sold in March 1897 to Major William D. and Henrietta Hall.

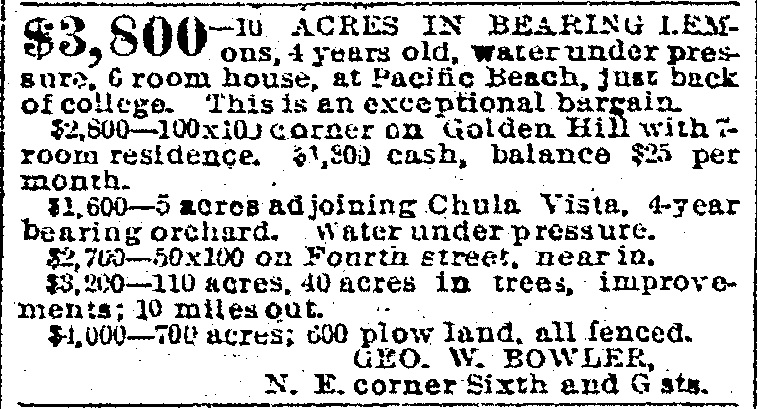

According to the Union, Maj. Hall, a new arrival who spent three years in Phoenix, Ariz. seeking restoration to health, was induced to visit Pacific Beach to examine a ten-acre improved tract by an advertisement in the Union. Three days after first sight, Maj. Hall was the proud possessor of a four-year-old lemon grove, beautiful for situation, commanding a view of Mission Bay, the breakers at Ocean Beach, Point Loma, San Diego city and Coronado. He had already erected a curing house and had a hundred boxes of lemons packed therein. Maj. Hall was reportedly delighted in the soil, location, climate and environment and especially the price of water, for which he said he paid as much for his ten acres as he would have paid for an acre and a half in Phoenix. At the end of 1897 the Union reported that Maj. Hall had received $200 from the abandoned orchard that he took charge of ten months earlier and in June 1899 it reported that he netted $100 from a picking of four acres of lemons. Presumably he used the proceeds for the ‘quite important additions and improvements’ made to his house in December.

On New Year’s Day the San Diego Union regularly featured articles celebrating each of the outlying communities and on January 1, 1900, the article from Pacific Beach was written by Wm. D. Hall. According to Maj. Hall, Moses’ view of the promised land from Mount Pisgah could not be compared with the view of Pacific Beach from Point Loma, and nearly in the center of this beautiful spot were clustered about three hundred acres of lemon groves from three to seven years old and from 2 ½ to 10 acres, dotted here and there with fine residences with well kept yards, beautiful with every variety of flowers and in bloom all year round. He noted that the Pacific Beach lemon groves were not only attractive but productive; during the past year thirty carloads of lemons (and two of oranges) had been raised and shipped. However, like Wilson and Bowers, Maj. Hall apparently decided that there was more profit to be made selling the groves than the lemons and in 1899 the Halls sold about half of Acre Lot 50, the northern 298 feet, with 12 rows of trees running east and west, to A. F. and Margaret Roxburgh. In 1901 the Halls sold the other half, the southern 322 feet including their home, to R. M. Baker.

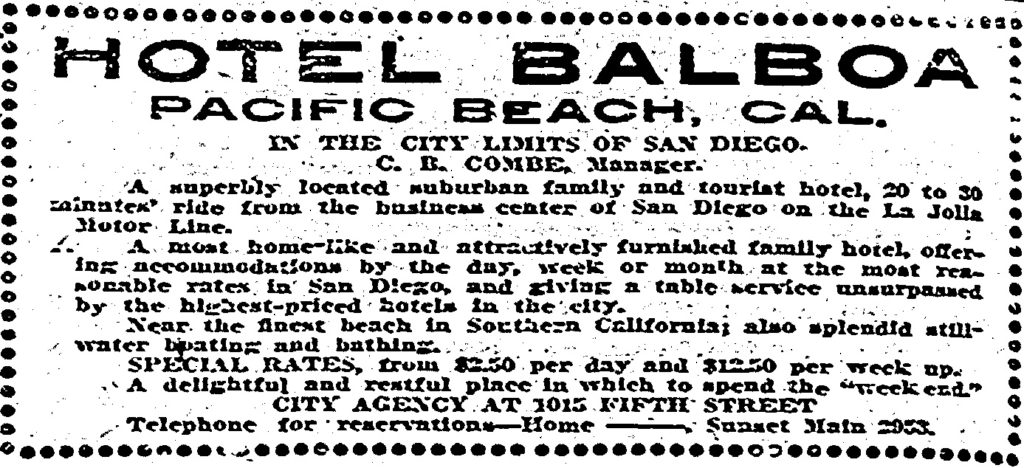

The Roxburghs were from Scotland and had come to Pacific Beach to join her brother William Kyle who had established a poultry ranch in Pacific Beach, specializing in ducks. Kyle was also an elder and Sunday School superintendent at the Pacific Beach church; the Union reported that the Santa Claus who entered through a church window and distributed gifts to the children on Christmas Eve in 1896 had a broad Scotch accent. His sister and her husband arrived in February 1899 and in June of that year Mr. Kyle’s and Mrs. Roxburgh’s mother also arrived from Scotland. Kyle, his mother and the Roxburghs initially rented rooms at the College Inn, originally the home of the San Diego College of Letters but used as a rooming house after the demise of the college in 1891. Once they had acquired their ranch in the north half of Acre Lot 50 the Roxburghs moved out of the inn and for several years lived in houses on neighboring lemon ranches including Mary Rowe’s on Acre Lot 49 in 1900, R. P. Dammond’s in Block 180 in 1902 and Harold Scott’s on Acre Lot 35 in 1903. In 1904 they built a house on their own ranch which the Evening Tribune described as both substantial and artistic looking, being built largely of stone. This house is also still standing, at 4775 Lamont, although it is set back from the street and nearly hidden by surrounding structures.

The Roxburghs did not live in their new home for long either; in 1906 they sold their portion of Acre Lot 50 to M. F. Chesnut, a real estate investor, who sold it the following year to Folsom Bros. Co. At the time Folsom Bros. owned most of the property in Pacific Beach and was engaged in improvement projects, particularly grading streets and pouring concrete sidewalks, which they hoped would attract purchasers and increase the value of their holdings. In 1912 the property was purchased by Alfred Hatch Brown, who also extended his ranch with a strip of land 125 by 250 feet just across Chalcedony Street in Acre Lot 33. Mr. Brown and his wife St. Claire Brown lived in the stone ranch house until they moved downtown in 1918, after which they rented out the house and land. The lemon boom had faded years earlier but this irrigated ranch land was ideal for vegetables and the tenants were mostly truck farmers, some of them Japanese immigrants. Arthur Yamaguchi occupied the house in 1920 and Yatoro Yamaguchi and his family lived there between 1929 to 1931, paying $40 a month rent. The Y. Yamaguchis and their American-born children were still living in Pacific Beach in 1942 and were among those sent to the Poston relocation center for ‘enemy aliens’ in Arizona during World War II.

The south half of Acre Lot 50 had been sold in 1901 to R. M. Baker, who had also acquired two other lemon ranches and a half-interest in the main lemon packing plant on the Pacific Beach and La Jolla railway line at the corner of Hornblend and Morrell streets. However, he also didn’t hold that property for long and in July 1902 sold it to Peter and Mary Vessels. In May 1908 the San Diego Union reported that Mrs. Vessels attended a city council meeting and spent half an hour asserting her rights over the removal of a hedge fence which stood in the way of the grading of Lamont Street being carried out by Folsom Bros. Co. According to the San Diego Union she told the councilmen that she would position herself on the fence and the only way they could get her off would be to push her off and plow her under. After a ‘spicy encounter’ between the fence owner and the vice-president of Folsom Bros. and a ‘long and tiresome debate with Mrs. Vessels in the lead’, the council passed a resolution directing the city engineer to enforce the grading of Lamont Street to the full width thereof including the sidewalks (and presumably any hedge fences that encroached on it). Lamont Street was graded, apparently without injury to Mrs. Vessels, and in October 1909 cement sidewalks were laid along Lamont, including a section in front of the Vessels property between Diamond and Missouri streets that still exists today .

In 1911 the Vessels began selling off portions of their property in the south half of Acre Lot 50, first the southeastern quarter and then the northeastern corner. Unlike most other acre lots in Pacific Beach, Acre Lot 50 was not re-subdivided into blocks and lots and these transfers were described as the easterly 275 feet of the southerly 135 feet and the easterly 100 feet of the northerly 135 feet of the southerly 270 feet of Acre Lot 50 (most property within Acre Lot 50 is still described in this manner). In 1916 the Vessels granted the city a strip of land 52 feet wide at the northern edge of their property, intended as a continuation of Missouri Street. The city did not receive a corresponding grant from the owner of the north half of the lot and as a result the continuation of Missouri Street today is not aligned with the street to the west and is much narrower (also, unlike most Pacific Beach blocks, there is no alley in the south half of Acre Lot 50). In 1917 the Vessels sold the southwestern 200 feet along Diamond Street and the northwestern 455 feet along Missouri Street, about three-quarters of their property, to Jesse and Lena Pritchard, leaving the Vessels with a 105-foot lot on Diamond which went to their daughter Blanche Vessels Lane. The house originally built for the Coffeens was included in the southwestern 200 feet of the lot but the Pritchards did not live in it. Instead it was rented, including, in 1919, to Yataro Yamaguchi, the Japanese truck farmer who later moved into the Roxburgh house.

In 1920 the southwest corner of the acre lot, including the Coffeen ranch house, was sold to George and Mary Churchman, who took up residence there and remained for over fifty years. George Churchman was a San Diego police officer who began with the bicycle detail and advanced to be head of substations in Ocean Beach and La Jolla and for a time during the prohibition era was in charge of the police vice squad. In one sensational 1921 incident (‘Bluecoat shoots 2 in dark store’), Patrolman Churchman shot a pair of burglars, killing one, after being struck in the head by a tire iron and threatened by a shotgun, which fortunately wasn’t loaded. While trying to ‘dry up’ the Sunset Supper Club while in charge of the Ocean Beach substation in 1925 Sergeant Churchman found a 23-year-old woman sitting on a bottle of gin and a 26-year-old woman with a bottle of gin ‘parked’ between her feet. A 26-year-old man approached, showed him a roll of bills, and offered him $50 to ‘forget about it’. All three were placed under arrest.

In April 1929 Churchman was elevated from sergeant to lieutenant and put in charge of the vice detail. A few months later, in August, the ‘dry squad’ led by Lt. Churchman raided a storeroom downtown and seized 4500 quarts of whisky, gin and other liquors worth $27,000. The illicit beverages had apparently been brought in for an American Legion state convention and there was a widespread belief that the Legion’s ‘irrigation committee’ thought that the police had been ‘fixed’. At the trial a witness testified that ‘someone got sore at the Legion’ and gave a tip to Churchman; if the tip had gone to the mayor or the chief of police the raid would never have happened. Churchman also led a raid that uncovered an illicit 200-gallon still and two 800-gallon mash vats in a house in Loma Portal.

However, in 1931 the vice squad came under attack by the bar association after a woman was arrested and held in jail over the weekend without being permitted to post bail. The San Diego Union reported that Lt. George Churchman, head of the vice squad, had determined that she was a ‘woman of a disreputable character’ and deemed it wise to hold her without bail until he could check up on her story (she was eventually charged with vagrancy but the charge was dismissed). The bar association threatened damage suits against the vice squad members, including Churchman, involved in what it called illegal arrests. Two members of the city council joined in denouncing the police department and demanded a general vice cleanup. The police chief resigned, claiming that his job had been made impossible by political interference, and Churchman was reassigned to head the La Jolla substation. After he also resigned from the police department he continued to be involved in security work, including the security of Camp Callan, on Torrey Pines Mesa, during the war years. He also continued to live in Acre Lot 50 until the early 1970s when he moved a block down the street to the new Plaza apartments.

By the mid-1930s the south half of Acre Lot 50 had been divided into a number of separate parcels and there were 5 residences existing along Diamond, Lamont and Missouri streets. However, the northern half had remained intact with the Roxburgh ranch house as the only residence. In 1937 the northern 125 feet, including the house, was sold to a construction company, but no additional homes were built until the 1940s. In 1940 Consolidated Aircraft began production of its B-24 Liberator bomber and hired tens of thousands of workers for its factories around the San Diego airport, creating a demand for housing in nearby areas like Pacific Beach. In 1941 the federal government built over 1000 temporary homes in the Bayview housing project just a few blocks east of Acre Lot 50 and commercial developers also began building affordable homes in the area for the new workers. There were still only 9 homes in Acre Lot 50 in 1941, 4 on Diamond, 2 on Lamont and 3 on Missouri but 6 more were built by 1945. By 1950 there were 20 homes, 9 on Diamond, 5 on Lamont and 6 on Missouri, but still none on the south side of Chalcedony Street. In 1950 Pacific Beach contractor Stanley Picard acquired this property, the northern 125 feet of Acre Lot 50 except for the 75-by-130 foot space around the Roxburgh ranch house, and in 1950 this parcel was subdivided as Picard Terrace. By 1955 eight homes had been built along Chalcedony Street in Picard Terrace and more than 20 addresses were listed in the 1900 block of Missouri. Like most of the rest of Pacific Beach, Acre Lot 50 was fully built out before 1960 and since then many of the first generation of single-family residences have been converted to multi-unit apartments and condos, but Acre Lot 50 has the distinction of having preserved not one but two of its original lemon ranch houses, even if they are well hidden.