In July 1904 the San Diego Evening Tribune reported that after five days’ careful consideration of over 1,200 names submitted for their new hotel at Pacific Beach, Folsom Bros. Co. wished to announce that the name finally selected was Hotel Balboa. Ten different contestants had suggested the name and Folsom Bros. awarded the prize, choice of a $100 lot in Pacific Beach or $100 in gold, to the first; the other nine would be eligible for a $20 discount on any lot they may select from the company’s holdings. Folsom Bros. Co. had received letters from all over the United States and even from Canada and considered the name a happy choice as the discoverer of the mighty western sea would always be associated with the Pacific Coast. That a splendid hostelry, where the weary traveler may find rest and recuperation, should be built upon the shores of the sea which he discovered and should bear his name seemed both timely and appropriate.

The splendid hostelry to be named after the discoverer of the Pacific Ocean was not actually new. The original building had been built in 1888 for the San Diego College of Letters on its campus north of what is now Garnet Avenue and west of Lamont Street. It was the first substantial structure in Pacific Beach, designed and built by James W. Reid, architect of the Hotel del Coronado. A second college building was added in January 1890, just west of the original building and across Garnet from Kendall Street. That building was funded by O. J. Stough, owner of most of Pacific Beach at the time, and became known as Stough Hall. The college failed in 1891 and the college campus property was the subject of several foreclosure auctions at the courthouse door before being acquired by William Johnston, minister of the Pacific Beach Presbyterian Church, with the intention of reestablishing a college at the site. However, the college project never materialized and instead Rev. Johnston and his family moved into the main building and also rented rooms to boarders and visitors, especially easterners visiting during the winter season. By 1901 it was listed in the San Diego city directory as the College Inn, with Rev. Johnston as secretary and manager. Stough Hall became the venue for dances and other community activities for Pacific Beach residents.

Folsom Bros. Co. was a real estate company that controlled the Fortuna Park additions south of Pacific Beach and in 1903 purchased O. J. Stough’s holdings, giving it control of the majority of the property in Pacific Beach as well. To stimulate lot sales Folsom Bros. began a program of improvement and development, grading streets and adding curbs and sidewalks in what was then the center of the community, the area around Hornblend and Kendall streets south of the college campus. In April 1904 the company also leased the campus itself, the four blocks surrounded by Garnet Avenue and Jewell, Emerald and Lamont streets which included the College Inn and Stough Hall. In addition to $50 per month rent Folsom Bros. would be required to spend a like amount in improving and repairing the grounds and buildings – painting the inn was particularly mentioned. The terms included an option to continue the lease for a second year at $100 per month or to purchase the property for $15,000. Folsom Bros. announced that the property would be developed into a first class resort.

After deciding on the appropriate name in July, Folsom Bros. began the conversion of the former college into the promised first class resort. The company announced in September 1904 that a subsidiary, the Pacific Beach Construction Company, would be incorporated to undertake the development and complete the Hotel Balboa. The work was still underway in April 1905 when Folsom Bros. Co. exercised its option to purchase the college campus from Rev. Johnston. In August 1905, the San Diego Union announced that the new Hotel Balboa would be thrown open to the traveler and tourist, although the regular formal opening would take place later, at the beginning of the winter season. Travelers and tourists responded; the weekly Pacific Beach news column listed guests from Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Arizona and Texas during October and November. In mid-November, artistically printed folders and cards distributed throughout the city announced that the new Hotel Balboa was offering the general and traveling public a low special rate for a few weeks until the formal winter opening, affording an unusual opportunity to enjoy a period of sea and bay side life at this favorite Southern California resort at greatly reduced rates.

The Union’s annual New Year’s Day review of San Diego’s communities in 1906 proclaimed the opening of the magnificent Hotel Balboa in the very heart of Pacific Beach to be of first importance among the large number of improvements that had taken place in that suburb during the year 1905. In point of architectural beauty, location and appointment it stood second to none in San Diego. The grounds were in process of being adorned and beautified by flower gardens, stately walks and drives and it had been furnished throughout in admirable style and was capable of accommodating over 100 guests. It was situated on an eminence over 100 feet above sea level giving a magnificent view of every aspect of scenery that this favored spot afforded. A feature that the guests found especially interesting was the observatory erected over the building which contained the dining room and ballroom, which brought the whole country in the environs plainly into view (the dining room and ballroom were in Stough Hall; the ‘observatory’ was the tower Rev. Johnston had built over Stough Hall in 1898). To the south lay Mission Bay, one of the finest bodies of still water in California, four miles long and two miles wide with exceptional opportunity for indulgence in still water sports. The bathing and boating was ideal and during duck season its surface was covered with all sorts of birds. The hotel’s cuisine was un-excelled and its rates reasonable, ranging from two dollars a day upward. Every room had an outside exposure and was provided with city water, electric lights and telephones. The new and elegant furnishings and excellent service made it a delightful spot in which to rest or recreate.

However, the hotel’s first season was a short one. In April 1906 the last two guests, Alexander and Mary McGillivray, returned to North Dakota and the hotel closed for the summer to allow improvements that would greatly add to its list of attractions (the McGillivrays were winter visitors who owned a 20-acre ranch four blocks south of the hotel that never had a ranch house of its own). Larger palms in the ballroom and ping-pong room and several exterior cozy corners were among the latest features. Additional work on the ballroom floor made it so tempting that impromptu dances had been held nearly every night since its completion. Although the hotel itself was closed, many people, both residents and tourists, spent a day or more at Pacific Beach and the Hotel Balboa. Most of them came out of curiosity, having heard what an excellent place it is for a day’s rest or outing. Garnet Avenue had been graded and surfaced with oil and driving over the fine oiled boulevard delighted many of the visitors. Young people found great enjoyment swimming, boating and playing on the hotel tennis courts. It not being in the nature of young people to sit still, the evenings usually ended on that slippery floor in dancing.

That ballroom was the scene of a ‘floral contest’ in June 1906, a ‘fairyland of color and costume’. The San Diego Union reported that the ballroom never looked more beautiful and there had never been a larger or more delighted concourse of people assembled there. Almost the entire population of Pacific Beach turned out, along with visitors from La Jolla, San Diego and Los Angeles. The ping-pong room, converted into a reception hall, was canopied with huge pepper boughs. In the large bay-window alcove of the ballroom cypress branches were used and their pungent fragrance filled the entire building. The ballroom itself was one great bower of palms. Miss Lena Campbell won the prize for the most artistic floral costume, a white princess gown covered with asparagus fern and white carnations. One woman appeared in the unique but somewhat startling costume of Mother Eve, modernized by a black dress under the fig leaves. There were many in white with ropes, wreaths and solid banks of roses, lilies, honeysuckle and other flowers.

Hotel Balboa had been conceived as a year-round resort, and in June 1906 Folsom Bros. Co. published a letter in the Union addressed ‘to the pleasure seeker’; with the approaching of summer the one thought which comes to all is ‘Where shall we spend our vacation?’. The letter suggested that in forming a decision the main points to be taken into consideration should be the opportunities for a complete rest and change, the number of pastimes and pleasures to be enjoyed and lastly the expense. The Hotel Balboa was the most delightful year round resort hotel on the coast; the beautiful parlors, wide verandas, large airy comfortably furnished sleeping apartments, cozy, light dining rooms and the very best cuisine, a large ballroom with splendid floor for dancing, and out of door sports, such as tennis on new double tennis courts, croquet, boating and bathing on Mission Bay, pleasures on the beautiful beach, driving, shooting and rambling in the foothills were but a few of the delightful amusements. There were special weekly and monthly rates for the summer season. The hotel’s amenities and amusements were also described in a beautifully illustrated brochure.

Pacific Beach celebrated the Fourth of July in 1906 with picnic lunches at the beach, games and sports, songs, addresses, a concert by the city guard band and fireworks. Although these activities would take place at the beach, the day would begin and end at the Hotel Balboa. All carriages, automobiles, bicycles, etc., would assemble at the hotel at 8:30 a. m. to march to the water front and after the fireworks display in the evening from the cliff at Diamond Street would return for dancing at Hotel Balboa. The Evening Tribune reported that the program was carried out smoothly from the beginning of the parade until the last dance at midnight.

Activities at the Hotel Balboa increased as the summer season advanced in 1906 but the San Diego Union noted that formal affairs did not find as much favor as impromptu musicales, card parties and dances. Outdoor activities were also popular; from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. all who could be coaxed off the veranda and shaded lawns spent that time in and on the bay, and many enthusiastic fishermen sought the surf every evening. Everyone drives, as the afternoon cools, or else plays tennis or croquet. The young people of Pacific Beach had begun practicing tennis and hoped before long to announce a tournament. After dinner, cards and games were brought out and at the hotel few evenings pass without a visit to the ballroom by the devotees of the dance. For the card games in the parlors of the Hotel Balboa, dignified games like whist were put aside for more frolicsome games of hearts or black-jack. Parties from the hotel also went boating at night to see the ‘phosphorus’, the glassy surface of Mission Bay lighting up wonderfully with the movement of the boat and touch of the oars.

Improvements continued in 1907; Folsom Bros. ads for Pacific Beach real estate noted that the grounds of the Hotel Balboa were being laid out and developed at great expense by the eminent landscape architect responsible for the beautiful Westlake, Eastlake, Elysian, Echo and Hollenbeck parks in Los Angeles. In February a building permit was issued for a pergola connecting the two buildings of the Hotel Balboa, valued at $1000. The Union reported in July that for six months men and teams had been digging, cutting, filling and leveling on the grounds of the Hotel Balboa. The grounds had been laid out on the front and rear and on the west side of the hotel in curb drives and walks, spaces for grass plots and squares for cottages. No planting had been done as yet and would not be until winter rains came but looking at the grounds from the tower over the ballroom of the hotel one could see the lines and curves and could not but realize that the hand of an artist had been at work.

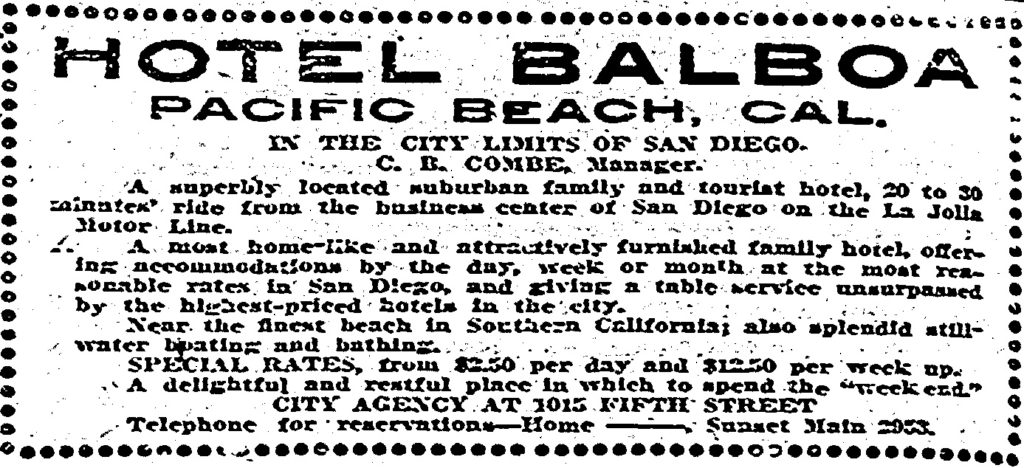

The 1907 makeover of the hotel also involved a change in management and a different approach to the visitor experience. Folsom Bros. had marketed the hotel as a first-class resort, a place for out-of-town visitors to spend a vacation, but in the summer of 1907 ads described Hotel Balboa as a most home-like family hotel, a delightful and restful place in which to spend the ‘week end’. Although the new decorations, furnishings and alterations that had been in progress for several months were not entirely completed, the new management decided to throw open the hotel for its first ’week end’ in July and as a result the house was filled to overflowing with a very select party of San Diego business and professional men and their wives and families. Some came Saturday morning but most arrived on the 3:30 train, prepared to stay until Sunday evening. An eight-course dinner was served at 6 o’clock in the new dining room and then the new ballroom was thrown open and a well-known orchestra called young and old to the dance, which lasted until midnight.

By August 1907 the Union was reporting that the ‘week ends’ recently inaugurated by the new management of Hotel Balboa were proving a great success and seemed to fill a want long felt by those of San Diego’s business and professional men who, with their families, liked to get away from home and business surroundings for a quiet Sunday of rest and recreation. Ever since the recent remodeling and refitting of the hotel the idea of spending weekends at Hotel Balboa had been growing in favor, and now every Saturday afternoon the train dropped an increasing number of people at Pacific Beach to enjoy the outing so that the number of ‘week enders’ together with the regular guests of the hotel filled the house to overflowing. Interestingly, many of the arrivals listed in reports of the hotel ‘week ends’ were Pacific Beach residents and their wives who were unlikely to have arrived on the Saturday afternoon train. Mr. and Mrs. James H. Haskins, whose home was at the corner of Diamond and Ingraham streets, and A. S. Lane, whose home on Hornblend near Kendall (now the Baldwin Academy) was within shouting distance of the hotel, probably walked. Not all the guests were local either; hotel arrivals in September included Mr. and Mrs. A. F. MacFarland, who apparently liked what they saw in the vicinity and bought lots at the corner of Beryl and Lamont where they built the neo-classical home that is still standing there.

San Diegans were again well represented at the Hotel Balboa ‘week ends’ in September, filling the popular hotel to overflowing. The vaudeville entertainment given in the ballroom proved to be the best ever, creating screams of laughter from all sides of the room. The performers (who were dressed up as crows, even to beak and claws) were called back again and again. In addition to the 50 hotel guests, 100 Pacific Beach and La Jolla residents were present. Following the performance light refreshments were served and dancing indulged in until the midnight hour. The hotel arrivals column listed the 50 guests, most of whom were residents of San Diego and again included many Pacific Beach residents including the Haskins and also V. J. Hinkle and family (who lived in the house now at Law and Ingraham streets) and Mr. and Mrs. F. T. Scripps (of the former Braemar mansion at the foot of Bayard). Mrs. Scripps’ sisters, Misses Violet and Fannie Jessop from Coronado, were also hotel guests. Out-of-town visitors in September 1907 included a group of nine ‘Hawaiian beauties’ who visited Pacific Beach, where they were met with carriages and taken by Folsom Bros. on a drive. The tour included a stop at the Hotel Balboa where they had about an hour and a half to themselves; they played pool, danced and sang many of their native songs, then were guests at a delightful tea given by Folsom Bros.

The hotel ‘week ends’ for business and professional people from San Diego came to an end in 1907 and by early 1908 the news was of the entertainment and social activities held at the hotel; old-fashioned dances and songs in the ballroom and whist in the card rooms. Manager C. B. Combe gave a sailing party on Mission Bay and members of the Pacific Beach theatrical club were rehearsing for their entertainment, to be given in the hotel theater. There would be a minstrel part, followed by vaudeville, then refreshments and dancing. In March 1908 a ‘baby party’ was one of the most enjoyable events ever given at the popular house. Every room was full and many guests had to be turned away. A number of gentlemen chose the Buster Brown costume, some appeared as Little Lord Fauntleroy and others were simply Mamma’s Pets in loose jumpers and big sashes. The ladies were so charming that it was a pity they could not dress in the sweet simple costume of a child at all times. The new tennis courts were finished, and although hotel arrivals included some parties from New Jersey, Pittsburgh, and even Nome, Alaska, most arrivals were from the local area, perhaps responding to ads emphasizing a homelike atmosphere and the lowest rates in the city; family rates were said to be lower than housekeeping.

In February 1908 W. W. Whitson, president of the Hillcrest Company, purchased an interest in Folsom Bros. Co. and was installed as its first vice-president and treasurer. In May, Mr. and Mrs. Whitson held a ball and card party at the Hotel Balboa that the society page of the Union called one of the most pretentious society events of the season. Between four and five hundred guests from San Diego took the La Jolla line train from Fourth and C streets downtown, special rates having been secured for their accommodation. On arrival at the pretty village of Pacific Beach a broad boulevard lighted by hundreds of swaying Japanese lanterns led to the brilliantly illuminated hotel, where elaborate decorations of palms, greenery and geraniums were arranged throughout the picturesque rambling structure. A list of the hundreds of guests, a virtual who’s who of San Diego society at the time, was continued on a second page (Mr. Whitson’s association with Folsom Bros. Co., and the hotel, ended in November 1908 when the Folsom brothers bought out his interest).

While the ballroom and other amenities were popular for dances and other community activities and the hotel rooms could be filled on weekends by local residents attracted by the lowest rates in town, the Hotel Balboa never became the commercial success that Folsom Bros. Co. had anticipated and by 1909 it was apparently closed; no ads had appeared since mid-1908, it was no longer listed in the ‘hotel arrivals’ columns and guests were no longer mentioned in the news reports from Pacific Beach. When a group of leading Pacific Beach citizens, including Mr. MacFarland and Mr. Haskins, formed the Pacific Beach Country Club in February 1909 a portion of the Hotel Balboa was sub-leased for their club rooms. When the country club hosted a delightful dance in May 1909 the ‘north wing of the big hostelry’ was turned over to the guests of the club, about fifty of whom were taken out from San Diego on a new gasoline motor car, which made a special round trip for the occasion (one of the new McKeen rail cars, or ‘Red Devils’, introduced to the La Jolla line in 1908).

The hotel buildings and grounds were ready for other opportunities and in November 1910 Captain Thomas A. Davis, a veteran of the Puerto Rican campaign of the Spanish American War, leased the property and opened the San Diego Army and Navy Academy on the site. Although there were only thirteen cadets in the first class and he was the only instructor, the academy thrived under Capt. Davis’ leadership and soon outgrew the original hotel buildings. After considering a move to a larger facility in the Loma Portal area Davis instead purchased the college campus property in 1921 and in 1923 added on by acquiring the two blocks on the north side of the campus and two more blocks on the west side in 1925.

The hotel buildings continued to be used for teaching and administration but the growing battalion of cadets was housed first in rows of wooden cottages and then in enormous reinforced concrete barracks built between 1928 and 1930. The cost of this building program combined with the economic downturn of the Great Depression led to the academy’s bankruptcy in 1936 but it was taken over in 1937 by the John E. Brown College Corp. and operated until 1958 as Brown Military Academy. The property was then developed into a shopping center and the old buildings, once the Hotel Balboa and originally the San Diego College of Letters, were demolished. Workers razing the buildings found a tin baking soda can containing newspapers, maps and other articles placed in the cornerstone at its dedication in 1888.

Today the only reminder of these earlier times is a small monument dedicated to Brown Military Academy outside a Chinese restaurant in the shopping center. The monument includes an aerial photo of the academy that shows the buildings that had once been the Hotel Balboa – and are now a parking lot.