A massive pine tree growing along the west side of Ingraham Street south of Fortuna Drive in Pacific Beach recently blew over in a fierce windstorm, killing a passing motorist. The story in the San Diego Union-Tribune mourned the victim, a popular musician on her way to a performance, but also noted that many residents expressed a fondness for the tree, which one likened to an old friend; ‘I’ve known that tree for a long time. It was an icon, it really was’. Some residents estimated the tree was about 100 years old. Although this particular tree probably wasn’t that old, there are trees in Pacific Beach that are that old or older and many others which may be considered icons or old friends.

The most iconic tree in Pacific Beach would be the Kate Sessions Tipuana tree which stands on the site of her former nursery at the corner of Garnet Avenue and Pico Street. It has been a local icon for at least 75 years; an item in the San Diego Union’s Public Forum in June 1941 written by Max Matousek, a former foreman at her nursery, encouraged all tree-lovers to visit it the next week-end when it would be in flower, a mass of golden yellow and a living monument to Kate Sessions. He described the tree, probably about 15 years old at the time, as 35 feet tall and spreading its branches 65 feet in one direction and 55 feet in the other, one of the finest and largest specimens in Southern California.

Kate Sessions had come to San Diego in 1884 to replace the principal of the Russ School, predecessor of San Diego High School, who had abruptly resigned. However, she soon resigned herself, entered the nursery business and became active in civic organizations dedicated to improving and beautifying San Diego by planting trees (civic leader Julius Wangenheim later recalled that she apparently decided it was easier to get something out of the good earth than into the heads of young San Diegans). She was allowed to use a portion of the City Park, now Balboa Park, in exchange for planting and caring for 100 trees and donating an additional 300 trees in boxes to the city each year. She moved her nursery from the park to Mission Hills in 1905 and in 1912 acquired property in the foothills above Pacific Beach for her nursery operations. In 1924 she purchased property on both sides of Rose Creek north of what was then Grand and is now Garnet Avenue, and moved her sales office from Mission Hills to that location. Apparently she planted the Tipuana tree shortly after this move; in 1946 it was said to have been planted over 20 years before. She became a Pacific Beach resident in 1927 and died at the age of 83 in 1940.

In 1941 the Federal Public Housing Authority expropriated most of eastern Pacific Beach to build the Bayview Terrace housing project for defense workers and their families. An announcement of the project noted that the nursery formerly owned by the late Kate Sessions, prominent San Diego horticulturist, was included in the site, and the blooming acacia trees, long a landmark in San Diego, would be preserved in a proper setting. The preservation effort apparently extended to the Tipuana tree as well, which survived this project and others which threatened its future.

In July 1960, for example, the Union reported that a tree planted 40 years ago by a woman who brought greenness to San Diego was scheduled for alteration as the march of progress cut under its friendly boughs. The street under its friendly boughs, now Garnet but by then called Balboa Avenue, was being widened and traffic lanes would pass from 7 to 10 feet from the base of the tree, which might have made it necessary to trim branches to allow vertical clearance and remove some minor roots. However, city officials backed down after the Pacific Beach Garden Club and the Pacific Beach Women’s Club organized a campaign to protect the tree and modified the plan to add a 15-foot buffer between the street and the tree. ‘I know of no one in city government who wants to harm a twig on this fine old tree’, said the city park and recreation director. ‘We’re going to do nothing to damage it’. A senior design engineer in the city engineer’s office agreed, saying ‘our instructions are to avoid damaging the tree in any way’.

Emboldened by their success, the campaign to protect Kate Sessions’ Tipuana tree then petitioned the state park board to make the tree a state historical monument, and in May 1961 their proposal was accepted. A story in the Union reported that the tree, said to have been planted in 1905 (years before Kate Sessions first acquired property in PB and nearly 20 years before she owned the property where it stands), would become a state historical monument. A plaque recognizing Kate Olivia Sessions’ Nursery Site and commemorating the life and influence of a woman who envisioned San Diego beautiful was dedicated on July 7, 1961. The plaque was actually mounted on a stone monument under the tree and didn’t refer to the tree at all, but news reports emphasized that the Tipuana tree, said to be 50 years old, was the actual landmark.

The San Diego Union’s report on the campaign to save the Kate Sessions Tipuana tree also mentioned that construction crews were trying to preserve another, even larger tree believed planted by Miss Sessions on the construction site for the Capehart housing project (successor to the Bayview Terrace project and now the Admiral Hartman Community). This tree, thought to be a Ficus, was located on a promontory overlooking Mission Bay about 1 quarter mile south of Kate Sessions school. This description matches a huge Moreton Bay Fig tree (Ficus macrophylla) still growing today behind houses near the intersection of Chalcedony and Donaldson Drive, south of Kate Sessions school and overlooking Mission Bay. It is unlikely, however, that this tree was planted by Kate Sessions; it actually appears to be one of the last remaining signs of the area’s lemon ranching past.

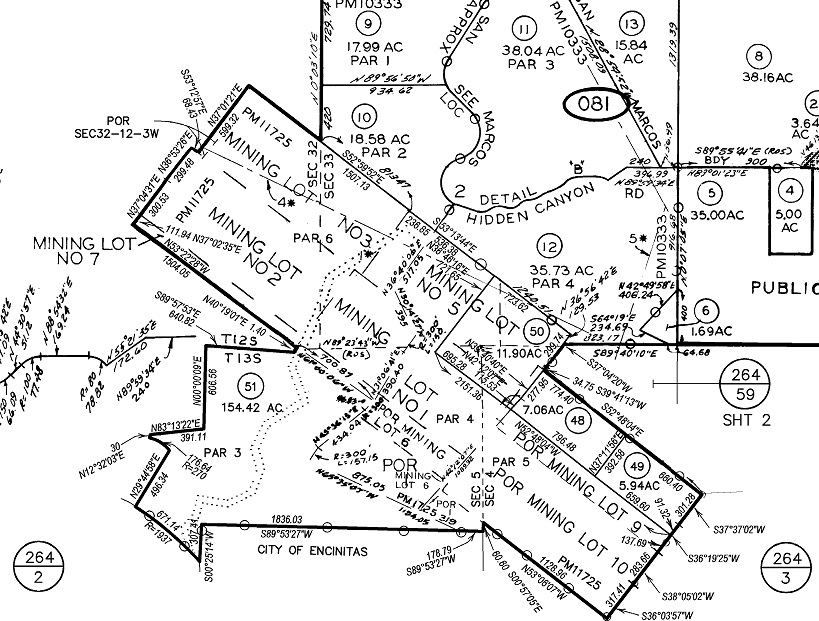

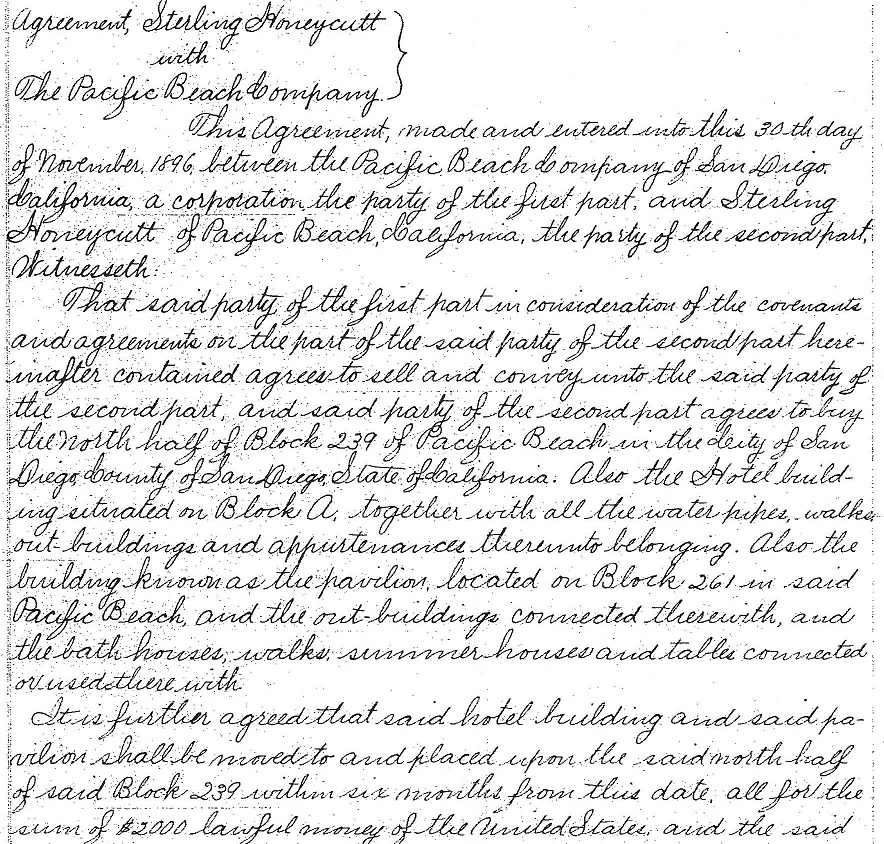

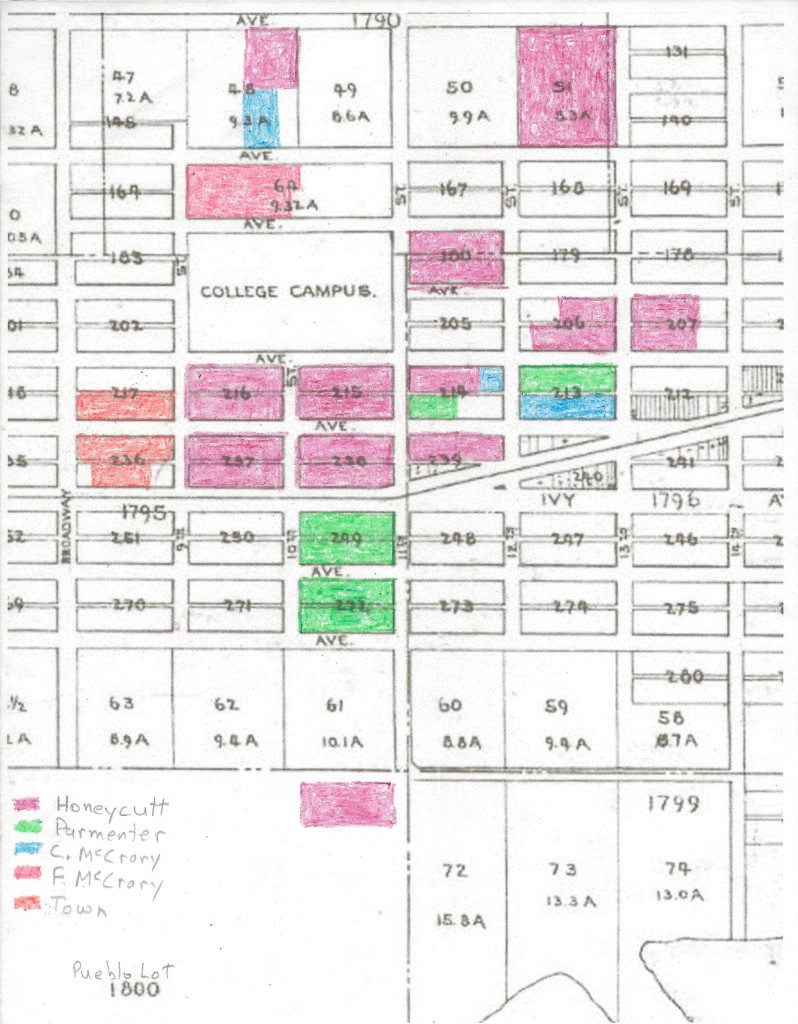

For over a decade beginning in 1892 life in Pacific Beach revolved around growing, packing and shipping lemons. Most of the lemons were grown on ‘acre lots’, parcels of approximately ten acres corresponding to pairs of today’s residential blocks. Most acre lots were located on what were then the fringes of the community, south of Reed Avenue and north of Diamond Street, and there are still traces of the former lemon ranches to be seen in these areas. The large two-story frame home at 1860 Law Street was originally the ranch house for the Wilson and Bowers lemon ranch on Acre Lot 34, now the two blocks surrounded by Lamont, Chalcedony, Kendall and Beryl streets (although the house, built in 1892, was moved from other side of Law about 1912). Two other ranch houses, at 1932 Diamond, built for the Coffeens in 1895, and at 4775 Lamont, built for the Roxburghs in 1904, remain on Acre Lot 50, the two blocks east of Lamont between Diamond and Chalcedony.

On other former acre lots the ranch houses have disappeared but the sites are still marked by the trees which once stood next to them. The two blocks east of Olney Street between Chalcedony and Beryl where the large Moreton Bay Fig tree stands was once Acre Lot 30, where Frank Marshall established a lemon ranch in 1894. A panoramic photo of Pacific Beach from the east taken in 1906 shows lemon groves and a ranch house surrounded by large trees on this site.

The lemon groves eventually died out and after the area was reconfigured for the Bayview Terrace housing project in 1941 the ranch house had also disappeared, but the tree was spared and can be seen in an aerial photo of the area from 1946. The builders of the Capehart housing project also succeeded in their efforts to preserve this iconic tree, saving the last visible reminder of the Marshall’s lemon ranch.

Trees are also the only survivors of other former lemon ranches in Pacific Beach. On the former Acre Lot 33, east of Lamont between Chalcedony and Beryl streets, a ranch house built for Wilson and Bowers in 1893 was torn down in the 1940s and the entire area was cleared for one of the first planned developments in Pacific Beach, Lamont Terrace (the homes with the brick chimneys and shingle siding). The only thing left standing was another Moreton Bay Fig tree which once stood beside the ranch house and is now in front of the house at 1922 Law.

On Acre Lot 49, west of Lamont between Diamond and Chalcedony, the house on Mary Rowe’s lemon ranch was demolished in the 1950s but a large palm tree which once marked her ranch house still stands in front of the apartment buildings at 1828-1840 1/2 Missouri.

In other parts of Pacific Beach, it is not individual trees but rows of trees, many of them over a century old, which have become iconic. In 1907 Folsom Bros. Co., which owned most of Pacific Beach and was trying to attract buyers by grading streets and laying sidewalks and water mains, also advertised that avenues of fine palms were being planted. These rows of palms still line parts of Lamont and Hornblend streets. The rows of palms along Bayard Street south of Grand Avenue and Pacific Beach Drive west of Bayard were also planted in the early years of the twentieth century. These trees lined the approach to Braemar Manor, the bayside mansion of the F. T. Scripps family and now the site of the Catamaran Hotel.

The group of Canary Island palms on the west side of Bayard between Reed and Thomas Avenues once stood in front of the Rockwood Apartments, later the Rockwood Home for the Aged, built in 1904 (2022 note; these palm trees have been cut down).

Another century-old Canary Island palm tree is growing in the patio of the Pacific Beach Presbyterian Church at Garnet Avenue and Jewell Street. The church’s web site actually presents its history through the character of this tree; ‘My name is Phoenix Canariensis . . . I live and grow in the patio of the Pacific Beach Presbyterian Church. I really don’t know where I came from but that’s not important because new life began for me in 1915 when the Ladies Aid Society transplanted me to beautify the barren sandy soil around their church’. After recounting a century of history, the tree describes its present environment; ‘I now live on the busiest street in all of San Diego. I am completely surrounded by businesses and apartments. Parking is a problem. People from the streets sometimes sleep in this patio, giving testimony to the gravity of the times’. It even considers its future; ‘Some say that the life of a Canary Date Palm is about 80 years. I know that I shall soon complete my cycle of life. The men seem to know it too. They are giving me extra attention . . . I even see a new family of palm trees in the refurbished patio’.

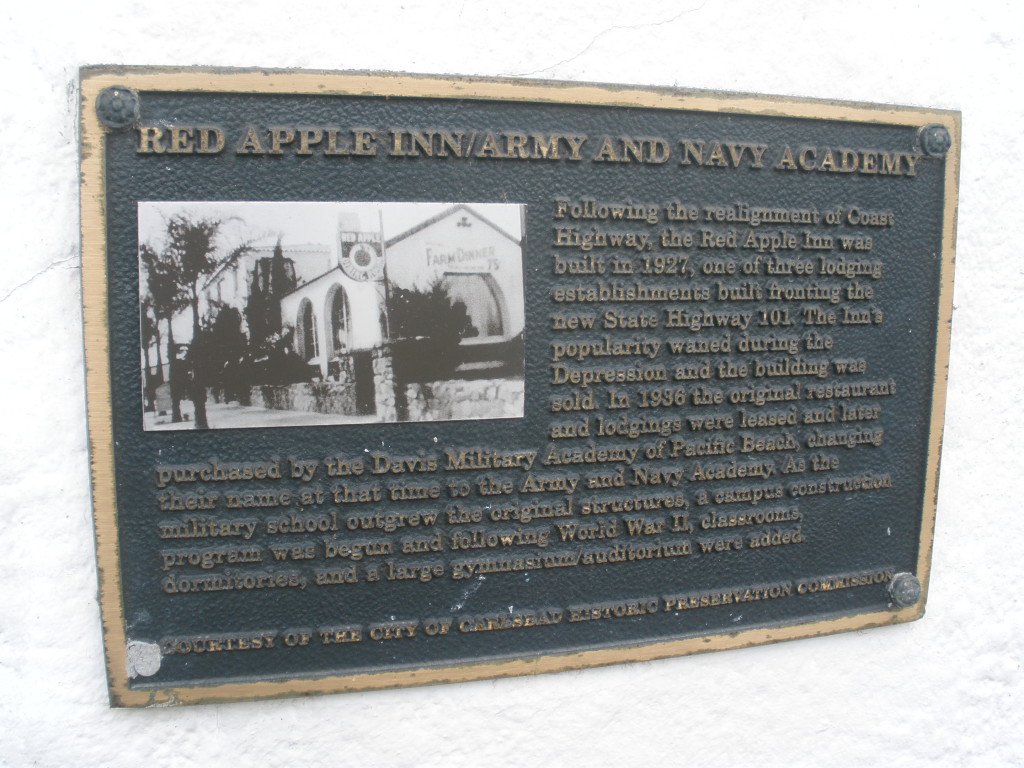

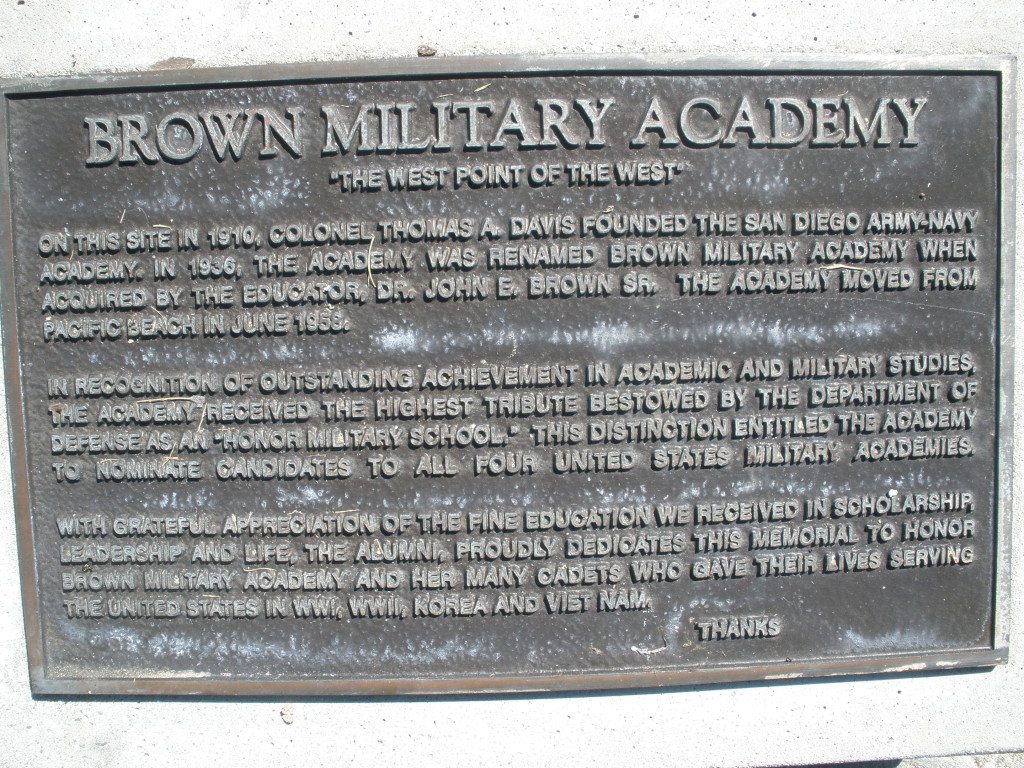

Other trees in Pacific Beach may not qualify as iconic but could still be considered old friends. When I was growing up on Diamond Street across from Brown Military Academy in the 1950s we had a decent view to the southwest, including the bay, Point Loma and the ocean. Before that view was obscured by the glaring Newberry’s sign in 1961 and completely blotted out by the Plaza Apartments in 1970, one of the most prominent landmarks visible from our front window was a tall Norfolk Island Pine tree, perfectly symmetrical, growing a few blocks south.

We traced it to Hornblend Street, just west of Kendall Street, where it is still growing in front of the historic house which is now the Baldwin Academy. It must be about 90 years old; it was already tall in an aerial photo of Brown Military Academy taken in 1938. I seem to recall that it had a lighted star on top during the holiday season, although I can’t imagine how anyone could have placed it there.

After last week’s fatal accident in Pacific Beach city crews went to Ocean Beach to cut down a pair of Torrey Pines that the city had deemed unstable and a threat to public safety. According to the Union-Tribune, a local resident stopped to see what was going on and became infuriated when he was told that two historic trees planted in the 1930s were going to have to come down. He placed himself in front of one of the trees, defending it from the city workers, presumably brandishing chainsaws, until they were able to convince him that the trees had been condemned. He then walked away, unable to watch the destruction. Other residents also joined in the complaints, saying that the trees were some of the most historic in that coastal community. The Torrey Pines were eventually cut down, but this incident again showed the fondness that a community can express for their historic trees.