Everyone has heard of San Francisco’s cable cars. Twenty-three cable car lines were built there between 1873 and 1890 and three are still in operation today, the last cable car system in the world and a major tourist attraction for the hilly city. Fewer people know that San Diego also had a cable car line in the nineteenth century. It only ran for a couple of years and was tainted by scandal.

The completion of a transcontinental rail line in 1885 had created a ‘boom’ in the city’s population and the resulting spread in the populated area created a demand for public transportation. In 1886 the San Diego Street Car Company laid three miles of tracks on D Street (now Broadway) and Fifth Street (now Avenue) in the downtown area and began operations with horse-drawn cars. However, some of the new residents had moved to homes on the mesa north of downtown, an area then known as Florence Heights, and real estate operators were preparing to open additions even further to the north, like College Hill and University Heights. A street car line using horse power over these distances would be impractical and the use of steam engines was generally not allowed on street railways.

One alternative form of motive power that was just coming into existence at the time was electricity. The first practical electric motors capable of powering vehicles had been introduced in the early 1880s and by the mid-1880s systems were being developed to adapt electric power to street railways. In February 1887 the Electric Rapid Transit Street Car Company was formed in San Diego. The Electric Rapid Transit company intended to utilize a system patented by J. C. Henry on a line from the foot of Fourth Street to Florence Heights, continuing to University Heights along Fifth Street. In the Henry system electricity supplied by a central dynamo was delivered through wires strung above the tracks and picked up by a ‘troller’, a device that pinched the wire between grooved wheels and was towed by a cable that connected it to car’s electric motor.

The Electric Rapid Transit Fourth Street line went into operation in January 1888. According to the San Diego Union, two trains were run between H (now Market) and Upas streets in seven minutes. They were reportedly capable of performance that had seemed inconceivable at the time, climbing and even stopping and starting on an 8 or 9 percent grade. However, some passengers were concerned that the great sparks flying from under the wheels, some of which were as brilliant as an electric light, made riding the cars seem like ‘fooling with dynamite’. Dr. Gochenauer, the president of the company, reassured the passengers that the sparks were caused by burning rust and dirt and would disappear when the rails had become polished. He also reassured passengers that fine watches would not be injured by the intense magnetism radiated from the motor.

Dr. Gochenauer resigned in March, 1888, stating that the system had reached a state of perfection and was in complete running order and that he was leaving so he could introduce the Henry system of street car propulsion to other California cities. Trains were making trips every ten minutes from Steamship Wharf to Florence Heights and hourly trips from Florence Heights to University Heights. However, the street car traveling public had apparently not been entirely convinced by Dr. Gochensuer’s reassurances and the Union reported that in future a coach would be attached to each electric motor car, thereby giving an option to the many possessed by the idea that ‘to ride on an electric motor is to ruin your watch’. By the end of 1888 the company had four cars running from the foot of Fifth Street to Laurel Street and was expecting to run an additional car every half hour from Laurel to University Heights, making fifteen miles an hour.

Despite the many positive reports on the merits of the electric street cars, however, the Electric Rapid Transit company was not a commercial success. The new electric system was one of the first to be deployed anywhere and the technology was not yet entirely reliable. There were frequent breakdowns and service interruptions and in the summer of 1888 the whole system shut down for six weeks for alterations and repairs. In April 1889 new president George D. Copeland asked the city council to amend his company’s franchise to allow it to use motive power other than electricity or horses. In a conversation with the Union, Mr. Copeland revealed that his preference was for a cable railway. Operation of the electric railway had ceased by the summer of 1889 and in July the wires and poles on Fourth, Fifth and G streets were removed; apparently boys were in the habit of throwing stones at the wire on Fourth Street, making a very unpleasant noise and causing ladies to avoid that street for fear of frightening their horses.

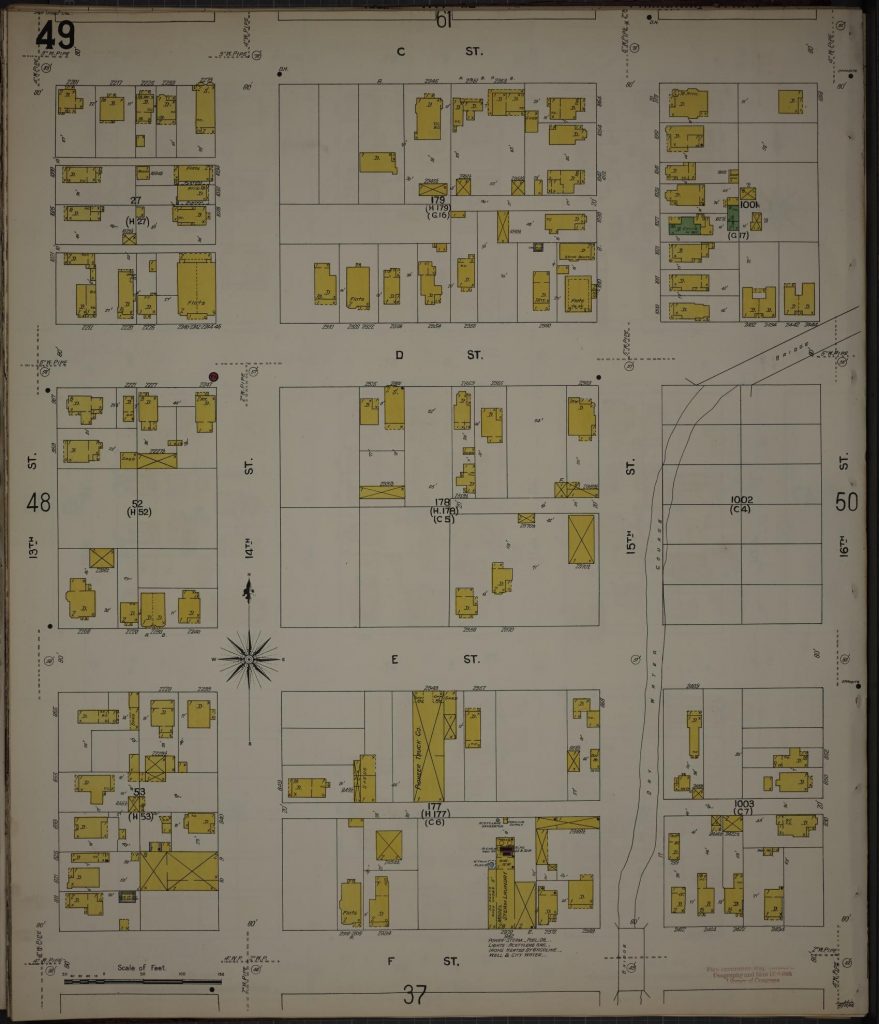

In June 1889 another group of prominent citizens and property owners initiated a competing proposal for a cable line along Fourth Street from the waterfront to University Heights. When they learned that downtown businesses and residents of Sixth Street would subscribe substantially more money toward construction of the line than those of Fourth Street, the proposed route was altered to run from the foot of Sixth Street to C Street, then on C Street to Fourth, where it would continue north. The San Diego Cable Railway Company was given an ‘official and legal birth’ in August 1889 when articles of incorporation were filed listing D. D. Dare as president, John C. Fisher as vice-president and J. W. Collins as secretary and treasurer. At a council meeting in September the city awarded the Cable Railway company a franchise to build and operate a cable line.

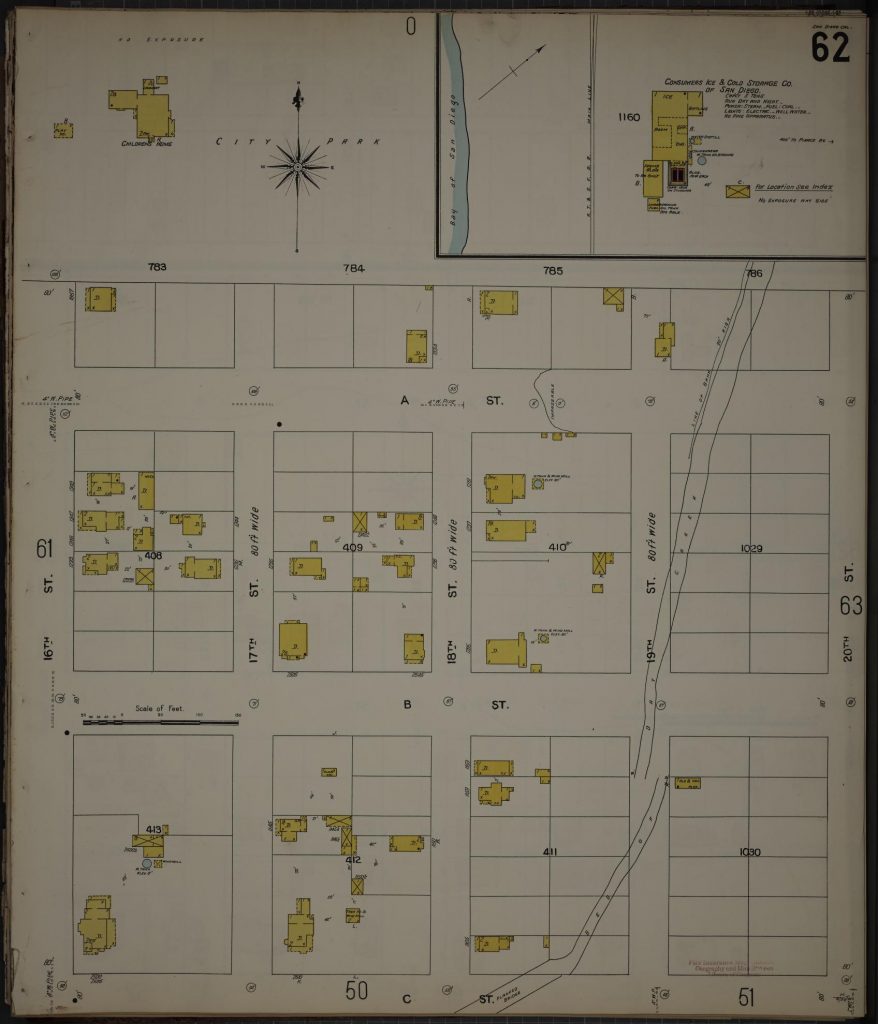

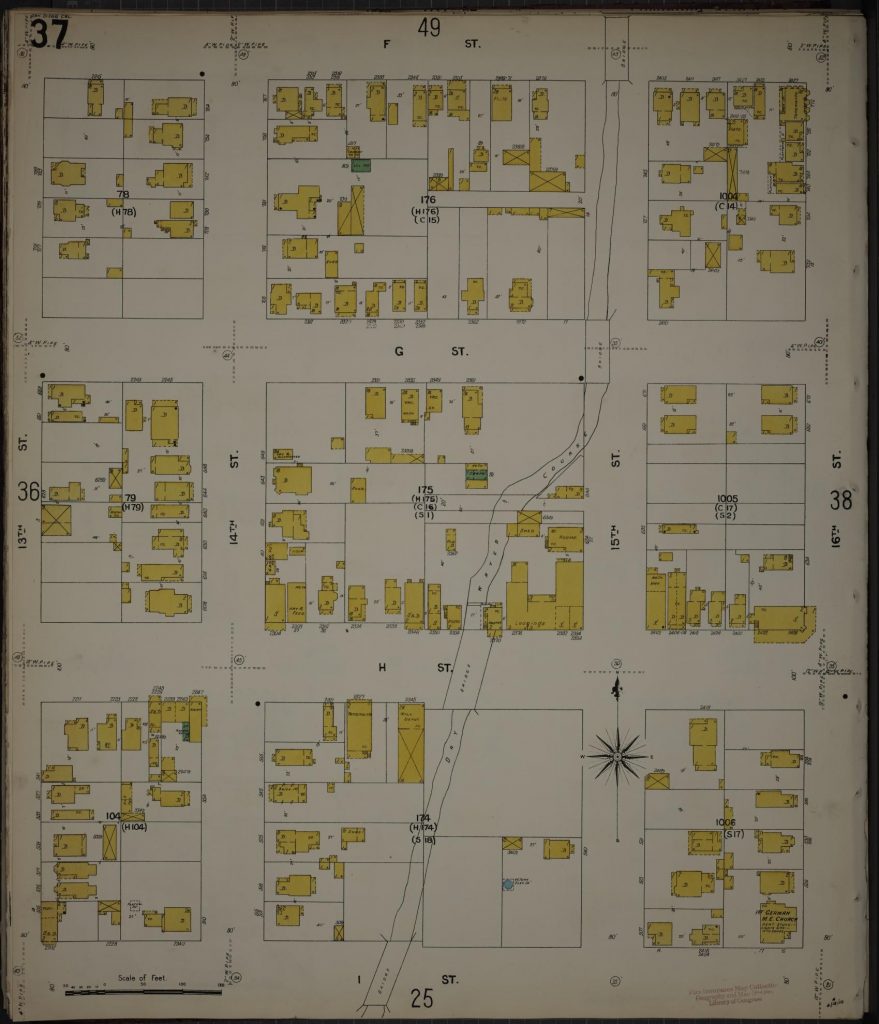

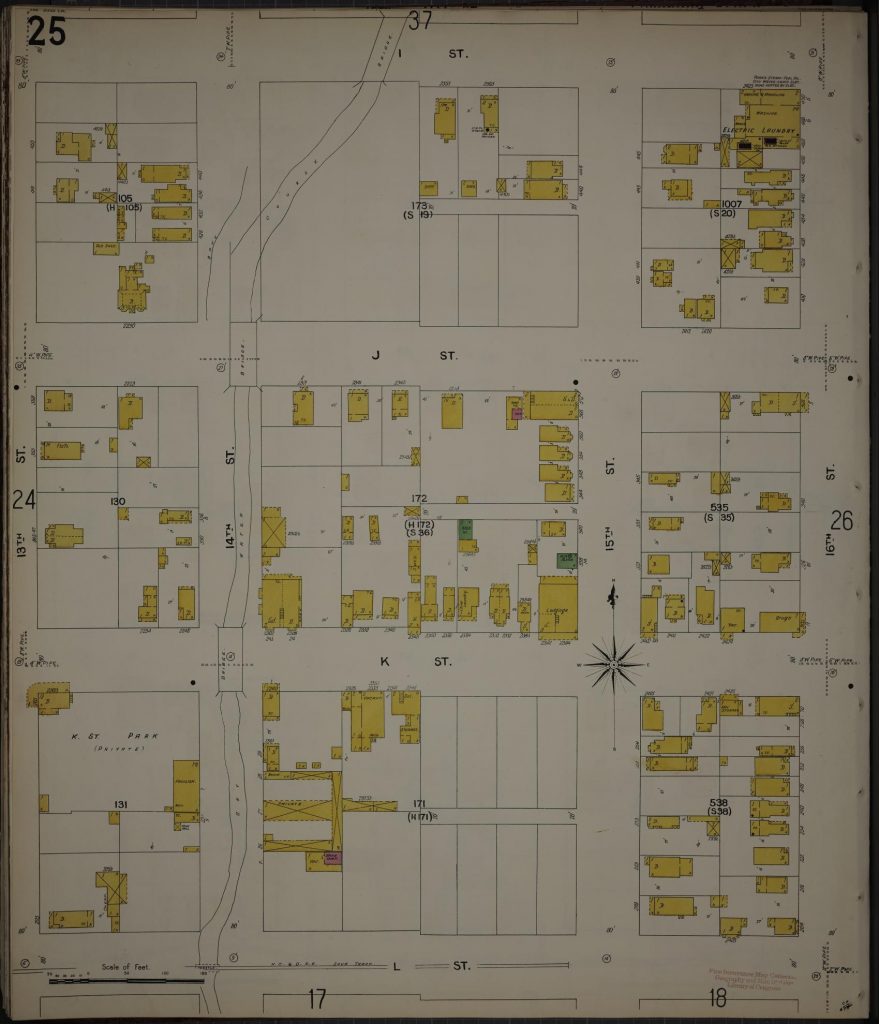

In a cable railway, cable cars connect to a continuously moving miles-long loop of cable in a conduit under the streets powered by an engine in a central power house. The connection, called a grip, extends beneath the floor of the car into a slot between the rails and enables the operator of a cable car, the gripman, to grip the moving cable to put the car in motion or release it to come to a stop. The San Diego Cable Railway was built in two sections which met in front of a power house at Fourth and Spruce streets. The lower or ‘town’ section was about two miles in length and would follow the route favored by the Sixth Street subscribers, on Fourth Street between the power house and C, then on C to Sixth, and on Sixth to K. The upper or ‘mesa’ section ran about three miles between the power house and a park to be built overlooking Mission Valley, following Fourth to University, then on what are now Normal Street and Park Boulevard to the terminus. The line was single track with occasional turnouts to allow cars going in opposite directions to pass. Turntables were built at each end of the line to turn the cars around and in front of the power house to transfer cars to and from a section of track that led inside, where they were stored when not in use. The rails were a narrow three foot six inch gauge and were laid on cast iron yokes, which formed the conduit beneath the rails for the moving cable. The two sections had separate cables, continuous loops which ran from inside the power house out to the main line on Fourth Street, where they were diverted under the lower or upper section by pulleys. There were also pulleys under turns and at the ends of the lines. Within the conduit the cable ran in both directions under the single track line; at the turnouts the cables moving in different directions split to follow one of the branches. The cable for the lower section was designed to move at eight miles per hour; the upper cable moved at ten MPH. The two cables totaled 52,000 feet in length. They were initially laid in the conduit by attaching the cable to a grip in a car and drawing the car along the line with a team of about a dozen horses.

On April 11, 1890, the Union reported that Vice President Fisher had applied the match to the fuel in the furnaces and soon the hissing of steam gave a decidedly business-like sound to the affairs at the power house at the corner of Fourth and Spruce streets. Workmen began their lunch to the melodious sound of a powerful whistle. The power house was a solid brick structure occupying 100 feet on Fourth Street, 200 feet on Spruce Street and 40 feet on Third Street. The engine room was on the Spruce Street side, where two immense Corliss steam engines powered the cable-driving apparatus, most of which, including the huge driving wheel, was manufactured at the Coronado foundry.

The cable cars were ‘things of beauty’, with both an open and closed compartment for passengers. The gripman’s platform was in the center of the open end, with a bench for passengers on each side and shorter seats in front facing the track (the open end apparently served as the smoking section). The closed portion of the car was beautifully finished in rare woods, with stained glass transoms along the top, richly curtained windows and nickel-plated metal work. Best of all, electric bells were provided by which passengers could notify the gripman to stop the car without leaving their seats. They were ‘gorgeous little palaces on wheels’, the handsomest in the world. The outside of each car was beautifully finished in rich colors with gold lettering. The cars were numbered and named: 1, Montezuma; 2, El Escondido; 3, Los Penasquitas; 4, La Jolla; 5, Alvarado; 6, Cuyamaca; 7, San Ysidora; 8, San Juan Capistrano; 9, Tia Juana; 10, El Cajon; 11, Point Loma; 12, Los Flores.

The section of the line between downtown and the power house was completed first and a grand opening was held on June 7, 1890. The cars, with No. 2, El Escondido in the lead, were run out over the turntable at the entrance to the power house and on to the line, where the grip-end was festooned with a large flag, palm fronds and flowers by members of the Ladies’ Annex of the Chamber of Commerce. At 10:00 o’clock the gripman ‘put on the grip’ and the car started down from the heights; ‘for San Diego a car of progress of weightier consequences than any which had ever gladdened her vision’. All along the line people ran to their doors and windows and gates, waving and shouting and waving flags. The foot of Sixth Street was reached in just 22 minutes. The car was turned on the turntable and on the way back it filled up rapidly for the hill climb.

A ceremony featuring the City Guard Band, city officials and other dignitaries was held in the afternoon at the power house, which had been draped in bunting for the occasion. Among the speakers was Rose Hartwick Thorpe, the world famous author of the poem Curfew Must Not Ring Tonight, then a resident of Pacific Beach, who read an original poem, The Maiden by the Sea, written for the day. An original song composed by Philip Morse was sung and received the ‘loudest possible marks of appreciation’:

All cheer to the men whose enterprise and zeal

Have given us this splendid cable line

With Collins, Dare and Fisher and likewise Haversale

Our city will soon all other outshine,

With the chorus:

Then let the big wheel turn that hauls the cable round

And everyone will make the trial trip

And over all the world the chorus shall sound

For San Diegans never lose their grip.

The second section of the cable line, the upper or mesa section, was completed In July 1890. It ran north from Fourth and Spruce to a park, pavilion and recreation grounds on a hill overlooking Mission Valley. Cars ran every ten minutes and the fare was five cents.

One of the reasons for building street railways was to attract commerce and residents to the areas accessed by the lines, and property along the line of the cable railway was no exception. Real estate operators offered deals on lots along Fourth Street and in the new subdivisions near the northern terminus. The cable company also developed property it owned along the line, including a new baseball field, Recreation Park, at Fourth and A streets. The Union reported in August 1890 that the San Diegos and the Schillers and Murthas would play a match game of ball in the new ball park on the line of the cable railway. The grounds were 350 by 400 feet and the boys had been practicing every day for the past three weeks so all interested in the welfare of the national game should turn out strong for the opening game on Sunday. The baseball season opened in October and the Union announced that ladies would be admitted free at Recreation Park on the cable line. The new St. Josephs hospital also opened on the cable line near Recreation Park.

The San Diego Union’s New Year’s 1891 summary of San Diego in 1890 included a section on the ‘cable road’, which had been in operation since July without any accident or repairs. The ‘first-class cable railway’ extended five miles through the center of the city to Mission Heights where a beautiful park of five acres and a spacious and handsome pavilion always attracted visitors and where every convenience is afforded to patrons of the road to spend a day enjoying the beautiful scenery. In June 1891 the cable railway company announced plans to celebrate its first anniversary with a musical entertainment and concert at the pavilion, and, in the evening, a grand ball. Late cars would be run to accommodate such as desire to attend and remain out until late in the evening.

However, behind the scenes, all was not well with the cable railway. It had been backed by the California National Bank, founded in January 1888 by D. D. Dare and J. W. Collins, who were also the principal founders and directors of the cable company. One day in November 1891 the California National Bank failed to open and despite a reassuring notice on its doors, its ‘temporary suspension’ proved to be permanent. It turned out that the bank had been little more than a front and that Collins and Dare had looted as much as $880,000 from its stockholders and depositors, a staggering sum in the 1890s, some of which had been used to fund their cable railway. Dare fled the country, reportedly for Italy, but Collins was arrested in San Diego in February 1892 and charged with embezzling $200,000 of the bank’s funds. Rather than be taken to jail, Collins, who had also suffered a personal tragedy when his entire family drowned in a yacht accident the year before, shot himself in his hotel room while the marshal waited for him outside.

In March 1892, unable to pay creditors, its financial backing cut off and its principal officers dead or in hiding, the company was ruled to be insolvent under the insolvent act of 1880. It was forbidden to transfer any property or to collect or receive any debts and the sheriff was appointed to take charge as receiver. The cars would continue to run, however, and Judge Puterbaugh authorized the sheriff to purchase coal to keep them running. The judge also granted a request for $10 to employ musicians to attract people to the pavilion on Sundays. This would be to the advantage of the creditors and the public would enjoy the very excellent programs. Other expenditures were approved to repair and maintain the road bed and keep it in good condition.

In September 1892 Judge Puterbaugh authorized the receiver to purchase new cables for the line and to raise funds to pay for them by issuing ‘receiver’s certificates’. Two new cables were ordered and one had arrived but on October 15 the receiver reported to the judge that there was no money to move the cable from the depot and put it in position and that no more receiver’s certificates could be sold. He asked the judge to sign an order to stop the operation of the railway and Judge Puterbaugh did so. Although there were occasional rumors that the slot wheels were being oiled and of a quiet bustling at the power house in anticipation of reopening the line, San Diego’s cable railway never ran again.

In September 1893 the Union reported that a controlling interest in the San Diego Cable railway company had been acquired by the Electric Storage railway company and that it had shipped three cars of the ‘electric storage pattern’ to run on the cable line. Nothing more was heard of this venture, however, and the cable company continued to be run by a court-appointed receiver. The big steel cable purchased for the cable line and stored at the Santa Fe depot was sold at auction for $1,355.

In September 1894 it was announced that preparations had been made to reopen the street railway leading to the fine pavilion at the end of the road overlooking Mission Valley, formerly a popular resort for dancing and Sunday concerts, and one of the most pleasant places of resort within reach of busy people. To bring it within reach again, a line of horse cars would operate over the rails of the cable railway from the end of the existing electric railway on upper Fifth Street. The cars would be the cable cars from the former cable railway and three horses would be attached to each car. R. H. Dalton, then the receiver of the cable railway, would be general manager of the new line. A first class lunch counter would be maintained at the pavilion.

In January 1895 Judge Puterbaugh authorized the receiver of the Cable Railway Company to sell the power house, machinery and other property and in February the assets of the cable company were sold at public auction to George B. Kerper of Cincinnati for $17,000. Kerper said he intended to resume operations as soon as possible, probably within four months. A month later, in March 1895, Kerper announced the sale of the cable line to a syndicate of eastern capitalists for $55,000, while retaining a three-fourths interest. The syndicate would expend another $25,000 to ‘electrize’ the line

The syndicate of eastern capitalists incorporated in April 1896 as the Citizens Traction Company, with a mission to take over the property, rights and franchise of the San Diego Cable Railway and transform it into an electric road. Kerper would be president and there would be no immediate change from the route of the cable railway, but new features would be introduced at the pavilion end of the line. The pavilion grounds, Mission Cliff Park, would be ‘conducted on temperance principles’ but a hotel would be erected on adjoining land where a public garden would be maintained and ‘something stronger than lemonade will be obtainable under rules of good order’. The Traction company expected to have the new line in operation by July 1 and to generate the electric power at the power house at Fourth and Spruce Streets. The company would convert the former cable cars to electric power and continue to run them over the narrow gauge rails of the former cable line.

The Citizens Traction Company did operate on the route of the former cable railway for another year or so but in early 1898 it was acquired by the San Diego Electric Railway, the former San Diego Street Car horse car system that had been purchased by the Spreckels interests in 1892 and converted to electricity. The San Diego Electric Railway already had a line on Fifth Avenue from downtown to University Avenue, so the portion of the Citizens Traction line from University to Mission Cliff Park was converted to standard gauge and a connection made to the Fifth Avenue line to extend it to the pavilion. The rest of the Citizens Traction line, the former San Diego Cable Railway, was abandoned. The power house was sold in 1902 and torn down in 1903; the Union reported that although the work had been kept quiet for fear of collecting a crowd the stack had been blown up on March 17. The tracks on Fourth, C and Sixth streets were also removed in 1903, the last visible signs of San Diego’s cable railway.