When Pacific Beach was founded in 1887 its founders recognized that development of their new suburb would depend on reliable transportation to and from downtown San Diego. They formed the San Diego and Pacific Beach Railway Company and received a franchise from the San Diego city council granting them a right of way around the northeast corner of Mission Bay (then called False Bay) from a ‘point on the Pacific Ocean Beach’ to Old Town. At Old Town it would connect with the San Diego & Old Town Street Railroad, which began service between Old Town and a depot at the corner of Broadway and Kettner Boulevard (then D and Arctic streets) in October 1887. These two railroads would be consolidated to form the San Diego, Old Town & Pacific Beach Railway in April 1888.

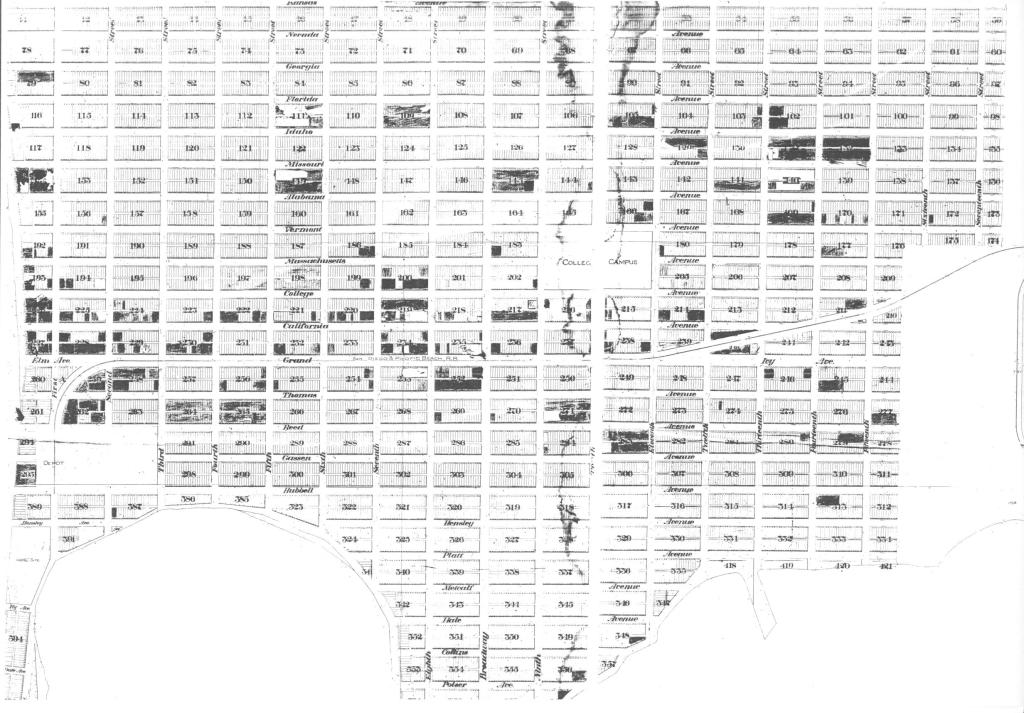

The railway’s route in Pacific Beach was laid out in the original Pacific Beach subdivision map of October 1887, which shows the right of way following Grand Avenue from a depot near the beach to what is now Mission Bay Drive at the far eastern side of the community, where it turned south toward Old Town. Grand Avenue was made wider than other streets in Pacific Beach, 125 feet rather than 80 feet, to accommodate the railroad (the diagonal section of Grand Avenue on the 1887 map east of Eleventh Street, now Lamont, has since been reclassified as extensions of Balboa and Garnet avenues and Grand extended east of Lamont over what was then Ivy Avenue). The route over Balboa and Garnet avenues was necessary at the time to circumvent the Pacific Beach Driving Park, an oval racetrack with a one-mile course, which was also being built in 1887 north of Mission Bay and east of Rose Creek.

Construction of the Pacific Beach railroad began at Morena in December 1887 and progressed north and west around the racetrack as far as Lamont Street by January 1888. At Morena a temporary interchange was built to connect with the California Southern Railroad, a subsidiary of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway that ran along the east side of Mission Bay linking San Diego to its transcontinental railway system. The interchange allowed trains to run over the California Southern tracks from its station downtown, switch over to the newly laid Pacific Beach railroad track at Morena and continue on to Lamont and Grand. On January 28, 1888, two trains brought an estimated 2500 spectators there to celebrate the laying of the cornerstone for the first building constructed in Pacific Beach, the San Diego College of Letters at Lamont and Garnet (then College) Avenue, where Pacific Plaza is located today.

Over the next few months the rails were extended west on Grand to a depot at the beach and south from Morena toward Old Town parallel to and west of the California Southern tracks, crossing the San Diego River over a newly built bridge. South of the river the Pacific Beach line passed to the east side of the California Southern tracks over a grade crossing and continued into Old Town, where it joined the existing line that connected Old Town to the San Diego depot at Broadway and Kettner. Through trains began running between the railroad’s San Diego and Pacific Beach depots on April 29, 1888.

The Old Town railroad had begun service in 1887 with a new steam ‘dummy’ locomotive, which became the San Diego, Old Town and Pacific Beach Railway No. 1 when the two railroads were consolidated in 1888 (dummy locomotives had an outer housing that hid much of their running gear so as not to frighten people and horses on street railways). This locomotive was joined by a pair of larger 24-ton dummies from the Baldwin Locomotive Works (Nos. 2 and 3) and passenger coaches ‘elegantly finished in hard woods’ before the railroad began service to and from Pacific Beach. Most of the trains were short, just a combination passenger/express car and a passenger coach or two in addition to the engine. Initially there were six round trips daily, with the first train leaving Pacific Beach at 6 AM and the last train returning at 9 PM, although the time card promised that on Sundays trains would run from San Diego to Pacific Beach hourly from 8 AM to 6 PM. The round trip fare was 25 cents.

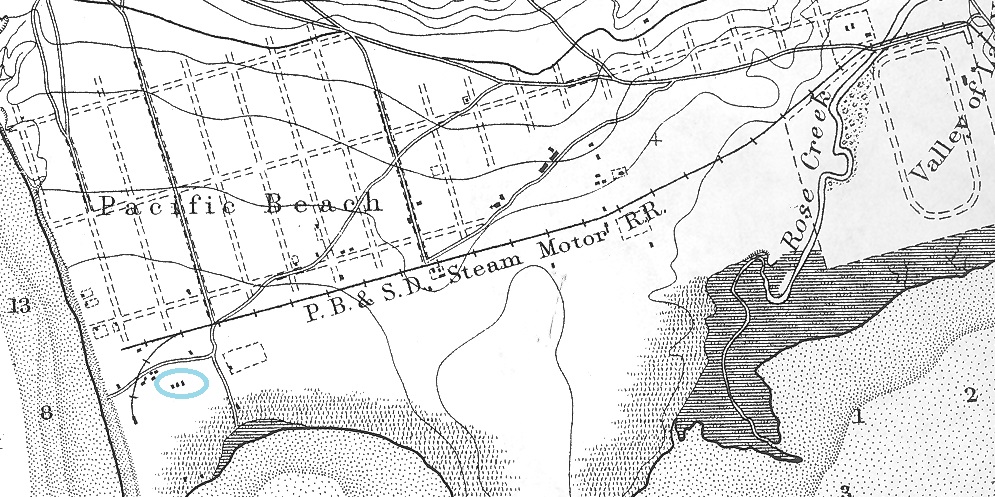

After departure from the downtown depot and stops at Old Town and Morena, the first stop in Pacific Beach was the driving park (racetrack), followed by stops for Rose Canyon and the asbestos works. The asbestos works, located about where Soledad Mountain Road intersects Garnet Avenue today, produced asbestos boiler coatings and asbestos paint and depended on the railroad for delivery of raw materials from a mine near Elsinore and for shipping finished goods, mostly to the port of San Diego. The asbestos works closed and the stop was removed from the railroad’s timetable in 1892.

The next stop was the college station at Lamont Street, serving the College of Letters two blocks to the north. The college was the principal cultural and economic activity in Pacific Beach from its opening in 1888 until it closed in 1891. Although many students and faculty lived on campus or elsewhere in Pacific Beach others commuted from San Diego, and the railroad also brought crowds from San Diego for ‘elocution contests’ and other activities and ceremonies at the college. When the second college building, Stough Hall, was opened in January 1890 a special train carried several carloads of people from the city. The San Diego Union reported that the college buildings were brilliantly lighted and the avenue from the cars to the buildings illuminated with rows of Chinese lanterns on either side.

Near today’s Bayard Street at the western end of Grand the tracks turned south into the depot grounds, which included an engine house where locomotives could be parked and maintained. The equipment and crews were based at the depot grounds where the trains began and ended their daily runs, and crew members and their families lived in a row of houses on Reed Avenue adjacent to the depot grounds. A hotel and pavilion were built overlooking the beach near the end of the line as an attraction for passengers. During the summer of 1888 the railroad promoted band concerts featuring the Red Hussar Band on Sundays at the pavilion, where sports including surf bathing could also be indulged in.

With two new Baldwin locomotives in service the general manager of the Pacific Beach railway claimed that the line could carry 20,000 passengers each day, but even on summer Sundays with the Red Hussar Band playing at the pavilion actual ridership was far less. The original schedule of six trains daily and hourly departures on Sundays was steadily cut back, to five trains daily and 8 on Sunday in September 1888, five daily and Sunday in May 1889, and four in October 1889. After August 1890 the timetable showed only three trains daily; the first train left Pacific Beach at 7:30 and the last train returned at 6. The round-trip fare was still 25¢.

The San Diego, Old Town & Pacific Beach Railway’s time cards also noted that a stage to La Jolla met the morning train and returned in time to connect with the evening train at Pacific Beach. However, La Jolla residents wanted a railroad connection of their own and in 1893 the railway’s owners obtained a franchise to extend the line from Pacific Beach to La Jolla. The extension ran from Grand Avenue in Pacific Beach north along what is now Mission Boulevard to about Wilbur Street, where it turned toward the northwest and followed a route that is now La Jolla Boulevard, La Jolla Hermosa Avenue and Electric Avenue in La Jolla. Between today’s Bonair Street and Sea Lane the right of way crossed residential blocks, then continued over Cuvier to Prospect Street. Construction began in March 1894 and was completed in May.

At a ceremony on May 15 attended by a large crowd that had ridden excursion trains from the city, Mrs. Emma Harris, a guest at the La Jolla hotel, was invited to drive the last spike ‘which lay glittering like pure gold on the last tie with a silver sledge nearby’. The San Diego Union reported that ‘contrary to tradition’ she did not miss the mark and drove the spike to its last resting place while the assembly cheered and the band played. A month after the last spike ceremony the line was extended another 1400 feet along Prospect Street where a shed was put up to serve as a depot.

The new San Diego, Pacific Beach & La Jolla Railway timetable continued to list three trains daily, including Sunday, with morning, mid-day and late-afternoon departures. Since the railroad’s light dummy engines were not well suited to the longer distance and running time and the steeper grades of the new route one of the Baldwin dummies, No. 2, was exchanged with the Coronado Railroad for a more capable ‘saddle tank’ locomotive that had once operated on the New York elevated railroad. The new locomotive was also given the number 2 and both the new No. 2 and No. 3, the line’s other Baldwin dummy, were re-lettered S.D., P.B. & L.J. Ry. Engine No. 1, the dummy inherited from the Old Town railway, was retired and kept in the engine house as a back-up.

In Pacific Beach the college had closed in 1891 and the community adapted by becoming a center of lemon cultivation. Most of the lemon ranches were located in the vicinity of the former college station at Lamont and Grand, which was also close to the community’s stores, churches and school. In 1898 the hotel and pavilion were also moved from their original locations near the foot of Grand Avenue to this central area. In its new location at the corner of Hornblend and Morrell streets the pavilion was adjacent to the railway line, which then ran on Balboa Avenue. The pavilion building was converted to a lemon packing facility which cured and shipped carloads of lemons from a siding connected to the railway line.

In 1899 the Pacific Beach and La Jolla railroad was sold to E. S. Babcock, who also owned the San Diego, Cuyamaca & Eastern Railway which served Lemon Grove, La Mesa, El Cajon and Lakeside from a depot at the foot of Tenth Street in San Diego (following the route of today’s Orange Line trolley). In 1904 Babcock began construction of an electric street railway to connect the San Diego depots of his two railroads. The line ran from the depot of the Pacific Beach and La Jolla line at the foot of C Street (it had been moved a block north from Broadway), along C and Sixth streets to L Street (where it passed the National City & Otay Railway’s downtown depot, now the 207 Bar at Hard Rock Hotel), then over what is now the ‘Gaslamp Diagonal’ to the Cuyamaca depot at Tenth and Commercial. When this line opened in 1905 electric streetcars met trains at each depot and traveled through the downtown area to the other depots, where trains would be held for the cars’ arrival. Passengers could also board the electric cars at central locations downtown and transfer to steam trains at the depots.

When the electric cars appeared on the C and Sixth street line they were lettered ‘Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railway’, and a notice appeared in the San Diego Union announcing the ‘Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railway – Electric cars along C and Sixth streets connect with all incoming and out-bound trains on the N.C. & O. Ry., S.D.C. & E. Ry and S.D., P.B. & L.J. Ry. Day or night’. In 1906 Babcock officially incorporated the Los Angeles and San Diego Beach Railway Company, stating its intention to build a railroad connecting Los Angeles and La Jolla and to acquire the San Diego, Old Town & Pacific Beach, the San Diego, Pacific Beach & La Jolla and the National City & Otay steam railroads to make a line stretching from Los Angeles to Tijuana. The new company did acquire the Pacific Beach and the La Jolla railroad companies (which had never actually been merged) and they were absorbed along with the C and Sixth street electric line. The Otay railroad was never acquired and the line was never extended north of La Jolla but from then on the railroad between San Diego and La Jolla via Pacific Beach was officially the Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railway, although it was generally known as the La Jolla line.

The new Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railway updated its schedule to add two round trips daily, beginning and ending at La Jolla where the rolling stock and trainmen were then based. Two round trips, one in the morning and the other the last run of the day, were mixed trains that carried freight in addition to passengers. The mixed trains included a passenger/express car and even freight cars in addition to a passenger coach, and their schedules overlapped with the passenger trains, making it necessary to operate a separate train with a second engine and crew. The passenger-only trains were scheduled for a 40-minute run between San Diego and La Jolla. On Sundays only the three passenger trains operated, as before. The new schedule also continued an extra ‘theater train’ on Saturday night, introduced in November 1903, which left La Jolla at 7:10 PM and returned from San Diego at 11:10 PM.

In addition to its new name and schedule, the Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railway also undertook an upgrade of its motive power in 1906. The Baldwin dummy which had been S.D., P.B. & L.J. Ry. No. 3 was rebuilt, with its dummy housing cut back into a cab; it became L.A. & S.D.B. Ry. No. 1. The other original Baldwin dummy, which had been traded to the Coronado Railroad in 1894 and rebuilt there as a tender engine, was reacquired and became L.A. & S.D.B. Ry. No. 2 (the saddle tank former New York Elevated engine it had been traded for and had become the second S.D., P.B. & L.J. Ry No. 2, was disposed of).

Another Baldwin locomotive, an older tender engine named ‘Captain Jadwin’, was also transferred from the Coronado Railroad (E. S. Babcock owned the Coronado Railroad too) and became L.A. & S.D.B. Ry. No. 3. The coal-burning steam locomotives were also converted to burn fuel oil at about this time.

The Pacific Beach railroad’s right of way originally entered Pacific Beach from the east over what are now Mission Bay Drive and Garnet and Balboa avenues in order to avoid a race track at the northeast corner of Mission Bay. By 1906 the race track had been abandoned and the Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railway proposed to shorten its route and eliminate the sharp curve around the race track by realigning the right of way across the former race track property following the route of today’s Grand Avenue (then called Ivy Avenue). The proposal was approved and work began at a point south of the former race track in January 1907. The ‘Captain Jadwin’, L.A. & S.D.B. Ry. No. 3, was used to haul the work train.

In La Jolla the Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railway laid tracks on Silverado Street from its right of way on Prospect Street to Ivanhoe Avenue and established a new depot at the corner of Silverado and Ivanhoe in 1907. The line was then extended on Silverado, north on Exchange Place and west on Prospect where it joined the original line near the site of the old La Jolla depot at Prospect and Fay, forming a loop.

Further south, the railroad acquired the two blocks on either side of Rushville Street between railroad’s right of way and Draper Avenue (then Orange Street). The city closed that block of Rushville Street and the railroad used the property for an engine house and a ‘wye’, tracks that entered the engine house from the main line in either direction and allowed engines to turn around by backing out in the other direction.

The construction projects in 1907 had improved certain sections of the line but in many places trains were operating over tracks originally laid twenty years earlier and not necessarily in the best condition. On January 16, 1908 the 1:55 train from the San Diego depot was steaming through Middletown ‘at a fair rate of speed’ when the former Baldwin dummy that had been rebuilt as L.A. & S.D.B. Ry. No. 1 derailed and turned over on its side. The engineer, Thomas Robertson, was pinned in the engine’s cab and scalded to death by steam and the fireman, Thomas Fitzgerald, was also badly burned and died 10 days later. The passenger cars remained upright on the tracks and no passengers were injured. The railroad blamed the accident on ‘spreading of the rails’, saying that the spikes that held one of the rails had come loose and the rail had shifted. The original 35-pound rails were in the process of being replaced by heavier 60-pound rails but that work had not yet occurred at the site of the accident.

In the week following the accident nearly 200 residents of Pacific Beach and La Jolla signed a petition asking the city council to investigate the ‘conditions and methods’ of the railroad since their ‘comforts and conveniences’ and even their lives were at risk when ‘forced to use’ the railroad. The petition claimed that railroad was in a ‘frightfully dangerous condition’; many of the ties were rotten and spikes could be extracted with the fingers. The engines and cars were old and small, out of date and without the safety equipment the law required. The petition added that ‘the convenience or wishes of the citizens are in no way considered’ as to train service or the time table and the trains were ‘too few in number and are run at inconvenient hours’. The council agreed to an inspection trip over the line after which a majority concluded that the statements in the petition were exaggerated and the line was safe for travel. One council member dissented, claiming that the railroad had used the time since the wreck to cover up its worst deficiencies.

In an effort to modernize its old and small and out of date equipment a new McKeen gasoline motor car was purchased from the Union Pacific shops in Omaha in April 1908. The McKeen car was powered by a 200 horsepower six-cylinder gasoline engine mounted transversely behind the engineer in the front of the car. It was 55 feet long with a sharp ‘wind splitter’ nose and round windows resembling portholes. An identical McKeen car had been delivered to Babcock’s Cuyamaca railroad a month earlier and had debuted by taking a party of dignitaries on a ride over the Cuyamaca line to its end at the Foster station then back and through the city to the La Jolla line and on to La Jolla for lunch. The San Diego Union reported that the car worked in ‘splendid form’ throughout the entire trip and was the forerunner of a large number which would quickly follow since it had been clearly demonstrated that it is most practical (this car, named ‘Cuyamaca’, was recently rediscovered and brought to Ramona where it is being restored).

In a ‘Notice to the Public’ the La Jolla railroad announced that its new Union Pacific Gasoline Motor Car ‘La Jolla’ would begin operating between the ‘central loop’ in San Diego and La Jolla on Monday, April 20, 1908, making three round trips per day. The motor car would depart from the Brewster Hotel, corner of Fourth and C streets downtown, at 8:00 and 10:00 AM and 2:30 PM and return from the Cabrillo Hotel in La Jolla at 9:00 AM and 1:00 and 5:15 PM.

The central loop had been added to the C and Sixth street line, running on F Street from Sixth to Fourth and on Fourth from F to C, where the Brewster Hotel stood at the corner of Fourth and C. From Fourth Street outside the Brewster the motor cars would turn west onto C Street, arriving at the depot at the foot of C five minutes later, then continuing to Pacific Beach and La Jolla. On their return they would turn east from the depot onto C street, then south on Sixth, west on F, and north on Fourth to the Brewster.

In La Jolla the motor cars ran over the Silverado Street loop, east on Silverado to Exchange Place then west on Prospect, stopping in front of the Hotel Cabrillo across from Herschel Avenue. The loops at either end of the motor cars’ runs were necessary because the motor cars were ‘single ended’ and could only be driven in one direction. They did not have a reverse gear but could be backed up if necessary by stopping the engine, adjusting the camshaft and then restarting the engine in reverse.

The railroad’s notice to the public added that the three daily round trips by steam trains from the terminal depots would continue as at present (at the time the railroad’s franchise did not allow steam engines to run over downtown streets). The timetable showed steam trains leaving the La Jolla depot at Silverado Street and Ivanhoe Avenue for the San Diego depot at the foot of C Street at 7:15 and 10:45 AM and 4:15 PM daily (plus 7:15 PM Saturdays) and returning at 9:00 AM and 12:30 and 5:30 PM daily (and 11:15 PM Saturdays). The steam engines could be driven in either direction and at the end of their runs they could uncouple from their trains, pass around them on a second track, couple to the other end of the train and head off in the other direction without turning around.

In December 1908 the railroad announced that due to the great popularity of the La Jolla line since the introduction of the new gasoline motor car it was opening an ‘uptown ticket office’ with a waiting room at the corner of Fourth and C streets, where most passengers boarded the car for its trip to Pacific Beach or La Jolla.

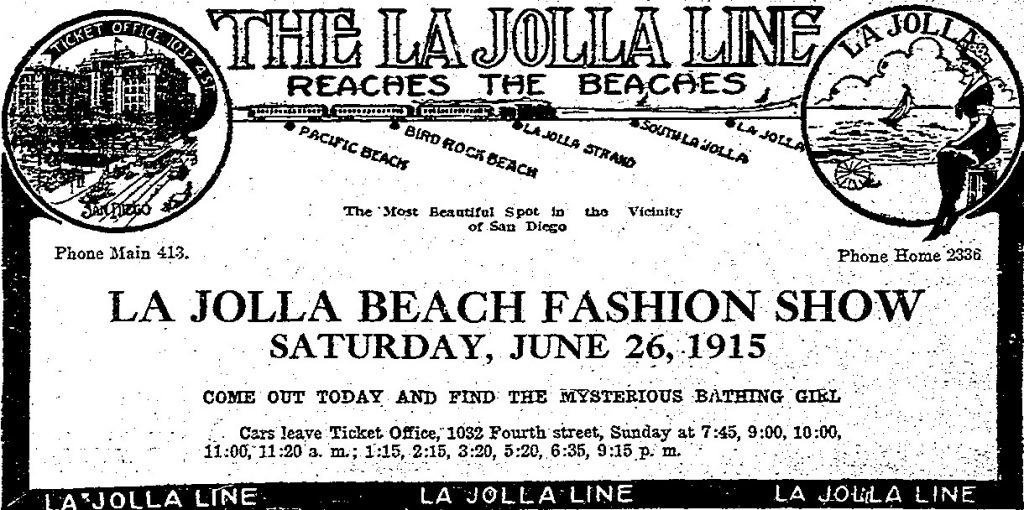

A second McKeen car, said to be capable of faster speeds and of negotiating steeper grades, was received in April 1909. According to the San Diego Union, it was ordered on account of increasing traffic over the line and to prepare for Sunday and summer travel. Both motor cars were painted ‘a rich Tuscan red’ and became known as ‘red devils’, or ‘submarines’ or ‘torpedoes’ because of their porthole-like windows. An ad in the Union advertising ‘Torpedo Flyers’ to La Jolla announced that steam trains would not operate on the La Jolla railway on Sundays. There would be eight gasoline motor cars each way and two of these trips each way (at 9:30 and 11:30 from San Diego and 3:00 and 6:15 from La Jolla) were ‘Flyers’; only 30 minutes between the Brewster Hotel, Fourth and C, and Cabrillo Hotel, La Jolla with no stops en route. The fare was 50 cents round trip.

A year later the timetable still showed four motor cars arriving and departing from Fourth and C daily. Four steam trains arrived and departed from the depot at the foot of C, plus the Saturday night theater train. The steam trains still did not run at all on Sundays, when they were replaced by four additional round trips by motor cars. After June 19, 1910, the steam trains also began departing from Fourth and C with four round trips daily, except Sundays, apparently due to a change in the railway’s franchise agreement. In addition to the steam trains there were five daily round trips by the gasoline cars, plus a late-night run on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays and three additional cars on Sundays when the steam trains did not run at all. In June 1912 the timetable was expanded to ten departures daily and Sundays, plus the late train on Saturday nights. Four of the trains were steam trains (three on Sundays) and the others gasoline motor cars. The same schedule with minor variations continued into 1913 and 1914.

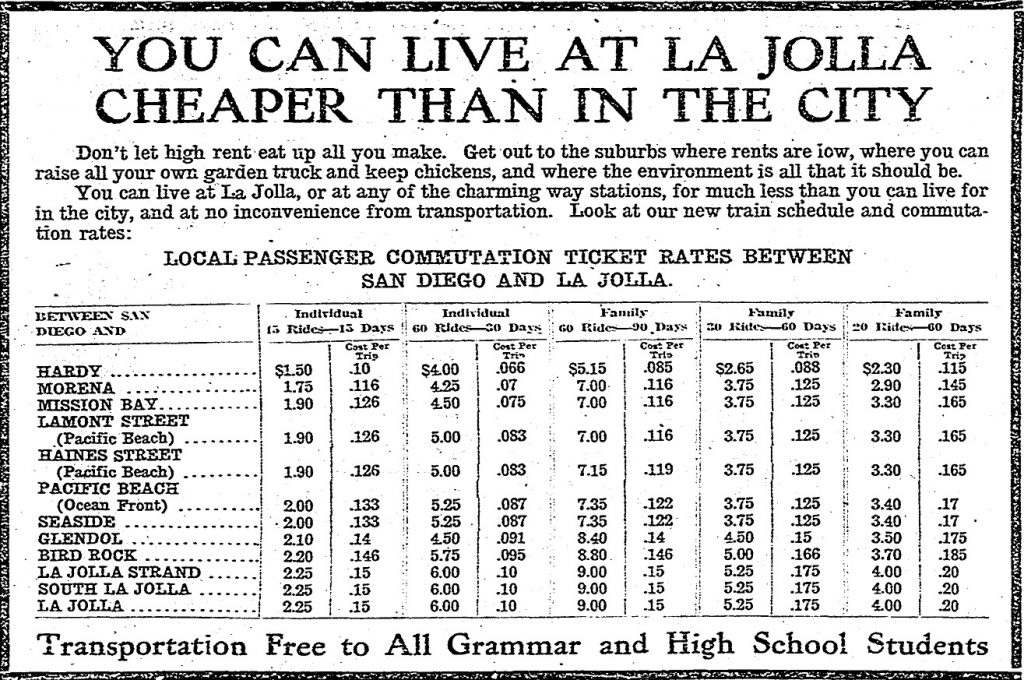

The increased traffic on the La Jolla line in these years was due in large part to the growing number of residents served by the line. The 1910 United States census had counted about 1000 residents in Pacific Beach and La Jolla combined, up from about 300 in 1900, and the 1920 census would count about 600 in Pacific Beach and 900 in La Jolla. The railroad encouraged this growth with advertisements in the San Diego Union.

La Jolla was also growing in popularity as a tourist destination, and the railway did its part with advertisements promoting ‘the most beautiful spot in the vicinity of San Diego’.

Although the number of potential passengers kept rising during these years, the number who had the choice of a new and more convenient way to reach the beaches was growing at an even faster pace. The first automobile arrived in San Diego In 1900 and in 1903 there were still only about twenty cars on the streets (including two Cadillac runabouts in Pacific Beach). In 1910 the number of automobile registrations in San Diego was estimated at 750 and by 1915 it had risen to about 3000, about one for every 18 residents. The main highway from San Diego to the north passed through Pacific Beach and La Jolla, paralleling the La Jolla railroad, and by 1919 it would be fully paved. The growing number and improved quality of automobiles accompanied by expansion of the city’s road system eventually made cars the first choice for travel to Pacific Beach and La Jolla. ‘Those who do not go in their own machines can take the 2:30 La Jolla car from Fourth and C streets’ was the advice of the San Diego Floral Association for a tour of the gardens of Miss Kate Sessions in Pacific Beach in 1915. By 1920 more than 12,000 automobiles would be in use by San Diego’s 75,000 residents.

The growing number of automobiles on public streets also presented conflicts with the La Jolla line’s right of way in those streets. In 1913 the La Jolla Chamber of Commerce filed a complaint with the city clerk asking that the railroad be compelled to cease stopping its cars on the street in such a manner as to hold up traffic and make the operation of automobiles dangerous. The operation of automobiles was particularly dangerous at railroad crossings; five people were killed and three injured in 1916 when a Los Angeles – San Diego automobile stage was hit by a northbound La Jolla train at Glendol, where the coast highway on La Jolla Boulevard crossed the tracks and became Turquoise Street in Pacific Beach. That collision was blamed on the undue speed and negligence of the driver of the automobile, who was among the fatalities, but in other cases drivers successfully sued the railway for damages resulting from collisions between cars and trains.

The railway’s acquisition of the McKeen cars in 1908 and 1909 had been an effort to upgrade and modernize its antiquated steam-powered equipment but the gasoline-powered motor cars turned out to be a poor choice for the La Jolla line. As their aerodynamic shape suggested they were designed for speed; they were geared for 90 miles per hour and the first car actually averaged 60 MPH under its own power when delivered to San Diego from Omaha. In San Diego, the cars would be operated at much lower speeds over a rough roadbed with many sharp turns, including miles on city streets (even the non-stop ‘Torpedo Flyers’ took 30 minutes for the 15-mile trip between San Diego and La Jolla, an average of 30 MPH). The La Jolla line also included steep grades, particularly the run from near sea level at the foot of Grand Avenue to over 100 feet at Bird Rock which averaged nearly 2%. The gear ratios were lowered before the cars were put into service but over time the slow speeds, steep grades and frequent starts and stops put excessive strain on their running gear, particularly their clutches. Within two months of the arrival of the first car in 1908 the San Diego Union reported that it was out of commission several days for clutch repairs. According to San Diego railway historian Richard V. Dodge the McKeen cars’ clutches had to be ‘pulled out’ every three weeks.

Ever since the first McKeen car debuted in 1908 the railroad’s time cards had noted which trains were steam trains and which were motor cars. A new time card on August 29, 1914, did not make that distinction and there was no further mention of the cars in the railroad’s time cards or in news stories about the railroad. Richard Dodge explained that the motor cars ‘lasted to about 1914’ and were ‘disposed of about 1916’. The railroad had acquired another steam locomotive about 1912, a 2-4-4 built in 1889 which became L.A. & S.D.B. Ry. No. 4, and it assumed some of the gasoline cars’ former workload. Another steam locomotive, built in 1881 and acquired in 1915, became L.A. & S.D.B. Ry. No. 15 and also saw service on the line. The steam locomotives required maintenance as well but according to R. P. Middlebrook in ‘High Iron to La Jolla’, their crews could often keep them running with simple repairs using the metal from Prince Albert tobacco tins and baling wire.

In November 1916 E. S. Babcock announced that the La Jolla Railway would deploy a new fleet of gasoline motor cars intended to meet jitney bus competition. The new cars would be essentially automobiles designed to run on rails and would be ready within the next few months. The steam trains would not be abandoned but would be run at times of heavy loads.

The new type of gasoline motor car was constructed by the Ort Iron Works in San Diego. It was built on a Mack truck chassis with a coach body and could carry 30 people at a speed of 35 miles per hour, enough to maintain a fast schedule between San Diego and La Jolla. A trial trip of the ‘made in San Diego’ motor car in April 1917 carried a party of businessmen to La Jolla as guests of the Ort Iron Works, an event that was predicted to foreshadow the establishment in San Diego of the car-building industry. The car made the trip to the ‘cave suburb’ in 33 minutes and there was ‘an evident absence of disagreeable vibration from the engine’. It was soon put into service as L.A. & S.D.B. Ry. No. 51. However, the predicted car-building industry was never established and No. 51 was the only gasoline motor car of its type seen in San Diego.

In October 1917 the Saturday night train to La Jolla pulled by engine No. 15 was accidentally switched off the main line onto the ‘wye’ and into the engine house at Rushville Street where it ran into the No. 51 motor car and drove it through the back wall. No passengers were injured but the front of the motor car was crushed and both No. 15 and No. 51 were removed from service for repairs. K. Fritz Schumacher was a Pacific Beach resident who depended on the railway to arrive in San Diego in time for his first class at San Diego High School. He reported that after the incident that sidelined both No. 15 and No. 51, and since engine No. 2 was undergoing a major maintenance operation, the railroad pressed No. 4 into service in spite of its sad state of disrepair and that he was tardy for several days.

The La Jolla line’s route from its San Diego depot to Old Town was east of the Santa Fe tracks, but just north of Old Town it crossed over the Santa Fe tracks and continued across the San Diego River toward Morena on a route west of the Santa Fe. The crossing outside of Old Town was a grade crossing and the Santa Fe had the right of way; the La Jolla train was supposed to stop and proceed only when there was no traffic on the Santa Fe line. On June 30, 1917, engine No. 4 (running backwards) was pulling a combination passenger/express car and an ordinary passenger car southbound to San Diego when it failed to stop at the crossing and was struck by a southbound Santa Fe freight train. Apparently No. 4’s brakes had failed and the crew was unable to bring it to a complete stop before it entered the crossing, but they were credited with stopping it within the crossing so that the Santa Fe engine struck the mostly empty baggage half of the combination car and not the passenger sections or the engine. The only injury was to a girl who was getting off at the upcoming Old Town stop and was standing near the door, but her injury was serious and she ended up losing a leg. The papers pointed out that the accident could have been much worse; one of the boxcars in the Santa Fe train was full of dynamite

In August 1917 the state railroad commission gave the La Jolla railway permission to increase fares and reduce service to three trains in each direction on weekdays and four northbound and five southbound on Sundays. The changes were blamed on increased competition from privately owned automobiles, although jitneys were not considered an active item of competition at that time. The commission also told the railway that some other cheaper method of transportation must be substituted for the steam trains that the line still depended on for much of its service. Engine No. 1, the rebuilt Baldwin dummy that had derailed and turned over killing its crew in 1908 had been scrapped earlier in 1917 but the railway was still using one of the original Baldwin dummies from 1888, rebuilt as a tender engine and numbered No. 2, the ‘Captain Jadwin’, built in 1880 and acquired in 1906 (No. 3), engine No. 4, built in 1889 and acquired about 1912, and No. 15, built in 1881 and acquired in 1915. The equipment roster was further reduced when engine No. 2’s tender derailed and turned over at Bird Rock while pulling a northbound train in reverse with the tender leading. That tender was replaced by the tender from engine No. 3, the ‘Captain Jadwin’, and engine No. 3 was then sold for scrap.

In 1917 the federal government nationalized the railroad industry to ease the congestion and general dysfunction that resulted from numerous competing railroad companies attempting to work together to support the war effort during World War I. To clear the rails for freight service, particularly to ports on the east coast, the United States Railroad Administration required railroads to raise fares and eliminate discounts to discourage passengers and reduce the number of passenger trains. Although the Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railway attempted to secure exemptions from this policy it was required to cancel round trip fares and increase the one-way fare by 10 percent in July 1918.

Continuing to lose money and with its equipment unreliable and ridership in decline the Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railway company filed an application with the state railroad commission in September 1918 for permission to discontinue service and dismantle and dispose of its property. The San Diego Union quoted E. S. Babcock as confirming that he was going to ‘scrap’ the railroad and sell the material to pay the debts of the company: ‘The road has cost me a great amount of money and I can no longer carry the burden’. The Union referred to a summary of the matter issued by the railroad commission in which the railroad stated that notwithstanding good service the traffic had steadily diminished and that this was due in great measure to the advent of the privately-owned automobile and more recently to the operation of a public stage line. The commission added that the railroad and equipment were old and in poor condition.

The railroad commission postponed its decision to allow the people of La Jolla time to formulate a plan for substitute service, with the provision that the La Jolla chamber of commerce would guarantee any deficit in the line’s operation. The plan for substitute service envisioned extending an existing electric line on Mission Boulevard in Mission Beach, the Bay Shore Railroad, from its terminus at Redondo Court to Grand Avenue and from there over the former La Jolla line right of way to La Jolla. The Bay Shore line, completed in 1915, connected with the Point Loma Railroad in Ocean Beach which provided electric service from downtown San Diego.

In December 1918, however, with no funds on hand to pay operating expenses, service was ‘altogether discontinued’ between San Diego and La Jolla. Most of the railroad’s locomotives and rolling stock had been sold for scrap earlier in 1918 and the railroad’s last working locomotive, No. 2, the original Baldwin dummy rebuilt as a tender engine by the Coronado Railroad, had broken down again. According to the report in the San Diego Union, the railway company had hired an auto stage over the last few months whenever the engine broke down but that even that expedient had become financially so burdensome that it had to be discontinued.

The application to discontinue service and dismantle and dispose of property was approved In January 1919 and the dismantling and disposition of the railroad was soon under way. The San Diego Union reported in November 1919 that six hundred tons of steel, part of the equipment of the disbanded La Jolla railroad, would be loaded aboard the steamship Colorado Springs to be shipped to Japan. The last working locomotive, Engine No. 2, was sold to a lumber company in the Los Angeles area.

The proposal to extend the Bay Shore electric line to La Jolla never happened but in 1923 the San Diego Electric Railroad built a new fast streetcar line from downtown to Mission Beach, continuing along Mission Boulevard to Grand and along the La Jolla line right of way as far as Bird Rock. At about Via del Norte the new electric line departed from the original right of way and turned toward the northeast, meeting Fay Avenue and continuing on Fay to a terminal at Prospect Street near to the location of the first La Jolla depot. This line also eventually succumbed to automobile traffic and was abandoned in 1940. By 1949 the entire system of electric railways in and around San Diego was gone.

Automobile traffic has continued to grow and has outpaced the expansion of roads and highways, leading to traffic congestion and gridlock. Additionally, emissions from automobiles, most of which are powered by gasoline engines, have been shown to be a major cause of air pollution and a major contributor to global climate change. A light rail system begun in the 1980s was intended to provide alternatives to automobile traffic in some areas around San Diego. One of these routes, the Orange Line between downtown San Diego and El Cajon, follows the route of the San Diego & Cuyamaca Eastern for much of its distance. The latest addition to this light rail system, opened in 2021, extends the Blue Line from downtown San Diego and Old Town to Pacific Beach and La Jolla, the same destinations reached by the Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railway and its predecessors. But while the route from Old Town parallels the old La Jolla line along the east side of Mission Bay with stops at Morena and Balboa Avenue the remainder of the route is entirely different, continuing north through Rose Canyon to a terminus near the University of California campus. The Balboa stop is miles from the beach at the eastern edge of the Pacific Beach and the university area is even further from Prospect and Silverado streets and the caves of La Jolla. The rail line that actually did ‘reach the beaches’ has been gone for over a century and is only remembered by the unusual width and alignment of certain streets that were once its right of way.