In early 1903 O. M. Schmidt and A. J. Dula filed subdivision maps for the Fortuna Park and Second Fortuna Park additions south of what became Pacific Beach Drive and commissioned Dula’s brothers-in-law Murtrie and Wilbur Folsom as sales agent for the new tract. The Folsom Brothers’ ads in the Evening Tribune described Fortuna Park as a beautiful home spot, destined to be one of San Diego’s best suburbs, and where a $25 lot was likely to quadruple in value in a few months. They then embarked on a marketing expedition to the Arizona Territory where they expected to find eager buyers for summer homes surrounded by the cool waters of Mission Bay. There they sold dozens of lots to buyers in places like Morenci, Prescott, Douglas, and Bisbee, which is where they sold lots 39 and 40 in block 2 of Second Fortuna Park to O. W. Cotton for $40.

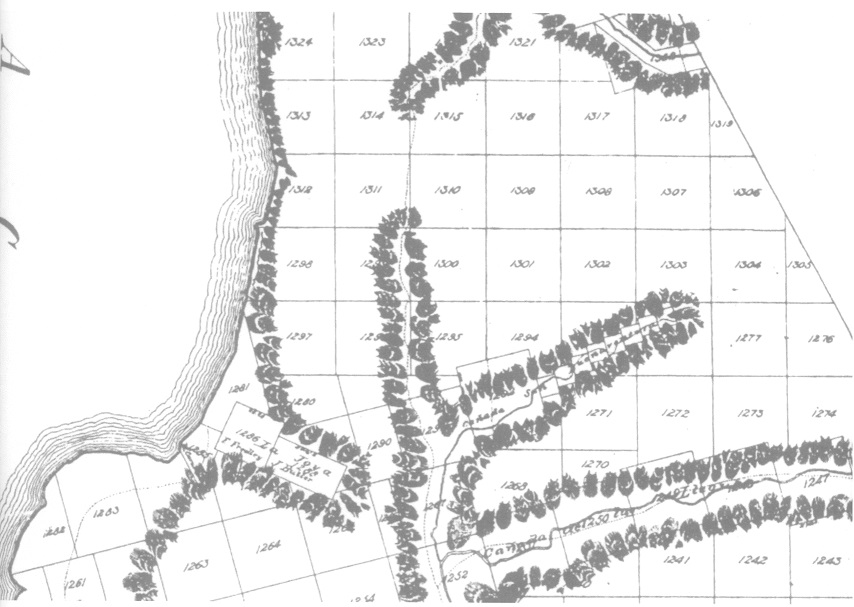

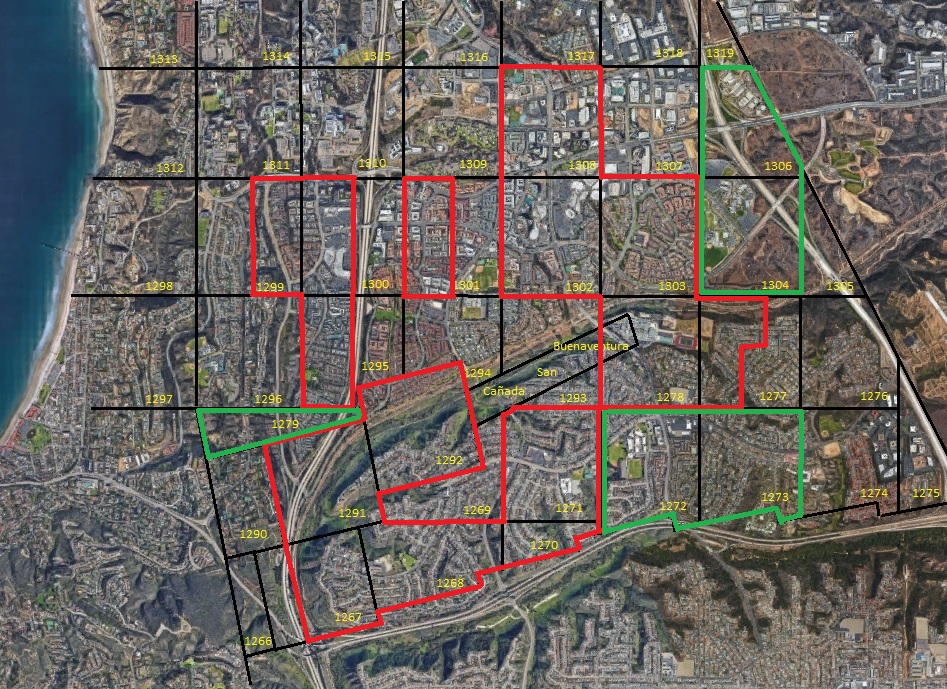

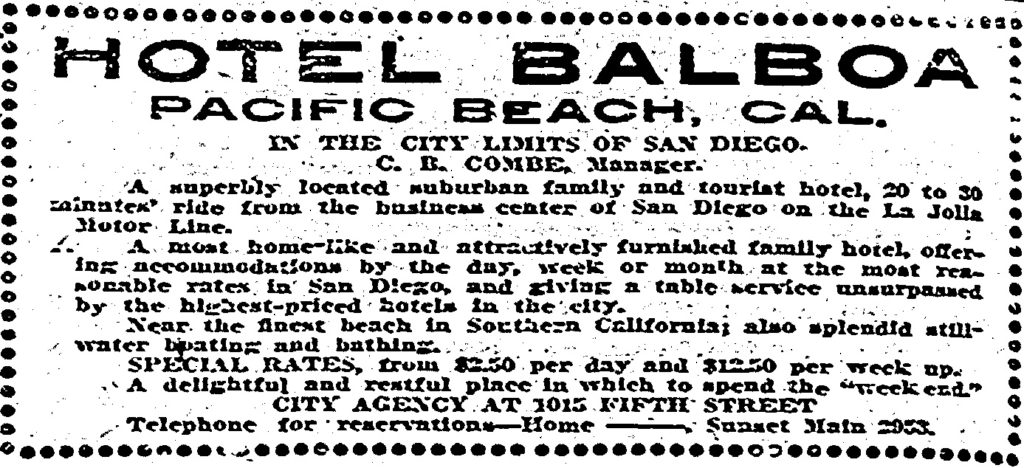

Oscar W. Cotton had been born in San Francisco in 1882 and was working at his first job in Bisbee, making $70 a month. He was apparently so impressed with the Folsom brothers’ sales pitch that he not only purchased lots for himself but also became their agent, selling Fortuna Park lots to other residents of the Arizona back country. In July 1903 Cotton came to San Diego to see for himself the properties he had bought, and had represented to others, and decided to stay and join the Folsom Brothers firm. In November 1903 Folsom Brothers significantly expanded their interests, acquiring O. J. Stough’s holdings of almost the entire territory of Pacific Beach. An ad in the San Diego Union a month later announced that the company would make improvements, including the erection of many sightly residences, that would make it the most attractive suburb of San Diego and insure its rapid development.

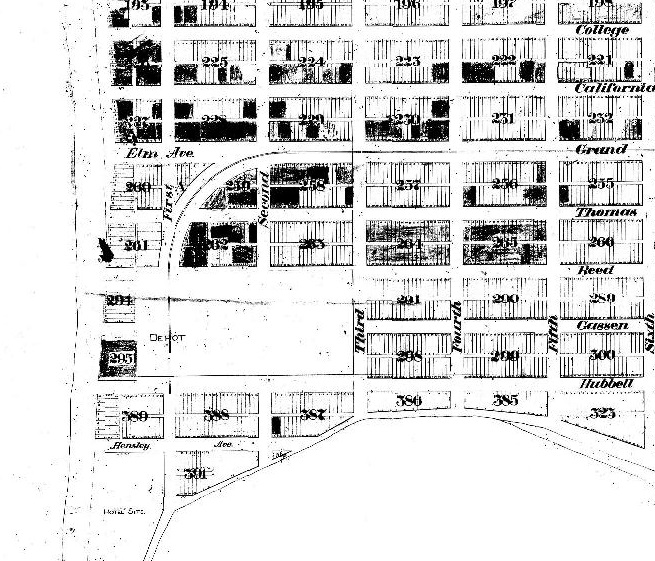

Work on the sightly residences was soon underway; the Tribune reported in December 1903 that the new concrete dwelling on Broadway near Sunset Avenue now being erected by Folsom Brothers was fast nearing completion and foundations had been laid by the same firm for the erection of four other structures, work upon which would be commenced within a few days (Broadway is now Ingraham Street and Sunset is Fortuna Avenue). In January 1904 the Tribune reported that Mark Folsom, their father, had laid the foundations for a handsome dwelling at the corner of Broadway and Thomas Avenue. The building would be constructed of concrete cement, elaborately finished on the exterior and surrounded by spacious lawns.

In February, the handsome office building of Folsom Brothers which was being erected at the corner of Broadway and Grand Avenue was fast nearing completion and would be ready for occupancy within a few weeks. This building was also of concrete cement and very attractive in its architectural design. Although the main part of the office would be devoted wholly to the business of selling building sites in Pacific Beach, there would also be a department to be used as the headquarters of the architect who would superintend the building operations of the firm.

The business of selling building sites in Pacific Beach was a good one for Folsom Brothers in 1904; the Evening Tribune reported that on occasion no less than five teams might be seen conveying prospective buyers through the suburb and along the famous ocean strand. Anticipating further growth in its real estate business the company filed articles of incorporation in August 1904. Murtrie Folsom became president and Wilbur Folsom vice-president of the new Folsom Bros. Co. and O. W. Cotton was named secretary and treasurer. The construction side of the business was also promising and in September the Pacific Beach Construction Company was incorporated with the Folsom brothers and Cotton as directors. A Folsom Bros. Co. ad in the Union explained that the construction company was organized primarily for the upbuilding of Pacific Beach property. It would manufacture and deal in all kinds of building materials, including the most modern and practical style of cement blocks, and would build houses of this and other materials. It was listed in the 1905 San Diego City Directory as Folsom Bros. Co. Building Department, alabastine stone and building material, at the same address as Folsom Bros. Co. Real Estate.

The next few years were busy ones for the Folsom Bros. Co. building department. The San Diego Union reported in October 1904 that developments of the past week in building improvements in Pacific Beach had surpassed those of any like period since Folsom Bros. Co. started their immense and comprehensive plans of development. The foundations and framework of no less than ten structures in various stages of completion could be found within a radius of only two blocks from the Pacific Beach Hotel. Some were store buildings and some residences and nearly all either in whole or in part being constructed of the patent cement-concrete building blocks manufactured by Folsom Bros. Co.

The Pacific Beach Hotel was at the center of the community at the time, the corner of Lamont and Hornblend streets, where the Patio restaurant is now (the hotel building later became the Folsom Bros. Co. sales office). The new store buildings included the ‘handsome two-story edifice’ of McCrary and Parmenter at the southwest corner of Grand Avenue and Lamont Street, a block south of the hotel, which ‘threw open its doors’ in January 1905 and which was constructed ‘in whole’ of concrete blocks. (this store, ‘the largest in the suburb’ in its day, became Ravenscroft’s grocery in 1913 and was later the Full Gospel Temple before being demolished in the 1950s). The residences in various stages of completion in 1904 included a number on Hornblend Street within two blocks of the hotel, some of which are still standing, including the home built for H. J. Breese at the northeast corner of Hornblend and Morrell (later the passion fruit ranch of Dr. H. K. W. Kumm) and the homes built for Anna Boulet and Ansel Lane (now the Baldwin Academy) on the north side of Hornblend between Jewell and Kendall streets. Outside of the central two-block radius, the Union reported that the magnificent home of James Haskins on Diamond Avenue, fast nearing completion in December 1905, was constructed partly of the concrete blocks manufactured by Folsom Bros. Co.

In 1906 O. W. Cotton was the author of a piece in the San Diego Union that promoted Folsom Bros. Co. as an establishment that had grown from three employees to having a payroll that included from fifty to sixty names. Their alabastine stone plant, a factory for the manufacture of artificial stone (concrete building blocks), had grown from a little experimental block yard in Pacific Beach employing four people to a third of a block downtown employing thirty people that furnished building materials for nearly every structure built in San Diego. And this was just the beginning of what they planned to accomplish.

In a memoir published in 1962 Cotton later explained that the experimental yard had actually been the engine house of the San Diego, Pacific Beach and La Jolla railroad near the foot of Grand Avenue, where Folsom Bros. had attempted to make concrete blocks from beach sand. It turned out that beach sand is too fine-grained to bind into blocks and the plant was moved away from the free source of this raw material to the downtown site where the blocks were made of coarser river sand. Even with better quality products, however, the venture was not profitable and the company soon got out of the concrete block business to concentrate instead on lot sales.

In December 1906 Folsom Bros. Co. announced a new ‘opening sale’ of 250 Pacific Beach lots beginning on January 1, 1907. Their ad in the Union explained that the company had just inaugurated a policy of improvement and development and homebuilding. The improvement and development would include grading permanent streets and boulevards and paving sidewalks. The homebuilding would be accomplished by the Pacific Building Company, which would be opening for business on January 1, 1907, and would build houses costing from $1,500 to $10,000 at Pacific Beach upon easy monthly payments about equaling rent (the lots themselves were another $250). Other Folsom Bros. Co. ads emphasized that the Pacific Building Company, an allied company, would build houses ‘for purchasers of lots from us’.

The Pacific Building Company had been incorporated in December 1906 with Cotton heading the list of five founding directors and stockholders and serving as president and general manager. The company would be allied with Folsom Bros. Co. and initially shared the same office at 1015 5th Street but the Folsom brothers were not included as directors or even stockholders of the new company. In early 1907 the report of building permits in the San Diego Union generally included at least one for Pacific Building Company in Pacific Beach or Fortuna Park. One week in April the building permits report in the Evening Tribune listed four permits for the company to be erected in Pacific Beach; two frame dwellings valued at $1800 each, one frame cottage, also $1800, and a cement cottage at $2800. In May the Union reported permits for two one-story frame cottages at Pacific Beach, one valued at $2600 and the other $2300, a two-story residence at $5000 and a cottage at $2300.

In June 1907, a report on developments in Pacific Beach mentioned that the Pacific Building Company was erecting a six-room house in Fortuna Park for Mr. DeHart and also a large cottage for Mr. Mott (actually Macht) on Missouri Avenue. It had just completed a large cottage for Mr. J. M. Asher, Jr., and a smaller one, and was then finishing a large house on Diamond Avenue. In July the Union listed two more houses started by the Pacific Building Company and credited the reorganization of Folsom Bros. Co. at the beginning of the year with generating so much activity that the arrival of freight cars full of lumber in the suburb was commonplace (the freight cars would have arrived at the West Coast Lumber Company siding off the La Jolla railroad line on Grand just east of Lamont, where the 7-11 is now).

Mr. DeHart’s home in Fortuna Park is no longer there but three houses built in 1907 in the 1100 block of Missouri, including the home built for Mr. Macht, are still standing . Other homes built by the Pacific Building Company also remain today in Pacific Beach. A building permit was issued in June 1907 for the one-story frame building on Reed Avenue between Lamont and Morrell streets to cost $1700 that still stands at the southwest corner of Reed and Morrell. In October 1907 the Pacific Building Company started work on the much larger house at Lamont and Beryl streets for the MacFarlands valued at $3500-$4000.

The large house that Pacific Building Company was finishing on Diamond Avenue in 1907 was intended for Cotton himself. In June the Union reported that Mr. and Mrs. O. W. Cotton had returned from a wedding journey to Yosemite, and that Mrs. Cotton, who had been Miss Violet Savage, would be remembered as one of the ‘charming members of the younger set in Los Angeles’. They were staying at the Hotel Robinson to await completion of their attractive cottage at Pacific Beach. That attractive cottage is also still there, at 1132 Diamond Street. While living in Pacific Beach Mrs. Cotton was noted for her musical talent; a former concert pianist, she entertained guests at Mrs. Haskins annual holiday reception for members of the Pacific Beach Reading Club. ‘The appreciative audience demanded many recalls and Mrs. O. W. Cotton continued to give rare pleasure to the parting guests to the very last’.

In 1907 Pacific Building Company and Folsom Bros. Co. shared an office and O. W. Cotton was a director and officer of both companies but in February 1908 the Evening Tribune reported that Cotton had disposed of his interest in Folsom Bros. Co. to devote his entire time to managing the Pacific Building Company, where he was president and general manager. W. W. Whitson, president of the Hillcrest Company, bought out Cotton’s interest in Folsom Bros. Co. and was installed as first vice-president and treasurer (Murtrie Folsom remained as president and Wilbur Folsom was moved to second vice-president and secretary). In a 1984 interview with the San Diego Union, Cotton’s son John claimed that there had been a ‘falling out’; the Folsoms wanted to build houses out of concrete and his father thought that was pure folly. Whatever the reasons, separation from Folsom Bros. Co. allowed Pacific Building Company to expand its home construction business beyond Folsom Bros. Co.’s base in Pacific Beach.

The Cottons also moved from Pacific Beach, selling their Diamond Street home to G. H. Robinson, a Folsom Bros. Co. salesman, in 1908. According to the Union, Mr. Robinson had been married in Los Angeles and had bought for his bride the beautiful home on Diamond formerly owned by O. W. Cotton. The Cottons first moved to Hillcrest, where they bought a lot from Whitson and had another home built by Pacific Building Company valued at $4000. In 1912 they moved again; the Union reported that among the many handsome homes recently completed in South Park was a beautiful two-story residence erected by the Pacific Building Company for O. W. Cotton, president of the corporation which had erected 532 buildings to date.

Most of these homes and the hundreds more built over the ensuing years were in the fast-growing communities served by streetcar lines radiating from San Diego. One such ‘streetcar suburb’ was the company’s Tract No. 4, built in 1910 at the end of the line that once ran out Imperial Avenue (then called M Street) and at the time just outside of the city limits (which then ended at Boundary Street). Most of the homes built by Pacific Building Company in Tract No. 4, or Sierra Vista, can still be seen in the Mountain View district of San Diego. Other tracts of inexpensive homes were developed in Normal Heights and East San Diego, also then outside the city limits along the streetcar lines on Adams and University avenues (at the time homes like these could be purchased for less than $1500; in 2019 one built in 1911 on the 30th Street streetcar line in South Park was the San Diego Union-Tribune’s example of what could be bought today for San Diego’s median home price, $560,000). Pacific Building Company also continued to build larger custom residences throughout the city, including the showplace home for Charles Norris on Collingwood Drive in Pacific Beach in 1913.

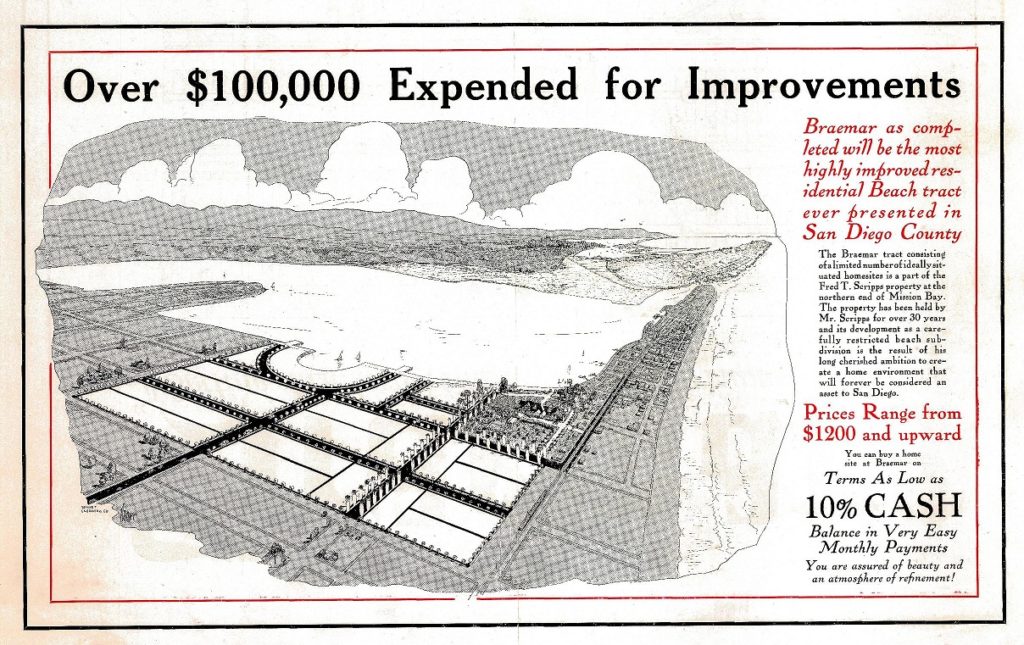

O. W. Cotton had started his real estate career with Folsom Bros. Co. and then departed to concentrate entirely on construction, but in 1926 he decided to get out of the building business and back into subdivision sales and general real estate practice. Readers of the real estate pages in the local papers in June 1926 would have seen an announcement that the Pacific Building Company was marketing a magnificent tract stretching from the hilltops overlooking La Jolla right down to the water’s edge but could not hit on a name to do it justice and were offering a $100 reward for a suitable name. A week later the Pacific Building Company announced a winner; the tract would be known as Monte Costa. The next week’s Evening Tribune carried an ad for Monte Costa, but it was attributed to ‘O. W. Cotton, Successor to Pacific Building Company’, and by the end of 1926 ads for Monte Costa were by ‘O. W. Cotton Real Estate’ (the tract was actually the Bird Rock subdivision and the new name never caught on). In November 1926 Pacific Building Company underwent voluntary dissolution but as late as 1930 the San Diego city directory still had a listing for ‘Pacific Building Company O. W. Cotton Successor’ (and an entry for ‘O. W. Cotton Successor to Pacific Building Company’ at the same address).

O. W. Cotton continued to be one of San Diego’s best known real estate personalities for decades. In 1946 he was joined by his sons John and William as partners in O. W. Cotton Co., later Cotton Management Co. and Cotton Co. He died in 1975 at the age of 93. Hundreds of homes built by his Pacific Building Company are still standing in San Diego’s former streetcar suburbs and even in Pacific Beach, where the company commenced operations with three houses in 1907.