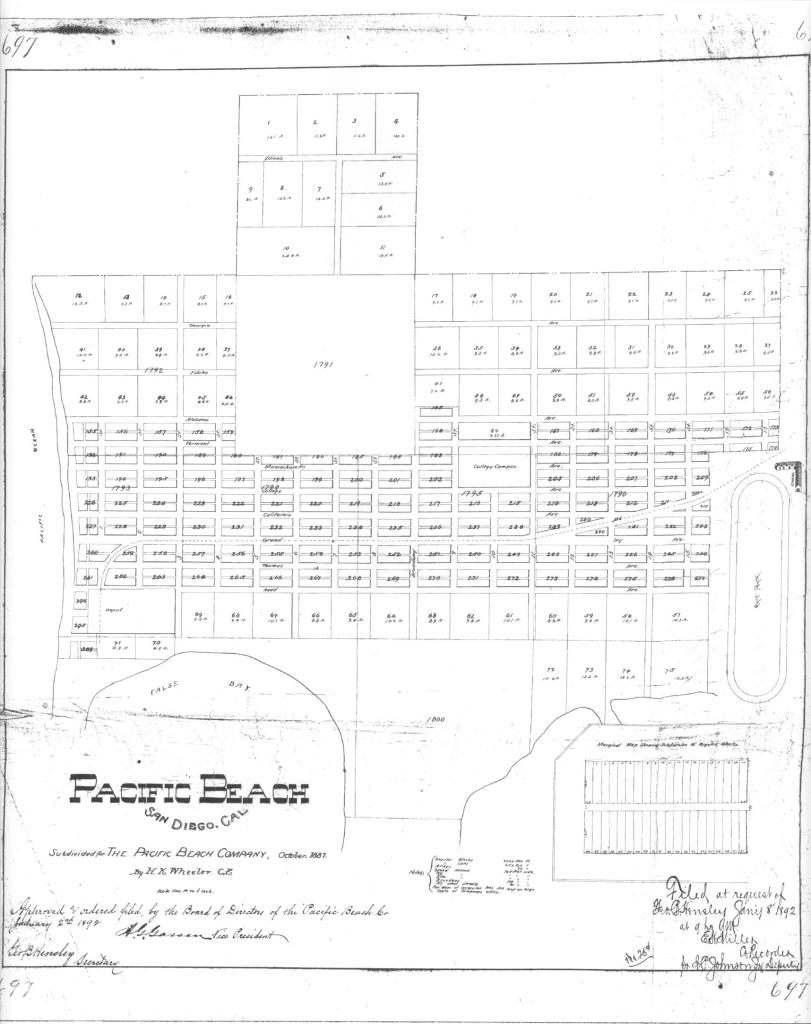

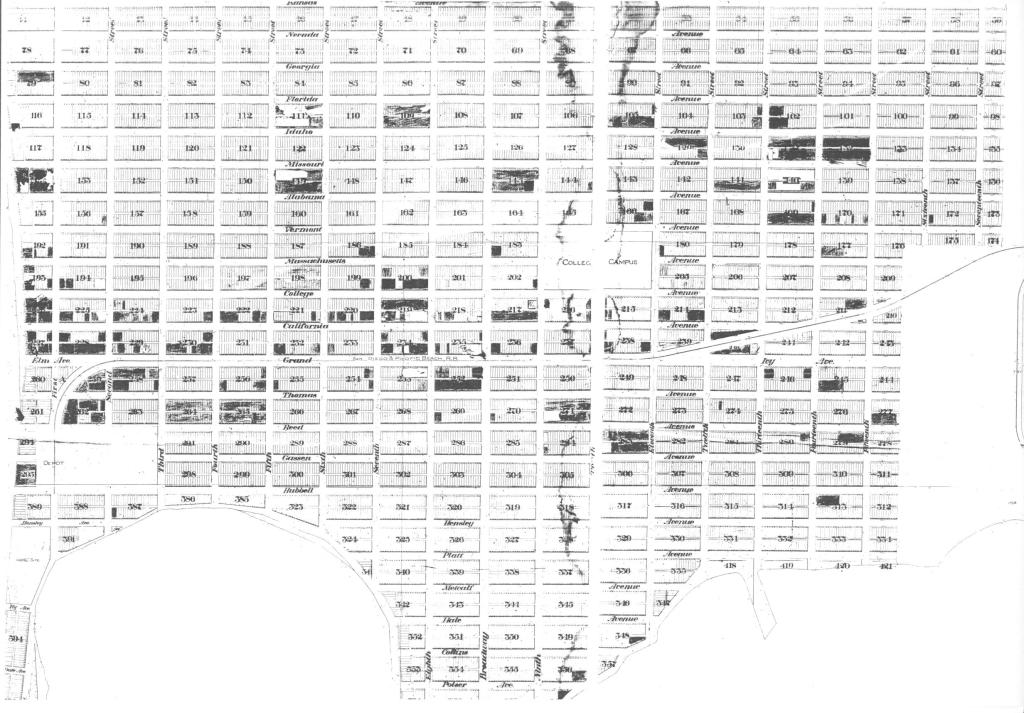

The Pacific Beach Company’s original subdivision map from October 1887 divided the area between the Pacific Ocean and Rose Creek and between Mission Bay and the Mount Soledad foothills into rectangular blocks separated by east-west avenues and north-south streets. Grand Avenue ran through the center of Pacific Beach and was also the right of way of the San Diego & Pacific Beach Railroad. South of Grand, the avenues were named after officials of the Pacific Beach Company; D. C. Reed, J. R. Thomas, etc. The avenue south of Reed, now Oliver, was named for A. G. Gassen and the avenue south of Gassen was named for O. S. Hubbell. Like most of the other avenues and streets on the original map, Hubbell Avenue was 80 feet wide and perfectly straight from one side of the community to the other. Most avenues and streets in Pacific Beach still are, but not the former Hubbell Avenue. It was wiped off the map of Pacific Beach along with everything south of it after only a few years, and although the subdivisions which grew up around its former route generally provided for a comparable roadway, the sections in different tracts did not necessarily line up, resulting in the odd alignment of the street that is now Pacific Beach Drive.

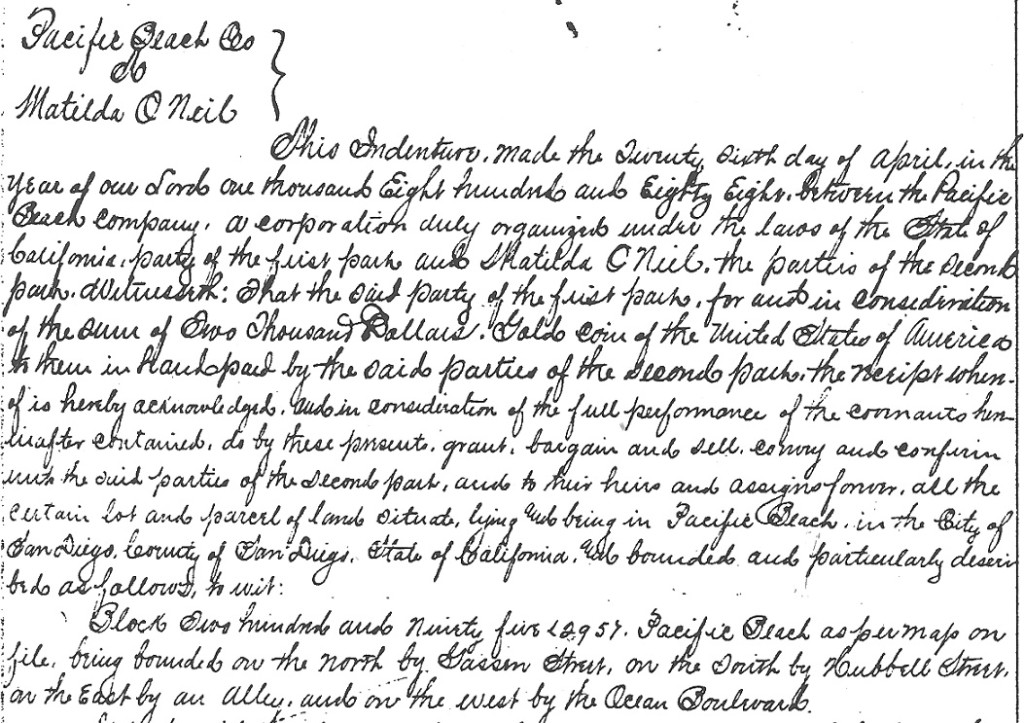

The Pacific Beach Company’s opening sale was held in December 1887 and one of the first purchases was Block 295 ‘being bounded on the north by Gassen Street, on the South by Hubbell Street, on the East by an Alley, and on the West by the Ocean Boulevard’ (by Matilda O’Neil for $2000 gold coin of the United States of America). However, most purchasers preferred more central locations closer to Grand Avenue and only one other deed was recorded for property along Hubbell Avenue (for lots 1-10 of Block 313, east of today’s Olney Street, then at the mouth of Rose Creek).

When San Diego’s ‘great boom’ collapsed in the Spring of 1888 thousands of would-be purchasers of residential lots left the area, and the community’s prospects were further diminished when the San Diego College of Letters closed in 1891. The Pacific Beach Company decided to market its tract as an agricultural district and in 1892 recorded a new subdivision map, Map 697. Map 697 retained the residential block structure and the streets and avenues in the central portion of Pacific Beach, generally the area between Reed Avenue and Alabama Avenue, now Diamond Street, but converted most of the area north of Alabama into acreage property, ‘acre lots’ of about 10 acres each. Many of the avenues and the streets that had extended into this acreage property were also gone from Map 697.

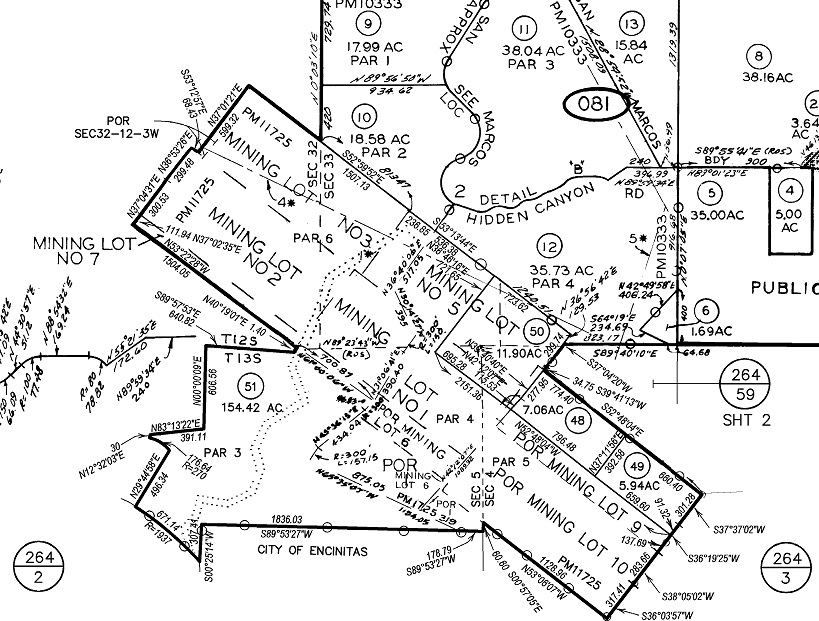

South of Reed Avenue the changes to the map were even more extensive. San Diego had inherited the lands of the Mexican Pueblo of San Diego and these pueblo lands had been platted into pueblo lots. Pueblo Lots 1800, 1801, 1802 and 1803 covered land in what are now Crown Point and Mission Beach. These pueblo lots had been included in the original 1887 map of the Pacific Beach subdivision but were not included in Map 697, except for a few parcels in Pueblo Lot 1803 northwest of Mission Bay. The northern boundary of Pueblo Lots 1800 and 1801 coincided with the north side of Hubbell Avenue, so the streets, avenues and lots south of Hubbell Avenue, including Hubbell Avenue itself, disappeared from the map of Pacific Beach. The area between Reed Avenue and the northern boundary of Pueblo Lots 1799, 1800 and 1801 was mostly reconfigured into acre lots of about 10 acres, also eliminating Gassen Avenue. Pueblo Lot 1799, east of Pueblo Lot 1800 and north of Mission Bay was retained in Map 697 and reconfigured into acre lots of about 13 acres. In the northern portion of Pueblo Lot 1803, Block 389 was retained and two new acre lots, 70 and 71, were created.

The acre lots created by Map 697 in 1892 proved popular and many were purchased and put to use as lemon ranches, contributing to a period of relative prosperity in Pacific Beach lasting more than 10 years. One of the first lemon ranches was established on Acre Lot 61, south of Reed and west of Lamont, purchased in 1892 by O. H. Raiter and extended in 1894 to the adjoining Acre Lot 62 on the west.

The Pacific Beach Company was dissolved in October 1898 and the remaining unsold property distributed to its shareholders, but in November 1898 the trustees purchased the northern 61 feet of Pueblo Lot 1800, effectively adding 61 feet to the southern edge of the community in this area. On the same day that this deed was recorded, another deed granted Eliza Turner a five-acre parcel south of the 61-foot strip, the northwest corner of the remainder of Pueblo Lot 1800. In 1902 A. J. Dula and O. M. Schmidt purchased the eastern half of Pueblo Lot 1800, less the 61-foot strip on the northern boundary and the five-acre parcel at the northwest corner of the remainder, and subdivided it as Fortuna Park Addition. In 1903 they purchased the western half of the pueblo lot, less the 61-foot strip on the north and about six acres in the southwest corner, and subdivided it as Second Fortuna Park Addition. The subdivision maps for Fortuna Park and Second Fortuna Park both included an 80-foot-wide street along their northern boundaries named Pacific Avenue.

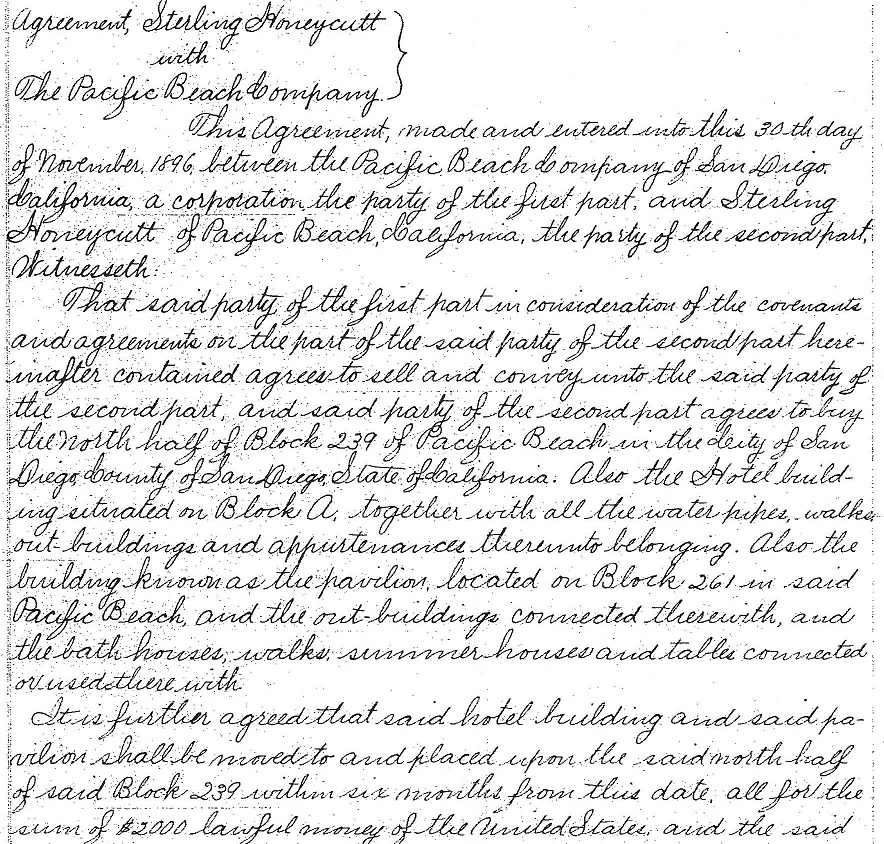

East of Fortuna Park, and within the adjoining Pueblo Lot 1799, Venice Park was subdivided in 1906 from Acre Lots 72 and 73. North of Venice Park, in Pueblo Lot 1796, Map 922 had subdivided Acre Lots 57, 58, 59 and 60 in 1904. The Venice Park and Map 922 subdivisions were divided by a street that was also called Pacific Avenue, but this section of Pacific Avenue was separated from the Fortuna Park section by the 660-foot width of the five-acre tract. These two sections of Pacific Avenue also were not aligned with each other; the eastern portion extended 12 feet north (Map 922) and 60 feet south (Venice Park) of the pueblo lot line and the portion in the Fortuna Park additions to the west extended from 61 to 141 feet south of the pueblo lot line. In 1909 the five-acre parcel was purchased by Sterling Honeycutt and subdivided as Sterling Park, but although the map of Sterling Park referenced the sections of Pacific Avenue to the west and the east it did not set aside space for a connection between them.

In 1899 Fred T. Scripps had purchased property in the northern portion of Pueblo Lot 1803, including Acre Lot 71, for his bayside mansion Braemar Manor. In 1903 he acquired adjoining property, including Acre Lots 69 and 70, which extended his holdings north to Reed Avenue and east to Dawes Street, and in 1907 filed a map for the Braemar subdivision. The map of Braemar included a street named Pacific Avenue, 60 feet wide, along the northern boundary of Pueblo Lot 1803. The 1925 Southern Title Guaranty Company’s Subdivision of the adjoining Pueblo Lot 1801 also included a 60-foot-wide street named Pacific Avenue along its northern boundary, which connected with the Pacific Avenue in Braemar and effectively extended the street a half-mile to the east. However, at Frontera Street (now Riviera Drive) the eastern side of the Southern Title Co. subdivision met the western side of Second Fortuna Park, where Pacific Avenue ran 61 feet south of the pueblo lot line. The 61-foot difference in the alignment of these two sections of the former Pacific Avenue explains the bend in Pacific Beach Drive at Riviera Drive today.

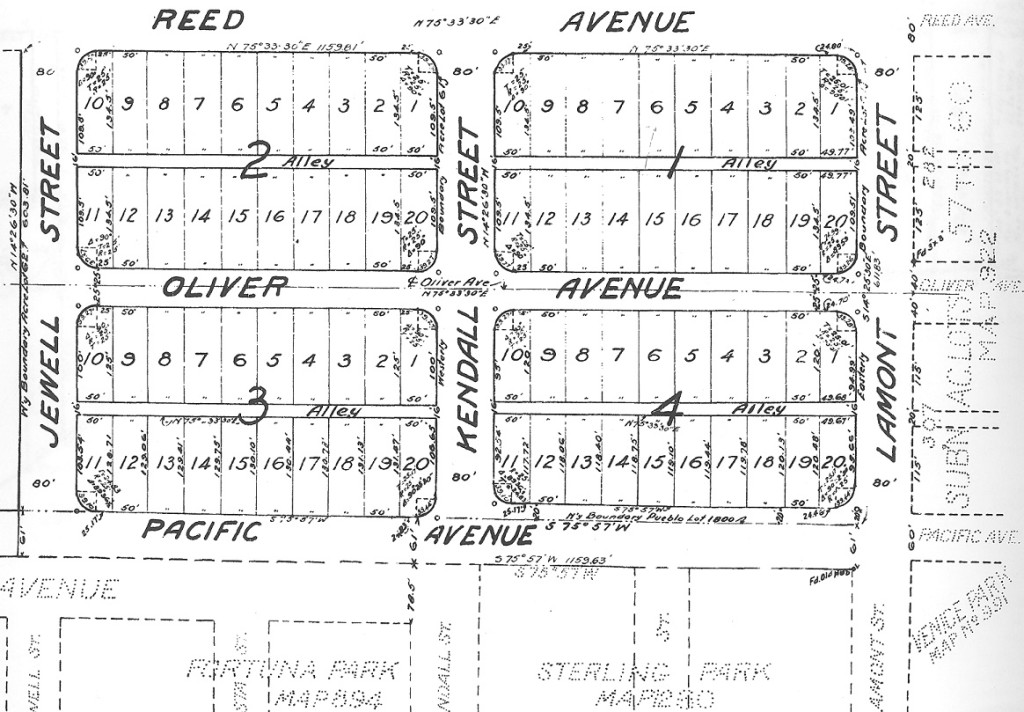

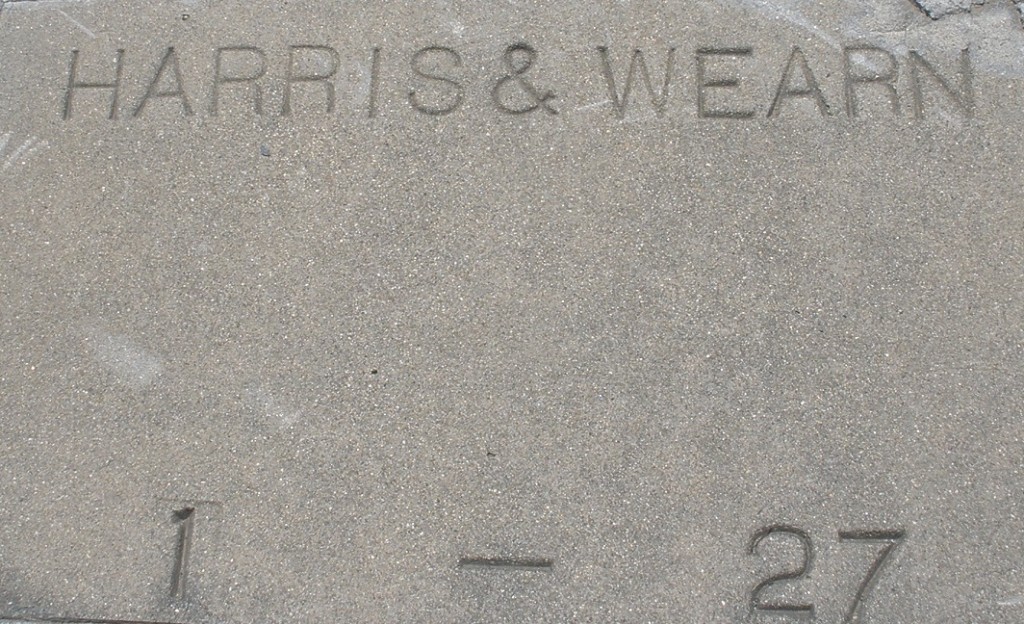

Acre Lots 61 and 62, where the Raiters had started one of the first lemon ranches in 1892, was located north of Fortuna Park and Sterling Park and separated from them by the same 61-foot strip of Pueblo Lot 1800. In 1926 these two acre lots and the 61-foot strip south of them were subdivided as Pacific Pines. The map of Pacific Pines created four blocks surrounded by Jewell and Lamont streets, Reed Avenue, and a new section of Pacific Avenue, connecting the sections west and east of Sterling Park. The Pacific Pines section of Pacific Avenue included all of the 61-foot strip south of the pueblo lot line and also, between Lamont and Kendall streets, an additional 20 feet of the former Acre Lot 61, north of the pueblo lot line. In the block between Kendall and Jewell streets, the sections of Pacific Avenue in Fortuna Park and Pacific Pines were contiguous, creating a street over 140 feet wide. The developers announced that it would be divided into two roadways with a park in the center, a configuration that exists to this day. The streets of Pacific Pines, including Pacific Avenue, were among the first in Pacific Beach to be paved, in 1927.

When travel by automobile became possible in the first years of the twentieth century the main route between San Diego and Los Angeles and the north passed through Pacific Beach, along Garnet Avenue and Cass Street. In 1915 a bridge over the inlet to Mission Bay opened an alternate route between San Diego and Pacific Beach through Mission Beach, connecting Mission Boulevard to Cass Street via Pacific Avenue and making these two blocks of Pacific Avenue an important link in the coast highway. The route through Mission Beach, including the sections on Pacific Avenue and Cass Street, was paved in 1924.

Highway traffic continued to increase, however, and in 1930 the city opened a new route through Rose Canyon. By 1935 this new ‘gateway to the north’ had been widened, straightened and paved from downtown to the city limits at Del Mar and the city decided that it should be called Pacific Highway. To avoid confusion with the existing Pacific Avenue in Pacific Beach the city council passed an ordinance in April 1935 that changed ‘all those portions of Pacific Avenue’ (and some previously unnamed segments) to Braemar Avenue. In June 1935 the new route to the north became Pacific Highway and Braemar Avenue, formerly Pacific Avenue and originally Hubbell Avenue, was renamed Pacific Beach Drive.