Like the rest of the world, San Diego is suffering from the coronavirus pandemic which arrived in North America in early 2020. Once infected with the highly contagious virus, some people may have mild or even no symptoms while others experience severe respiratory distress which may develop into pneumonia and, particularly for the elderly and those with existing health issues, death. As yet there is no vaccine or cure and the only defense against its continued spread is ‘social distancing’. In San Diego and elsewhere this has taken the form of increasingly restrictive orders to prevent gatherings and require people to remain separated by at least six feet. Schools were closed, sports events were cancelled, restaurants and other gathering places were shut down. Only businesses deemed essential remain open, with employees required to wear face masks. People are supposed to stay home, and to wear a mask if they do leave home for essential activities. As of mid-April 2020, social distancing seems to be slowing the rate of infections but at the cost of massive disruption to the economy and to people’s lives. The current coronavirus pandemic and the official response to it is not entirely unprecedented, however. In 1918 the Spanish influenza epidemic entered the United States from Europe and eventually spread to San Diego, where thousands of people were infected and hundreds died. Then, as now, there was no cure for the disease and health authorities resorted to social distancing measures to control it.

The Evening Tribune first reported in mid-September 1918 that extensive epidemics of influenza had occurred at several army camps on the east coast and might be expected to appear in other camps soon. A few days later, an editorial in the San Diego Union noted that Spanish influenza had assumed epidemic proportions of virulent character in Europe and along the eastern coast of the United States, where it was prevalent in military training camps, but had not appeared anywhere in the west except for eleven cases from an army camp in the state of Washington. The Union quoted from a letter sent to a San Diego woman by her brother, a doctor in Berne, Switzerland, where there were 10,000 sick out of a population of 100,000. According to the doctor, the first precaution was to avoid infection by forbidding all assemblies, including theatres, concerts, churches and street crowds. Everyone should converse with their neighbor at a distance (the doctor added that kissing was almost unknown, indulged only by recklessly frivolous persons). The Union added that San Diego’s board of health had received ample warning and were taking every precaution in local camps and communities.

In the fall of 1918 the world was at war, with an alliance led by the British empire and France fighting imperial Germany on the western front in France and Belgium. The United States had entered the war on the side of Britain and France in 1917 and large numbers of troops were trained in camps around the country, including in and around San Diego, before being sent overseas, where they played a major role in bringing World War I to an end on November 11. In San Diego, the navy had taken over Balboa Park for one of these training camps, and since influenza seemed to spread through the movement of recruits through camps the first local precaution against influenza was to place the naval training camp in Balboa Park under a strict quarantine. The quarantine imposed on September 25 would be kept in place until all danger of an epidemic had passed. No civilians would be permitted to enter the grounds and sentries were posted at all the park gates. Although a number of suspected cases had been placed in isolation wards, officers initially declared that no actual cases had been discovered among the 5000 men in camp.

The San Diego area was also the site of a huge new army base; Camp Kearny had been set up in the summer of 1917 as a National Guard training center at a then-remote site that has since become Camp Elliott and the Miramar air station. By September 1918 over 30,000 troops were stationed at the camp, at a time when the civilian population of San Diego was about 75,000. In late September the Union reported that the strictest sort of a watch was being maintained at that camp for anything looking like the Spanish influenza, but that nothing which could be identified as such had appeared. No camp quarantine had been established and the medical authorities were loath to resort to one. On October 9, however, a quarantine was established as a precautionary measure, directing no officer, enlisted man or civilian to leave the camp. The camp still had no cases of Spanish influenza of its own but two cases were brought there by soldiers arriving from an eastern camp where it had been prevalent. They were placed in quarantine and others had had no communications with them.

A partial embargo was also imposed on Fort Rosecrans, the coast artillery base on Point Loma. Officers and men were forbidden to go to Los Angeles or attend theatres or other public gatherings in San Diego. The embargo would be extended to a real quarantine if the ‘menace’ approached any further from the north. Meanwhile, the funeral for the first San Diegan to die of Spanish influenza was held on October 1. Dr. Gordon Courtenay had been commissioned a lieutenant in the navy and had been assigned as chief surgeon on a warship, but the night before his ship was to sail he was suddenly taken ill. He had contracted the disease from ‘bluejackets’ he had been treating in Boston and died in Brooklyn on September 20.

The city board of health issued a bulletin on October 2 stating that the present pandemic seemed to exhibit an unusual virulence and that the gravity of the situation on the eastern seaboard had prompted the board to adopt all measures at their command for its control on this coast. Accordingly, under section 2979 of the political code, influenza was made reportable and all physicians must report cases to the health department immediately. Although no influenza cases had yet been noted in the San Diego newspapers, the board of health moved on October 12 to forbid all public gatherings in San Diego by closing theatres, moving picture shows, schools, dance halls, churches and bath houses. The school board, theatre managers and ministers were said to be in support of the plan and no violations of the order were expected. It was believed that by preventing large bodies of people from congregating indoors all danger of the spread of influenza would soon be eliminated. The order did not affect saloons; the health office stated that ‘men do not congregate in saloons in large numbers’ and the order was to ‘discourage or prevent large gatherings, such as was held last night in the interest of the anti-single tax measure’. A request to hold outdoor church services in Balboa Park was also turned down and the state convention of the Elks in San Diego was cancelled.

By October 14 the health board restrictions were extended to prohibit public funerals; hereafter all burials would be private. High school football games were cancelled for two weeks. Fort Rosecrans and the navy flying school on North Island were put under quarantine. By then 63 cases of influenza, but only one death, had been reported to health authorities, who were optimistic that they would clean up the scourge and schools could reopen the next week. The optimism seemed misplaced, however. The next day’s report was that there had been three deaths and a total of 103 cases, which the Tribune noted were mostly of Mexicans or ‘people of small means’ who were apparently ignorant of the symptoms and made no effort to secure proper treatment. The health department also ordered reading rooms of the public library system to close. Libraries would remain open for books to be issued and returned but all windows in the library buildings would be open and every book returned from a household where a case of influenza had existed would be thoroughly fumigated before putting it back in circulation. The restrictions in place on crowding had one interesting side effect; the Tribune noted that October 16 was the greatest opening day for duck hunting in many years as the influenza quarantine bans about everything other than the healthful field sports.

On October 16 the Tribune reported that only 22 cases had been reported against 26 the day before and that the authorities now believed that the tide had turned and that within a very short time the malady would pass to such an extent that the quarantine could be lifted. However, further precautions were being taken including closing the public market where farmers sold their wares and requiring masks on employees of large stores. The next day, as the influenza situation did not improve, more drastic regulations were imposed. Every server to the public, including clerks, waiters and waitresses, barbers, and bartenders, must wear the gauze face mask. Spectators would be excluded from trials. 56 new cases and 2 deaths were reported, including 4 cases from the navy training camp at Balboa Park. With 212 cases and 10 deaths so far, new regulations were laid down by the board; gatherings of a purely social nature, such as bridge parties, were ‘absolutely taboo’.

As the number of influenza cases grew, existing medical facilities were overwhelmed, and on October 19 it was reported that the Fremont school in Old Town was being made into a temporary receiving hospital. Desks were being removed and the rooms were being overhauled under the direction of the Red Cross. The new hospital would be for receiving and treating influenza patients and would have a capacity of 80 beds. It would be operated under the direction of E. Chartres-Martin, city health officer, assisted by a corps of volunteer physicians and surgeons. When the Fremont hospital opened on October 21 the Tribune reported that it would be designated an isolation hospital and that all influenza cases were to be isolated and treated there with a view to preventing further spread. Meanwhile, the health board reported that the number of new cases had been ‘almost stationary’ over the last several days, with daily totals in the 40s, which suggested that the outbreak would soon be curbed. Still, the board would take steps to strictly enforce precautions to prevent further spread of the malady, particularly the wearing of face masks would be insisted on and enforced, in spite of criticism.

The face mask order took effect on October 26, 1918, and required every individual in any office or place of business where he or she came into contact with the public to wear a gauze face mask. However, with 55 new cases and four deaths, the progress of the disease showed no signs of let-up and the health board urged citizens to continue to take every precaution to combat the disease. One of the new cases was the city health officer, Dr. Chartres-Martin, although his attack was considered mild and he was considerably improved by October 28. When the health department made public figures on October 30 showing 61 new cases of Spanish influenza, the increase was laid almost entirely to growing laxity in the use of the gauze masks. The department warned that unless every preventive measure was carried out, including wearing masks, no effort could be made to lift the quarantine at the different army camps. At Camp Kearny, 36 new cases of influenza were counted, as well as 21 cases of pneumonia and four deaths. There were 750 cases in the base hospital and the total number of influenza cases in camp since the epidemic began was 3242. There had been a total of 50 deaths.

The influenza epidemic continued its spread both at Camp Kearny and in San Diego in the first week of November. In camp on November 9 50 new influenza cases were taken to the base hospital and there were six deaths, making a total of 3404 cases and 64 deaths. In San Diego on November 12 there were 57 new cases and one death. However, Dr. Chartres-Martin did not consider the sudden rise in the number of cases to indicate that the influenza had returned to the epidemic state; ‘On the contrary, that stage has passed and we have now to deal with cases of mild form which will soon be cleared up’. The quarantine which had closed theatres, churches and schools was set to be lifted on November 18 and Dr. Chartres-Martin maintained that the situation did not warrant its extension. Public schools would remain closed, however, since state law apparently prohibited opening any public schools unless all were opened and the Fremont school was still being used as a hospital from which the 40 or more patients could not be moved. Health authorities had begun fitting and furnishing the office and bottling building of the recently closed Mission Brewery as an isolation hospital for 100 influenza patients and when the building was ready patients at the Fremont school would be moved and schools could be reopened.

Although regulations intended to prevent crowding were still in effect on November 11, news of the armistice ending World War I brought out the largest crowds ever seen in San Diego to that time. According to the San Diego Union, men, women and children, hundreds of them in scant attire, rushed from their homes breathlessly to read the tidings that victory had rewarded the Allied arms. Celebrations continued through the long, exquisite day and far into the night as humanity poured into the streets in innumerable streams, lighted by faces radiant with happiness long deferred. Thousands of homes gave forth their precious occupants, who gravitated to the business section. Aged and stooped men and women and dignified professional men strode the sidewalks shoulder to shoulder with men who wore marks of hard toil. In the afternoon the crowds lined the curbs to cheer units of army, navy and marines marching down Broadway in a hastily organized parade. An official parade was scheduled for November 15 and the Evening Tribune noted the although the flu had prevented other big mass meetings it would not affect this celebratory parade and carnival. However, an accompanying sports carnival was postponed until the Thanksgiving holiday ‘when the flu bans shall be lifted’.

The ‘flu bans’ were lifted on November 18 and by November 23 the local papers were reporting that San Diego was facing the worst week since the outbreak of the disease in early October, with 61 new cases and 4 deaths reported in each of the previous two days and 91 new cases and three deaths the day before that. The authorities did not offer an explanation for the increases but the Union noted that in some circles it was believed due to the termination of the quarantine and in others to several days of rainy weather the previous week. With 70 more new cases and three deaths the next day the authorities suggested that the increases may have been partly explained by the fact that doctors had only recently been making complete reports. Perhaps it would have seemed unpatriotic to suggest that the victory parades could have contributed to the surge of new cases after November 11.

That the epidemic had taken a ‘somewhat alarming course’ was borne out by figures made public November 26, which showed 73 new cases and three deaths the day before, a Monday, and a total of 115 over the preceding weekend. In the six days between November 19 and 25 there were 27 deaths while total deaths from October 31 to November 18 had only been 24. The disease was also spreading geographically, having left the bayfront and the ‘Mexican quarter’, and was breaking out in the ‘better residential sections’. The cases were also of a more serious form than those previously encountered. The idea was advanced that the situation might justify drastic corrective measures; a revival of the quarantine had been hinted at unofficially. Dr. Chartres-Martin said he would urgently request all churches which used the sacramental cup to dispense with it in their services for the present. Meanwhile the health department had practically vacated the Fremont school in favor of the new emergency isolation ward at the old Mission Brewery.

With influenza conditions having taken such a serious turn, plans to reopen the public schools were abandoned. By November 30, with conditions continuing to deteriorate, the health board announced that the quarantine, lifted less than two weeks earlier, would be put into effect again, affecting theatres, churches and other places where crowds gather. When theatre owners announced that they would refuse to comply, and questioned the health board’s authority to enforce the order, the city council met and passed a city ordinance to establish a quarantine, although it didn’t go into effect until December 6 and was limited to four days. Meanwhile, at Camp Kearny, the influenza situation appeared to have stabilized at about 50 new cases a day despite the general liberty granted during the week of Thanksgiving when thousands of soldiers, practically the entire command, mingled with the populace at Los Angeles and San Diego. The new cases were said to be mild and no changes were contemplated in quarantine regulations.

The reintroduction of the quarantine in San Diego on December 6 went smoothly; even the Theatrical Managers Association had a change of heart and voted to lend the health department every assistance in stamping out the epidemic, even offering the services of one man from each theatre each day to assist the board. Most stores were closed and the business district was almost deserted. The San Diego Union reported that there were many minor violations but no arrests, although the police announced that they would not be so lenient in the future. That future soon arrived, with the Tribune reporting on December 9 that the one place in San Diego that had drawn crowds despite the influenza epidemic was police court. The judge entertained representatives from practically every walk of life – ‘Chinese, merchants, white men and women, negroes, the rich, the poor, druggists, trash collectors, chauffeurs, clerks, all sorts’ – and sent them away $5 poorer in most cases and ‘with an abiding desire to live up in the future to every single influenza law’. The judge handled about 100 of the 300 arrests and the ‘court coin box’ was enriched by about $500. According to the Tribune the outstanding feature of the campaign against those who refused to wear masks was that those individuals were fast disappearing. Mask wearing had become ‘almost general’ among those who entered stores or did business with the public.

When the strict quarantine measures introduced on December 6 expired after December 9 the council adopted a new ordinance effective for another nine days making the wearing of the gauze mask obligatory in all places but the home. The mask should be made from at least four ply surgical gauze, or six ply cheese cloth, or preferably, from at least three ply butter cloth. A person was permitted to remove the mask when eating or if it would render the wearer physically unable to perform his occupation, or while receiving the sacrament. By December 11 the Union reported that San Diegans had faced the ordeal of the gauze mask and grinned and bore it. Whither one looked he saw masks which concealed all vestige of visage but smiling, twinkling eyes. Men, women and little children, even the newsboys running through the streets ‘wore ‘em’. Even the councilmen at city hall were at their desks, masked. On December 12 the news was of an abrupt drop of 64 in the new cases, to 115 yesterday from 179 the day before, the lowest total in 10 days. Authorities were unwilling to say if the sudden drop was due to the enforced wearing of gauze masks or was a product of the recent four-day ban on all business, but it was expected that churches would remain closed.

Over the next few days the number of new cases was substantially lower, in the 20s, and health authorities ventured to say that the epidemic in San Diego was on its last legs. Only two deaths were reported. The emergency hospitals were not so crowded. The authorities were not prepared to say whether the universal wearing of masks was responsible; bright sunshine weather might also have been a factor. At Camp Kearny the influenza conditions also showed continued improvement, with only 11 new cases and one death reported on December 12. The Sunshine and Kearny theatres at the camp would be permitted to reopen, the only exception to the regular order being that patrons must wear gauze masks. By December 16 the Tribune reported that authorities were of the opinion that the decrease in cases and fatalities which began with the adoption of the universal gauze mask ordinance had continued. Only 13 cases had been reported the day before, including two admitted to the old Mission Brewery. Each day showed a wonderful improvement of the situation and led health officials to believe that the epidemic may be entirely stamped out. The continuation of the most rigid precautions, however, was urged. On December 18 only 29 new cases were reported, which the Union claimed was the smallest for any one week day since the outbreak of the epidemic in San Diego. The number of cases was a decrease of 150 compared with December 10, when the universal wearing of the face masks was made compulsory, there being 173 cases that day. Although the face mask ordinance was due to expire on December 18 the council extended if for another week, to December 24.

In the final weeks of 1918 influenza cases in San Diego continued to decline. New cases on December 19 numbered 21, the lowest figure in weeks. Better still, 10 of the cases were in houses where the disease already existed, evidence that it was not spreading except where there had been direct exposure. The wearing of masks since that method of precaution was adopted was given full credit. On December 20 only 9 cases were reported in San Diego. In Camp Kearny, only four cases were reported, and one death. The last previous date on which this low number was reached was October 10. The total since September 25, when the scourge began, was 4654 cases and 145 deaths at the camp.

By December 27 the news was even better. In San Diego only one new case of influenza was reported, making six cases since Christmas eve. For the last five days only 25 cases had been reported, equaling the total number of cases for one day on December 17, when the decline began, and by December 30 the health board was anticipating an early end of the epidemic. On January 1, 1919, the Union claimed that influenza nearly made an exit for the New Year, with only eight new cases and no deaths reported on New Year’s Eve. Schools would reopen on January 6. On January 2 Camp Kearny reported that after a ‘flare-up’ on December 31 new cases fell from 13 that day to five, and one death, the first in nine days.

Influenza did not make an exit for the new year; new cases of influenza, and deaths, continued to be reported in the first weeks of 1919. On January 7, 12 new cases were reported, nearly all young persons, under 40 years old. There had been 12 deaths in the year so far, an average of 2 a day. Readers in San Diego were also informed of notable cases outside of their city. Walter Johnson, pitcher for the Washington Senators (and future Baseball Hall of Famer), had been seriously ill for two weeks with the influenza but was recovering rapidly at his farm in Kansas. Mary Pickford, noted film star, was suffering from Spanish influenza but was also considerably improved, although still confined to her bed at home with two nurses in attendance. The Evening Tribune also claimed that although there had been 20 new cases and three deaths over the last few days, San Diego was favored in mildness of the epidemic compared to Los Angeles, where there were 600 to 700 new cases reported daily. Every effort was being made to prevent importations of flu cases from that city. By January 12, with 24 new cases, four fewer that the previous day, and two deaths, the Union reported that with further improvements being shown in the influenza situation the board of health had made no further effort to adopt another face mask ordinance nor did it order the schools closed.

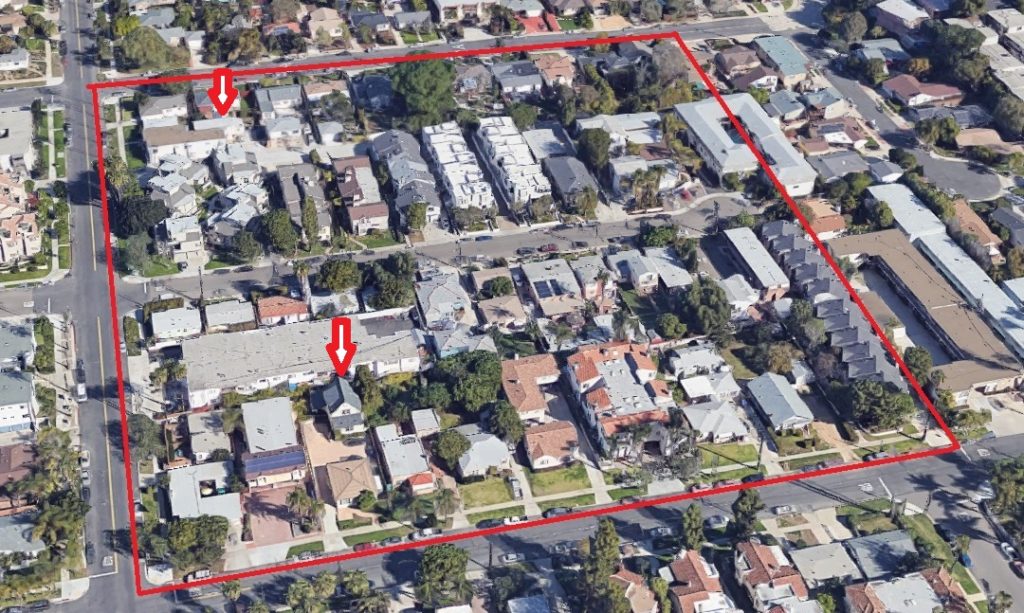

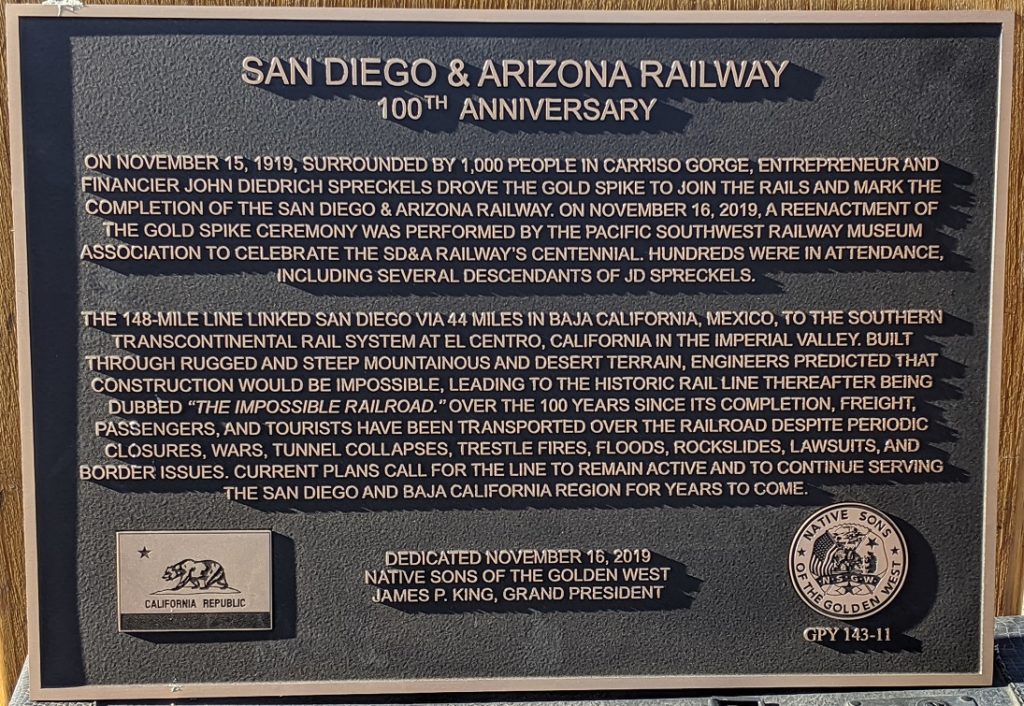

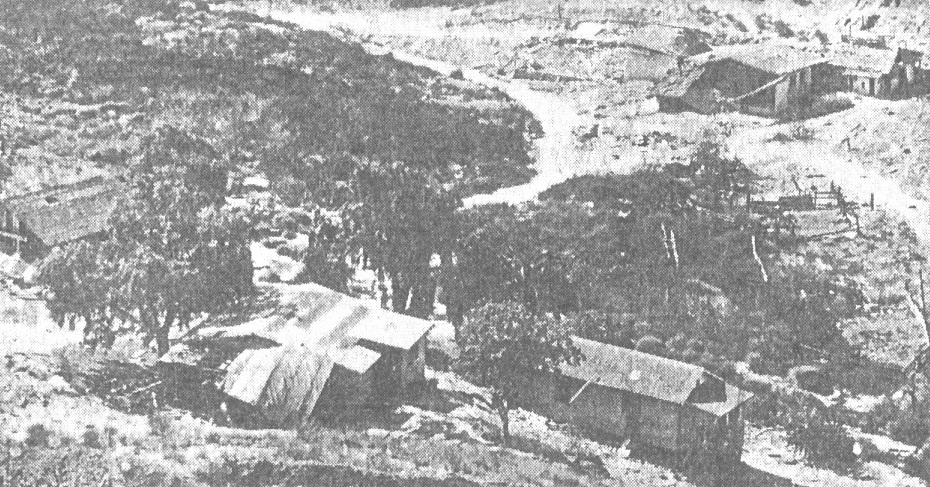

The influenza epidemic in and around San Diego affected local affairs beyond theatres, churches and schools. San Diego’s highly anticipated direct rail connection to the east, the San Diego & Arizona Railway, had been under construction since 1907 and by the end of 1918 the work had reached its final and most challenging phase, blasting tunnels out of solid rock in Carrizo Gorge in eastern San Diego County. However, work camps in the gorge proved to be ideal incubators for influenza and 215 cases and 28 deaths had been reported among the crew of about 350 men, seriously impacting construction work. By the middle of January 1919, however, the railroad was able to report that influenza had been eradicated in the gorge and labor conditions had become more settled. Excellent progress was reported on tunnel work and everything seemed favorable for completion of the line (a ceremonial golden spike was driven in Carrizo Gorge to complete the line in November 1919). In sports, the San Diego High School football team advanced to the league championship game because six players on the Pomona team, which had earlier beaten the ‘Hilltoppers’, were ‘out of the game’ with influenza and Pomona was forced to forfeit its final game against Fullerton (Fullerton went on to beat San Diego in the championship game).

By the end of January 1919 the Union was reporting that influenza was at a low ebb, only about five new cases a day, better than at any time since the disease first broke out in this city. Each day saw fewer cases and the authorities predicted that the disease would entirely disappear soon. No deaths had been reported in a week. While conditions were slightly improved in Los Angeles they were still bad, around 100 a day. At Camp Kearny, the number of new cases was also the lowest since the epidemic began; only about one a day. It had also been weeks since any deaths were reported at the camp.

The influenza situation continued to improve in February. On February 6 the Union reported that the hospitals were nearly empty and there were few ‘quarantines’; homes where influenza had been reported and the residents were forbidden to leave. On the 9th, Camp Kearny reported that there had been two days which ‘scored zeroes in the three columns in the base hospital report devoted to influenza, pneumonia and death from either of these’, and two consecutive days on which not a single new case of influenza was reported. In fact Camp Kearny had reported only seven new influenza cases, one pneumonia case and one death during the first half of the month. By the middle of the month influenza was also regarded as a ‘dead issue’ by San Diego health authorities; only one case being reported over the last several days. At the end of February there was a report of five new cases, the first in several days, but they appeared in only two families (the report in the Tribune included the families’ names and addresses).

Reporting on the influenza epidemic all but disappeared from local papers after February 1919. While there were still a few new cases they were described as mild and even fewer deaths were reported. By April the only news was the accounting of costs for the recent Spanish influenza epidemic; more than $20,000, due the American Red Cross for operation of the Fremont and Mission Brewery emergency hospitals, most of which was provided by the United States government for caring for sailors at the isolation hospitals.

Spanish influenza had probably arrived in San Diego by October 1918 and by the middle of that month its spread had prompted quarantines of Camp Kearny and other military camps in the area and the closing of schools, churches, theatres and other activities where people gathered in San Diego. Employees of businesses that served the public were required to wear face masks. Churches and theatres, but not schools, were reopened in mid-November when the levels of new cases had seemed to level off, but in early December a renewed rise in cases prompted a four-day total business shutdown followed by a three-week period when all residents were required to wear masks outside the home. Possibly as a result, the number of new cases began to subside around Christmas and schools were reopened in early January 1919. By mid-March the disease had essentially disappeared. It is estimated that nearly 5000 people were infected with the virus in San Diego and 366 deaths were blamed on it.

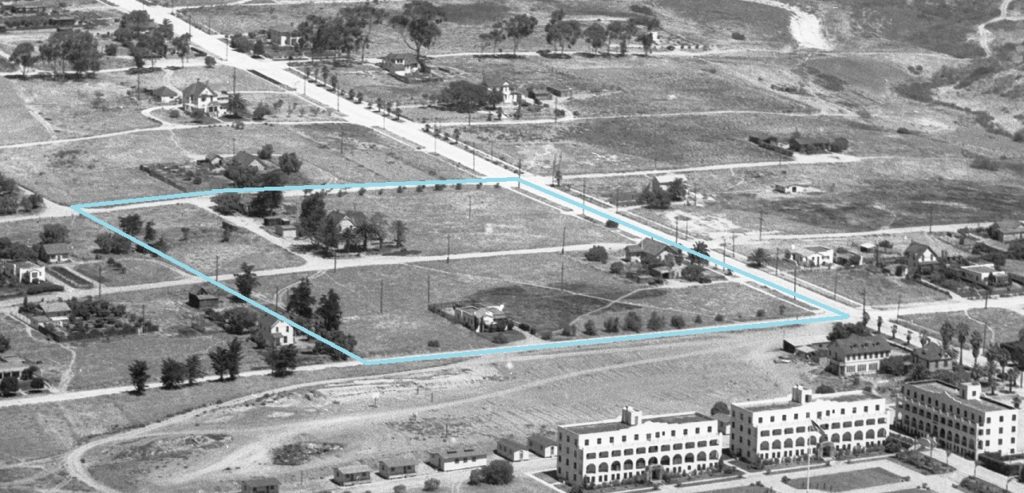

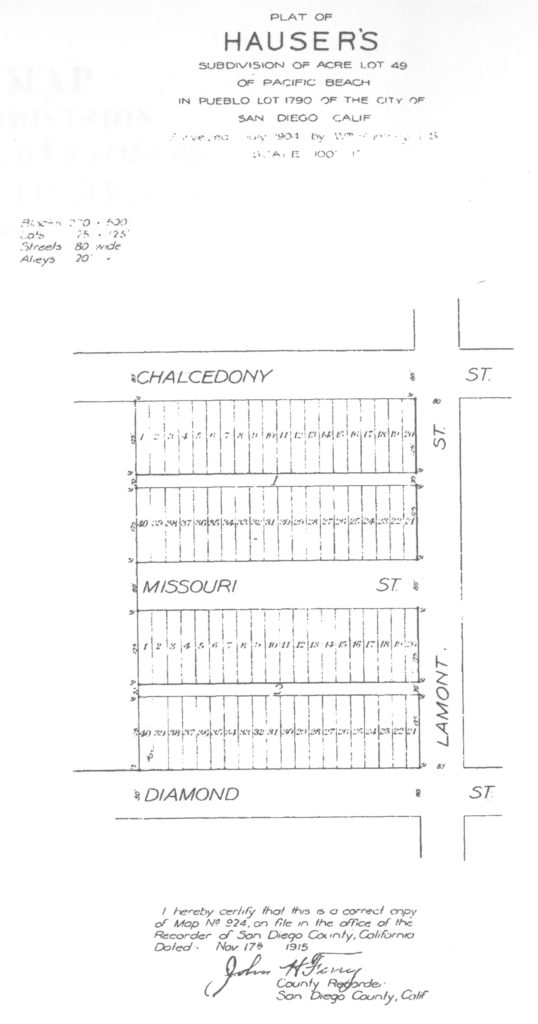

A few relics of the epidemic still exist in San Diego. Fremont Elementary school, on Congress Street in Old Town, reopened in 1919 and remained active until 2001, although most of the original school was torn down and rebuilt in 1948. It is now a school district training center, although like most other schools and offices it has presumably been closed again during the 2020 pandemic. The Mission Brewery, which had opened in 1913 but closed earlier in 1918 and was used as an isolation hospital for flu patients, reopened as a plant for producing agar from kelp in the early 1920s and operated intermittently until 1987. Now the Mission Brewery Plaza, it is still standing at West Washington and Hancock streets in Middletown and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.