In January 1902 the San Diego Union reported that a new real estate firm, Folsom Bros., whose ad appeared in another column, had located at 1015 Fourth Street; ‘These gentlemen are from the east, having business affiliations there, and are enthusiasts on San Diego’s climate and natural resources’. The ad in the other column announced that Folsom Brothers, 1015 Fourth St., had some parties coming to San Diego from the east early in the year who contemplated investing and making their homes here, and invited owners who had houses or good building lots for sale to call their office; ‘Your chance for a sale will be better with us, as we have been hustling on the quiet outside of San Diego for the past year and do not depend merely on local transfers’. The new company also acquired a two-seat steam Locomobile, enabling them to hustle around inside San Diego as well.

The Folsom brothers, Murtrie (M. W.) and Wilbur (W. A.), were in their mid-20s in 1902 and their enthusiasm for the local climate and natural resources might have been encouraged by their parents, Mark and Helen Folsom, who had relocated to San Diego a few years earlier. Shortly after their debut in the papers, in March 1902, they reported that one of the parties they had recently induced to come here from the east, A. J. Dula of North Carolina, had purchased a 5-acre orange and lemon ranch in Chula Vista for $5000, and that they had other sales on the way.

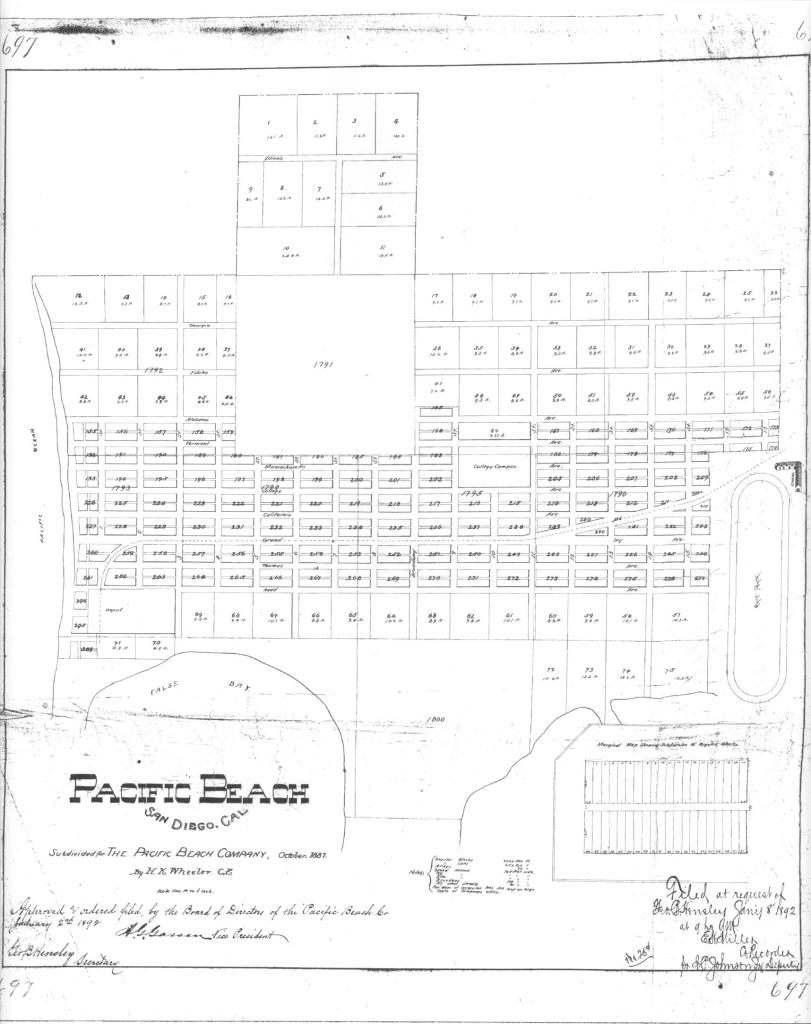

Aurelius J. Dula was a native of North Carolina, a Confederate veteran who had been wounded at Gettysburg and Cold Harbor and had been elected in 1895 to the North Carolina state senate. Although he was nearly 60 years old, he was also the Folsom brothers’ brother-in-law, having married their older sister Lillian in 1892. Although Dula and the Folsom brothers first collaborated on the lemon ranch in Chula Vista, they soon turned their attention to the Pacific Beach area and Pueblo Lot 1800, part of the endowment that the American city of San Diego had inherited from the Mexican pueblo and had granted to the San Diego Land and Town Company, a subsidiary of the Santa Fe Railroad, as a subsidy for building the railroad that connected San Diego to the east. Pueblo Lot 1800 is located within the perimeter of today’s Lamont Street and Crown Point, Moorland, Riviera and Pacific Beach Drives (pueblo lots were typically a half-mile square and 160 acres, but the southeast corner of this lot was cut off by Mission Bay).

In November 1902 A. J. Dula and O. M. Schmidt, a retired wholesale grocery merchant from St. Louis, purchased most of the east half of Pueblo Lot 1800, everything except the northerly 61 feet and 5 acres in the northeast corner, and filed a map subdividing it as Fortuna Park Addition. In February 1903 they bought most of the west half as well, everything except the northerly 61 feet and about 6 acres in the southwest corner, and filed a subdivision map for Second Fortuna Park Addition. Folsom Bros. Co., representing their brother-in-law and his business partner, placed ads in the local papers offering lots in these new subdivision for $25. A few months later, in August 1903, Dula granted all his right, title and interest in these two tracts (excepting any portions already sold) to M. W. Folsom, who in November 1903 granted this interest to his father, Mark Folsom (O. M. Schmidt followed suit in 1905, granting all of his remaining interest in Fortuna Park, Second Fortuna Park and all bay frontage or any other property in Pueblo Lot 1800 to Folsom Bros. Co.).

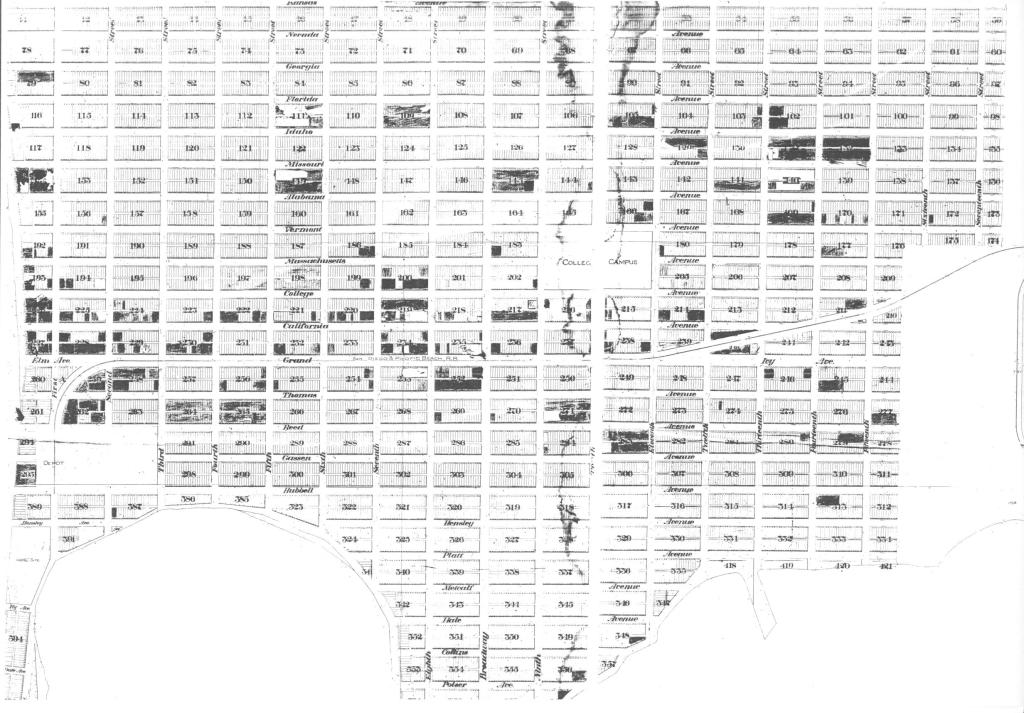

With a foothold in the Fortuna Park additions, Folsom Bros. Co. set its sights on the Pacific Beach subdivision on the other side of Pacific Avenue, as Pacific Beach Drive was then called. In 1903 Pacific Beach was primarily an agricultural community with an economy centered around lemon cultivation. The first lemon groves had been planted in 1892 and over the next few years had grown to cover over 300 acres. Nearly half of the 54 households in Pacific Beach enumerated in the 1900 census were lemon ranchers or involved in harvesting and packing lemons, and many of the rest were also engaged in agriculture, as ranchers, farmers, or farm laborers. The Folsom brothers believed that Pacific Beach had more potential as a residential district, and that this would be achieved by development; grading streets, lining them with curbs and sidewalks, and most importantly, building houses.

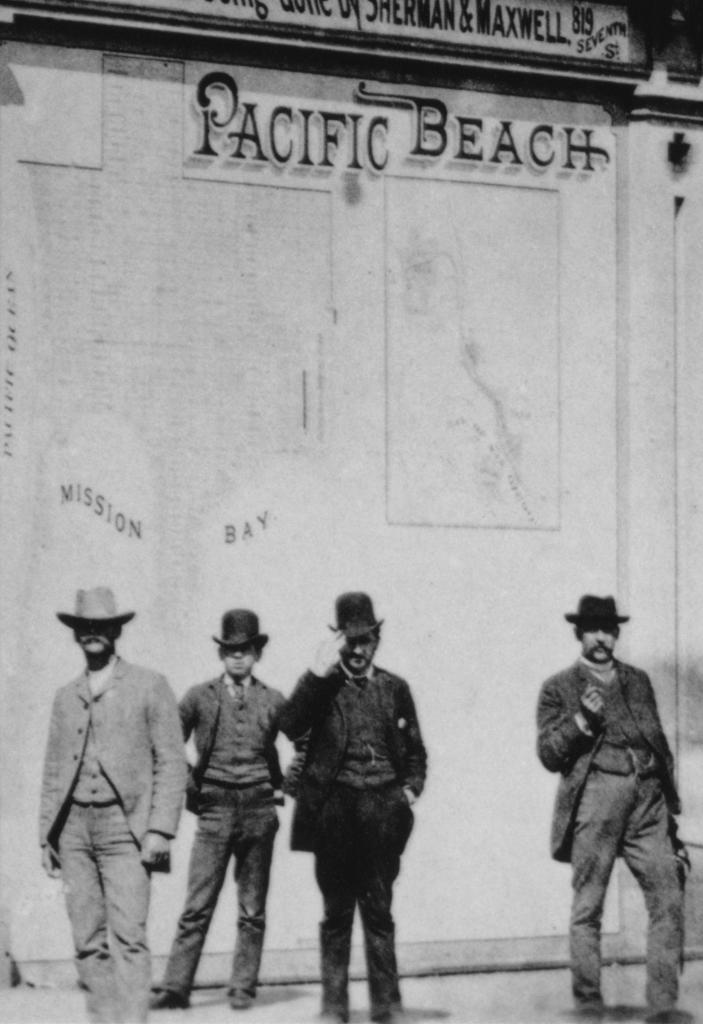

When the Pacific Beach Company had been dissolved in 1898 its unsold land in the Pacific Beach subdivision was distributed to the remaining stockholders, principally Oliver J. Stough, whose share amounted to about a hundred blocks, four thousand lots, nearly 660 acres or about 70% of the unimproved land in the subdivision. In November 1903 the San Diego Union reported that Pacific Beach had ‘changed owners’; the larger portion of the suburb had passed from Mr. Stough to the firm of Folsom Bros. Co. (although they noted that even with the deal closed and the papers in escrow the actual transfer was not expected to take place until later). When asked about their plans, M. W. Folsom replied that ‘improvement and development’ would best express what the future had in store for Pacific Beach. There would be houses, and lots of them, not mere renting or beachfront shacks, but homes, quiet, refined and beautiful homes. He declared that at least sixty first-class modern dwellings would be built within one year, probably constructed from cement blocks. He added that the original liquor-selling restrictions of the old Pacific Beach Company would be rigidly adhered to (all deeds granted by the Pacific Beach Company had included a clause banning the vending of intoxicating liquors, either directly or under some evasive guise). Folsom family members were among the participants in the planned housing boom; one of the first new homes, started in January 1904 at Thomas Avenue and Ingraham Street (then called Broadway), was to be the home of Mark Folsom. Plans were for it to be constructed of concrete, elaborately finished on the exterior, and surrounded by spacious lawns. The Dulas and Wilbur Folsom also built homes nearby on Broadway, while Murtrie Folsom’s home was on Garnet Avenue.

Folsom Bros. Co. also acquired other properties in Pacific Beach, including the hotel building which in 1897 had been relocated from its original location at the beach to the corner of Lamont and Hornblend streets, and in January 1904 it reopened as the Pacific Beach Hotel. In April they leased the 16-acre College Campus between Garnet Avenue and Jewell, Emerald and Lamont streets, together with buildings and improvements, and announced plans to convert the former San Diego College of Letters into a first class resort (the lease included an option to buy after one year, which Folsom Bros. Co. exercised in 1905). While the conversion was underway, Folsom Bros. Co. offered a $100 prize for the best name for their new hotel and in July 1904, after careful consideration of over 1200 entries, announced that the name finally selected was Hotel Balboa (the lucky winner, the first to suggest Balboa, had the choice of a $100 lot in PB or $100 in gold; nine other contestants, who had also mentioned Balboa, were given a consolation prize of $20 off any PB lot).

Over the next few years Pacific Beach did undergo a period of growth which many attributed to the Folsom Bros. Co.’s activities. The Evening Tribune reported in April 1904 that the sale of building lots by Folsom Bros during the past week had been unprecedented and that the recent growth in the population of PB was due to the enterprise of Folsom Bros. Co.; ‘on a number of occasions no less than five teams might be seen conveying prospective buyers through the suburb’. In August 1904 the Union noted the marked success of Folsom Bros. Co. in developing the suburb; ‘the large number of new residences and the amount of improvements fully attest to the rapid advance of this section of the city’. Twenty-one families were said to have been added to the population in the previous month. In response to their own growth, the Folsom Bros. Company filed articles of incorporation in August 1904, adding O. W. Cotton, F. M. Elliot and B. S. Kirby as stockholders and directors.

In July 1906 Folsom Bros. Co. secretary O. W. Cotton wrote a glowing testimonial about his company for the San Diego Union in which he said that in their three and one-half years of business they had grown from employing three people until today their regular payroll included from fifty to sixty names, and that this was just the beginning of what they planned to accomplish. An Alabastine stone plant, a factory for the manufacture of artificial stone or concrete building blocks, which had started as a little experimental block yard at Pacific Beach employing four men now employed thirty with a factory downtown. They had remodeled and rebuilt the Pacific Beach college, named it Hotel Balboa, and now have one of the most delightful year-round hotels on the coast.

Dr. Martha Dunn Corey was the first physician in Pacific Beach and, with her husband, had been among the first to attempt lemon ranching. She had moved away in 1900 to practice medicine in Ohio and when she returned in 1906 to set up a practice in La Jolla she claimed to be delighted with the changes she saw. She found the growth and improvement remarkable and said that every old resident of Pacific Beach should thank Folsom Bros. Co. for what they had done. Not everyone was ready to thank Folsom Bros. Co. for the growth and improvement, however. In January 1907 Pacific Beach rancher Wilbur Conover sent a letter to the common council complaining that ‘real estate town lot boomers’ were destroying numbers of fine trees and making a barren waste of what was once a beautiful section while grading ‘useless and silly 80-foot streets’ that there was no need for and no one wanted. O. W. Cotton explained to the council that the trees were within the areas dedicated for streets and were above the grade of the streets and had to go.

The 1903 transactions making Folsom Bros. Co. ‘owners’ of Pacific Beach had not actually been finalized at the time and for several years M. W. and W. A. Folsom, or Folsom Bros. Co., were listed as ‘trustees’ of these properties in the city lot books. In December 1906 another blockbuster land deal was announced involving the same parties and the same properties, which Folsom Bros. Co. had ‘held under contract for some time’ according to the papers, and this time deeds were recorded and Folsom Bros. Co. did become the owners of most of Pacific Beach. At the same time it transferred some of the properties which it already owned in its own right, including the College Campus, to Union Title and Trust Co. The completion of these transactions was accompanied by a reorganization of Folsom Bros. Co., with a number of prominent citizens including A. H. Frost and O. M. Schmidt, and Pacific Beach residents Sterling Honeycutt and H. L. Littlefield, added as stockholders. Frost and Schmidt joined the Folsom brothers and Cotton on the board of directors.

With its ownership in the tract established and reinforced with additional stockholders and capital, Folsom Bros. Co. renewed its efforts to market lots in Pacific Beach. A series of ads appeared in the San Diego Union predicting rapid increases in property values and encouraging buyers to ‘buy as early as you can at Pacific Beach’. An opening sale of 250 building lots was announced for January 1, 1907. Pacific Building Company, recently incorporated by prominent business men of San Diego and stockholders of Folsom Bros. Co., would be open for business January 1, and would build houses costing from $1,500 to $10,000 at Pacific Beach for any lot owner. The Pacific Building Company did open for business and did build homes in the Pacific Beach area; the report of building permits in the San Diego Union in early 1907 generally included at least one for the company in Pacific Beach or Fortuna Park, mostly of the ‘up-to-date bungalow type’. One of these up-to-date bungalows, built for Joseph Israel in 1907, is still standing at the southwest corner of Reed Avenue and Morrell Street (Joseph Israel was the son of lighthouse keeper Robert Israel and had grown up in the old Point Loma lighthouse).

In January 1907 work had begun on a ‘cut-off’ to allow the railway from San Diego to reach the Pacific Beach station at Grand Avenue and Lamont Street over the route of today’s Grand Avenue rather than the circuitous route it had taken around the former race track via Mission Bay Drive and Garnet and Balboa Avenues. The improvements to the line led to speculation that it would also be electrified, and possibly even continued beyond La Jolla to Los Angeles. Folsom Bros. Co. was quick to exploit the publicity surrounding the work; an ad in the Union announced that ‘dirt is flying’ on the new short-line to Pacific Beach, shortening the line and reducing travel time. It was the beginning of the re-construction of the whole line for rapid transit. The time to buy lots at Pacific Beach was NOW, not after the line was completed, since prices would be doubled and over on the day the first electric car passed.

Improvements to the infrastructure in Pacific Beach also continued in 1907. One project involved grading, curbs and sidewalks on Lamont Street from the railroad station at Grand Avenue north past the Folsom Bros. Co. offices in the former Pacific Beach Hotel and the Hotel Balboa to Emerald Street. Another project was improvement of the grounds of the Hotel Balboa itself and the grading of Kendall Street from the hotel to the bay, making a ‘splendid entrance into Fortuna Park’. A two-inch water main was also laid and ‘avenues of fine palms’ were planted.

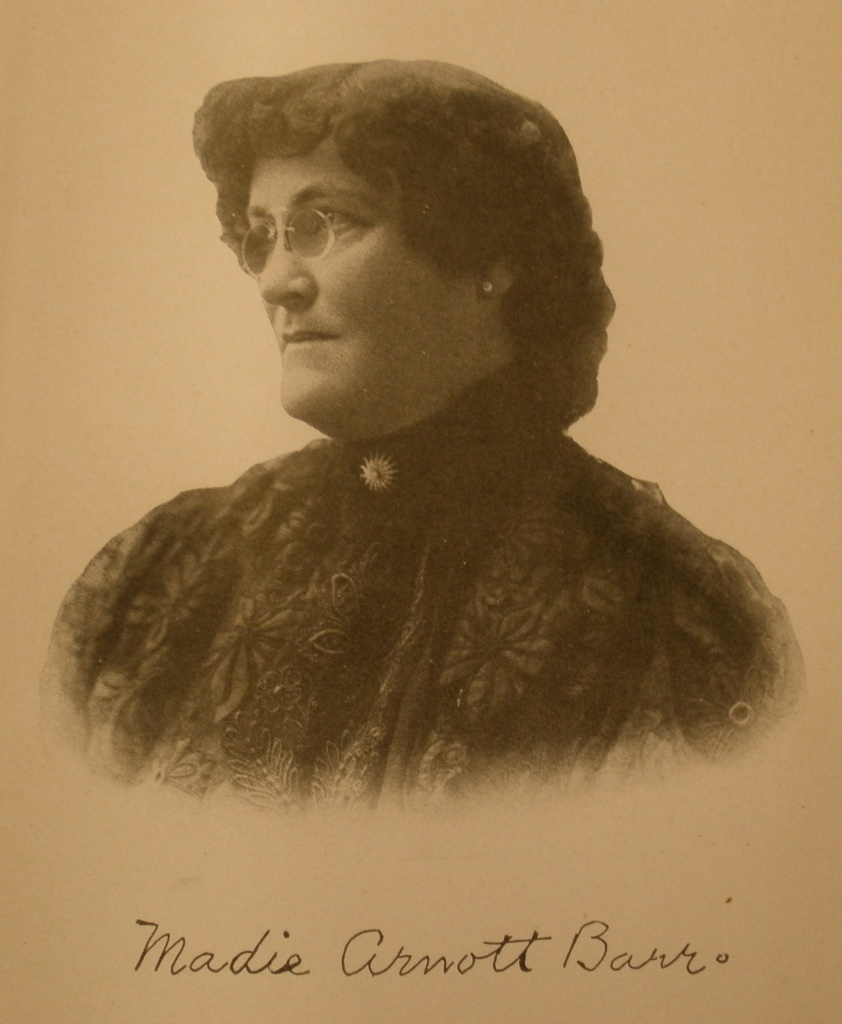

In March 1908 Folsom Bros. Co. further increased its stake in Pacific Beach property, purchasing 366 lots from Madie Arnott Barr for $40,000. This property was in the eastern half of Pueblo Lot 1791 west of Ingraham Street between Felspar and Chalcedony. The company also purchased what the San Diego Union called the ‘front door’ to Pacific Beach; the property on the south side of Grand Avenue, between the Brae Mar railroad station at Bayard Street and the ocean, giving it a large ocean frontage at the foot of Grand, which the paper predicted would soon be ‘graded and oiled’.

Further changes also occurred in the corporate structure of Folsom Bros. Co. in 1908. In February of that year, W. W. Whitson bought out the shares of O. W. Cotton, its secretary, and O. M. Schmidt, its treasurer, and several other stockholders, and was elected vice-president and treasurer. Murtrie Folsom continued as president and Wilbur Folsom became second vice-president and secretary. Cotton left the company to become president and general manager of Pacific Building Company. Later in the same year, November 1908, the Folsom brothers bought out Whitson and several smaller stockholders. Two new directors, Philip Morse and Dr. F. R. Burnham, were added to the board of the company, which then owned 4000-5000 lots and improved property in Pacific Beach, including the Hotel Balboa, and was valued at $1 million.

However, growth in Pacific Beach had slowed after 1907 as potential residents were increasingly moving to the new districts opened up by the extension of street car lines north and east of downtown San Diego. The lists of building permits published in the Union in 1908 often showed that Pacific Building Company had taken out six or eight permits, but generally none were for Pacific Beach and instead were for areas such as Mission Hills, Hillcrest, North Park and Mountain View. One list in 1909 showed Pacific Building Company with ten permits, including three in Point Loma and Ocean Beach (which were served by an electric railway) but none in Pacific Beach (the electric cars of the rapid transit line that Folsom Bros. Co. had predicted never did pass through Pacific Beach and the railroad was scrapped in 1917, although a portion of the right-of-way along the beach was incorporated into the San Diego Electric Railway line to La Jolla via Mission Beach in 1924).

In 1907 the San Diego city directory listed 170 names in 125 households for Pacific Beach, more than double the number reported in 1903. One indication of Folsom Bros. Co.’s involvement in that growth was that 20 of these residents were directly employed by Folsom Bros. Co., including laborers, gardeners, salesmen, a cook and a waiter, presumably at the Hotel Balboa, and the Folsom brothers themselves. In 1909 the city directory listed 193 residents in Pacific Beach in 130 households, barely more than were listed in 1907. The rise in property values predicted by Folsom Bros. Co. ads had also failed to materialize. In 1907 they had reported the sale of 125 lots at an average of $250. In 1909 pairs of lots in a bay-front block with unlimited views were selling for $295. The Hotel Balboa, which Folsom Bros. Co. had created from the former San Diego College of Letters in 1905 and turned into a ‘first class resort’ also did not live up to expectations. In 1909 a portion of the hotel was leased to the Pacific Beach Country Club and in 1910 the entire campus became the San Diego Army and Navy Academy.

In January 1910 the Folsom brothers announced that they had retired from active management of Folsom Bros. Co., and were joining forces with D. C. Collier, one of San Diego’s leading real estate firms, to form the Collier-Folsom Sales Offices (although they continued to hold a large stock interest in the company they had founded). A. H. Frost became president of Folsom Bros. Co. and in January 1911 changed its name to San Diego Beach Company. San Diego Beach Company, initially based in the same offices at the former Pacific Beach Hotel building, continued to own much of Pacific Beach and was a major player in the PB real estate market for decades. Ironically, one of its first major real estate transactions was the August 1910 sale of its interests in Fortuna Park, the Folsoms’ first foothold in the Pacific Beach area, to the Asher-Mollison Company.

The Folsom brothers’ association with D. C. Collier was brief, and by 1911 they were again in business together as the Folsom Investment Company, Pacific Beach property a specialty, with Murtrie as president and manager and Wilbur as vice-president and treasurer. They also still lived in Pacific Beach; Wilbur’s family, his mother Helen and the Dulas were neighbors on Broadway (Ingraham Street), and Murtrie’s family lived on Garnet Avenue. By 1912, however, they had all moved away from Pacific Beach (also to the new streetcar suburbs) and for the next ten or twelve years the brothers worked independently as salesmen and real estate agents.

After a long period of stagnation, the real estate market in Pacific Beach began to show signs of life again in the early 1920s. In 1924 Earl Taylor established a Pacific Beach business district centered at the corner of Garnet Avenue and Cass Street and anchored by the Dunaway Pharmacy building, built in 1925. In 1924, the San Diego Electric Railway opened the ‘Beach Line’ between downtown San Diego and La Jolla via Mission Beach which ran along what is now Mission Boulevard in Pacific Beach and was expected to boost the local economy in general and real estate values in particular. Once again, grading, paving and sidewalking of a new business center, this time on Garnet Avenue between Cass and the beach, was underway.

The Folsom brothers joined the anticipated real estate boom and attempted to re-enter the market they had dominated two decades earlier. For about a month, in June 1924, they advertised as Folsom Bros., general sales and development agents for Consolidated Pacific Beach Properties with their office, ‘Headquarters for Pacific Beach real estate’, at Garnet and Cass. However, while they maintained an office in PB for several more years by June 1926 their occasional ads in the Union, ‘Shank for bargains. He knows values at Pacific Beach’, referred readers to Joseph Shank, mgr. city office, Folsom Bros, 1126 7th St. In October 1926 Geo. Hawley announced that his company had opened an office at 1148 7th and that Folsom Bros. would also make it their city headquarters. In the end, the revival of the real estate market in Pacific Beach was brief, the great depression of the 1930s led to another downturn, and Folsom Bros. disappeared from the real estate scene.

In the 1930s Murtrie Folsom was described in city directories as a publisher or writer and on the 1940 census described himself as a statistician. In the 1940s, styling himself an ‘economic engineer’, he developed the idea for a ‘low-grade’ highway, a highway with grades of less than 3% and a maximum elevation of 4000 feet, between San Diego and Imperial County. He formed the Southwest Express Highway Association to promote his views and even travelled to Washington in the early years of the war to try to interest the military. Wilbur Folsom continued to sell real estate with occasional ads for individual properties in the local papers.

Although Folsom Bros. Co. actually owned the majority of Pacific Beach in the first decade of the twentieth century, and spent years improving and developing it, what little evidence there is of those activities is easily overlooked today. Gangs of men and teams of horses working for the company graded the streets and put in the cement curbs and sidewalks in some of the older sections of the community, especially in the area around Lamont and Kendall streets and Grand and Garnet avenues. The streets have since been paved but otherwise remain the same, and many sections of the curbs and sidewalks appear to date from those days. The most visible legacy of Folsom Bros. Co. though are the ‘avenues of fine palms’ which still line parts of Lamont Street and, after more than a century of growth, tower over the community that has also grown just like the Folsom brothers said it would.