An announcement in the San Diego Union on Saturday, January 28, 1888, invited citizens to attend the laying of the cornerstone of the San Diego College of Letters in Pacific Beach. Speakers at the ceremony would include the celebrated poet Joaquin Miller, the ‘Poet of the Sierras’, and a free lunch was promised. Trains would leave the downtown depot at 9 and 10 o’clock A. M. and return at 1 and 3 P.M. Fare for adults was 50 cents, children 25 cents.

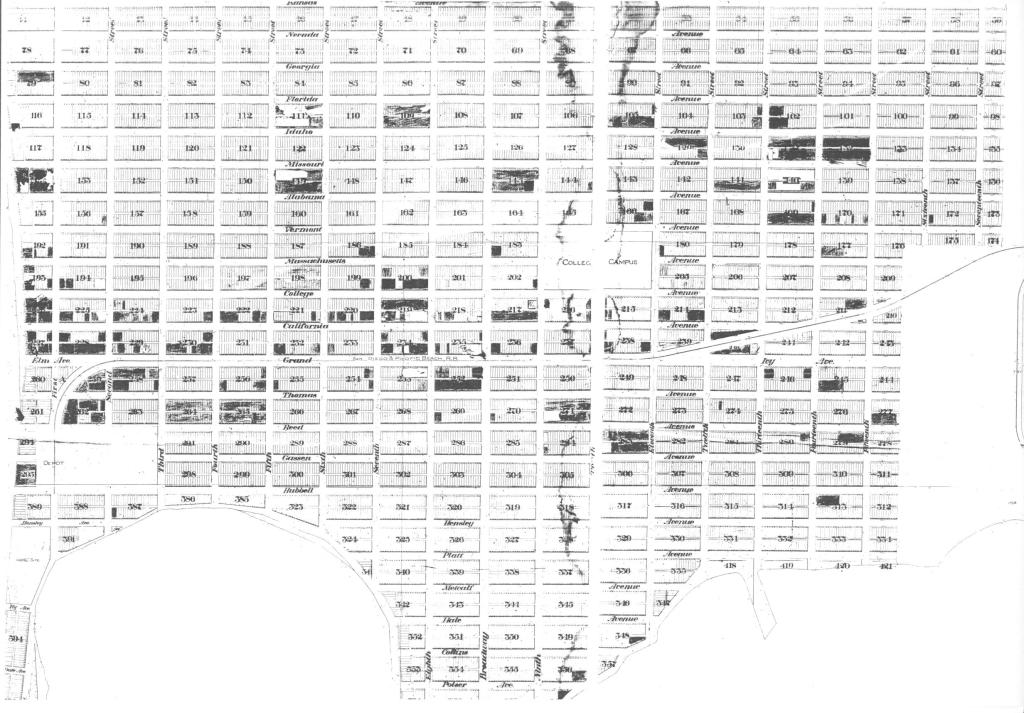

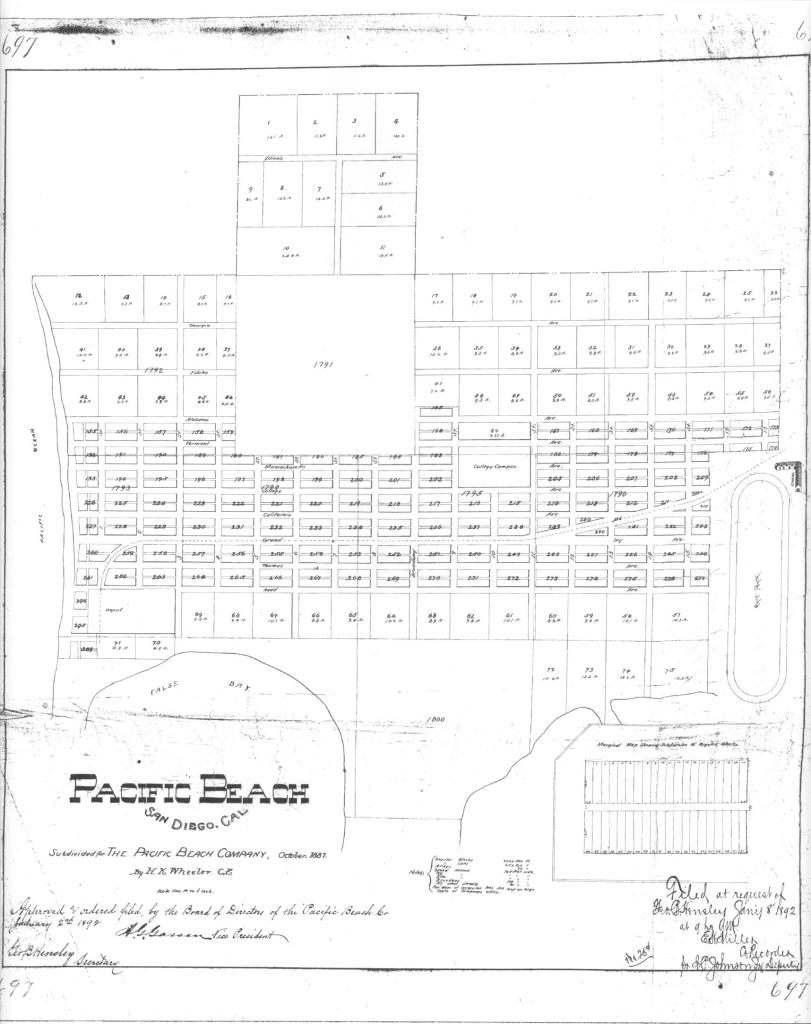

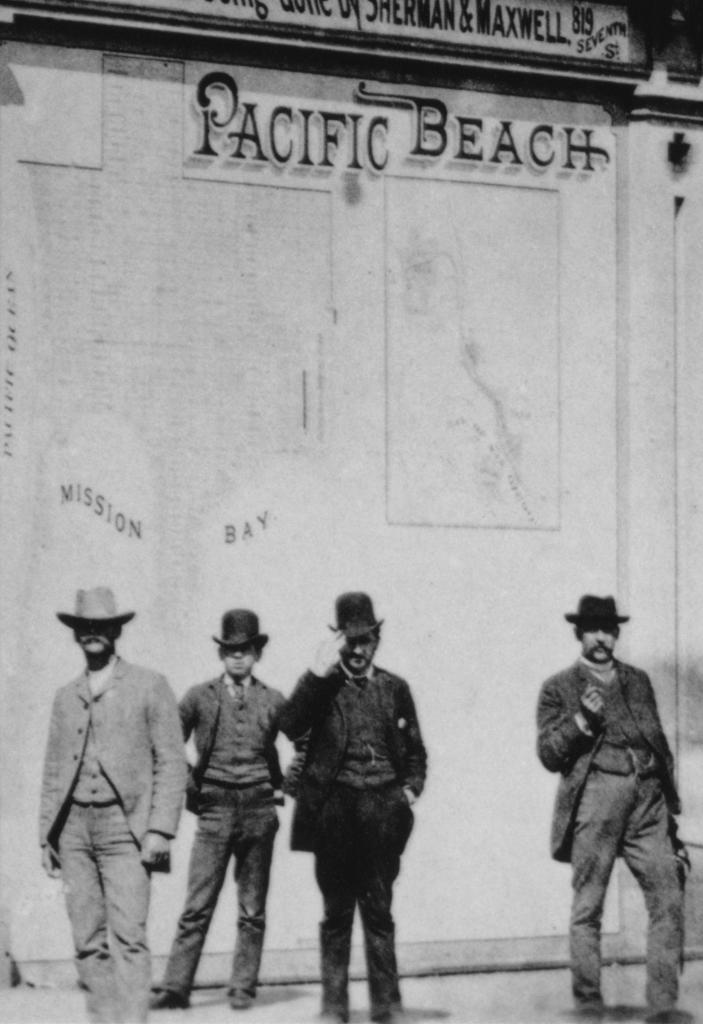

The college was intended to be the centerpiece of the new community planned for the area north of Mission Bay and east of the Pacific Ocean, and was to be built on a four-block campus now occupied by the Pacific Plaza shopping center on Garnet Avenue between Jewell and Lamont streets. At the time, Pacific Beach was almost entirely undeveloped; the Pacific Beach Company had been incorporated in July 1887, a subdivision map was drawn up in October and the opening sale of lots had been held in December 1887, just a few weeks before the cornerstone ceremony was to take place (the platform built for the ceremony may have been the largest structure around at the time). The railroad from San Diego was still under construction and passengers attending the cornerstone ceremony in January 1888 would actually have traveled over the rails of the California Southern mainline railway from downtown to Morena, where they would have switched over to a portion of the Pacific Beach line which continued from there to the vicinity of the college campus (the railway from downtown San Diego to a depot near the beach at the foot of Grand Avenue was finally completed in April 1888).

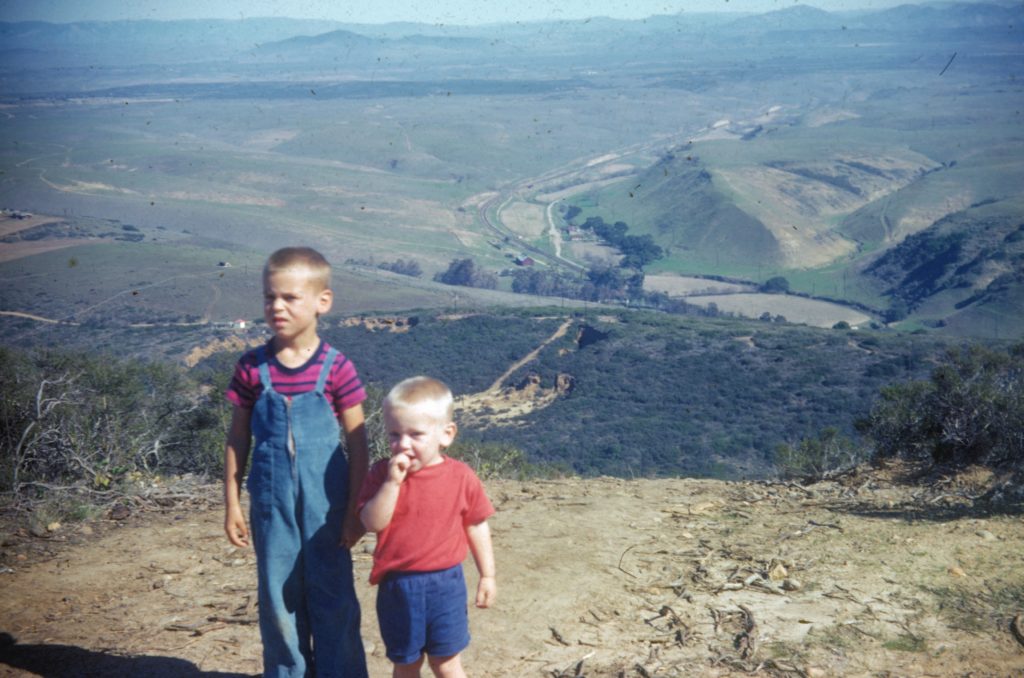

According to the Union about 2500 people traveled to Pacific Beach to witness the laying of the college cornerstone, and the green grass and the sublime scene from the college campus made the occasion a most interesting one. One of the speakers described the scene as a ‘hilltop with its slopes stretching down to the placid bay and out to the roiling sea, while in the distance, but in full view, lies the busy city and the harbor filled with ships, and beyond the majestic sweep of the mountains, some green with spring-like verdure, and others white with snow’.

When Joaquin Miller stepped to the front of the platform to read the poem he had composed for the occasion he was greeted with an ovation ‘that could not but have gratified the gifted man of verse and sentiment’. The sentiments in Mr. Miller’s verses included:

We lift this lighthouse by the sea,

The west-most sea, the west-most shore,

To guide man’s ship of destiny

When Scylla and Charybdis roar;

To teach him strength, to proudly teach

God’s grandeur, by Pacific Beach.

(Scylla and Charybdis were a pair of mythological sea monsters on opposite sides of a narrow strait, menacing seafarers forced to sail between them)

There were other orations, music by the City Guard band and an address by the president of the college company which concluded with the promise that San Diego College would become ‘a scientific and literary light-house, guiding the people of the city and the world into the golden harbor of wealth, culture, character and happiness’. The cornerstone was then loaded with copies of local newspapers, copies of the poems and addresses delivered on the occasion, coins, and a copy of the Bible. It was then lowered into place with the words ‘we lay the cornerstone of San Diego College – unsectarian but not un-Christian – her faith the faith of Christendom – her hope the hope of the civilized Christian world.’

The San Diego College of Letters was the brainchild of Harr Wagner, publisher of the Golden Era magazine which Wagner had moved from San Francisco to San Diego in 1887. He believed that San Diego was destined to become a great city and that the city was the right size to support a college, ‘not a small insignificant institute, but an institution that will compare favorably with the noted colleges of America’. In August 1887 Wagner and two other alumni of his alma mater, Wittenberg College, in Springfield, Ohio, formed the San Diego College Company ‘to erect and construct buildings to be used for colleges, universities, and in connection therewith to carry on, control and maintain colleges and universities’. Wagner’s partners in the college company were C. S. Sprecher and F. P. Davidson (who was married to Sprecher’s sister Ella). C. S. (and Ella) Sprecher’s father Samuel Sprecher had served as president of Wittenberg from 1849 to 1874 and played a major role in establishing it as a successful educational institution (Wittenberg University still exists in Springfield). Hoping to repeat this success in Pacific Beach, the partners recruited the elder Sprecher to serve as president of their new college.

The college company also came to an agreement with O. S. Hubbell, one of the founders of the Pacific Beach Company, to include the college in plans for their new town site. Accordingly, the original Pacific Beach subdivision map featured a four-block college campus near the center of the community (on College, now Garnet, Avenue). The company contracted with James W. Reid, architect of the Hotel del Coronado, to design and supervise construction of the college buildings, and following the cornerstone ceremony construction proceeded through the spring and summer of 1888.

The September/October edition of the Golden Era contained the announcement that the college would begin its educational work on September 20, 1888. It would be undenominational and would admit both sexes to all the advantages of the curriculum. One of the advantages both sexes could enjoy was the opportunity for out-door drill, summer and winter, due to the evenness of the climate. The exercise would be ‘healthful and invigorating’ and the young ladies would be allowed to form their own military company.

A Bachelor of Arts degree would be conferred on students who completed the Classical course after four years of study. Applicants for the Classical course would have to be at least 14 years of age and would be examined in Latin, Greek (or its equivalent), mathematics, history, geography, English and physiology. There would also be Scientific and Literary courses leading to comparable degrees, and for which modern languages could be substituted for Greek. Latin would be optional after the sophomore year, but students were expected to able to read the classics (in their original languages) with literary pleasure, as repositories of history and literature. Students younger than 14 or not meeting the requirements for admission could enter a Preparatory course, designed to prepare them to enter the freshman class but also to provide a course of study that was complete and practical in itself. The academic year would consist of three terms of 13 weeks each with each term’s tuition set at $16.50 for Preparatory students and $22.00 for Classical, Scientific and Literary students. Resident students would also pay $97.50 for board and room rent, and an extra fee of $10.00 was added for music, $3.00 for voice culture and elocution, and $5.00 for painting.

The San Diego College of Letters did open on September 20, 1888 with 37 students, and enrollment increased to 104 for the second term in January 1889. The Annual Catalogue for the 1888-1889 collegiate year included a list of the students’ names and home towns which showed that 23 of the 104 students were residents of Pacific Beach, 45 were from other areas of San Diego, 12 from Coronado and 10 from other parts of San Diego County. Only 8 students were from out of state, including two from Lower California. Judging by their names (Bessie, Hattie, Emma, etc.) 46 of the students were young ladies and 57 were young men (e.g., Horace, Edgar, Cyrus).

In addition to the grant of the college campus property, the Pacific Beach Company had given the college company hundreds of residential lots throughout the community as an endowment to secure its financial future. However, San Diego’s ‘Great Boom’ which had followed the completion of a transcontinental railroad link in 1885 and the influx of thousands of potential settlers collapsed in 1888, causing a sharp decline in the population and a corresponding lack of demand for residential real estate. The college attempted to generate interest in its lots by holding auctions where choice residence and villa sites would be sold to the highest bidder. Potential buyers were also treated to lunch, which could be roasted ox, ‘carved and served to the hungry throng’, or a fish fry. Three auctions were held in February and March of 1889 which drew large crowds but apparently few bidders. Instead, to relieve its immediate debt and other obligations, the college mortgaged much of its real estate. The financial outlook deteriorated further in April 1889 when James W. Reid sued the college company for what he claimed was owed for the design and supervision of construction of the college building.

Still, when the first academic year came to an end in June 1889 the mood at the college was upbeat. The final edition of the College Rambler, the student newspaper, included an editorial ‘to you fellow students whose years work is so nearly ended, it extends congratulations if your record has been good, its sympathy, if ill. You, like it, have been making history. You as pioneer students have helped to found a College; to rear an institution of higher learning here in this bright Sunland’. The keynote speaker at the college commencement ceremony added that it did not task the imagination to predict that the time was not far distant when San Diego College of Letters would take rank among the leading institution of learning in the country.

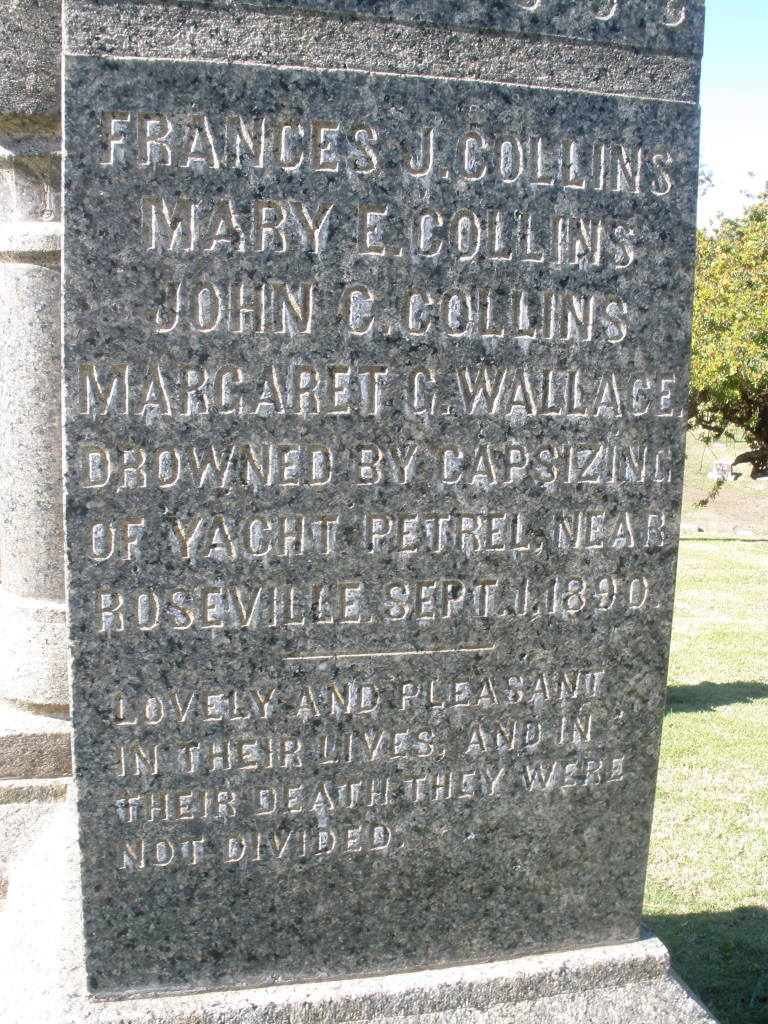

The second academic year opened in September 1889 with a few additions to the faculty and many of the same students. A new college building was opened in January 1890, financed by and named for Oliver J. Stough, a real estate investor with interests in Pacific Beach. Stough Hall became the popular venue for students’ elocution contests and musical recitals, watched by citizens who arrived in special trains from downtown San Diego. Closing exercises for the college’s second academic year were held in Stough Hall in June 1890.

During the summer of 1890 a number of changes were made in the administration and corporate structure of the college. The San Diego Union reported that the original partners in the college company, Harr Wagner, C. S. Sprecher and F. P. Davidson, transferred their interests in the company to ‘eastern parties’. Wagner and Sprecher both resigned from the faculty to devote their full attention to the Golden Era. Davidson remained at the college in a caretaker role, representing the new ownership, which was expected to lift the burdensome debt from the young but vigorous institution.

When classes resumed for the fall term in September 1890 about 50 students were enrolled, the majority from Pacific Beach or elsewhere in San Diego. In December the San Diego Union reported that the term had closed and all but two or three students from the East had dispersed to their homes for the holidays. If the students did return for the second term in January 1891 they did not remain for long. In March 1891 the Union reported that Captain and Mrs. Woods had moved in and taken charge of the College of Letters and added that Mrs. Woods had been a teacher there for some time and the college would be in good hands. There was no explanation for why this was necessary and no further news from the college for the remainder of what would have been the academic year. Although the San Diego Union reported in August 1891 that a Prof. Vinton Busby from Indiana State University would accept the presidency of the college and had arrived in town to make final arrangements, these arrangements apparently fell through and the San Diego College of Letters in Pacific Beach never reopened.

James W. Reid’s lawsuit over the debt he was owed for design and construction of the first college building had been decided in Reid’s favor in March 1891 and with no other assets available to satisfy the judgement the court ordered the sheriff to seize the college company’s real estate. The college campus property was subsequently auctioned at the court house door on three separate occasions over the next five years before being acquired in 1898 by Rev. William L. Johnston of the Pacific Beach Presbyterian Church, as trustee for Pacific Beach College, an organization of residents determined to reestablish an institution of learning there. Some alterations were made to the college buildings, including a tower on Stough Hall, but no progress was made toward reestablishing the college. Instead, the campus was used for various purposes including a Y.M.C.A. summer camp. In 1901 it was described as the College Inn, with W. Johnston as secretary and manager, and local news items occasionally commented on its guests (‘Mr. and Mrs. Sewel of Los Angeles spent last week at the College Inn’). Stough Hall became the center for dances and other gatherings in Pacific Beach.

In 1903 Folsom Bros. Co., a real estate developer which had recently acquired the Fortuna Park subdivisions south of what is now Pacific Beach Drive, purchased most of the rest of Pacific Beach from O. J. Stough (the Union headline read ‘Pacific Beach Has Changed Owners’) and began a program of improvement and development to enhance the value of their investment. In April 1904 they also leased the college campus (with option to buy) from W. L. Johnston and announced plans to develop the former college buildings into a first class resort. While this development was underway they held a contest to choose a name for their new resort. The name chosen (for which the lucky winner received a $100 lot in Pacific Beach or $100 in gold) was Hotel Balboa. Folsom Bros. exercised their option to buy the property in 1905 and over the next few years alterations and repairs were said to have added greatly to its attractions. In 1907 the hotel grounds were landscaped and the surrounding streets graded, ‘sidewalked’ and lined with palms trees (some of which are still growing). However, despite the efforts of Folsom Bros. Co., the Hotel Balboa also was not a success.

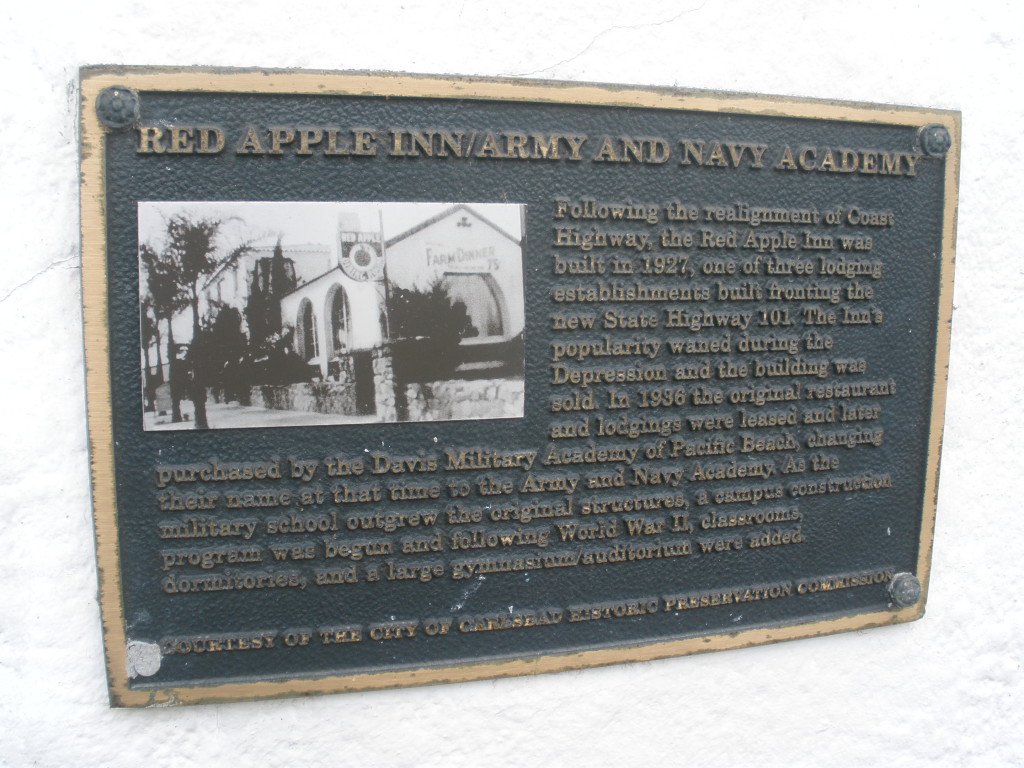

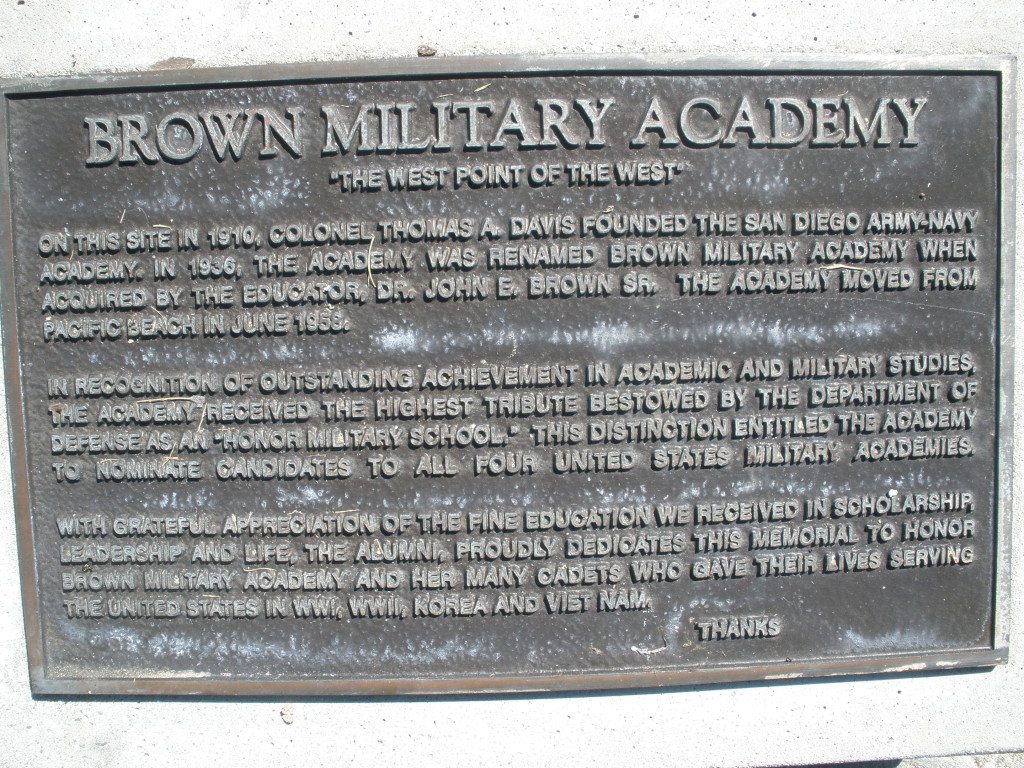

In 1910 Capt. Thomas A. Davis leased the buildings and grounds and started the San Diego Army and Navy Academy with 13 students and himself as the only instructor. Unlike its previous occupants, the military academy thrived and grew over the years. Davis purchased the property in 1921 and eventually added a number of larger buildings which surrounded and dwarfed the original college buildings. During the depression of the early 1930s the academy, like the college before it, was unable to repay the costs of its building program and was acquired by John Brown Schools and renamed Brown Military Academy. In the 1950s Pacific Beach growth encroached on the academy and in 1958 it moved to a new location in Glendora.

The new owners of the college campus property proceeded with plans to convert it into a shopping center and in August 1958 the San Diego Union reported that workmen razing one of the buildings on the site had found a baking soda tin in its cornerstone containing papers dating to 1887, including San Diego newspapers and a Pacific Beach subdivision map.