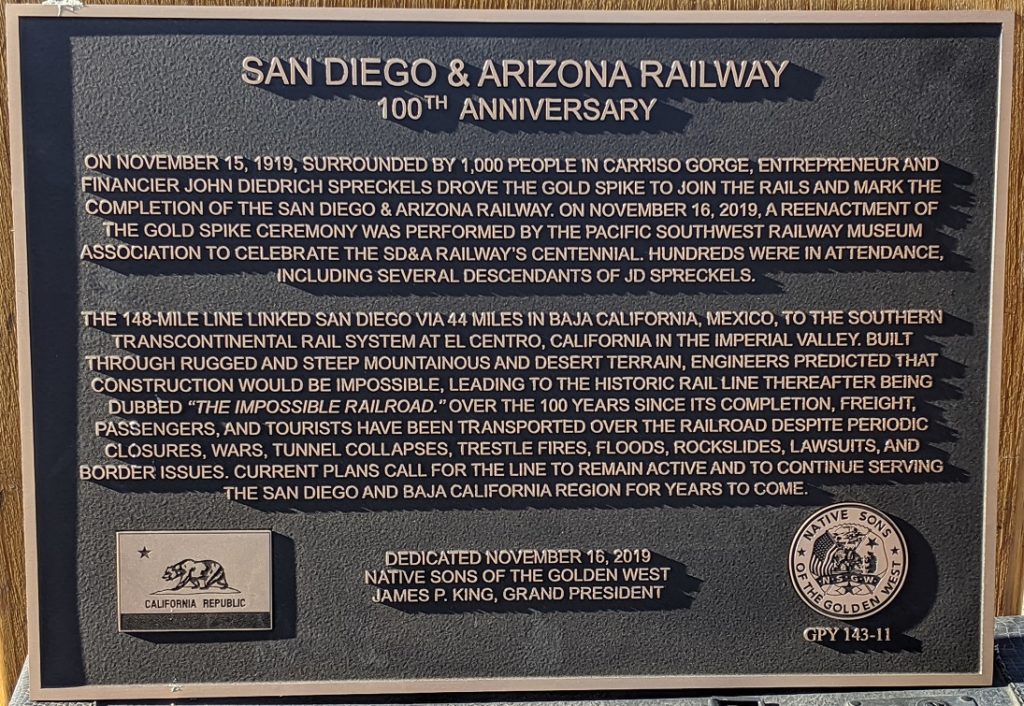

Last month the Pacific Southwest Railroad Museum staged a reenactment of what was considered the greatest event in the history of San Diego when it took place a century ago. On November 15, 1919, in a remote desert canyon, J. D. Spreckels, founder and president of the San Diego & Arizona Railroad, drove the golden spike that symbolized completion of a new rail line linking San Diego with the Imperial Valley and points east. Speakers impersonating the dignitaries who spoke at the original ceremony emphasized the difficulties involved in building the line, which had already become known as the ‘impossible railroad’, and praised Spreckels for his determination in leading the effort that finally overcame the many challenges – for doing the impossible.

Work on the SD & A had begun in 1907 but a number of difficulties, principally the challenging terrain along the planned route, had stretched construction out for over twelve years. The most challenging section of the route was in Carrizo Gorge, north of Jacumba, where for 11 miles the SD & A right-of-way was blasted out of a sheer canyon wall, requiring 17 tunnels totaling 2 ½ miles in length and 14 wood trestle bridges. In November 1919 construction crews laying track from both ends of Carrizo Gorge finally came together and Spreckels and a trainload of the city’s leading citizens congregated there to celebrate his triumph by driving in the last spike. However, the 2019 reenactment of this historic occasion did not occur at Carrizo Gorge, which has been closed to passenger rail service for nearly 70 years, but instead at a railway museum in Campo where railroad enthusiasts can still ride in vintage coaches with SD & A lettering over the few miles of the route that are still open. The audience was well aware that the reenactors’ tributes to Spreckels for doing the impossible were ironic, and that the railroad turned out to be impossible after all.

Passenger service over the new railroad line was inaugurated on December 1, 1919, but after only six weeks, in January 1920, the San Diego Union (which was also owned by Spreckels) reported that a rock slide, not large enough to do any ‘real damage’ but just large enough to prevent temporarily the passage of trains, occurred on the SD & A in Carrizo Gorge. The landslide was just west of Tunnel No. 13 and the railway stated that this particular point had been questionable for some time and dynamiting had been considered, so the slide actually relieved the company of this trouble. The Evening Tribune (also owned by Spreckels) added that although nature had ‘saved the powder’ the line was still blocked and passengers on the westbound train No. 3 and eastbound train No. 4, which had arrived at opposite ends of the slide, had to be ‘transported’ around the slide to the other train, which then reversed course and took them on to their destinations. Despite this inconvenience, the railway company emphasized that the track through Carrizo Gorge was becoming more settled each day and was in a very satisfactory condition, and there should be no trouble from this time on. This optimistic assessment was reinforced a month later, in February 1920, when the Union reported that rainfall in the mountain regions was heavy enough in Carrizo Gorge to put the new roadbed to the test that had been awaited by railroad officers. The many precipitous water courses that the rails passed over flowed strongly during the storm but since the many tunnels, cuts and trestles successfully withstood the forces of the first big storm no future trouble of any kind was looked for.

Future trouble occurred anyway, and it was of the kind that did cause real damage. The Union reported in May 1920 that a slide on the side of a mountain over tunnel No. 7 in Carrizo Gorge would probably put the San Diego & Arizona railway out of commission temporarily; although the tunnel was open and trains could be operated through it that was not considered advisable until the part that had given way was removed, which would require several days. Arrangements had been made to transfer passengers between Campo and El Centro by automobile. According to the railway this was the only tunnel through the gorge that had given trouble of any consequence. Two days later, however, the report was that a rift in the rock formation had caused a shift of a huge mass of rock and earth bearing down on the west end of tunnel No. 7. A section of the mountainside 590 feet long, 200 feet high and 200 feet wide at the west portal of the tunnel was unstable and was sliding downhill, crushing 128 feet of the tunnel and 480 feet of track leading to the tunnel. Blasting would be required to break down practically the entire side of the mountain. This would close down the line for a period of five weeks and cost the company approximately $250,000 but, on the plus side, would make impossible any recurrence of the trouble and make the tunnel absolutely safe for all time. A big steam shovel with a force of about 100 men was already at work on the west end of slide. Another shovel with its crew, based a few miles west of the slide, had started a roundabout trip of about 430 miles via Colton and El Centro in order to reach the east end of the slide.

Blasting off the side of the mountain required miners to sink three shafts 25 to 35 feet deep near the top of the slide and oil-drilling rigs to drill six holes 50 to 60 feet deep near the roadbed. These were filled with 50 to 60 tons of black powder and dynamite and in early June J. D. Spreckels himself made the trip to Carrizo Gorge by special train to throw the switch setting off the blast. According to the Evening Tribune, there followed a heavy roar with a concussion that rocked the ground. Vast clouds of dust were sent skyward and thousands of tons of rocks and boulders went hurtling and bounding into the canyon below. Good results were obtained, although not entirely up to expectations, and no accidents of any kind were recorded. A film crew was on hand when the big blast occurred and a few weeks later citizens of San Diego were able to watch it on the big screen; the ad in the Union read ‘Blown Up! A Whole Mountain to Make Carriso Gorge Safe on the S. D. & A. Railroad. See the Big Blast at the Cabrillo. Now — This Week.

However, debris from the Big Blast and a subsequent shot still had to be cleared away and the tunnel rebuilt and two months later the railroad reported that progress had been much slower than expected. Four steam shovels were working two full shifts and the obstruction had been cleared up to approximately 100 feet from the tunnel portal. The railroad predicted that the line should be handling traffic by the end of August and denied a statement in the Los Angeles Examiner that the blasts had been a complete fiasco since the many tons of earth and rock thrown clear of the roadbed had reduced the material to be handled by the steam shovels. The end of August came and went and in October the railroad announced that although the slide had been cleared and the roadbed widened it would still be necessary to drive 166 feet of new tunnel to connect with the present tunnel, possibly by mid-November. When the line did reopen on Thanksgiving Day after being closed for seven months an editorial in the Union declared that every possibility of future delay by reason of similar obstruction had been permanently removed and henceforward San Diego would serve as the Pacific terminal of a direct transcontinental railway.

Actually, other possibilities for delays still existed and in August 1921, less than a year later, the line was closed for several days after heavy and sudden rain hit the western side of Imperial Valley. The terrific downpour had caused 20 washouts along a stretch of about nine miles there leaving a much weakened roadbed in its path. After another storm in December 1921 good progress was reported on repairs to the SD & A roadbed at washed-out points between Tijuana and Carrizo Gorge, although several more days would be required to open the line to through traffic. Through service was restored early in January 1922 but trains were required to travel slowly over three of the washouts so the train making a connection with the Golden State at Yuma would have to leave San Diego an hour earlier than regularly scheduled (at Yuma a sleeper car from the SD & A train was switched to the Southern Pacific’s Los Angeles to Chicago Golden State Limited so that a passenger could go all the way from San Diego to Chicago in the same car). Closures of several days also occurred in December 1926 at the edge of Imperial Valley, February 1927 between San Diego and Tijuana, and September 1929, when 11 miles of track in Carrizo Gorge and 18 miles in the desert approach to the gorge had to be repaired after a cloudburst.

1932 turned out to be an even worse year for the SD & A. In January a fire was discovered in Tunnel No. 3, located south of the Mexican border between Tecate and Campo. Heavy smoke and heat from the flames prevented fire crews from entering and the railroad announced that all traffic would be diverted through Los Angeles until the fire burned itself out, possibly after several days. When the fire had burned out and the tunnel cooled crews began removing debris and installing new timbers, around 1,500,000 board feet of redwood, which had arrived by ship from Northern California. One shipment of nearly 1,000,000 feet from Fort Bragg, including huge squared balks of redwood, four-by-sixes and planking, was unloaded at Pier 1 in San Diego and taken to the tunnel on 50 flat cars. Tunnel No. 3 had originally been 1296 feet long but a section near the east end had collapsed as a result of the fire, ‘daylighting’ that section and dividing the tunnel into two sections, to be named Tunnels No. 3 and 3 ½. Crews finished retimbering the tunnels at the beginning of March 1932 and service was resumed after six weeks and an estimated cost of $100,000, not counting loss of revenue.

In late March 1932, three weeks after the line was reopened at Tunnel No. 3, a slide apparently due to heavy mountain rains blocked the line of the SD & A at the east portal of Tunnel No. 15 in Carrizo Gorge and traffic was again rerouted through Los Angeles. Although the initial report was that the trouble was temporary and service would soon be resumed, the mountain continued to slide and it became apparent that Tunnel No. 15 could not be repaired and the tracks would have to be realigned around it. The realignment would include a new, shorter Tunnel No. 15 and a curved trestle bridge 633 feet long and 185 feet above the canyon floor. The trestle was also built of redwood and is said by some to be the largest curved wood trestle in the world. It is certainly spectacular and has since become a symbol of the SD & A line.

Construction work on the Tunnel No. 15 realignment was completed and the line reopened in early July. However, in October 1932 the railroad experienced another tunnel fire, this time in Tunnel No. 7 in Carrizo Gorge, the same tunnel that had caused problems in 1920. Again there was no possibility of fighting the fire and instead both entrances to the tunnel were sealed in an effort to snuff it out, and traffic was rerouted through Los Angeles. Once the fire had burned out and the tunnel cooled enough for inspection, railroad officials determined that it too was beyond repair and would have to be abandoned. The roadbed was realigned in a series of sharp curves 2200 feet long that bypassed the abandoned tunnel and the line reopened in January 1933 after having been closed for more than half of 1932.

J. D. Spreckels had founded and initially owned the SD & A but had required financial support from the Southern Pacific railroad for its construction. In 1916 the Southern Pacific recovered a portion of this outlay by taking a half-interest in the SD & A. Spreckels died in 1926 and in 1932 his estate’s remaining half-interest was also acquired by the Southern Pacific. While wholly owned by the Southern Pacific, the railroad was operated as a separate unit and renamed the San Diego & Arizona Eastern Railway, or SD & AE. The sale was finalized in February 1933 and the SD & AE operated relatively successfully for a number of years thereafter, particularly during the war years of the early 1940s when there was a heavy flow of materiel and military personnel to the port and military bases around San Diego. However, more people were driving cars and more and better highways were being built, including US Route 80 which duplicated the route of the SD & AE between San Diego, the Imperial Valley and the east. Commercial aviation was also improving and attracting growing numbers of passengers. In the years after the end of the war in 1945 traffic on the SD & AE declined and in 1952 passenger service was abandoned.

Freight service continued, although not without incident, especially in Carrizo Gorge, where the rough road and sharp curves made the line prone to derailments. One particularly memorable derailment occurred in May 1965 and closed the line for several days. According to the San Diego Union, one car loaded with wine from New York state was destroyed to prevent looting and two truck trailers with 72,000 cans of beer slid from a flat car 600 feet into Carrizo Gorge (in the following months 24 persons were apprehended in quest of free beer).

In September 1976 tropical storm Kathleen drenched San Diego’s east county and the Union reported that a torrent of water ripped through Carrizo Gorge to destroy portions of three bridges supporting the SD & AE railway. Two trains had been turned back and it would be at least two weeks before rail service was restored. In fact service was not restored until December 1982, over six years later. In the meantime the Southern Pacific sold the railway to San Diego’s Metropolitan Transit Development Board which wanted the SD & AE’s suburban rights of way for the light rail system that became the San Diego Trolley. One of the conditions of sale was that the Southern Pacific had to restore the line to service, but just a week after service was restored another storm dropped 2 inches of rain on the desert approach to Carrizo Gorge near Ocotillo and blocked the route again with tons of rocks and landslides. Six months after that damage was cleared a brush fire in June 1983 burned two trestles and threatened a tunnel in Carrizo Gorge. Although the tunnel did not sustain serious damage, the trestles were destroyed. Fires in tunnels No. 16 in 1986 and No. 8 in 1988 further damaged the line in Carrizo Gorge and Tunnel No. 3 in Mexico caught fire again in 1999. This damage was eventually patched up (Tunnel No. 3 was ‘daylighted’) and the line was open for occasional freight service between 2004 and 2008, but it is now inactive except for the short excursions around Campo. The ‘impossible railroad’ still has its boosters, however, and J. D. Spreckels would have been proud to hear one of the speakers at the centennial celebration declare that the line would be open again next year.