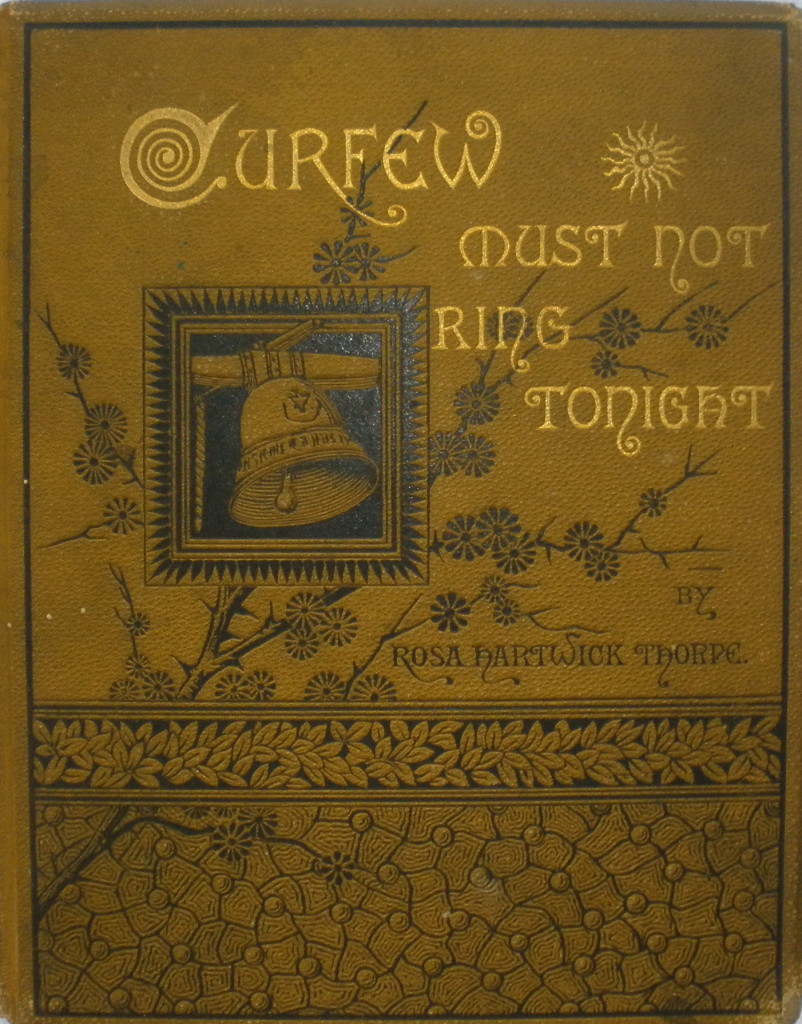

Edmund Carson (E. C.) Thorpe was born in Ohio in 1849 and by 1871 was working as a carpenter making wagons and carriages in the town of Litchfield, Michigan. He was also an aspiring writer and entertainer, composing and performing humorous recitations in a ‘German dialect’ style. In 1871 he married Rose Hartwick, also a writer, who had already achieved literary fame with her world-renowned ballad ‘Curfew Must Not Ring Tonight’, written while still a schoolgirl at Litchfield. After their marriage, Rose Hartwick Thorpe continued writing, and occasionally publishing, her poetry and ‘Ned’, as she called him, continued building wagons and carriages in Litchfield. Their daughter Lulo was born there 1873 and they later lived in Chicago, Grand Rapids, Michigan and then San Antonio, Texas, where they moved for his health in the 1880s.

The Thorpes were still in Texas in 1887 when Mrs. Thorpe was invited by Harr Wagner, editor and publisher of the San Diego-based literary magazine Golden Era, to help him establish San Diego’s first college. She accepted and the September 4, 1887, edition of the San Diego Union noted that the author of ‘Curfew Must Not Ring’ and her husband had arrived and would relocate in this city. A month later the Union reported that the Golden Era for October would contain ‘First Impressions of San Diego’ by Rose Hartwick Thorpe. In November, when the Golden Era company incorporated in San Diego (it had previously been published in San Francisco), E. C. Thorpe became a director and shareholder.

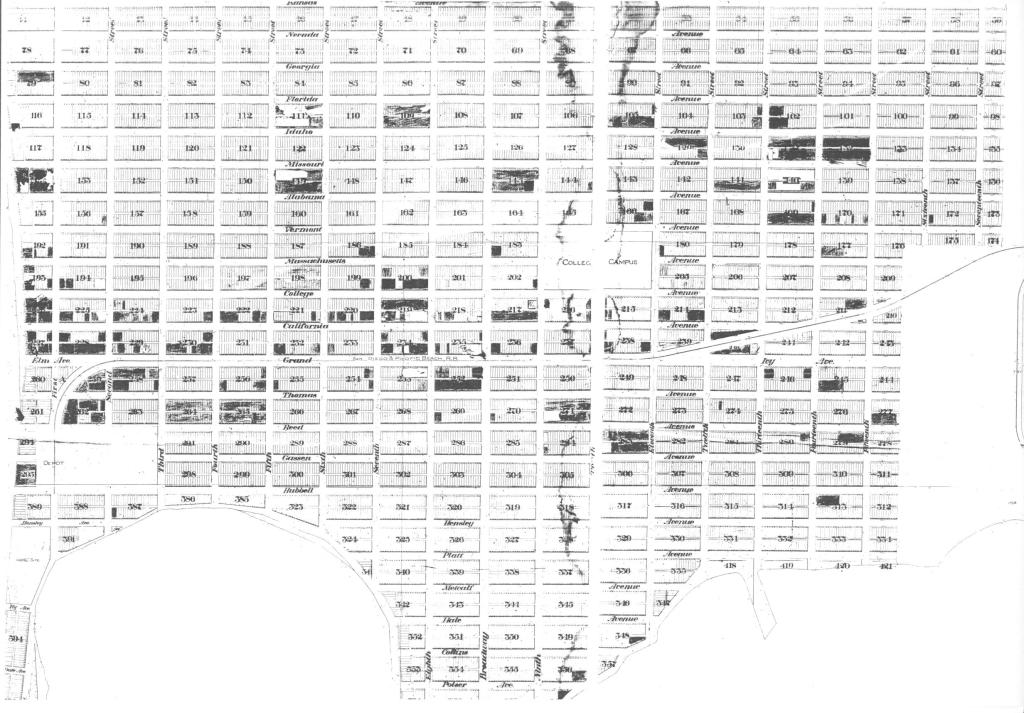

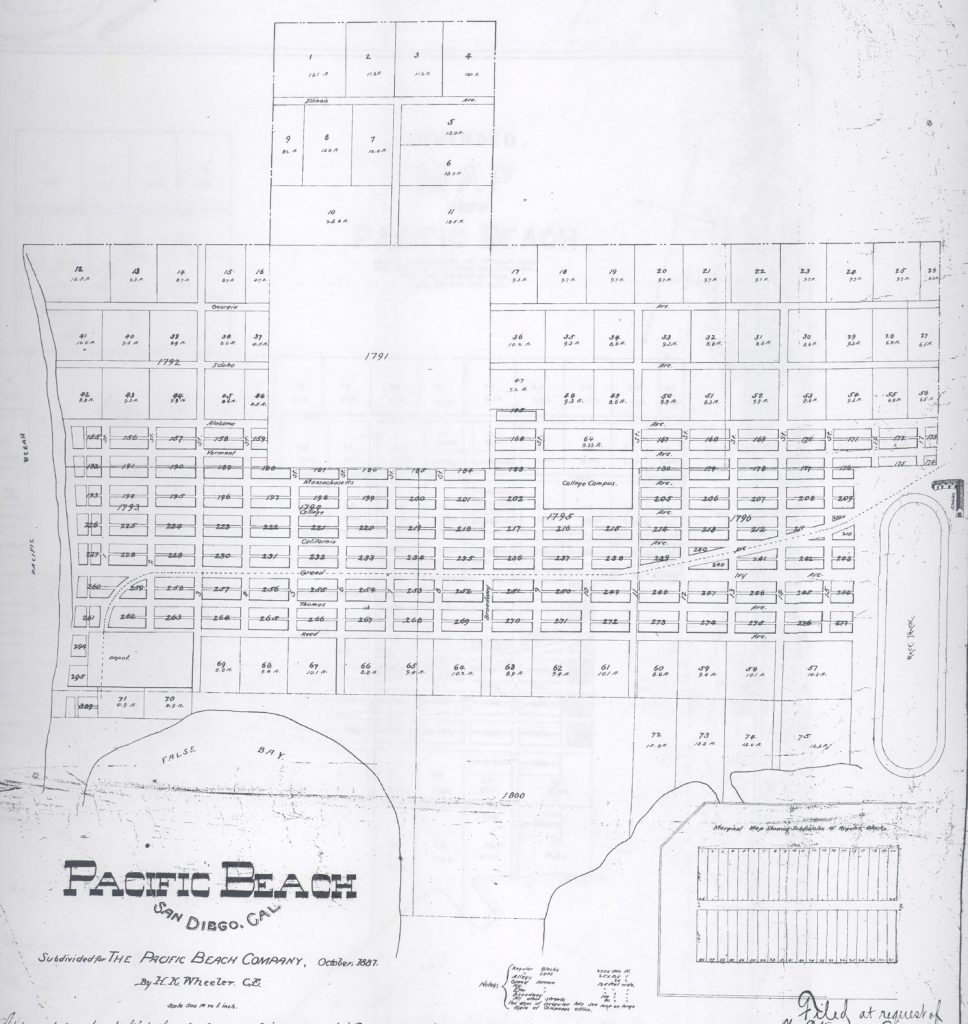

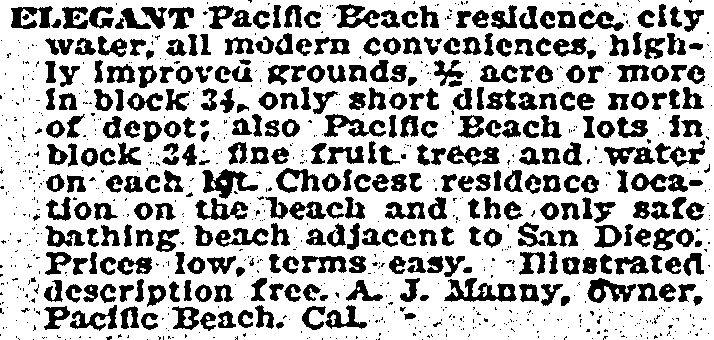

In 1887 San Diego was in the midst of a housing boom following the completion of a transcontinental railway link in 1885 and the influx of thousands of would-be residents. E. C. Thorpe participated in the boom by becoming agent for a company which provided small portable houses that could be taken down and set up in another location. San Diego’s ‘great boom’ also encouraged real estate developers to establish subdivisions in the previously uninhabited areas north of the San Diego River, including Pacific Beach and La Jolla. The developers of the Pacific Beach subdivision offered Harr Wagner a site for his college, a four-block campus in the heart of their community that is now the Pacific Plaza shopping center, and construction of the San Diego College of Letters began with the ceremonial laying of a cornerstone on January 28, 1888. In May 1888 the Thorpes bought a lot about a block away from the college campus (for $275) and set up a portable house on it, making them ‘the very first settlers’ of Pacific Beach according to Mrs. Thorpe. They soon bought additional lots adjoining their original purchase and Mr. Thorpe built a more substantial home there. When the college opened in October 1888 Lulo Thorpe was one of the 15 young ladies and 22 young men making up its inaugural class.

During their early years in San Diego the Thorpes also cultivated a sideline as entertainers, appearing together at ‘entertainments’ where Mrs. Thorpe would read selections from her works, especially ‘Curfew’, and Mr. Thorpe, assuming the character of ‘Hans’ and speaking the ‘broken English of a Dutchman’, would perform recitations like ‘Dot Bacific Peach Flea’ (‘Vot shumps und viggles und bites . . . Und keepen me avake effry nights’). While some entertainments were casual affairs put on for the local community, others were in front of paying audiences downtown or in other cities. In March 1890 the Union announced one such entertainments at which E. C. Thorpe (Hans) would read some of his own inimitable productions, one of which the Union had published earlier and was the first of his works to appear in print (‘The Union takes considerable pride in having introduced “Hans” to the reading public’). Rose Hartwick Thorpe, who was ‘too well known throughout the length and breadth of this land to need a single word of comment’, would read her ‘Curfew’ as well as some newer pieces. In its review a few days later the Union reported that nearly every seat was filled with some of the most prominent people in San Diego and the gifted litterateurs charmed the hearts of their hearers from first to last. “Hans”, as usual, convulsed his audience with laughter and the famed authoress won her listeners with her own spirited compositions including ‘The Fair God, San Diego’, a gem read for the first time and never before published.

E. C. Thorpe’s appearances before crowds of prominent people may have been a factor in his election to San Diego’s Board of Delegates in April 1891. He was one of four candidates for the First Ward, everything within the Pueblo boundaries north of Upas Street and north and west of San Diego Bay, which included Old Town, La Playa, Pacific Beach and La Jolla. Two delegates were elected from each of the city’s nine wards and in the First Ward Mr. Thorpe received the most votes, 95, out of 325 cast. He served a single term and did not run again in the 1893 election.

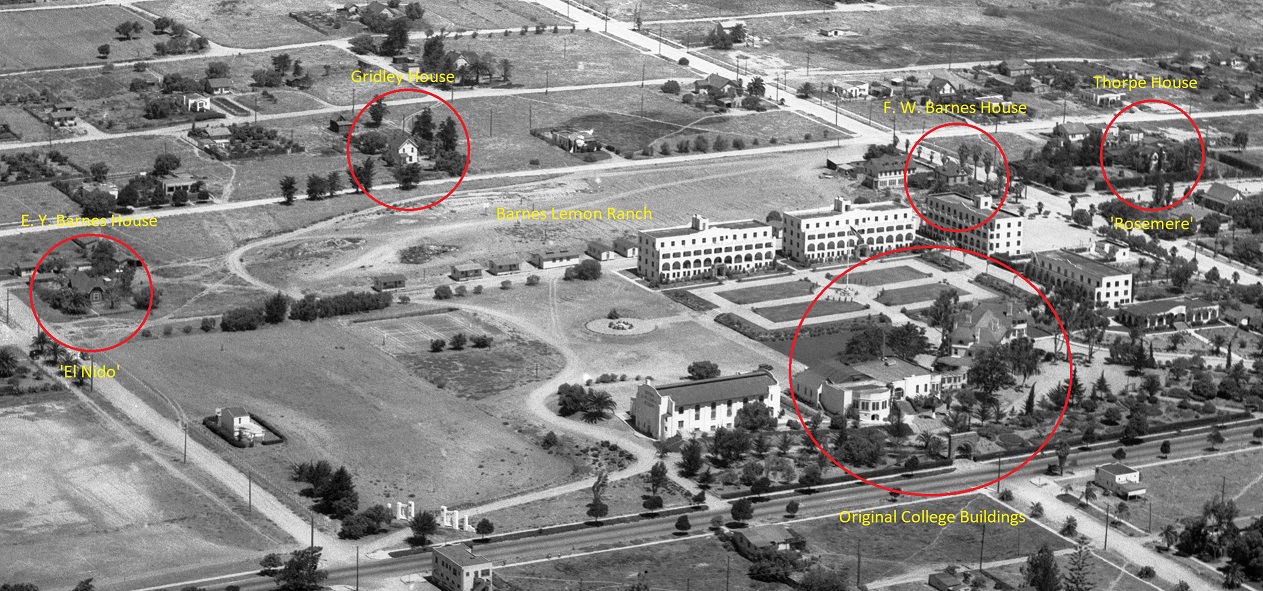

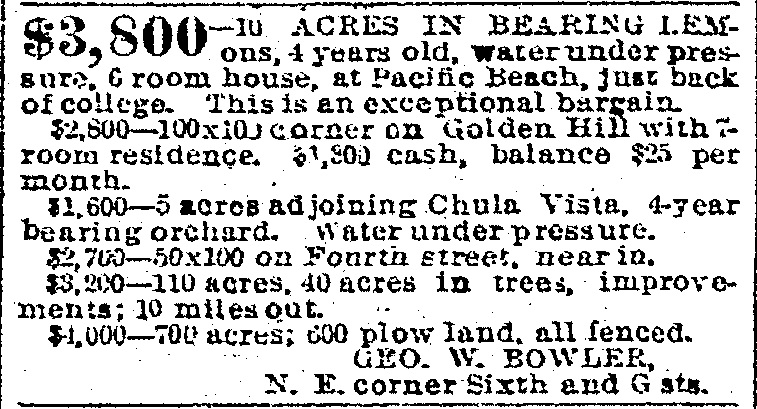

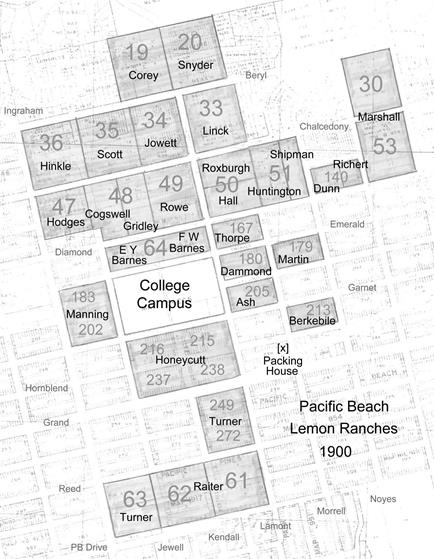

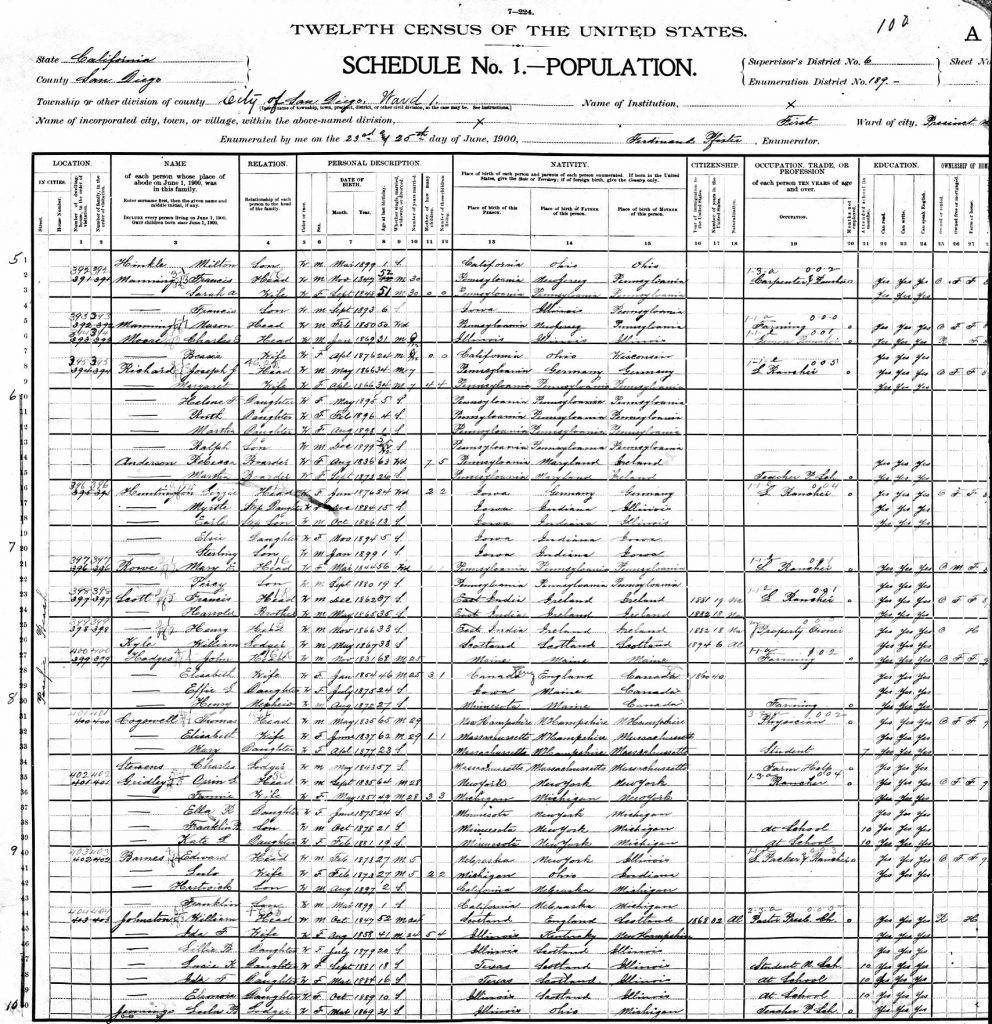

San Diego’s ‘great boom’ had collapsed in 1888 and many of the institutions it had inspired failed in the depression which followed, including the San Diego College of Letters. When the college closed in 1891 many of those it had attracted to Pacific Beach moved away and the few that remained turned to agriculture, especially lemon ranching, for their livelihoods. F. W. Barnes was among those who had come to Pacific Beach so his son Edward (E. Y.) could attend the college. He had bought lots and had a house built at the northwest corner of what are now Lamont and Emerald streets, across Emerald from the college campus. In 1892, after the college closed, Mr. Barnes purchased additional acreage around the home and he and E. Y. developed it into one of the first and most successful lemon ranches in Pacific Beach. The Thorpes also chose to remain in Pacific Beach, following the Barnes family’s example by purchasing the block on the east side of Lamont between Emerald and Diamond streets, across Lamont from the Barnes ranch, where Mr. Thorpe set out lemons and other fruit and built a house which was named Rosemere in honor of Mrs. Thorpe. The Thorpes’ orchard flourished; in 1894 he reported in the San Diego Union that the area was well adapted to fruit growing, that lemons did nicely and that he had raised a fine crop of oranges. He also noted, prophetically, that the area was unsurpassed as a favored locality for homes.

In May 1894 the railroad from San Diego to Pacific Beach was extended to La Jolla, providing access to what soon became another favored locality for homes. The Lot Books, San Diego’s tax rolls, showed that 15 ‘improvements’ were made on lots in La Jolla during 1894, more than doubling the number of dwellings present there at the beginning of the year. Some of these improvements were apparently the work of E. C. Thorpe; the Union reported in November 1894 that he had contracted to build ‘two or three cottages’ at La Jolla. One of the cottages built in La Jolla in 1894 is still standing, although it has been moved to the back of its original lot and now fronts on the alley called Drury Lane. It is not known for certain whether Mr. Thorpe was involved in its construction but the home, built for Mrs. Mudgett and named Villa Waldo, is similar in design to Rosemere, the home he built for his own family in Pacific Beach. In April 1895 the news was that Mr. Thorpe had contracted to build several more cottages in La Jolla and had taken with him every available carpenter to speed the work along. He frequently worked with John H. Kennedy, a carpenter who was also one of La Jolla’s first residents. Mr. Kennedy’s obituary in the San Diego Evening Tribune after his death in 1911 noted that he had been in partnership for many years with E. C. Thorpe and that they built ‘all of the older houses on Prospect Street’.

While most of Mr. Thorpe’s work was in La Jolla, he and his family (and the Barnes family) still lived in Pacific Beach, and the Union wrote in May 1895 that Thorpe and Kennedy, contractors with several cottages under construction in La Jolla, would bring a part of their force of men to Pacific Beach to work on the ‘Barnes cottage’. The reason became clear when in July the paper reported the wedding of Miss Lulo Thorpe and Mr. Edward Y. Barnes at the home of the bride’s parents, after which they were escorted to their new home, recently built by the groom (and Thorpe and Kennedy’s force of men) a block from the homes of both parents. Mr. and Mrs. E. Y. Barnes’ new home, El Nido, was at the southwest corner of F. W. Barnes’ lemon ranch, the corner of Emerald and Jewell streets, and F. W. Barnes soon transferred the west half of the ranch to his son.

Over the next few years Thorpe and Kennedy continued to build homes in both La Jolla and Pacific Beach. One house they built in 1896 was for a Pacific Beach neighbor, Mrs. Gridley, across Diamond Street from the Barnes ranch and about a block from the Thorpes’ own home. To save time Mr. Kennedy stayed with the Thorpes in Pacific Beach; Mrs. Thorpe wrote in her diary (January 14, 1896) that ‘Mr. Kennedy is with us and I am left rather busy cooking for my two carpenters. They commenced the Gridley house yesterday.’ Her diary entry for March 11 noted that the Gridley house was finished and on March 15 the Union reported that Mrs. Gridley was moving in (the Gridley house was at 1790 Diamond Street, next door to the house where I grew up; it was torn down and replaced by an apartment building in 1968).

The Thorpes spent much of the rest of 1896 on an extended trip to visit friends and relatives and their former homes in and around Michigan, holding entertainments there and at stops along the way to help with the costs. They left San Diego on May 1 for Los Angeles, Oakland, Salt Lake City, Colorado Springs and Denver, stopped in Nebraska to visit the Barnes family’s hometown and relatives, then continued to Chicago and finally Grand Rapids, Michigan, where they had once lived. Mrs. Thorpe’s diary confided that they enjoyed meeting family and friends and seeing familiar places but didn’t appreciate the weather and longed to be back in Pacific Beach. She also complained that while their recitals were well attended with delightful and enthusiastic audiences, they were generally not a financial success. After more recitals in small towns around Michigan they visited their former homes at Litchfield and San Antonio then returned home to Pacific Beach in October.

Also in 1896, wealthy newspaper executive Ellen Browning Scripps began her long association with La Jolla by purchasing a pair of lots on Prospect Street and in 1897 she had a monumental home built there (named South Molton Villa after the street she grew up on in London). La Jolla historian Howard F. Randolf wrote in La Jolla Year by Year that the builders were Thorpe and Kennedy, that Ed Barnes began hauling rock for the ‘Scripps cottage’ in February and that the roof was finished in April. The San Diego Union reported in October 1897 that E. C. Thorpe was at home again in Pacific Beach, having finished his contracts in La Jolla, the Scripps house being one of them. Miss Scripps and other members of her family went on to fund and support many of La Jolla’s enduring institutions, including the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Scripps Hospital. South Molton Villa burned down in 1915 and was replaced by an even grander structure designed by Irving Gill which is now the Museum of Contemporary Art.

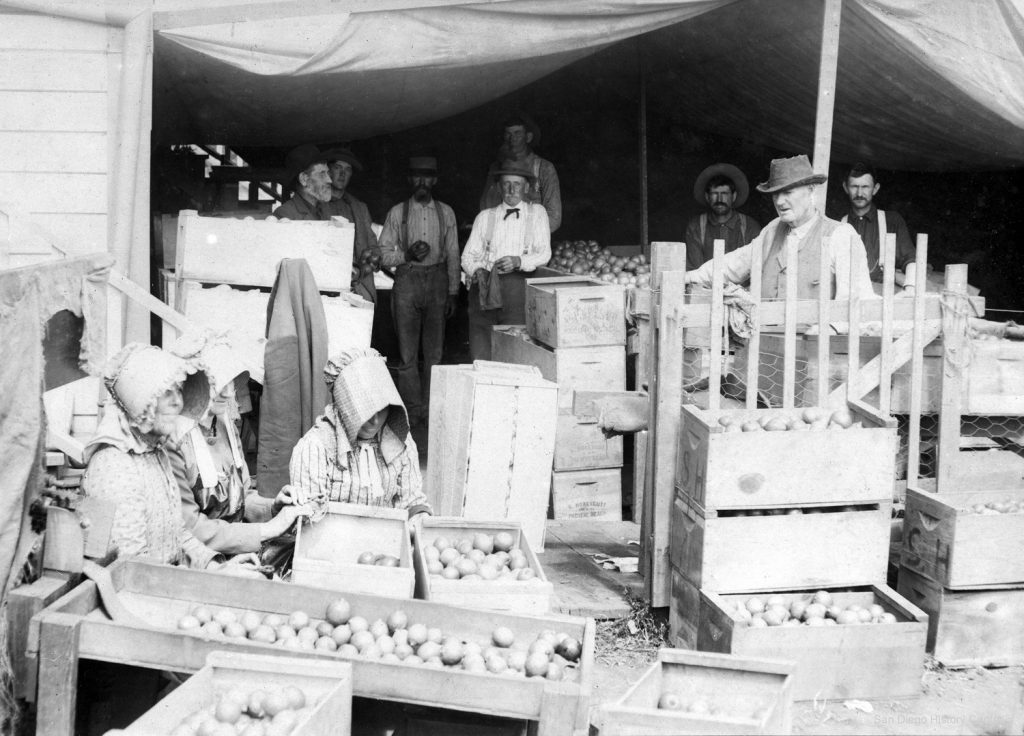

In October 1898 the County Horticultural Society met in one of the former college buildings in Pacific Beach, a block of two away from the Barnes and Thorpe lemon ranches (the stage was ‘very prettily decorated’ with ‘festoons of lemons’). F. W. Barnes told the members that he had planted 300 lemon trees five years previously and was now making over $1000 a year. He was also elected president of the society for the upcoming year. E. C. Thorpe gave a German dialect recitation entitled ‘The Huckleberry Picnic’ which was ‘exceedingly humorous and brought down the house’.

Back in La Jolla, the San Diego Evening Tribune reported in December 1898 that Mrs. Pebbles of Chicago contemplated building at an early date and that Messrs. Thorpe and Kennedy, contractors, had the plan and specification in preparation. Mrs. Pebbles’ home was at the southeast corner of Girard and Wall streets, and Howard Randolf’s book also credited Thorpe and Kennedy with building La Jolla’s first library in 1898, the ‘Reading Room’ at the northeast corner of Girard and Wall streets, across Wall Street from Mrs. Pebbles.

In August 1899 the building committee of the San Diego Board of Education was authorized to make a ‘change in the quarters’ of the La Jolla school. The Union reported that ‘the present quarters are in an old building, upstairs, with a rickety stairway leading to the room’ and were unsuitable in every way (the old building was the vacant Heald store at the northeast corner of Herschel and Wall streets). Thorpe & Kennedy proposed to erect a new building suitable for school purposes and rent it to the board. A few days later the paper reported that La Jollans were rejoicing in the erection of a new schoolhouse being put up by Messrs. Thorpe and Kennedy on a recently-purchased lot in the postoffice block. When schools opened on September 4 the thirteen pupils in seven grades and Miss Brown, their teacher, were still in their old quarters but on September 17 the new school, just completed by Messrs. Thorpe & Kennedy, was ready for occupancy and ‘would become the children’s tomorrow’. The new school was kitty-corner from the old one; on the west side of Herschel and just south of Wall Street, behind Mrs. Pebbles’ house.

Thorpe & Kennedy continued to build; in November 1899 they were putting up a home for Mr. and Mrs. Albright ‘midway between La Jolla and Pacific Beach’ according to the Union. Mr. Albright had recently purchased twenty acres there and was starting a chicken and poultry farm (the Allbrights’ twenty acres were actually within the Pacific Beach subdivision but were far from the more populated section around the former college). In 1903 the property was purchased by F. T. Scripps and subdivided as Ocean Front, four residential blocks centered on Bayard and Missouri streets).

The Albright home was ‘nearly finished’ in late November when Mr. and Mrs. Thorpe left for Riverside and ‘other interior points’ where they had engagements to give readings and recitations. They returned after a ‘very successful tour having given several entertainments’ and Mr. Thorpe went back to work; the Union reported in December 1899 that contractors Thorpe & Kennedy had ‘plenty of work at present and more a coming’. The misses Gilbert, daughters of Mrs. Agusta Gilbert of San Diego, had let the contract for a summer cottage to E. C. Thorpe and by April 1900 work was well under way. The summer cottage occupied a ‘view-commanding site above the caves’ (on Cave Street, now the Coast Walk Trail, next to where the cave store now stands). In June 1900 Thorpe and Kennedy had a new cottage house underway for Mr. and Mrs. Hawley, who already have one of the resort’s most attractive houses, as well as another for Mrs. Hebbard. In July contractor and builder E. C. Thorpe of Pacific Beach completed Mrs. Hebbard’s seaside cottage (on the east side of Herschel between Prospect and Wall streets) and had contracts for three other cottages. In August Messrs. Thorpe and Kennedy were at work enlarging the school building for the school year.

While most of E. C. Thorpe’s contracting business was in La Jolla he was still a prominent resident of Pacific Beach, where he was in charge of voter registration and served as an election judge in the November 1900 election. His neighbors, the Barnes family, were even more involved in the election; the polling place was the F. W. Barnes & Son lemon-packing house in Pacific Beach, Ed Barnes was inspector and F. W. Barnes was a candidate for the 79th District in the State Assembly, representing the city of San Diego in Sacramento. Mr. Barnes was already serving on San Diego’s Board of Delegates, having been elected from the First Ward in 1897 and again in 1899, when he was also elected President of the board. When he won the assembly seat in the 1900 election Mr. Barnes resigned from the presidency and his seat on the Board of Delegates and the board appointed E. C. Thorpe to succeed him (residents of the First Ward had petitioned to have E. C. Thorpe appointed in F. W. Barnes’ place). The minutes of the Board of Delegates record that ‘E. C. Thorpe being present duly qualifies by taking the oath of office provided by law and takes his seat in the Board’. He was appointed to the Standing Committees on Streets, Highways and Parks, on Harbors and Wharves, and also a member of the Special Water Committee. Mr. Thorpe ran for Delegate from the First Ward in 1901 and was elected with the second highest number of votes (197 out of a total of 566 votes cast; two delegates were elected from each ward). In 1901 the First Ward was still all of San Diego north and west of the bay and Upas Street. Mr. Thorpe did not run again in the 1903 election.

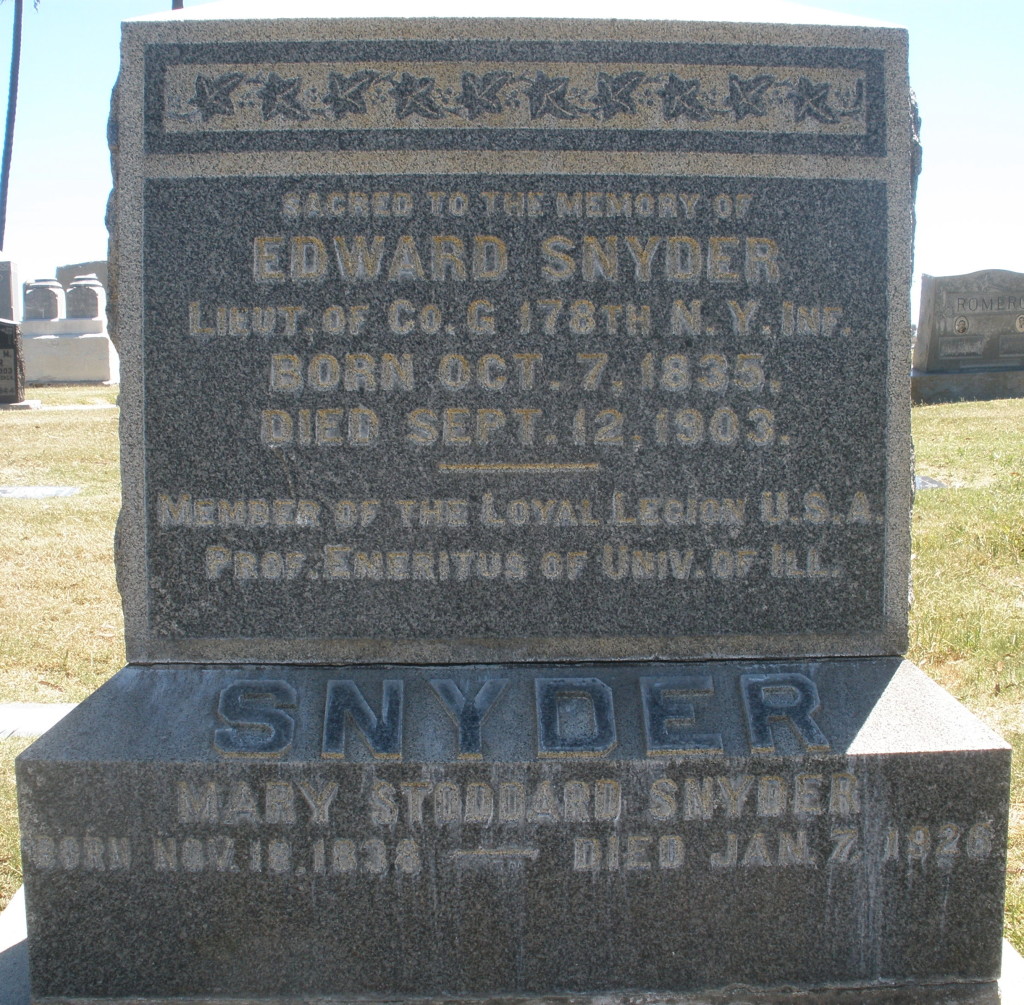

The Board of Delegates only met every week or two in the evening and Delegate Thorpe was able to continue his building activities in La Jolla, where in December 1900 he completed what the San Diego Union called a ‘very unique cottage’ for the Snyders. Edward and Mary Snyder were neighbors of the Thorpes in Pacific Beach and Mrs. Snyder was a botanist who specialized in marine algae, which flourished along the coastline of La Jolla. The cottage Mr. Thorpe built for them was on Prospect Street, overlooking the rocky shore where Mrs. Snyder spent much of her time collecting seaweed specimens during low tides (the cottage was named Corallina, after a genus of marine algae). The paper reported that the Snyders would divide their time between their Pacific Beach and La Jolla homes, but after Mr. Snyder died in 1903 Mrs. Snyder sold the Pacific Beach home and moved permanently to La Jolla.

In March 1901, contractor Thorpe began the work of finishing the church. There was money in the treasury sufficient for the inside ceiling, according to a story in the Evening Tribune, and when finished La Jollans could boast of a neat little chapel, free of debt. The neat little chapel was the Union Church, located on the west side of Girard Street across from Mrs. Pebbles’ home, a little south of Wall Street. In April 1901 the San Diego Union reported that Mr. and Mrs. Botsford visited La Jolla to note progress in the construction of the cottage E. C. Thorpe of Pacific Beach was building for them on Lincoln Street. It was built in the old colonial style and promised to be one of the most attractive seaside homes at La Jolla (Frank Terrill Botsford is considered the founder of La Jolla; he purchased the vacant land and laid out the La Jolla Park subdivision in 1887). The cottage Mr. Thorpe built for the Botsfords was intended for his nephew, F. A. Terrill, and was located next to the new school on the west side of Herschel Street (formerly known as Lincoln Avenue). In 1906 the house, known as Botsfordhurst, became the home of the La Jolla Social Club.

The Evening Tribune reported in October 1901 that Mr. and Mrs. Thorpe were stopping at Brownie No. 1 for a few days while Mr. Thorpe was doing some repairing on the Brownie cottages (there were two Brownie cottages on Coast Boulevard, near what today are the ruins of the last two La Jolla beach bungalows, the Red Rest and Red Roost; Brownie No. 2 was next door). The Tribune also broke the news that ‘Contractor Thorpe has so much business in this progressive little town that he has decided to build a cottage here. He is at present engaged with the completion of his work shop and his artistic little cottage will immediately follow’. In November the Union confirmed that the Thorpes had purchased lots on Grand Avenue and would be at home at Curfew Cottage before many weeks had passed. The cottage, which was already underway, would be finished inside in natural wood and would be both quaint and cosy. Curfew Cottage, named for Mrs. Thorpe’s poem, was on the west side of Grand Avenue (now Girard Street) north of Silverado, where the Ralph Lauren store is now. By the end of November 1901 Mr. and Mrs. Thorpe were in Curfew Cottage, completed with the exception of a little inside finishing. Ownership of their house and orchard at Pacific Beach was transferred to their daughter and son-in-law, who moved the two blocks from El Nido to Rosemere with their three children.

At home in La Jolla in January 1902 the Thorpes were guests at a very delightful evening’s entertainment given by their neighbors Mr. and Mrs. Charles Dearborn; according to the Evening Tribune Mrs. Thorpe recited her famous ‘Curfew’ by special request and Mr. Thorpe convulsed the guests with his humorous selection. In September the Union reported that the Chevailliers had bought a lot and Councilman Thorpe was building them a charming little bungalow (above the caves and today’s Coast Walk Trail). In August 1903 the news was that Mr. Burbeck’s bungalow on the bluff at La Jolla was being roofed. It was in the style of the beach house and E.C. Thorpe was doing the work (on Prospect where the HaagenDazs ice cream shop is now).

Also in 1903 E. C. Thorpe and Assemblyman Barnes made news when they purchased automobiles in Los Angeles and rode down to San Diego in their machines in exceptionally good time and without mishap. Under the headline ‘Automobiles Becoming Numerous in San Diego’ the Union wrote that ‘Nearly every day adds a new automobile to the already good-sized list in San Diego. The number now owned here by citizens is nineteen’. The most popular makes were Cadillacs, of which there were four, including the two purchased by Barnes and Thorpe; ‘The Cadillac is able to make almost any road or hill with perfect ease, and can attain a speed of forty miles an hour’. To test this claim the two men ‘raced’ their Cadillacs on the sand at low tide in Pacific Beach and made the entire length of the beach in eight minutes, about thirty miles per hour (there were no improved roads to race on at that time).

With the added responsibilities of a state assemblyman, F. W. Barnes had dissolved the F. W. Barnes & Son lemon business and sold the lemon packing plant in Pacific Beach. His son E. Y. Barnes also withdrew from the lemon business and went into the grocery trade, selling his half of the Barnes lemon ranch and taking over the community’s store, at the corner of Grand Avenue and Lamont Street. The news in January 1904 was that E. Y. Barnes was having his store very much enlarged and that Thorpe and Kennedy of La Jolla were doing the work. In September 1904 Contractor Thorpe was putting up an addition to the La Jolla school house, which would be in readiness for the opening of the fall term. In September 1905 the foundation was laid for Mr. and Mrs. Thorpe’s new residence at the northwest corner of Silverado and Herschel streets in La Jolla. Apparently this residence was completed and the Thorpes had moved there by the end of the year since in the San Diego Union’s annual New Year’s Day survey of suburban communities for 1906 ‘perhaps the most pretentious’ new residence in La Jolla was Curfew Cottage, the fine semi-Spanish villa of Mr. and Mrs. E. C. Thorpe (they had also apparently transferred the name from their first La Jolla cottage on Girard Street, which they then sold in December 1906).

An amendment to San Diego’s city charter approved in 1904 and effective in 1905 consolidated the Board of Delegates and Board of Aldermen into a Common Council, with one councilman elected from each ward. E. C. Thorpe ran for the office of councilman for the First Ward in the April election and won, taking office on May 1, 1905. One of his accomplishments as a councilman was to have funds for a La Jolla sewer system included in a civic improvement bond issue approved by voters in 1907. The marine biology station recently established at La Jolla required clean ocean water and was hesitating to expand there unless something was done about increasing pollution. With funding for a sewage system assured and with the financial support of Miss Scripps and her brother E. W. Scripps the biological station did expand into what eventually became the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

In November 1905, the Evening Tribune reported that E. C. Thorpe was planning to withdraw from the contracting business and confine himself to the supervision of building operations. Mr. Thorpe did not withdraw from his other avocations, however. In April 1906 there was a reception for the departing Rev. Pearson at the Union church at which Rose Hartwick Thorpe recited ‘Curfew’ and Mr. Thorpe rendered some of his comic Dutch recitations. They were enthusiastically received.

In 1907 the Thorpes moved again, this time from La Jolla to the uptown area of San Diego. According to the Union in March 1907, Councilman E. C. Thorpe had purchased lots in Brooke’s addition, on Third Street between Pennsylvania and Robinson Avenues and would begin construction of a fine home within a short time. Their new home at 3737 Third was a few blocks north of Upas Street, still within the First Ward, and Mr. Thorpe ran for the city council again in 1907 but was defeated. He also apparently reconsidered his plan to withdraw from the contracting business; in August 1907 the Union reported that construction on the new high school at Ninth Street and C Avenue in National City was proceeding at a rapid rate and it would be completed by September 8. The contract was let to E. C. Thorpe and amounted to more than $20,000; ‘the building, which is of brick with plaster exterior, is one of the prettiest little buildings of its kind in the state’.

Mr. Thorpe had formed a partnership with Edgar Shockley in 1906 and in November 1907 the papers reported that E. C. Thorpe of the firm Thorpe & Schockley was the only bidder for the alteration work on the fire engine house No. 2 at Tenth and B streets. The contract was for $780 and the alterations would include the installation of earth foundations in the horses’ stalls in place of cement ones and to widen the entrance to give room for three horses abreast as the new engine there was to be driven by three horses instead of two.

In March 1908 contractors E. C. Thorpe and F. B. Shockley entered into a $18,444 contract to build a residence for Melville Klauber at the corner of Redwood Street and Park Avenue (now Sixth Avenue), across from City (now Balboa) Park. The Klauber house was designed by Irving Gill and was considered one of his most significant works. Mr. Klauber was a manager at the family-owned Klauber-Wangenheim wholesale grocery, tobacco and liquor business; he was the oldest son of founder Abraham Klauber, was married to the daughter of his father’s partner, Julius Wangenheim and he became president of the company when Abraham Klauber died in 1911. The Klauber house was demolished in 1979 after a hard-fought battle by San Diego’s Save Our Heritage Organization to preserve it, and the site was left vacant for another ten years before a 10-story condo tower was erected there.

Thorpe & Schockley were also contracted to build four arches and a reviewing stand along the route of a planned parade from the bay to City Park to celebrate the arrival of the Great White Fleet in April 1908. The arches were also designed by Irving Gill and were to be covered with flags, flowers, ferns and bunting for ‘daytime show’ and electric lights for night-time. Thorpe & Schockley also built booths in the plaza and on Santa Fe wharf where the young women of San Diego would serve sailors with fruits and flowers. The Great White Fleet consisted of sixteen white-painted battleships which, along with auxiliaries and escorts, were on a round-the-world cruise to demonstrate the power of the United States Navy. After leaving Hampton Roads, Virginia, in December 1907 the fleet sailed around South America and anchored off Coronado on April 13, 1908 (the bay was then too shallow for battleships). Huge crowds were on hand to welcome the sailors when they were brought ashore and paraded through the streets on their first United States port call. The ships departed a few days later for San Francisco and other west coast ports before continuing across the Pacific Ocean to Asia, around Africa to Europe, and across the Atlantic back to America in February 1909.

In the early 1900s one of San Diego’s most prominent social organizations was the Cabrillo Club. It had begun in 1893 as San Diego Wheelmen, a group formed to promote the use of the newly introduced ‘safety’ bicycle but which by 1900 had become more of a social club and forum for the discussion of civic issues. It became the Cabrillo Club in 1903 and in 1915 its name was changed again to the Cabrillo Commercial Club. E. C. Thorpe became ‘one of the foremost members’ and was elected a director in 1908, also serving a term as vice-president in 1909. The club had been his hobby since he retired from active business and he was ‘one of a group of elderly men whose counsel carried much weight in the civic and commercial problems that were considered by the organization’ according to the San Diego Union.

The Thorpes moved again, in 1911, to a site in Mission Hills overlooking what were once the tidelands of San Diego Bay and with a fine view of the bay and Point Loma. The house, at 1981 Linwood Street, is still there and the view now includes the Marine Corps Recruit Depot and San Diego Airport, opened in the 1920s after the tidelands were filled in. E. C. Thorpe did not witness these developments, however; in November 1916 he was walking on a downtown street after lunch at the Cabrillo Club when he was stricken with ‘acute heart trouble’ and died while being taken to hospital. The Union’s obituary noted that Edmund C. Thorpe had been a prominent figure in San Diego for 30 years and had been in the business of building contracting, was at one time a member of the City Council and had been a director of the Cabrillo Commercial Club for several years. The Union added that he was ‘also known and liked in the literary circles of which Mrs. Thorpe, by virtue of her writings, was a part’. He was survived by his wife, Rose Hartwick Thorpe, the author of that world famous poem, ‘Curfew Must Not Ring Tonight’, a daughter and a brother. He was also survived, for a time at least, by the bungalows, cottages, mansions and schools built by Mr. Thorpe and his partners, particularly in La Jolla.