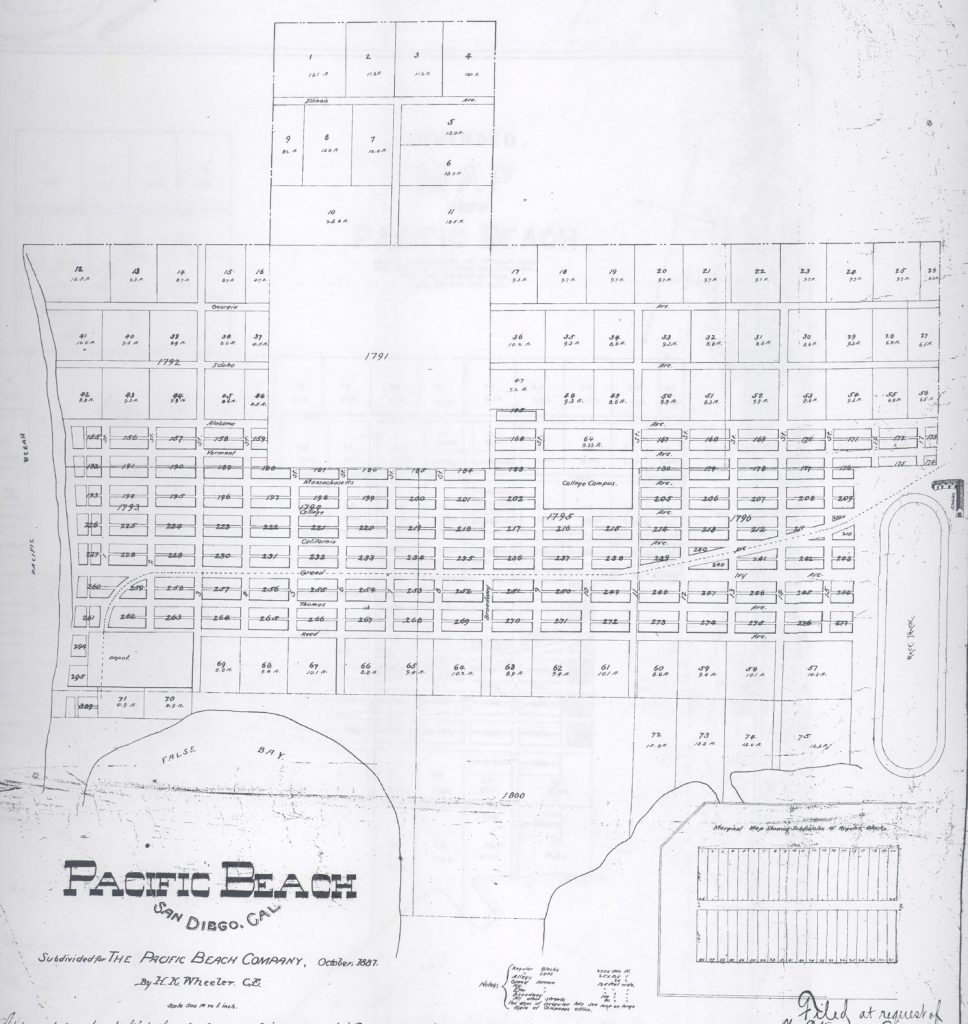

In 1887 a group of San Diego businessmen acquired most of the property north of Mission Bay (then called False Bay) and founded a community they christened Pacific Beach. Their Pacific Beach Company’s original subdivision map platted the entire area into residential blocks separated by streets (running north and south) and avenues (running east and west), with the widest avenue, Grand, also the route of a railway between downtown San Diego and a depot near the beach. The founders also set aside space for a college campus on what is now Garnet (then College) Avenue, between Jewell and Lamont (then 9th and 11th) streets, which they hoped would attract a nucleus of refined and cultured residents.

The San Diego College of Letters opened in 1888 and college students and their families were some of the first residents of Pacific Beach. Among the students were Edward and Theodore Barnes, Mary Cogswell, Evangeline and Mabel Rowe and Lulo Thorpe. The Barnes brothers’ parents, Franklin and Phoebe, moved to Pacific Beach in 1889 and bought several lots at the northwest corner of Lamont and Emerald (Vermont) streets, across Emerald from the campus, where they built a house. Dr. Thomas Cogswell was a dentist with a practice in downtown San Diego. He and his wife Elizabeth lived at the northwest corner of today’s Jewell and Diamond (Alabama) streets, a short distance from the college. Mary Rowe, mother of the Rowe sisters, had recently returned from India after her husband, a missionary there, died of typhoid. The Rowes lived in a house on the ocean front at the foot of Garnet. Lulo Thorpe’s mother was the then-famous poet Rose Hartwick Thorpe who had come to Pacific Beach to help establish the college. Lulo’s father, E. C. Thorpe, was a carpenter and building contractor.

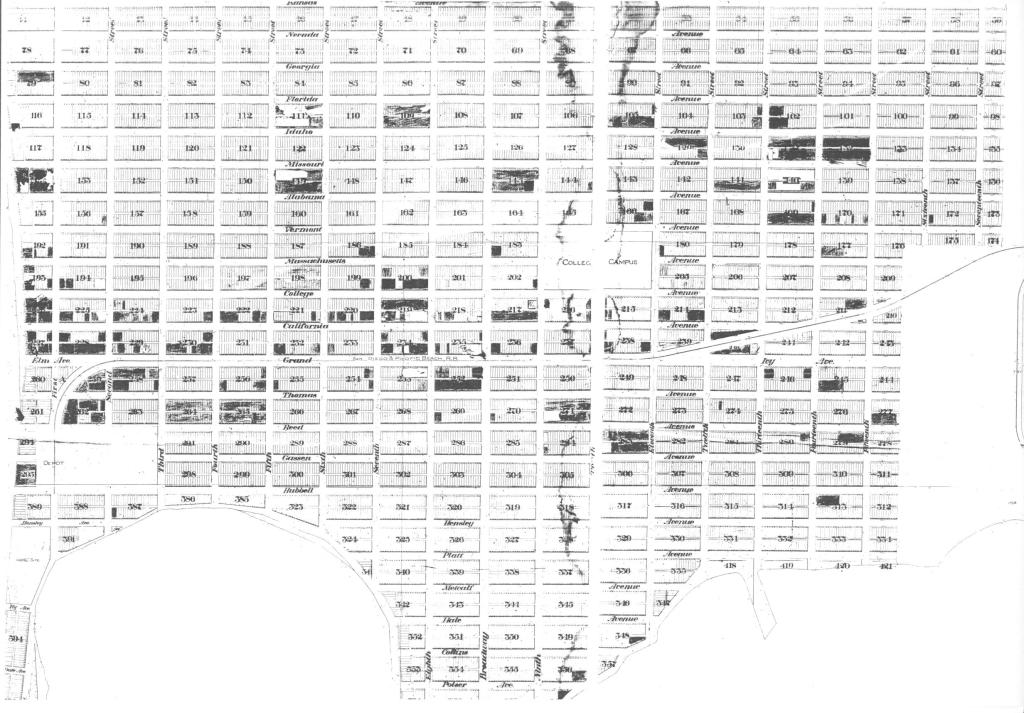

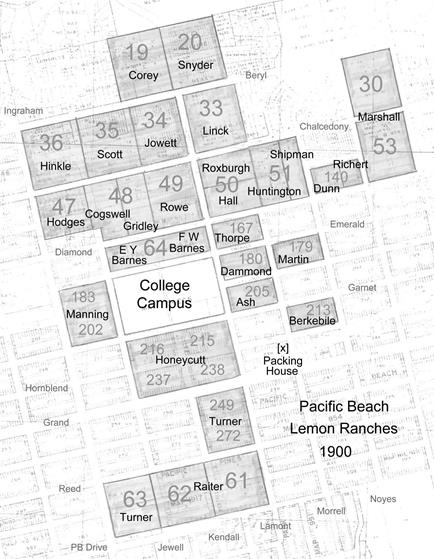

As an inducement to locate in Pacific Beach the founders had endowed the college with a number of city lots to be sold to finance its construction and administration. However, 1888 turned out to be the end of San Diego’s ‘great boom’ and despite several auctions held on the college campus few lots were sold. Unable to pay the architect’s construction bill the college closed in 1891 and most of the faculty and students moved away. With the departure of many residents and downturn in the residential real estate market the Pacific Beach Company reoriented its sales toward larger plots of land suitable for agrarian uses. An amended subdivision map was drawn up which eliminated many of the streets and avenues north of Diamond Street and south of Reed Avenue and transformed the former city blocks in these areas into ‘acre lots’ of about 10 acres. The amended map was recorded in January 1892 as map 697 (the numbered streets and state-themed avenues were renamed in 1900 to avoid conflicts with other numbered and state-themed streets in the city).

Writing for the San Diego Union in 1896, E. C. Thorpe recalled that by 1891 only three or four families remained from the college community but that the tract had then been placed upon the market as acreage property and in a few weeks a force of workmen were clearing the first hundred acres preparatory to planting lemon orchards — ‘Rabbits and rattlesnakes were driven back to mesa and canyon and the sunny southern slopes were soon clothed in fragrant lemon foliage’. The acre lots were sold for $100 an acre and one of the first to be sold was purchased by Franklin Barnes. Map 697 had incorporated his 8 lots at the corner of Lamont and Emerald into a larger acre lot 64, 9.3 acres enclosed by Lamont, Emerald, Jewell and Diamond streets, and in January 1892 he acquired the entire acre lot for $930. Mary Rowe bought acre lot 49, 8.6 acres west of Lamont Street between Diamond and Chalcedony (Idaho) streets, in April 1892 for $860. In 1893 she had her house moved from the ocean front to a location on her lemon ranch later to become Missouri Street. The Cogswells also acquired property for a lemon ranch, purchasing the western half of acre lot 48, 5.45 acres across Jewell Street from their home, for $545.

Altogether about a dozen purchases of acre lots on the ‘sunny slopes’ north of the college campus were recorded in the first half of 1892. Ida Snyder acquired acre lot 20, north of Beryl (Georgia) and east of where Lamont runs today (streets did not extend north of Beryl on Map 697). According to the Union Miss Snyder, of Omaha, immediately made arrangements to have her property put out to lemons. A contiguous group of 3 acre lots, lots 33, 34 and 50, which met at Chalcedony and Lamont streets, were sold to R. C. Wilson and G. M. D. Bowers from Tennessee in February. The Union reported that Wilson and Bowers, who had been business partners in Tennessee, were having 4,000 feet of water pipe laid over their thirty acre tract and that the property was to be put into lemons in the next few weeks. They also built houses on their properties, the Bowers family on acre lot 34, west of Lamont Street in 1892 and the Wilsons on lot 33, east of Lamont, in 1893. Wilson and Bowers also later purchased acre lot 51, north of Diamond and west of Noyes (13th) streets. Acre lots 19, 35, 36, 47 and the east half of acre lot 48, all north of Diamond Street, were also sold in the first half of 1892.

South of Reed Avenue, acre lot 61 was acquired in April 1892 by C. H. Raiter, a banker from Minnesota who had spent the winter in Pacific Beach. Mr. Raiter returned to Minnesota but left instructions to have his ten-acre tract put equally into lemons and oranges and to reserve a good building site. The property was to be piped, fenced and broken and planted as soon as possible. The Raiters never did build on their ranch but did add the adjoining acre lot 62 in 1894.

The acre lots were located in what were then undeveloped outlying areas of Pacific Beach but much of the land in more central areas of the community was also undeveloped and some city blocks in these areas were also turned into lemon ranches. The Thorpes purchased block 167, across Lamont Street from the Barnes ranch, in February 1892 for $466 or $150 an acre. Sterling and Nancy Honeycutt bought lot 205, across Lamont from the college buildings and the four blocks around the intersection of Hornblend and Kendall streets in 1893 for a lemon ranch. J. L. Holliday acquired a pair of adjacent blocks between Garnet Avenue and Ingraham (then Broadway), Emerald and Jewell streets, blocks 183 and 202, and set them to lemons in 1895. The Holliday lemon ranch was sold to Nathan Manning in 1898.

E. C. Thorpe reported from Pacific Beach in 1894 that ‘Lemons do nicely here, and Pacific Beach expects much from its future lemon culture’. He noted that Pacific Beach had a great diversity of soil and that the sandy soil nearer the bay was not considered as valuable as the heavier soil on higher lands where the trees make the best growth and require less water. In March 1894 Frank Marshall of Kansas City bought two ten-acre lots in these higher lands, paying $2150 or $150 an acre for acre lots 30 and 53, 8.6 acres each between Diamond and Beryl and east of Olney (14th) Street. According to the San Diego Union he had plowed, piped and planted 1400 lemon trees and a hedge of Monterey cypress would be set out all around his land as a windbreak. He had returned to Kansas City but would come back in the fall with his brother and each would build a handsome residence. In his absence the ranch would be managed by Edward Barnes.

Mr. Marshall did not come back in the fall of 1894 but did return in June 1895 and built a handsome residence on acre lot 30 where he lived with his wife May. His brother, T. B. Marshall, finally arrived in Pacific Beach in January 1895 and in April moved into a handsome residence on acre lot 53 that the Union’s correspondent called the ‘finest in our colony’. Frank Marshall’s brother-in-law Victor Hinkle also followed in December 1895 — Carrie Hinkle was May Marshall’s sister; the couples had been married on the same day in 1889. In February 1896 the Hinkles purchased acre lot 36, 10.2 acres lying between Chalcedony, Ingraham, Beryl and Jewell streets, paying Alzora Haight $2000 or nearly $200 an acre for what was then a developed lemon ranch. Although the Haights had owned acre lot 36 since 1892 they had ‘camped’ on the property rather than building a house and the Hinkles had another fine residence built there in 1896.

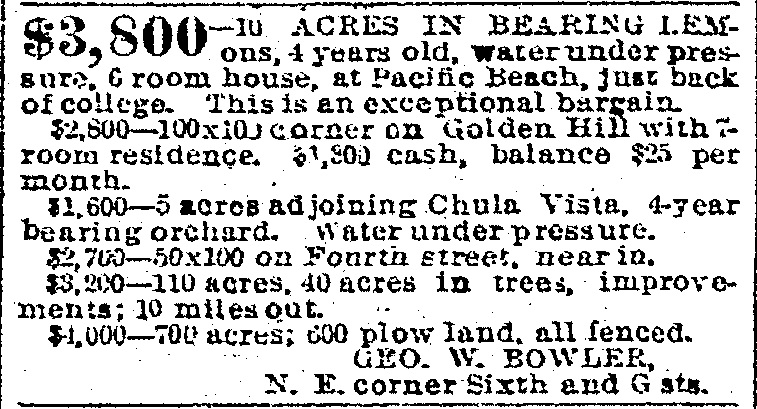

In 1895 the Wilson and Bowers families decided to move back to Tennessee and put the four acre lots of their lemon ranch up for sale. The eastern 3.5 acres of lot 51 had been sold for $500 in 1894 but between September and November of 1895 they sold lot 33 to Ozora Stearns and lot 34 to William Davis for $5500 each, lot 50 to Lewis and Elizabeth Coffeen for $3000 and the western five acres of lot 51 to B. F. Colvin for $1000 (lots 33 and 34 each came with houses while lots 50 and 51 were unimproved). The Coffeens had a house built on acre lot 50 and had moved in by December but when they were compelled to return east for business reasons in 1897 their 10 acres in bearing lemons with water under pressure and a 6 room house was sold to Maj. William and Henrietta Hall.

The Franklin Barnes family lived in a house at Lamont and Emerald streets, at the southeast corner of their lemon ranch in acre lot 64. In 1895 their son Edward built another house at the southwest corner of lot 64, the corner of Jewell and Emerald, which he named El Nido (the nest). Also in 1895, E. C. Thorpe and his family moved into the house he built on block 167, across Lamont from the Barnes and named Rosemere Cottage for his wife Rose Hartwick Thorpe. In July 1895 the Thorpes’ daughter Lulo and Edward Barnes were married at Rosemere and moved the two blocks west to El Nido. In 1896 ownership of El Nido and the west half of acre lot 64, 4.5 acres, was transferred to Edward and Lulo Barnes.

Also in 1896, Edward Barnes built the first lemon curing house in Pacific Beach. Tree-ripened lemons tended to be too large and were graded down by commercial buyers. Better grades and prices could be obtained by picking the lemons before they were fully grown, and still green, then ‘curing’ them for 30 – 60 days until they reached a lemon-yellow color. Cured lemons not only had a more acceptable and uniform appearance but also thinner rinds and better keeping qualities. In January 1897 the San Diego Union reported that Mr. Barnes had picked 72 boxes of lemons in December alone from 280 4-year-old trees and that for the year his yield had been 1,200 boxes, netting $1 per box (a box held about 40 pounds of lemons).

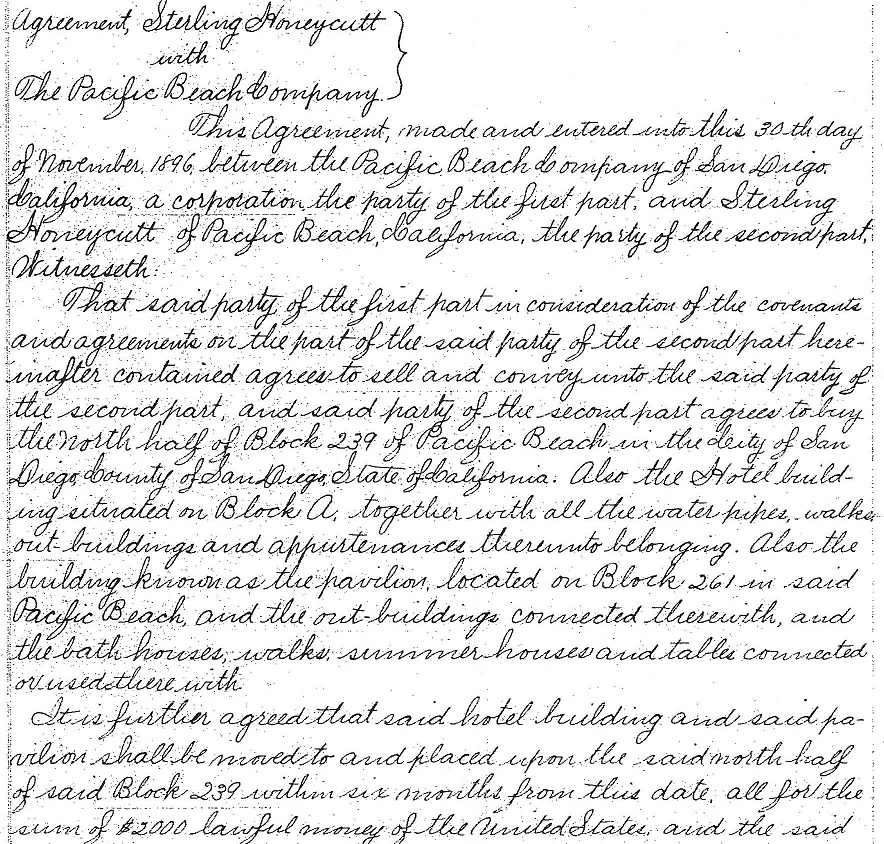

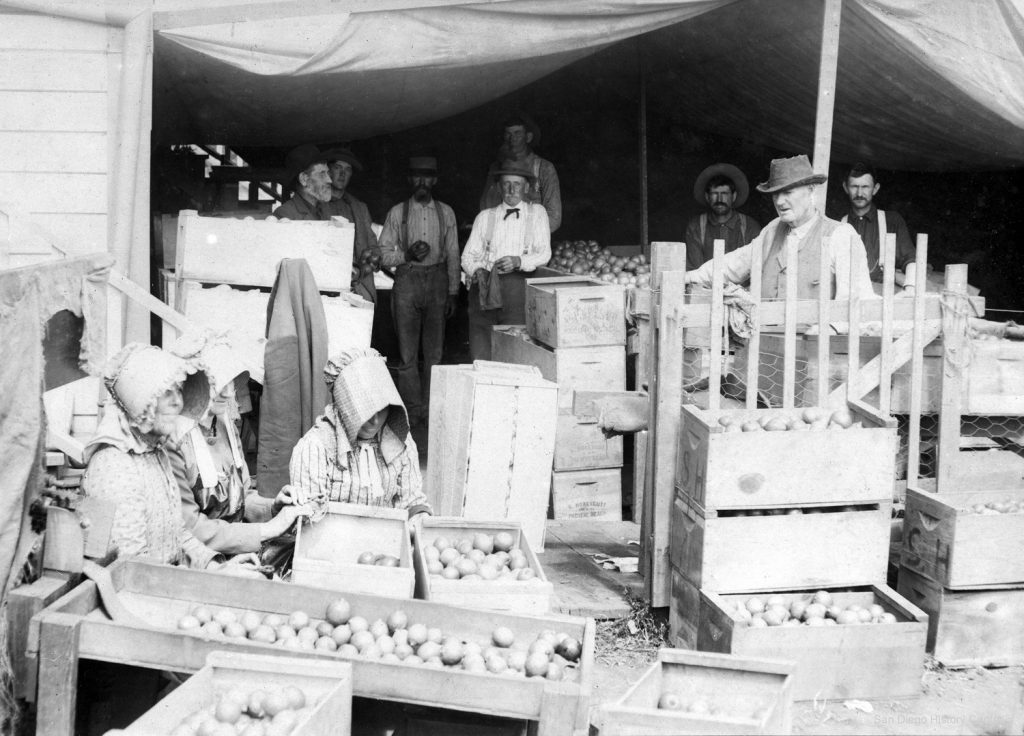

In 1888 the Pacific Beach Company had built a hotel and dance pavilion near the railroad depot at the foot of Grand Avenue but neither had been very successful. In 1896 they were sold to Sterling Honeycutt with the provision that they be moved to property he had purchased in block 239, the south side of Hornblend between Lamont and Morrell streets and adjacent to his lemon ranch. The move was completed in early 1897; the hotel was set down on the southeast corner of Hornblend and Lamont streets and the pavilion on the southwest corner of Hornblend and Morrell. At the time the railroad between Pacific Beach and downtown San Diego ran over Grand Avenue from the depot near the beach to Lamont Street, where it turned toward the northeast on what is now Balboa Avenue, passing close to the new location of the pavilion (the raised ‘island’ in the center of these streets was once the railroad right of way). Mr. Honeycutt and other lemon ranchers including Franklin Barnes and Frank Marshall turned the pavilion into a lemon curing and packing house and the railroad added a siding where boxcars could be parked while being loaded with boxes of lemons. On August 13, 1897, the Evening Tribune reported that Pacific Beach reached an important event in its history when the first full carload of lemons loaded in Pacific Beach was shipped east, directly to Duluth. Later in 1897 Honeycutt sold the property, with the ‘most commodious packing and curing house in the county’, to Barnes and Marshall. Edward Barnes was placed in charge of packing and shipping and initially shipped from 75 to 100 boxes of lemons weekly.

In February 1898 Franklin Barnes reported that there were about 25,000 lemon trees in bearing and that during 1897 he had picked 1,400 boxes from 600 trees and was then picking from the same trees 200 boxes per month. The leading varieties were Lisbon, Villa Franca and Eureka and about 7,000 boxes were shipped in the last year. Mr. Barnes was also a featured speaker when the County Horticultural Society met in October 1898 at Stough Hall, a former college building and then the principal meeting place in Pacific Beach (the front of the stage had been very prettily decorated with festoons of lemons). He told the delegates that his expenses for cultivation and water had averaged $200 a year for five years and that the orchard had paid over $1000 the previous year.

Many participants in the Pacific Beach lemon industry were women. Mary Rowe, Martha Dunn Corey and Ida Snyder had been among the first purchasers of acre lots in 1892. The San Diego Union noted in 1897 that Mrs. Rowe’s ranch had been developed from the raw condition to one now valued at $9000 and that the ladies of Pacific Beach were justly proud of their ranches. William Davis, who purchased the lemon ranch on acre lot 34 in 1895, was a mining engineer who spent much of his time at the Arizona mines leaving the ranch in the hands of his sister Louise. The Union reported in June 1896 that Miss Davis had shipped 84 boxes of choice lemons from Ondawa ranch (many ranchers in Pacific Beach gave their ranches names). Ozora Stearns had purchased the ranch in acre lot 33 in 1895 but he died in 1896 leaving it to his widow Sarah. Their eldest daughter married in 1897 and her husband John Esden took over operation of the lemon ranch, making improvements including what the Union called an ‘up-to-date curing house’. J. D. Esden & Co. became one of the largest lemon producers in Pacific Beach, shipping carloads of lemons in 1898. When acre lot 33 was sold again in 1899 the buyer was also a woman, Carrie Belser Linck, and her son Charles Belser assumed management of the ranch and the curing and packing operation.

Maj. William Hall, who had acquired the lemon ranch in acre lot 50 in 1897, was the author of the San Diego Union’s New Year’s Day report from Pacific Beach in 1900. According to Maj. Hall about three hundred acres of lemon groves from three to seven years old and from 2 ½ to 10 acres were clustered at the center of this beautiful spot, dotted here and there with fine residences with well kept yards, beautiful with every variety of flowers and in bloom all year round. The Pacific Beach lemon groves were not only attractive but productive; during the past year thirty carloads of lemons (and two of oranges) had been raised and shipped (a carload was about 600 boxes, or twelve tons of lemons). A few months later, in July 1900, Maj. Hall profited by selling a portion of his investment in this beautiful spot, the north half of acre lot 50, ‘with 12 rows of trees running east and west’, to Alfred and Margaret Roxburgh for $2500. After a few years living in houses on neighboring lemon ranches the Roxburghs built a home on their own ranch in 1904, described by the Evening Tribune as both substantial and artistic looking, being built largely of stone.

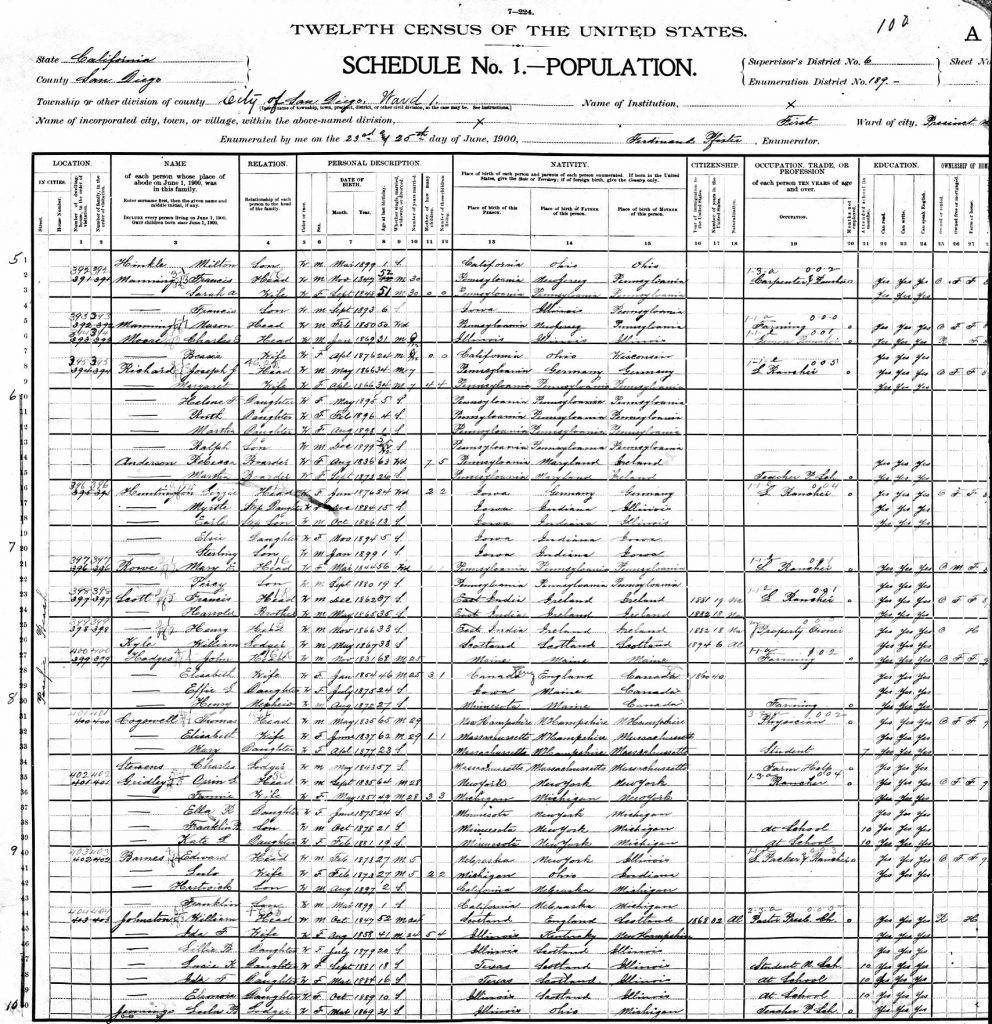

An enumerator for the United States census visited Pacific Beach in June 1900 and counted a total of 54 dwellings and 185 residents. For the ‘head of the family’ in each of these dwellings the ‘occupation, trade or profession’ column listed twelve as ‘Lemon Rancher’ (or ‘L. Rancher’) and two more as ‘L. Packer and Rancher’ (F. W. and E. Y. Barnes). Lemon rancher Francis Manning was listed as ‘Carpenter and Rancher’ and E. C. Thorpe was a ‘Contractor and Rancher’. Dentist Thomas Cogswell and Dr. Martha Dunn Corey were both listed as ‘Physician’, but both also owned lemon ranches. Some family heads listed as ‘Rancher’ (Gridley), ‘Farmer’ (Williams) or ‘Farming’ (Hodges) and some with no occupation listed (Conover) were also actually lemon growers. Two other heads were listed as working in packing houses. Other family members and lodgers in these dwellings included a packing house laborer and farm laborers and farm help, some of whom presumably labored or helped on lemon ranches. Altogether at least 23 of the 54 households counted in the 1900 census in Pacific Beach were involved in the lemon business.

1900 may have been the lemon industry’s best year in Pacific Beach. Reports from Pacific Beach in the Evening Tribune invariably described the activities of lemon ranchers and packers in superlative terms. Belser and Co. lemon packers were doing a land office business, shipping cars east at the rate of two a week. F. W. Barnes and Son shipped two carloads of lemons one week. The price of lemons has reached a point where growers will soon be wearing diamonds and saying ‘ither and nither’. However, some growers apparently were not as convinced about the future of the lemon business. The Snyder lemon orchard was for sale at less than half cost, Maj. Hall had sold half of his ranch to the Roxburghs and Sterling Honeycutt sold one of his five-acre lemon ranches to Mr. McConnell. In December 1900 Frank Marshall sold his ranch in acre lot 30 and also his half interest in the packing house at the former pavilion to R. M. Baker.

Mr. Baker continued his acquisitions of lemon properties in 1901. In January he bought out Franklin Barnes’ half interest to become sole owner of the packing house (Barnes had been elected to the California state assembly and took office on January 1). In March 1901 the news was that the packing house had been running full handed since it changed ownership and was handling lemons by the ton as the lemon trees were bearing wonderfully; a dozen carloads were packed waiting for cars. Mr. Baker also bought the other Marshall lemon ranch on acre lot 53 and the southern half of Maj. Hall’s ranch in acre lot 50.

Although the lemon trees were ‘bearing wonderfully’ the Tribune also noted that the price of lemons stayed in the depth because of cold weather in the east and importation of foreign lemons which, in the words of its correspondent, were ‘loaded with the germs of bubonic plague and delirium tremens’. In July they were selling for 2¢ a pound, which would be about 80¢ for a 40 pound box, down from $1 a box in 1896. The turnover of the ownership in lemon ranches continued into 1902 as the Raiters sold their ranch in acre lots 61 and 62 in April and the Gridley five-acre lemon ranch on the east half of acre lot 48 was sold to ‘eastern people’ for $5500 in July. Still, the Baker packing house was shipping two cars a week and the Tribune added that a class in physical culture had been started that would get the muscles in fine shape for picking lemons. One grower was trying out a new market, paying $5 a box freight in advance to ship lemons to the Klondike. The papers speculated that he would need to get a good-sized nugget for every lemon shipped. Edward Barnes was trying out a new crop, putting out several thousand tomato plants on the old Snyder ranch on the hill.

The packing house was still running full-handed in 1903 and the February and March crop of lemons were said to be simply immense; Mr. Baker had picked from his lower ten-acre ranch 1600 boxes at 40 pounds a box or 64,000 pounds of lemons, which the Union called the record picking off a ten-acre ranch so far (Baker’s lower ranch, presumably meaning in elevation, was acre lot 53). Recent rains had made the fishing in False (Mission) Bay very good and ‘that attraction was keeping anglers busy when not employed in the orchards’. Still, ‘lemon prices not all that could be wished for’ and in November 1903 Mr. Baker sold the packing house to Sterling Honeycutt. The new packing house firm, Honeycutt & Pike, was doing business at the Honeycutt Hotel building and had shipped a carload of lemons to Kansas City.

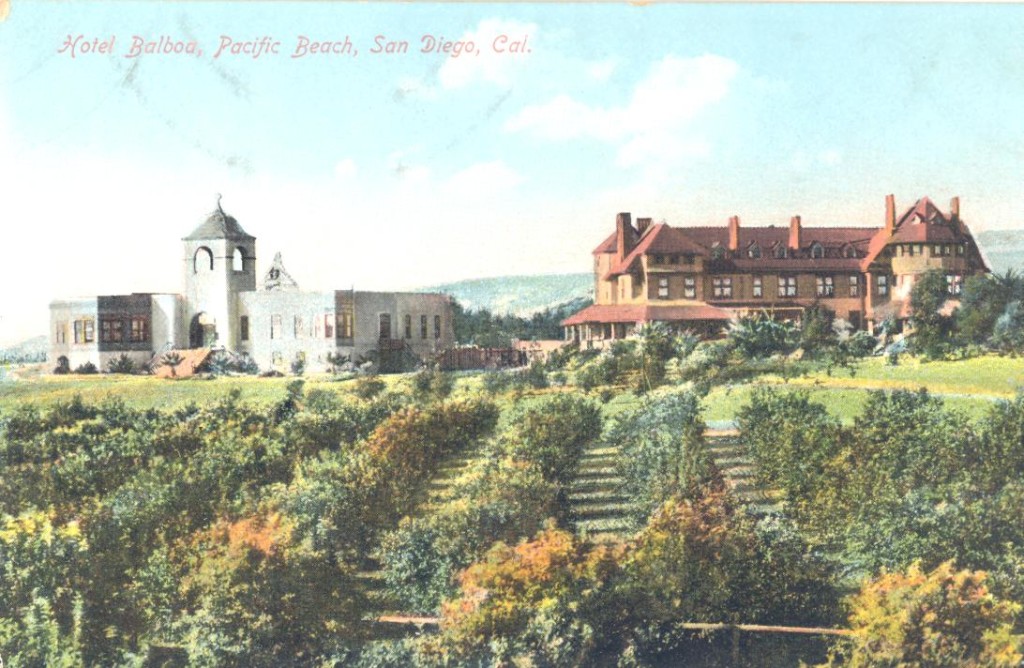

The lemon business that had sustained Pacific Beach for the decade after the college failed in 1891 continued to decrease after 1903. Markets for lemons were mostly in the East where lemons from foreign sources, particularly Sicily, could often be delivered at lower cost and undercut growers on the west coast. In Pacific Beach the diminished profits from lemon cultivation also coincided with a resurgence of residential development, providing an incentive for lemon ranchers to turn their acreage property back into building lots or to sell it to real estate operators. One major operator, Folsom Bros. Co., had acquired much of Pacific Beach in 1903 and implemented improvements like grading streets and pouring concrete sidewalks to stimulate sales to potential home buyers. Folsom Bros. also purchased and refurbished the college and reopened it as a resort hotel, the Hotel Balboa. There were persistent rumors that the steam railroad would be upgraded to a fast electric line, improving access to downtown San Diego (in 1907 the route was shortened and straightened to run over today’s Grand instead of Balboa Avenue east of Lamont Street, but it was never electrified).

Sterling Honeycutt was one lemon rancher who made a successful transition into the real estate business. His lemon ranch had been located on the four city blocks around the intersection of Hornblend and Kendall streets. In 1901 he sold block 216, north of Hornblend and west of Kendall, and by 1904 several houses had been built on the north side of Hornblend Street in this block. In 1903 Honeycutt also sold block 238, south of Hornblend and east of Kendall, to William Pike and Pike built his home on the south side of Hornblend. In 1904 Honeycutt sold Pike block 237, south of Hornblend and west of Kendall, and also sold several lots in block 215, north of Hornblend and east of Kendall, where more houses were built along Hornblend. In less than five years Hornblend Street went from lemon ranch to the first residential neighborhood in Pacific Beach, and some of these first homes can still be seen. In 1905 Pike sold the western quarter of block 237 to Charles Boesch and in 1906 Boesch built the house at the southwest corner of his property, Grand Avenue and Jewell Street, that is still standing and was restored in 2021.

Honeycutt’s brother-in-law W. P. Parmenter and the Parmenters’ sons-in-law Charles and Frank McCrary moved to Pacific Beach in 1903 and were also involved in making former lemon ranches into residential homesites. In December 1903 Frank McCrary purchased Edward and Lulo Barnes’ lemon ranch and their home, El Nido, on the west half of acre lot 64. Edward Barnes had opened a store at the corner of Grand Avenue and Lamont Street and had transitioned from the lemon business to storekeeping; his family had moved into the Thorpes’ home on block 167 after the Thorpes moved to La Jolla where E. C. Thorpe was busy building houses (in 1906 the Edward Barnes family moved again, leaving Pacific Beach for 4th and Upas streets in San Diego where Assemblyman Franklin Barnes had moved the previous year).

Parmenter and Charles McCrary also acquired block 213, the lemon ranch of John Berkebile between Garnet Avenue and Noyes, Hornblend and Morrell streets. Parmenter sold the north half to Madie Arnott Barr, another major Pacific Beach real estate operator, and McCrary sold the south half to H. J. Breese, who in 1904 built the home still standing at the northeast corner of Morrell and Hornblend (in the 1920s this property became the site of H. K. W. Kumm’s passion fruit ranch). Also in 1904, Parmenter and Frank McCrary purchased acre lot 20, formerly the Snyder lemon ranch, northeast of Lamont and Beryl streets. They passed it on to Honeycutt who in 1906 had it subdivided, returning it to its original configuration as blocks 53 and 66 of Pacific Beach. In 1907 Andrew and Ella MacFarland bought corner lots in block 66, at Lamont and Beryl streets, and built the classical revival home still there today.

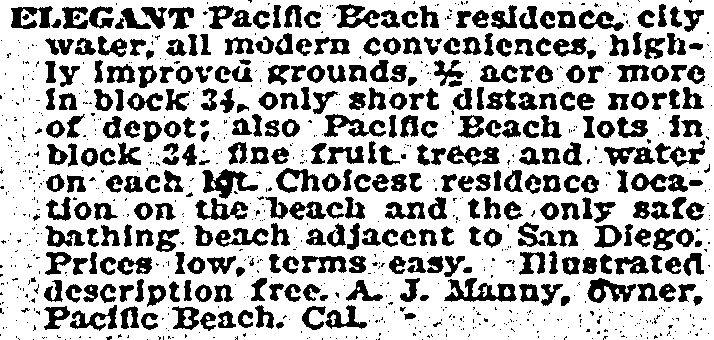

Former lemon ranches on acre lots 35 and 34 were also re-subdivided into city blocks with their original block numbers. The Scott brothers were from England and since 1895 had grown lemons on acre lot 35, between Chalcedony, Jewell, Beryl and Kendall streets (they also had a lemon ranch in Chula Vista) and they subdivided it as blocks 89 and 106 of Pacific Beach (and Kendall and Law streets) in 1904. Acre lot 34 had been part of WIlson and Bowers’ original lemon ranch and had since been owned by the Davis, Jowett and Boycott families and, since 1903 the Mannys. On New Year’s Day in 1907 an advertisement appeared in the San Diego Union for an elegant Pacific Beach residence and also lots in the choicest residential location of Pacific Beach, with fine fruit trees and water on each lot, all in acre lot 34. The entire acre lot was purchased four days later by Robert Ravenscroft and in October 1907 Ravenscroft had it subdivided as blocks 90 and 105 of Pacific Beach (and an 80-foot strip between them for Law Street). After Mary Rowe sold her lemon ranch on acre lot 49 to John and Julia Hauser in 1903 the Hausers also subdivided it into two blocks identical to what had appeared on the original 1887 Pacific Beach map. The street between the two blocks was even derived from the original map’s Missouri Avenue. However, their subdivision was officially recorded in 1904 as Hausers Subdivision of Acre Lot 49.

Other acre lots were not subdivided but instead were sold off piecemeal as homesites. In 1906 Sterling Honeycutt bought the east half of acre lot 48, excepting the southeastern corner where E. C. Thorpe had built a ranch house for Orrin and Fannie Gridley in 1896. The Gridleys had left in 1902 and their five-acre lemon ranch had since been owned by J. W. Stump. Strips of land were reserved and dedicated to the city for Missouri Street and two alleys and the remainder divided into parcels of various sizes for building lots. The southeast corner lot and house was offered for sale in 1907 for $4000. That house stood at 1790 Diamond Street (next door to where I grew up) until it was demolished in 1968.

Most of acre lot 50 was also never subdivided and lots there are still described in terms like the east 50 feet of the west 150 feet of the south 135 feet of acre lot 50. A strip of land 52 feet wide between the northern and southern portions of the lot was granted to the city in 1916 for an extension of Missouri Street. The portion on the south side of Chalcedony Street was subdivided as Picard Terrace in 1950.

In 1904 Estes and Margaret Layman, from Des Moines, Iowa, paid $15,000 for the lemon ranch in acre lot 33 (and changed its name to Seniomsed, Des Moines spelled backwards). This ranch had always been one of the most productive in Pacific Beach and the Laymans continued that legacy, at least for a few more years. In 1906 the Union reported that Mrs. Layman was ‘busy as a bee in a tar barrel’, picking, packing and shipping a carload of lemons (to Des Moines). However, that carload of lemons may have been the last shipped from Pacific Beach, and later that year the landmark pavilion building which had been the main lemon packing plant since 1897 was closed. Many of the lemon ranchers were Methodists and their congregation had outgrown the ‘little chapel’ then in use. Sterling Honeycutt was a founding member of the Methodist church and he also owned the packing plant, which had been experiencing a decline in business. In August 1906 he donated the building and the five lots surrounding it to the church under the condition that $2000 should be raised to cover the necessary alterations. By September the news was that the great building known for so long as the packing house was rapidly assuming the graceful lines and sober colors of a church. The handsome new structure was dedicated in February 1907.

Transition of the former lemon ranches into housing developments occurred over many decades and was not complete until the 1950s, and a few continued with agrarian activities in intervening years. Victor Hinkle turned acre lot 36 into a general farm and also specialized in beekeeping. The former ranch houses in acre lots 33 and 50 were rented to Japanese families who operated truck farms on the fertile land there. Others were subdivided when Pacific Beach experienced periods of population growth in the 1920s and again in the 1940s. Kendrick’s subdivision of acre lot 47 occurred in 1925, and Pacific Pines on acre lots 61 and 62 and C. M. Doty’s Addition on acre lot 19 were subdivided in 1926. Portions of acre lot 36 became Chalcedony Terrace and Chalcedony Terrace Addition in 1947, although the portion that actually fronts on Chalcedony was not included and lots there are still described as portions of acre lot 36. 1947 was also the year that acre lot 33 became part of the Lamont Terrace development. In 1941 most of Pacific Beach east of Olney Street, including the former Marshall and Baker ranches in acre lots 30 and 53, was expropriated by the federal government for the Bayview Terrace housing project. Most of this property remains under government ownership, now known as the Admiral Hartman Community.

In 1910 the census enumerator again made the rounds of Pacific Beach. This time there were more than twice as many residents counted but none mentioned lemons in their occupation, trade or industry, or in the general nature of their industry or business. Instead, the pendulum had swung decidedly from lemon ranching toward residential development. Ten residents were described as real estate agents, including Sterling Honeycutt, eleven listed contractor, carpenter or stonemason as their trade, and building or houses as the general nature of their business, and another five were concrete or cement workers in the ‘street’ business. Of the few former lemon ranchers still living on their ranches Victor Hinkle was listed as a farmer and E. H. Layman as ‘own income’.

The 1910 census was held in April; just a few months later, in November 1910, Capt. Thomas A. Davis leased the Hotel Balboa and turned the former college campus back into an educational institution, this time as a military academy. Beginning with 13 cadets and himself as the only instructor Capt. Davis’ San Diego Army and Navy Academy grew steadily. In 1922 he expanded the campus into the former lemon ranches in acre lot 64 to the north and blocks 183 and 202 to the west for athletic fields and a parade ground. The former homes of the Franklin and Edward Barnes families were put to use as residences for academy staff. In 1924 Davis’ brother John also purchased the former Thorpe home across Lamont Street in block 167 and the Davis’ mother lived there into the 1950s. The academy, later called Brown Military Academy, also survived into the 1950s until it too declined and was turned into a shopping center.

The lemon trees and packing plant have been gone for over a century but there are still signs of the lemon era to be found in Pacific Beach. On what was once Wilson and Bowers’ lemon ranch around the corner of Chalcedony and Lamont streets the Bowers’ original house on acre lot 34, built in 1892, is still standing at 1860 Law Street (although it was moved from its original location on the other side of Law in 1912). In acre lot 50, also once part of the Wilson and Bowers ranch, the house built by the Coffeens in 1895 remains at 1932 Diamond and the Roxburghs’ home from 1904 is on the alley at 4775 Lamont. When acre lot 33 was cleared in 1947 to make way for the Lamont Terrace development the only thing spared from the former Wilson ranch house there was the Moreton Bay fig tree still growing between 1904 and 1922 Law. A Moreton Bay fig spared by developers of the Bayview Terrace (1941) and Capehart (1960) housing projects is also the only sign of Frank Marshall’s ranch in acre lot 30, now the corner of Chalcedony and Donaldson Drive. A palm tree between apartments at 1828-1840½ Missouri once stood in front of Mrs. Rowe’s ranch house in acre lot 49. And the house built by the Hinkles on acre lot 36 in 1896 was moved in 1926 across Ingraham Street to where it now stands at 1576 Law Street.

The lemon era in Pacific Beach is also recalled in less tangible forms. In 1895 a group of women including Rose Hartwick Thorpe, Phoebe Barnes and Elizabeth Cogswell formed the Pacific Beach Reading Club. The club was initially led by Mrs. Thorpe and met at the homes of club members, most of which were lemon ranches at the time. After Sterling Honeycutt sold a portion of his lemon ranch to William Pike and Mr. Pike sold the western quarter of his portion to Charles Boesch, Mr. Pike and Mr. Boesch, whose wives were both Reading Club members, donated the two lots on Hornblend Street where their properties met for a clubhouse. Workers donated free labor, Mr. Pike, the former lemon packer, supervised construction, and the clubhouse had its formal ‘housewarming’ in October 1911. Club members had always been women and it became known as the Pacific Beach Woman’s Club, a name that was officially adopted in 1929. The club is still active, although the lemon-yellow clubhouse at 1721 Hornblend was sold in 2021, and the heritage of its lemon-ranching founders is commemorated in its lemon-themed website.