When San Diego became an American city in the middle of the nineteenth century it assumed ownership of the lands that had formerly belonged to the Mexican pueblo of San Diego. These pueblo lands originally extended from National City to Sorrento Valley, and from the ocean to a line close to the present route of Interstate 805, but as the city grew most of this city property south of the San Diego River was sold to private buyers. By the first years of the twentieth century ‘pueblo lands’ had come to refer to the portion of the city lying north of the river. Only about 7000 acres remained under city ownership, most of it along the coast between La Jolla and Del Mar, and the city was still selling it off. In 1907 Pueblo Lot 1298, 160 acres, was sold to the Marine Biological Association for the establishment of a biological station, to be funded by Ellen Browning Scripps (the biological station eventually became the Scripps Institution of Oceanography). In 1908 Miss Scripps also purchased Pueblo Lot 1338, 130 acres in the Torrey pine groves near the northern edge of the pueblo lands (which eventually were included in Torrey Pines Park).

In 1908 San Diego voters passed an amendment to the city charter stating that all pueblo lands owned by the city lying north of the San Diego River were reserved from sale until the year 1930. The charter amendment also added a tax of 2 cents on each $100 of valuation of property for the purpose of improving these pueblo lands. One idea for improving these lands was to plant trees, and in November 1910 a pueblo forester was appointed and a site selected for a headquarters on the mesa about three miles north of La Jolla. The site was in Pueblo Lot 1311 and the council authorized construction of a one-story frame dwelling and a frame barn there for the forester’s use. A building permit for the dwelling, valued at $1600, was issued in December 1910. Other building permits for sheds and garages on Pueblo Lot 1311 followed in 1911 and 1912. An irrigation system was also installed.

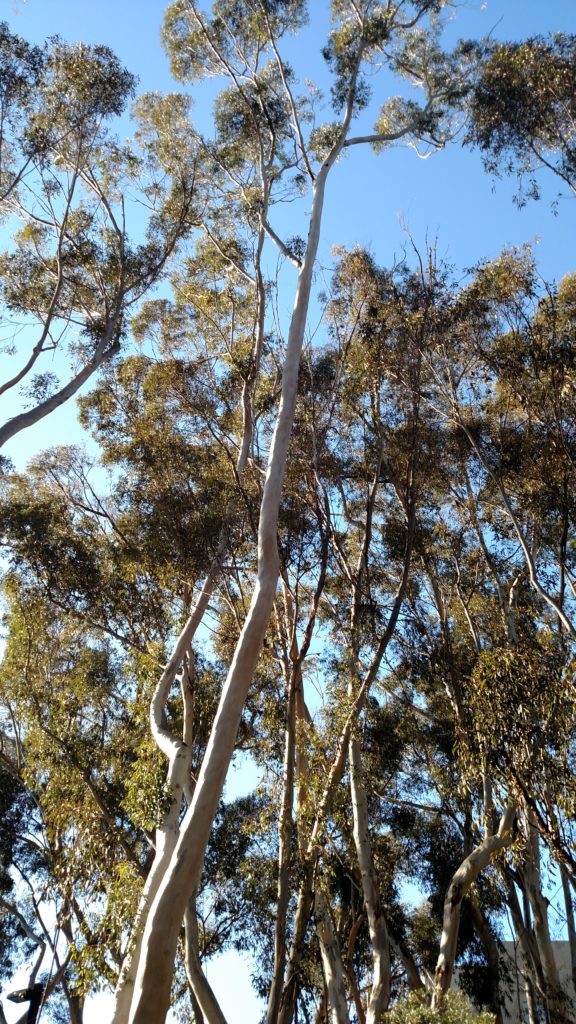

The pueblo forester was Max Watson, and he explained to the San Diego Union that for years the pueblo lands had been idle, bringing no revenue to the city and its barren hills being anything but beautiful to the eye. He planned to plant a portion of the land with eucalyptus trees which would bring in revenue as well as being another step in the direction of making San Diego a city beautiful. He claimed that the eucalyptus was the one tree that could be grown successfully on this land and would produce hardwood of commercial value in a short time frame. It could also be grown in poor soil and on slopes too steep for plowing.

By the spring of 1911 Watson had set out about 40,000 trees and had also cleared a small acreage for growing hay for use on the farm. Later in the summer of 1911 a nursery was built for propagating trees for future plantings and work begun on building roads and clearing additional land. He reported that without any water other than rainfall the eucalyptus trees had grown to about eight feet after a year and to fourteen feet after eighteen months. About 200 more acres of trees were set out in 1912, many on hillsides and land not adapted for general agricultural purposes.

The land under Watson’s control became known as the pueblo farm, and in addition to its potential for generating revenue and improving the scenery it turned out that it could also serve as a temporary home and provide work for the homeless and unemployed. In the winter of 1911 – 1912 the Union reported that ‘derelicts of the highways’ who formed a pitiable broken line along Rose Canyon Road coming from Los Angeles, where work had failed them, climbed the hill to the pueblo farm house to plead for jobs. ‘These poor fellows catch gophers and make ‘mulligans’ of them, they are so hungry’, Max Watson told the Union. ‘We are feeding as many of them as we can out here but they come beyond our capacity’ (the Union explained that a mulligan is a stew of any kind of meat with any kind of vegetables). The council voted to provide a ‘field outfit’ for 100 men to be set up at the pueblo farm. The winter of 1911 – 1912 was also when the International Workers of the World staged a series of violent demonstrations in San Diego. City and county authorities responded by arresting scores of demonstrators and in March 1912 they visited the pueblo farm to select a location for a ‘stockade’ in which to confine the additional hordes which agitators of the IWW had promised to bring to San Diego.

The decision to house the homeless and feed the hungry at the pueblo farm was not universally popular; the police chief in particular was opposed to this ‘philanthropy’. The reputation of its workers was reflected in a Union editorial which criticized an article in the rival San Diego Sun as ‘written by persons who would be better employed on the pueblo farm’. However, conditions had improved enough by the summer of 1912 that the camp for unemployed workingmen was closed. Watson reported that four hundred men in all were employed over the winter for ten days each at 50 cents a day but they had all since got better jobs as businesses opened with the close of the winter season. The workers had cleared 140 acres thickly covered with brush, planted 200 acres with 150,000 trees and turned several hundred acres into fertile fields. In July 1913 San Diego’s mayor and members of the city council made an automobile trip to the pueblo farm to inspect development of the city’s ‘wild property’ north of the river. They were treated to a lunch of fried chicken, mashed potatoes, green beans, frijoles, pickled beets and cold slaw, all raised on the farm. Although no-one had anticipated the humanitarian mission of the pueblo farm, Watson wrote in 1913 that it had been his greatest challenge and became his greatest satisfaction.

Although the pueblo forester had been tasked with creating a forest on the barren or brush-covered pueblo lands, an area in the northern section of these lands was already forested with Torrey pine trees, a rare species that only grew at this location and on Santa Rosa Island. In 1914 Max Watson transplanted about 1000 young Torrey pines grown from seed at the pueblo farm nursery among the older trees with the idea of preserving the Torrey pine groves as a national monument. The Torrey pines had long been a popular tourist destination and a road to the pine groves from La Jolla had been established across the mesa. With the increase in the popularity of automobiles in the early twentieth century the road had been widened and the steep grades at either end of the mesa, the biological grade above the biological station (now La Jolla Shores Drive) and the Torrey pines grade above the Penasquitos lagoon, had also been improved. This road linked the route from San Diego through Pacific Beach to La Jolla and the state highway from the Los Angeles area which ended at Del Mar into a continuous ‘coast highway’ from San Diego to the north. Other roads led south from the mesa to La Jolla via ‘Pueblo Farm Canyon’ and to San Diego via Rose Canyon, north to Sorrento Valley and east to the Scripps’ Ranch at Miramar. Since the roads across the mesa crossed city pueblo land and the city was responsible for their construction and maintenance, much of the labor was provided by workers from the pueblo farm, including city prisoners and the unemployed. In the days before most roads were paved they were sprinkled regularly with water during the dry season to control dust, and in 1915 a reservoir with a capacity of 100,000 gallons was excavated by pueblo farm laborers (the reservoir is now the site of the National University campus).

By the end of 1915 the city council had concluded that road construction was a better use of money raised from the 2-cent property assessment for improving pueblo lands and decided to do away with the operation of the pueblo farm. Cultivation at the farm would be discontinued except for the harvest of the hay crop, which was used to feed the city’s teams. The buildings would be used as a camp for laborers building the Torrey Pines boulevard and other road projects on the pueblo lands, which all radiated from the pueblo farm. At the beginning of 1916 the pueblo farm, along with the departments of water, sewer, streets, harbor, city engineer and public buildings was consolidated into a single operating department presided over by a city manager. The positions of the former heads of its constituent departments, including the city forester, were eliminated. Max Watson continued to head the pueblo farm as a general foreman, but soon resigned and took a job out of town. His position as caretaker of the pueblo farm was taken over by Frank Sessions, brother of the well-known horticulturist Kate Sessions, who began his duties in January 1916. One of his first tasks was repairing damage to the roads leading down from the mesa to La Jolla which were washed out in the storms of January 1916 that had eroded roads and destroyed dams and bridges all over San Diego County (the ‘Hatfield flood’).

Events in the wider world were also destined to play a part in the future of the pueblo farm and San Diego’s pueblo lands. A war among European powers begun in 1914 had grown to involve much of the world and although the United States remained neutral until 1917 steps were taken to build up the military. As part of the military build-up the U.S. government petitioned San Diego’s city council in 1917 for a lease on a large tract of the pueblo lands to be used as a maneuver field for the thousands of marines to be stationed in and around San Diego. According to the Evening Tribune, the marines’ request was for 25 pueblo lots, practically all city lands north of Rose Canyon, extending from Rose Canyon to Torrey Pines Park and from the ocean to Sorrento Valley. The marines’ maneuver field would be contiguous with the army’s Camp Kearny to the east and would be linked to it by the Miramar Road. The city had several pueblo lots for pasturage and four pueblo lots under cultivation and some buildings, and these properties were not to be used by the marines. The marines also agreed to not close any of the permanent highways through the lands and not to chop or damage any Torrey pines or other trees in the park. The marines did receive the lease and established a rifle range east of the pueblo farm buildings and south of the Miramar Road.

Road construction through the pueblo farm continued during 1918. In February the city manager announced that a new route for a paved highway from the Torrey Pines grade to the biological station had been decided on. From the biological grade it would follow the existing Camp Kearny road to the pueblo farm, then turn north to a new section of the Torrey Pines road, which would be paved. In December 1918 the news was that by January 1 perhaps automobile owners could travel into La Jolla from the north over a fine paved highway, as the city’s part of the work connecting the state highway at Torrey Pines with the paved biological grade was to be completed by then. In January 1919 the Southern California Highway Conditions column by a representative of the Automobile Club of Southern California described the Los Angeles Coast Route from San Diego:

go either by way of Ocean Beach or Old Town to the junction of Pacific Beach over good dirt road, thence follow through to La Jolla city, which is paved within its limits; thence a short stretch of dirt road to the foot of the Biological grade; thence pavement to the top of the grade. A short stretch through the Pueblo farm house for one-quarter of a mile will bring you to the new pavement on the mesa. From the mesa to Los Angeles the road is paved.

(The ‘junction of Pacific Beach’ was the intersection of Garnet Avenue and Cass Street, where the branches of the coast highway that ran east (via Old Town) and west (via Ocean Beach) of Mission Bay met before continuing north on Cass and Turquoise streets to La Jolla Boulevard)

Also in January 1919, the city council decided that since Superintendent Frank Sessions was doing the caretaker work and handling a lot of prisoners that the police supplied him with the pueblo farm should be placed under the control of the police department. Jail prisoners would be used as formerly and Superintendent Sessions would continue as caretaker temporarily. However, in April the council decided to take it back from the police and to authorize the city manager to resume charge of the city pueblo farm. The New Year’s 1920 review of the city in the San Diego Union reported that the pueblo farm, recently transferred to the operating department, had completed fall plowing of about 700 acres which was then being planted to wheat, oats and barley. These lands were soon to be made more valuable by irrigation from a water line from Del Mar to La Jolla. Since the city could not sell this land until 1930 it was planned to lease tracts for farming purposes.

In 1919 the city council had designated the pueblo farm as a site for a hog ranch to dispose of city garbage and in April 1920 the news was that its sows had presented the city with litters aggregating 60 baby pigs. The Union reported that there were about 100 young pigs at the farm and when they were grown to a weight of about 200 pounds the manager of operations would order them sold. As the hog ranch on the pueblo farm became established the canyon south of the farm came to be known as Hog Canyon. When work on widening and straightening the biological grade was undertaken in 1925 the first step was the preparation of a detour between La Jolla and the Torrey Pines mesa by widening and grading the road through Hog Canyon. In 1927 the city council agreed that Hog Canyon should be given the more respectable name of La Jolla Canyon; the Union reported that the councilmen took the view that the La Jolla Women’s club was right in demanding the change, as ‘hog’ was in no way adapted to La Jolla’s scenic beauty and aesthetic atmosphere. The new La Jolla Canyon highway proved to be popular with motorists who wanted to avoid the biological grade and it was also paved in 1928. In 1930 the La Jolla Canyon road, formerly the Hog Canyon road, was officially renamed Torrey Pines Road.

The highway across the Torrey Pines mesa and the Torrey Pines grade continued to be widened and improved as traffic increased on the coast highway and in 1930 arrangements were made to quarter the highway workers at the city pueblo farm to save the long trip back and forth to the city. The highway through Rose Canyon was paved in 1930 and state highway officials joined local dignitaries in December for opening ceremonies at the junction of the Rose Canyon highway with the Torrey Pines highway at the city pueblo farm. In 1931 a new route for the Torrey Pines grade was completed and the combined highway became known as the ‘million-dollar gateway to the north’. In 1935 it was officially renamed Pacific Highway.

Max Watson had resigned as pueblo forester in 1916 but in 1934 he visited the site of the pueblo farm where the Union reported that the eucalyptus trees that were mere sprigs when he superintended their planting then towered 20 to 30 feet high in groves and along the highway on the mesa from Torrey Pines Park to the biological station on the old La Jolla grade. ‘In those days, the mesa south of Torrey Pines was barren of trees. We planted more than 100 acres of them, not counting those planted along the highway’, he said.

The pueblo farm was seldom in the news after the 1930s. In December 1945 a truck loaded with ammunition from a navy ship in San Diego Bay to a weapons storage site near Fallbrook caught fire and exploded on US 101 about 400 feet south of the La Jolla Junction, where US 101, La Jolla Shores Drive, Torrey Pines Road and Miramar Road came together. The explosion was massive, heard as far away as Palomar Mountain, and caused widespread damage in the vicinity. Fortunately, the driver had escaped the truck before the fire reached the ammunition and had alerted nearby residents. No-one was killed but a number of people were injured by flying glass from shattered windows, including a resident of the city farm. A final news item appeared in 1951, when the city published a notice requesting sealed bids for houses for sale to be moved by purchaser. One of the houses was the Keeper’s House at Pueblo Farms on Pueblo Lot 1311.

The site of the pueblo farm has undergone tremendous changes in the intervening decades. In 1956 a majority of San Diego voters approved a proposition authorizing the city to sell 40 or 50 acres of pueblo land in Pueblo Lot 1311 southwest of La Jolla Junction for use by the University of California should the school expand its campus at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. In 1958 the university administration began negotiations for the acquisition of a 65-acre site in Pueblo Lot 1311, west of US 101 and southwest of Miramar Road, for an Institute of Technology and Engineering. City voters also approved transfer of other pueblo lands if requested by the university regents and in 1960 the regents voted to acquire 482 acres of Torrey Pines mesa for development into a general university campus. The first land transfer would be 58 acres in Pueblo Lot 1311, between US 101 and La Jolla Shores Drive, south of Miramar Junction. The marine rifle range on leased pueblo land east of the pueblo farm had been acquired by the government in 1937 and named Camp Matthews in 1942, but by the 1960s activities there had become incompatible with the growing population in the vicinity and in 1964 it was closed and its property also transferred to what became the University of California, San Diego or UCSD.

In 1959 Max Watson cited the University of California’s decision to build a campus near La Jolla as justification for his efforts to create a forest on the pueblo lands 50 years before. By transforming the barren hills around La Jolla into a scenic shaded area, the trees had greatly raised the value and attractiveness of the area. ‘I don’t think the university would have agreed to locate a branch campus there if it hadn’t been for that. We’re cashing in on what we did 50 years ago. Everybody thought it was a flop then, but it hasn’t turned out that way at all.’ Although the former pueblo farm has been transformed into a modern university campus, with laboratories, classrooms, dormitories, and a spectacular library, the area is still dominated by its eucalyptus trees, many of them growing in the neat rows planted by the prisoners and other unfortunates that Watson welcomed over a century ago.