The San Diego Union-Tribune recently published a Life Tribute for Franklin Lockwood ‘Woody’ Barnes, who had passed away in July 2021 at the age of 86. The tribute noted that Woody was born in San Diego but had lived most of his life in Julian, attending the Julian elementary and high schools. His family had operated an apple and pear orchard in Julian since 1906 and had built the Manzanita Ranch store in Wynola. He was very active in the agricultural life of Julian and believed that he was the only one who remembered most of that earlier era. He shared these memories in a 2020 book Woody Barnes – A Farmer’s Life in Julian, compiled by his son Scott.

Woody’s memories of earlier eras and the agricultural life also extended to another local community where his forebears had attended school, operated orchards, and had a store. In fact, his great-grandmother claimed to be the very first resident of that community — Pacific Beach – when she came to help start a new college that opened there in 1888. One great-grandfather was among its first lemon ranchers and owned the lemon packing plant at a time when lemons were the community’s main product. Another great-grandfather was a contractor who built many of the first homes there, including his own.

These pioneers came to Pacific Beach in part so that their children, Woody’s grandparents, could attend the new college. The college closed after a few years, but those former students married and started their own family in Pacific Beach, where Woody’s father was born and his grandfather became the community’s grocer and postmaster. Their days in Pacific Beach were limited, however, and by 1906 the family had relocated to uptown San Diego. Some, including Woody’s father, later moved on to Julian where Woody and his sister Jo grew up.

Although their family had left over a century earlier Woody and Jo were very conscious of their Pacific Beach roots. Both became members of the Pacific Beach Historical Society and have shared family photos and other memorabilia from those days that have enhanced our knowledge of PB’s early history, and their family’s prominent role in it.

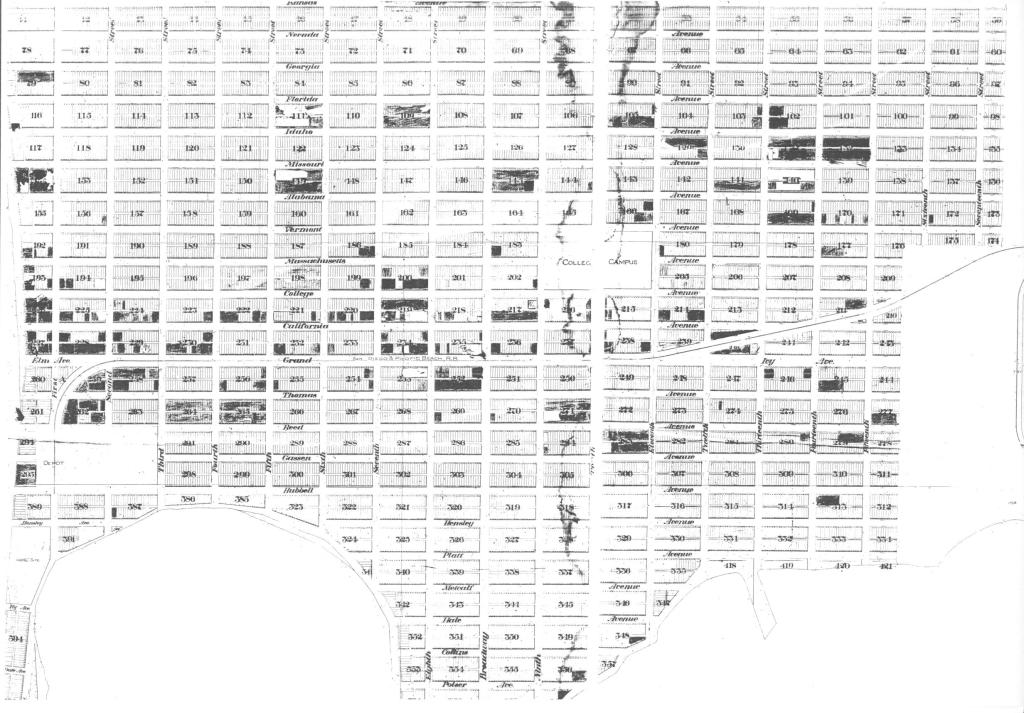

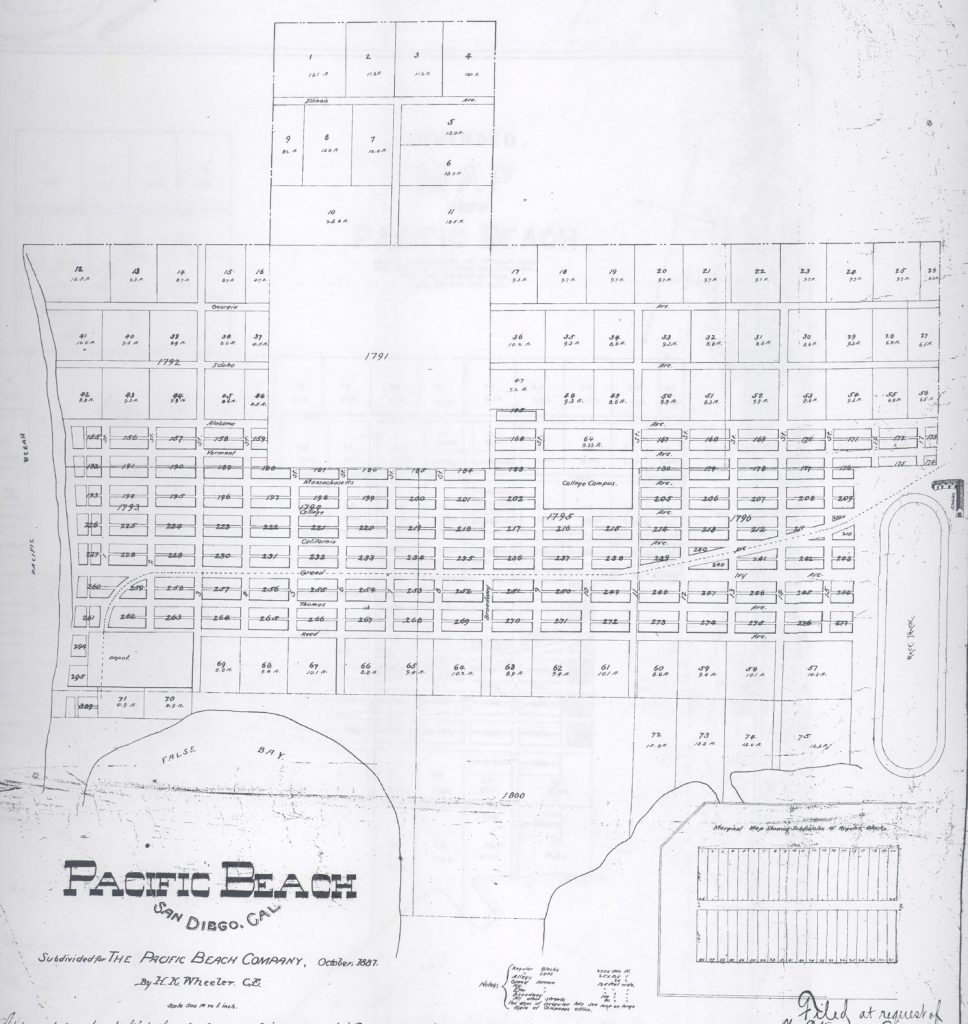

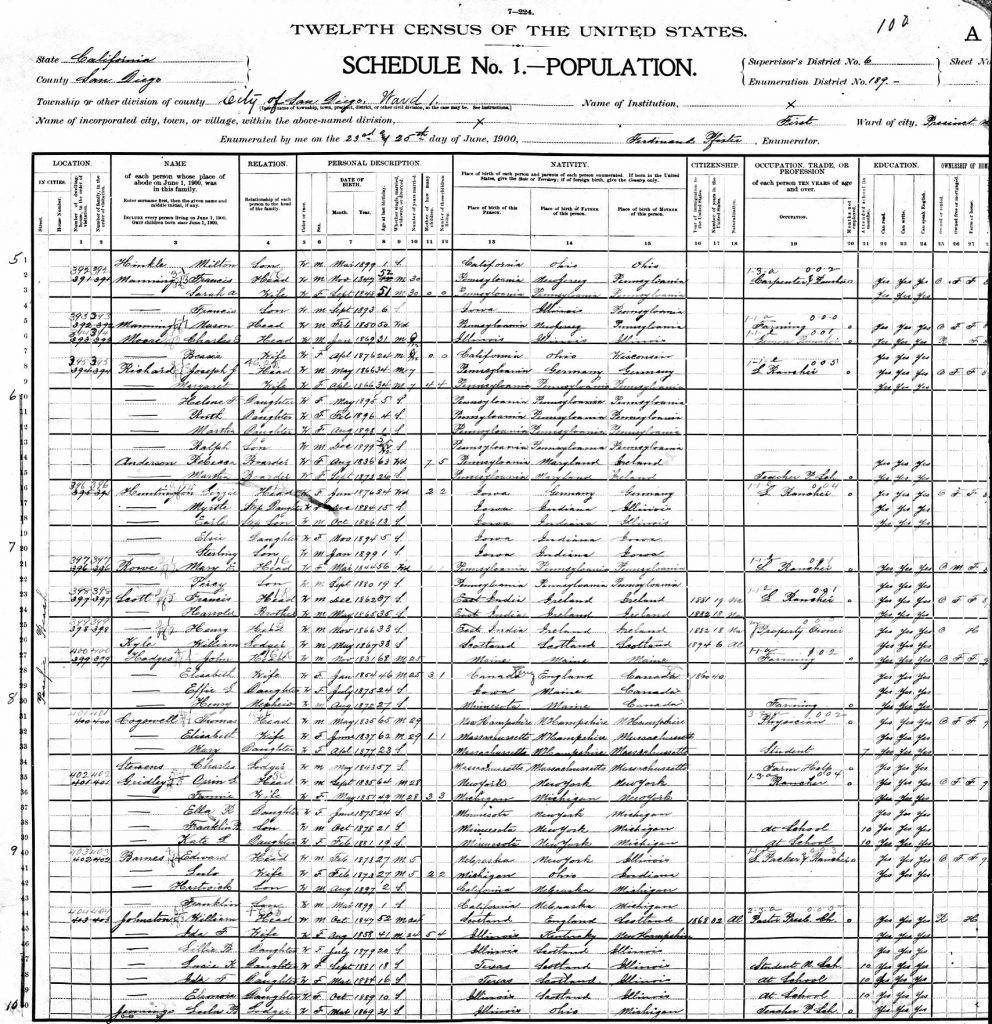

Pacific Beach began in 1887 when a group of San Diego businessmen bought most of the land north of Mission Bay (then known as False Bay), drew up a subdivision map, and began selling lots. Their plan was to attract residents by making it the site of San Diego’s first college. The San Diego College of Letters opened in 1888 on a campus where the Pacific Plaza shopping center is now located. There were 37 students in the inaugural class, 15 young ladies and 22 young men, including Woody and Jo’s grandparents Lulo Thorpe and Edward Barnes.

Lulo’s mother, Rose Hartwick Thorpe, was a poet, perhaps the most popular poet of her day, world-famous for the ballad Curfew Must Not Ring Tonight which she had written at the age of 16. The Thorpes had been living in Texas when the promoters of the college invited Mrs. Thorpe to come to Pacific Beach to assist with its creation. Lulo’s father, Edmund Carson (E. C.) Thorpe, had been a carriage maker but in San Diego he joined the real estate boom then underway by becoming a provider of small portable cottages, put together with removable pins rather than nails. Mrs. Thorpe later claimed they became the very first settlers in Pacific Beach when they set up their own portable house on a lot near where the college was being built.

Edward Young (E. Y.) Barnes had come from Nebraska, where his father Franklin Wile (F. W.) Barnes had been a banker before moving to California for his health. They settled in Pacific Beach where Edward and his brother Theodore enrolled in the college. The Barnes family was among the first to build a house in Pacific Beach, at the northwest corner of what are now Lamont and Emerald streets, just across Emerald from the college campus.

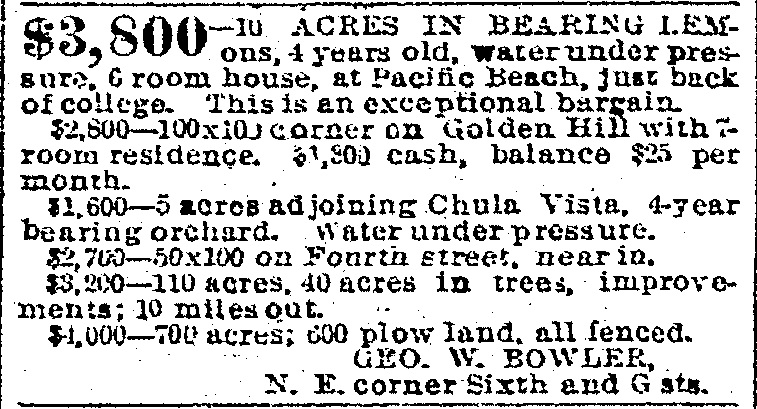

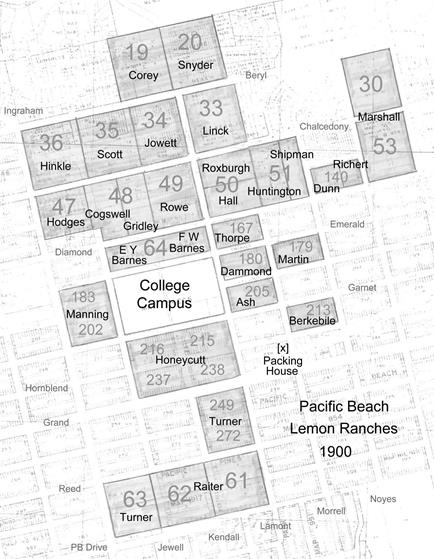

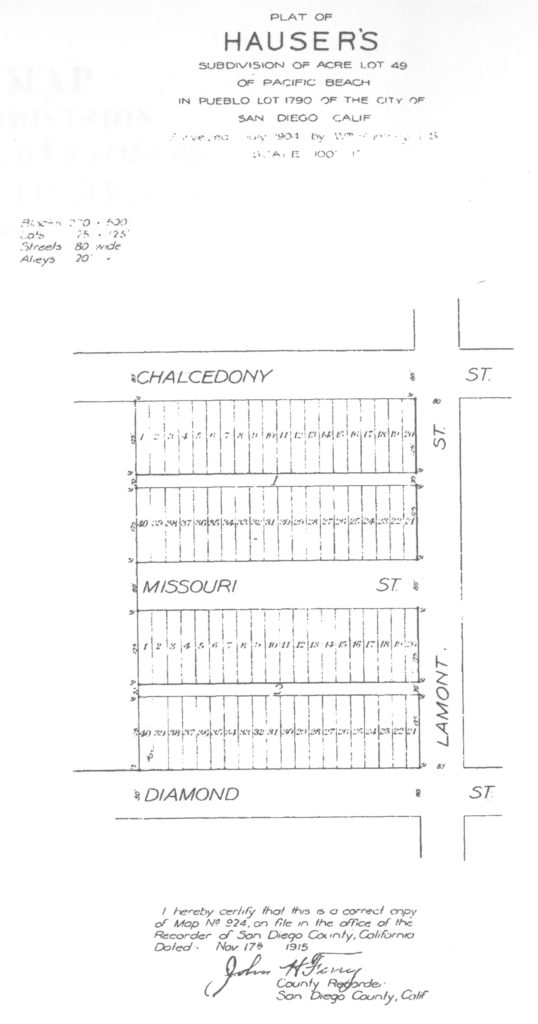

Pacific Beach, and the college, had been founded during San Diego’s ‘great boom’ when rapid population growth fueled an apparently limitless demand for residential real estate. The developers of Pacific Beach endowed the college with hundreds of building lots with the expectation that they could be sold to fund its operations, but the great boom collapsed in 1888 and despite several auctions complete with a free barbecue lunch few lots were sold and the college closed in 1891. Most of the academic community departed but the Thorpe and Barnes families remained and found that their property on the ‘sunny slope’ in the vicinity of the college campus was ideal for lemon cultivation. The developers of Pacific Beach encouraged this new industry by re-subdividing much of the area into ‘acre lots’ of about 10 acres which were sold to potential lemon ranchers.

The Barnes’ property was included in one of these acre lots, 9.32 acres surrounded by Emerald, Jewell, Diamond and Lamont streets, on which F. W. Barnes planted 600 lemon trees. By 1897 these trees were yielding 1400 boxes of lemons annually (a box contained about 40 lemons and sold for about one dollar). The Thorpes did not get an entire acre lot but did buy the city block across Lamont from the Barnes on which they planted lemons and other fruit trees, and in 1894 E. C. Thorpe built a house there that they named Rosemere Cottage in honor of Mrs. Thorpe. In 1895 E. Y. Barnes built a house at the southwestern corner of his father’s acre lot, the northeast corner of Emerald and Jewell, and named it El Nido, or the nest.

In July of that year the San Diego Union reported that the most interesting event at Pacific Beach was the marriage of Miss Lulo Thorpe and Edward Y. Barnes, impressively performed at the home of the bride’s parents. According to the Union a lovelier bride could hardly be imagined, and the happy couple were then escorted to their handsome home El Nido, recently built by the groom, which was but one block from both of their parents. A year later the western half of F. W. Barnes’ acre lot, including El Nido and several hundred lemon trees, was transferred to Edward Y. and Lulo Barnes.

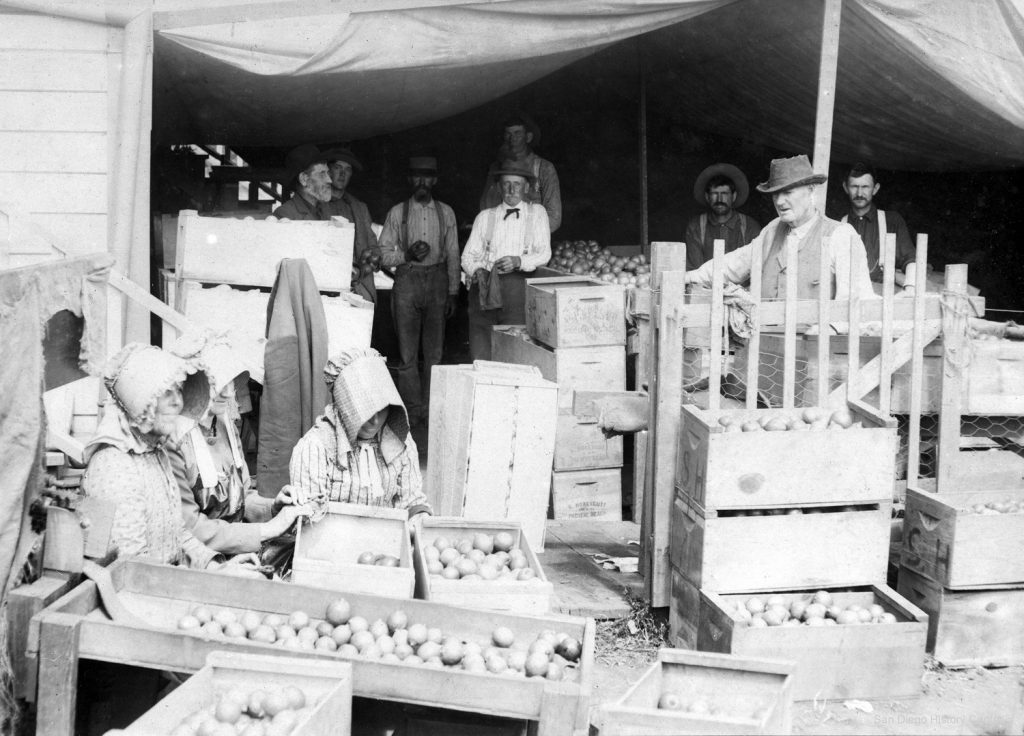

The Barnes not only grew lemons on their ranch but were also responsible for handling and shipping much of the local lemon crop. In 1897 a large building which had been built as a dance pavilion at the beach was moved to the corner of Hornblend and Morrell streets, adjacent to the railroad line that ran between San Diego and La Jolla over Balboa Avenue. The building was converted into a lemon curing and packing plant and the railroad company put in a new siding to allow fruit to be shipped directly from its rear doors. Later in the year F. W. Barnes and another rancher purchased the plant and E. Y. Barnes was put in charge of its operation. In December 1897 the Union reported that Barnes & Son had the most commodious packing and curing house in the county and were shipping between 75 and 100 boxes of lemons weekly.

F. W. Barnes was also an enthusiastic promoter of the local lemon business, describing Pacific Beach in an 1898 Union article as the natural home of the lemon, one of the few localities in the whole country where conditions were almost perfect for its successful culture. When the county horticultural society held its quarterly convention that year in Pacific Beach the stage was decorated with ‘festoons’ of lemons and F. W. Barnes gave the featured address on ‘How We Handle Our Lemons’. He was nominated for president of the society for the coming year and declared elected.

F. W. Barnes had also been elected to the San Diego Board of Delegates (a predecessor of San Diego’s city council) in 1897 and in 1900 he was the winning candidate for the 79th State Assembly district, representing the city of San Diego in Sacramento. With the added responsibilities of political office he divested his business interests in Pacific Beach, selling his share of the lemon packing plant in 1901. In 1904 he and Phoebe left Pacific Beach altogether, selling their home and lemon ranch and building a new home at 4th and Upas streets in the uptown area. After three terms as an assemblyman he resigned and was appointed Collector of Customs for the Port of San Diego by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1905.

The Thorpes owned the city block between Diamond, Morrell, Emerald and Lamont streets in Pacific Beach, directly across Lamont from the Barnes’s ten-acre ranch. Although there were lemon trees on the property lemon ranching was not their primary occupation. The 1900 census listed E. C. Thorpe as ‘Contractor and Rancher’ and he had become one of the principal home builders in Pacific Beach and La Jolla. One home he built in 1896 was for the Gridley ranch, just across Diamond Street from the Barnes ranch and about a block from his own property. In an 1896 diary passed down to her great-grandchildren Mrs. Thorpe wrote that her husband ‘Ned’ had secured the contract and started building Mrs. Gridley’s house on January 13. There were rainy days when Ned couldn’t work but on March 11 she noted that house was finished and Ned had gone to San Diego to pay the bills. The Union’s Pacific Beach Notes confirmed on March 15, 1896, that Mrs. Gridley was moving into her new house. The Gridley house stood until 1968 at 1790 Diamond Street (next door to the house I grew up in).

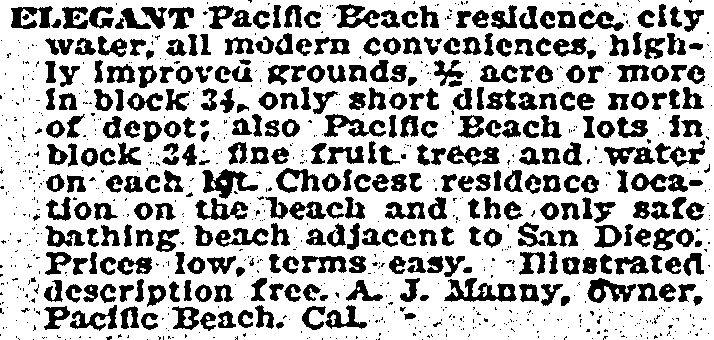

The Thorpes had also listed their own home for sale in 1896; Mrs. Thorpe’s diary entry for January 8 noted that the advertisement had appeared in the paper for several days. That day’s Union did include an ad for a home, ‘substantial and beautiful, for I built it for myself’, consisting of a 7-room house and the finest, best located 5-acre tract of lemons in the city. However, the house was not sold and the Thorpes remained there for several more years.

Rose Hartwick Thorpe continued to publish poems in literary magazines and to hold ‘recitations’ of her work. One poem, Mission Bay (‘now blue, now gray’), is often cited as the origin of the current name for what was then False Bay. Her husband often joined her performances, assuming the character of ‘Hans’ and affecting the ‘broken English of a Dutchman’ to recite his own poems such as ‘Dot Bacific Peach Flea’ (‘Vot schumps und viggles und bites . . . Und keepen me avake effry nights’). In 1896 the couple went on a six-month tour giving ‘entertainments’ in churches and other meeting halls around the country. Rose Hartwick Thorpe, Phoebe and Lulo Barnes and other local women started the Pacific Beach Reading Club in 1895 and Mrs. Thorpe was elected its first president. Before a clubhouse was built in 1911 meetings were held in members’ homes, often those of the Thorpe and Barnes families. The club, now known as the Pacific Beach Woman’s Club, is still active and its logo, a lemon branch, pays tribute to its lemon-ranching founders.

By 1901 most of Mr. Thorpe’s business was in La Jolla and the Thorpes purchased lots on Girard Avenue and built another home there, Curfew Cottage. In 1902 they transferred Rosemere Cottage and their block of land in Pacific Beach to their daughter Lulo and son-in-law Edward (E. Y.) Barnes. The Barnes and their three children, Hartwick Mitchell (1897), Franklin Lockwood (Woody and Jo’s father, born in 1899) and Margaret (1901), moved the two blocks from El Nido to Rosemere.

E. Y. Barnes had managed operations at the curing and packing plant for several years after its conversion in 1897, shipping carloads of lemons east. When his father sold his interest in the plant in 1901 it closed briefly but at the end of 1901 Barnes & Son rented and reopened it and were soon shipping more carloads to eastern destinations. Later that year E. Y. diversified his business interests by taking over the community’s general store at the northwest corner of Grand Avenue and Lamont Street, and in 1904 he sold the lemon ranch and exited the lemon business entirely. The San Diego Union reported that he would greatly enlarge his store and give his entire attention to it. The Barnes store also served as the community’s post office and E. Y. Barnes became postmaster. In addition, the polling place for municipal elections was Ed Barnes’ store and he was the inspector.

There were less than 200 people living in Pacific Beach at the turn of the twentieth century and their activities, particularly the activities of the prominent and popular Barnes and Thorpe families, were noted in weekly Pacific Beach Notes columns in the local papers. Some of the photos passed down from those days appear to illustrate items that also appeared in these columns. One family photo showed Mr. and Mrs. Thorpe and their daughter Lulo and her three children seated in a vintage automobile (with two other children standing in the back).

Automobiles were making their first appearances in the early years of the century and the Union found it newsworthy to report in July 1903 that Assemblyman F. W. Barnes and E. C. Thorpe, of Pacific Beach, had each purchased a handsome French-make automobile in Los Angeles and rode down in them to their homes, covering the 125 miles in comparatively short time and without mishap. These latest arrivals brought the total number of cars in San Diego to 19. The Union later clarified that the two vehicles were actually Cadillacs and that in view of the popularity of these machines the San Diego Cycle and Arms company had secured the agency for them so that it would no longer be necessary to purchase them in Los Angeles. They cost only $950, were able to make almost any road or hill with perfect ease and could attain a speed of forty miles an hour (the car in the photo was indeed a 1903 Cadillac runabout, the very first Cadillac model, with a single cylinder engine and chain drive). In another photo Mr. Thorpe is apparently making repairs, probably to the chain, while Mrs. Thorpe holds an umbrella.

Although it was said these early Cadillacs could attain a speed of 40 MPH there were few improved roads in the vicinity where such a speed would actually be attainable. Pacific Beach provided an alternative, a hard, flat, miles-long beach which at low tide was hundreds of feet wide, and a September 1903 Pacific Beach Notes column reported that F. W. Barnes and E. C. Thorpe had ‘raced’ their automobiles on the beach. They made the entire length in eight minutes, about 30 miles per hour over the nearly 4-mile distance (in 1912 ‘Wild Bob’ Burman covered a mile course on the same beach in 28 seconds, nearly 130 MPH).

The Evening Tribune reported (in a ‘Newsy Letter from Pacific Beach’ in July 1903) that Mr. E. Y. Barnes had also ordered an automobile from the east, but apparently it hadn’t arrived when another of the Barnes family photos was taken, showing him and his children in a carriage on Emerald Street in front of Rosemere Cottage.

The Barnes and Thorpes may have been responsible for introducing automobiles to Pacific Beach, but cars were not necessarily welcomed there at the time. One Tribune dispatch from Pacific Beach in 1903 noted that the horses didn’t seem to fancy them. Another said that people had given up pleasure driving (i.e., horse and carriage) for fear of the automobile.

Another century-old family photo captured of a group of children around a May pole in what appears to be the Barnes’ front yard, between Rosemere Cottage and Emerald Street. Although the photo is undated, the San Diego Union’s Pacific Beach Notes column reported on May 4, 1906, that Hartwick Barnes, the little son of Mr. and Mrs. E. Y. Barnes, had entertained sixteen friends with a party, the greatest enjoyment being found in weaving the many colored ribbons into a perfect braid around a May pole, singing appropriate songs while skipping and dancing in and out (the ‘artistic’ pole was then used to test the agility of the boys in climbing). The Union article included the names of those present, who in addition to the Barnes children were from the Hinkle, Richert, Dula, Scripps, Corey and other pioneer Pacific Beach families.

Hartwick Barnes’ May Day party turned out to be one of the Barnes family’s last appearances in Pacific Beach. In September 1906 the Union reported that Mr. and Mrs. E. Y. Barnes and family had moved into San Diego to superintend the building of their new home there. The new home was just across Upas Street from his parents’ home, at the southeast corner of 4th and Upas, and the Barnes children continued to celebrate May Day there. After relinquishing his retail produce business in Pacific Beach E. Y. Barnes joined Jarvis Doyle to form the Doyle-Barnes wholesale produce company at 326-336 5th Avenue, a warehouse that is now Cerveza Jack’s Gaslamp. He also leased and later bought property in the Pine Hills area of Julian where his son Franklin moved in 1922 and where Franklin’s children Woody and Jo grew up. The home at 4th and Upas streets is still there, although extensively remodeled, and the family still owns Manzanita Ranch, the property in Pine Hills.

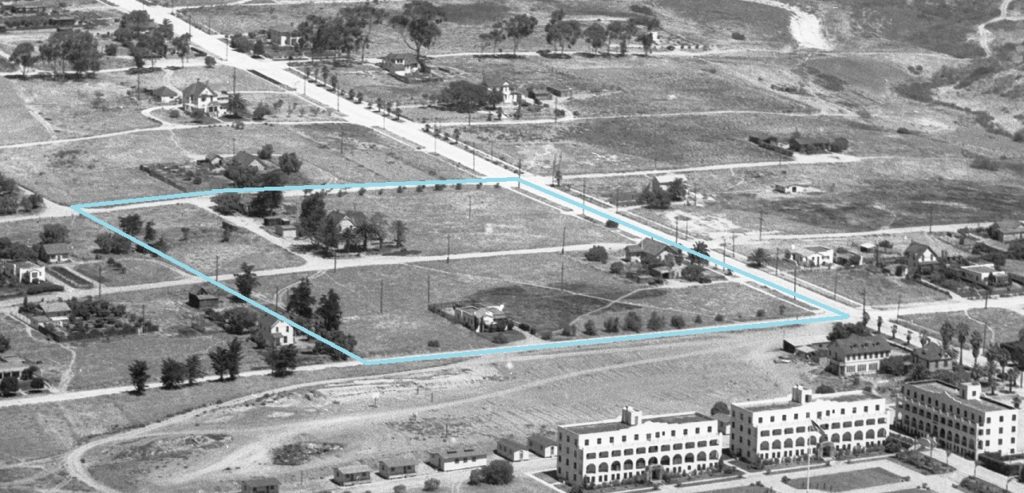

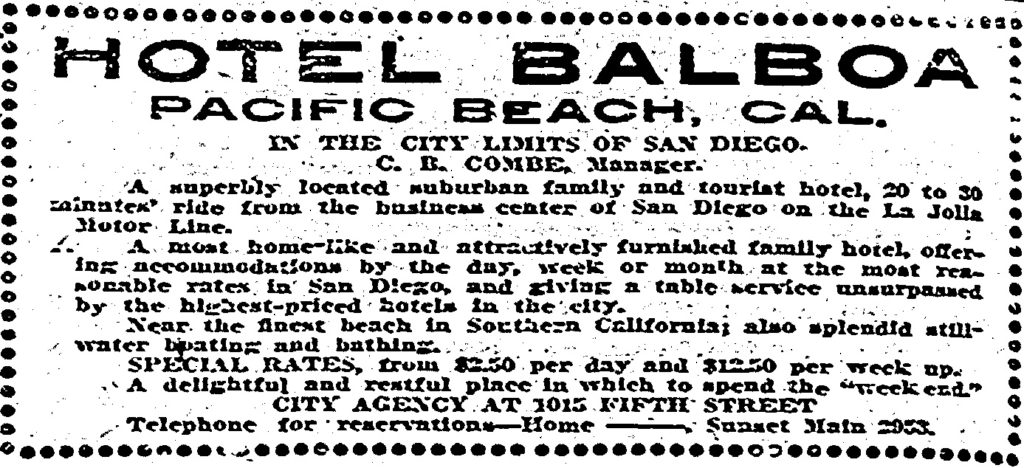

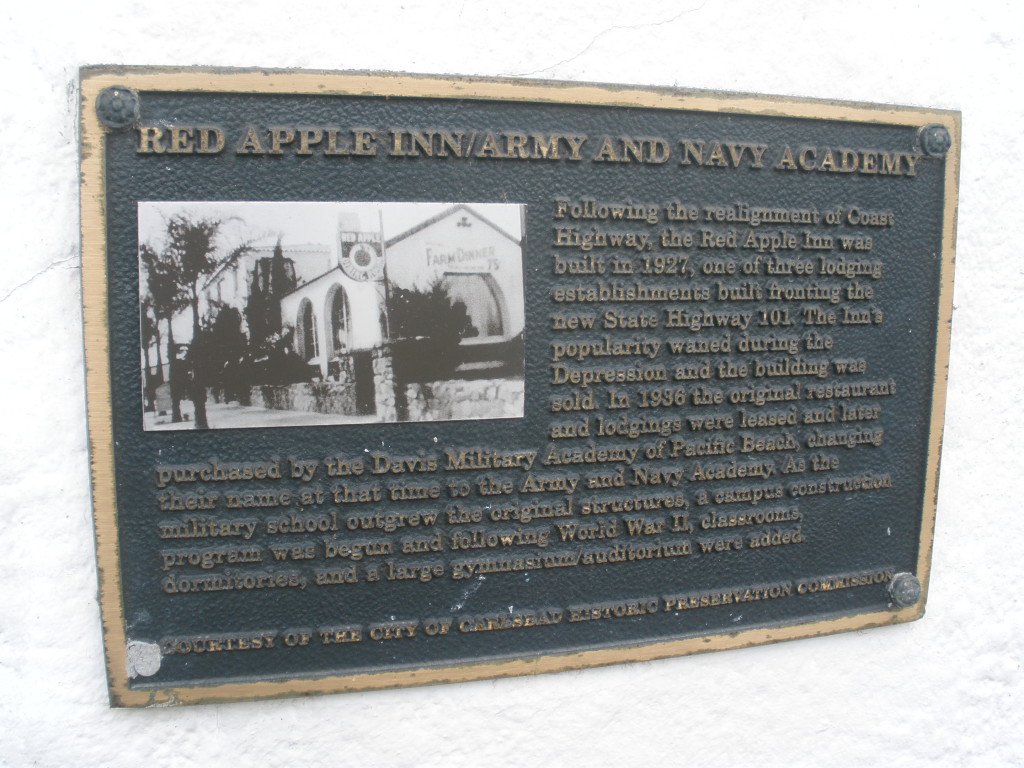

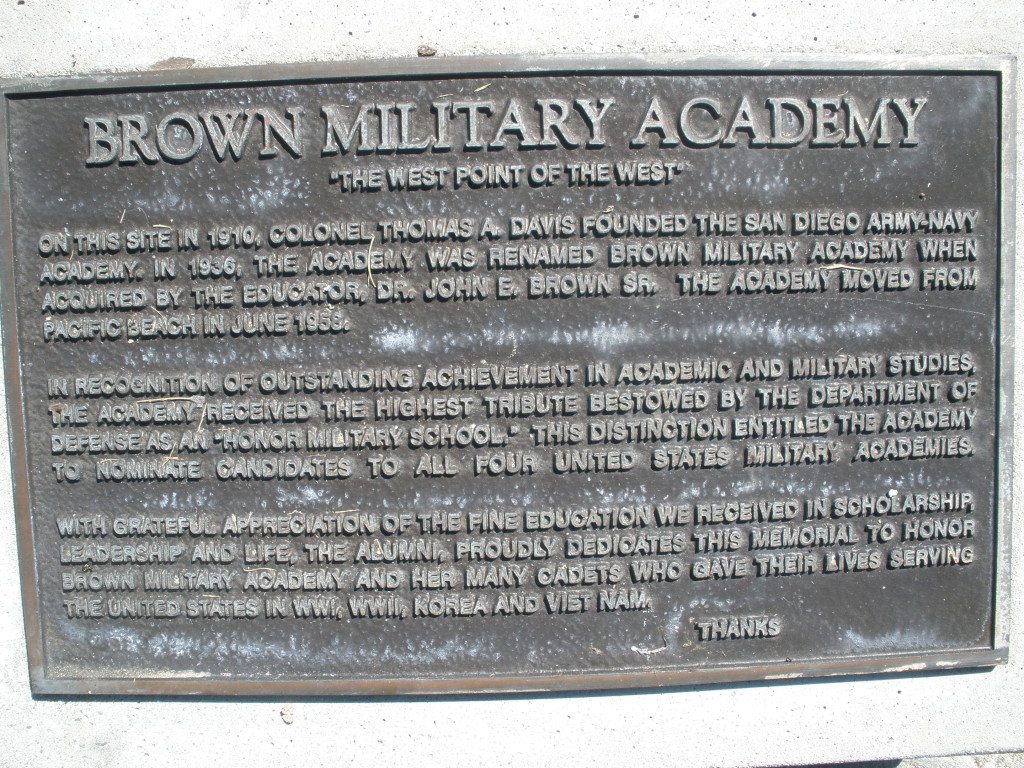

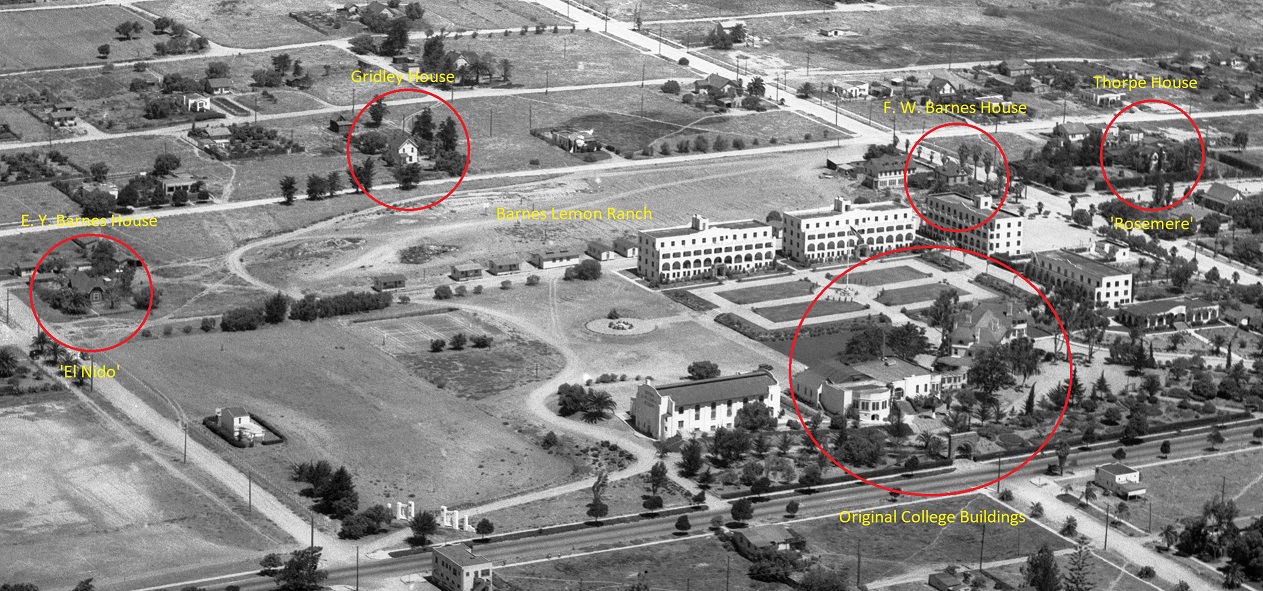

Back in Pacific Beach, few of the landmarks seen in the Barnes photos are still in existence. The college which had originally attracted the families to the area and where E. Y. and Lulo Barnes had been students closed in 1891. In 1905 it was refurbished and reopened as a resort hotel, the Hotel Balboa. The hotel was also unsuccessful but in 1910 Thomas A. Davis acquired it and founded the San Diego Army and Navy Academy, later Brown Military Academy. In 1923 Davis expanded the academy campus by purchasing what had once been the Barnes lemon ranch on the other side of Emerald Street. The Barnes families’ former homes became residences for academy staff. Col. Davis’ brother, the academy commandant, also purchased the Thorpes’ former home at Lamont and Emerald in 1924 and the Davises’ mother lived there until 1954. That house burned down in 1957 and is now the site of the Lamont Emerald apartments. Two years later the academy itself relocated to a new campus in Glendora and the original college buildings and the former Barnes homes were demolished. The site of F. W. and Phoebe Barnes’ home is now a parking structure for the Plaza condominium complex and E. Y. and Lulo Barnes’ home, El Nido, is an employee parking lot for the Pacific Plaza shopping center.

Other landmarks associated with the Barnes are also gone. The former dance pavilion moved to Hornblend and Morrell streets and converted to a lemon packing plant, owned by F. W. Barnes and operated by E. Y. Barnes, underwent one more conversion in 1907, this time into a Methodist church. The church operated there until 1922 and the site was then cleared and is now covered with houses and apartments. Ed Barnes’ store and post office at Grand and Lamont was taken over by Clarence Pratt when the Barnes left Pacific Beach. In the mid-1920s Pratt opened a new store and post office two blocks north on Garnet Avenue and the former Barnes store was abandoned. The site of Ed Barnes’ store is now a strip mall.