The quaint cottage at 2104 Diamond Street, overlooking the corner of Diamond and Noyes, is one of the first houses ever built in the Pacific Beach subdivision and may be the oldest one still standing. It is also associated with some of PB’s most distinguished early-day residents.

In 1887, at the height of San Diego’s great boom, a ‘syndicate of millionaires’ bought up the property we now know as Pacific Beach, incorporated as the Pacific Beach Company and, in October 1887, filed a map for the Pacific Beach subdivision. In December 1887 they held an opening sale which the San Diego Union called the most successful in the history of San Diego real estate transactions, with over $200,000 worth of lots ‘disposed of’. Not only that but the paper reported that the buyers were all legitimate investors, many of them intended to improve their lots and five handsome residences were to be erected immediately.

For some reason, perhaps because the lots were sold on an installment basis, the first deeds were not actually recorded until April 1888, but one of the first deeds that was recorded, on May 18, 1888, was for lots 39 and 40 of Block 140, the property under what is now 2104 Diamond Street (on the 1887 map it was Alabama Avenue, at the corner of Thirteenth Street). The grantee was Madge Morris Wagner and the consideration was $250 gold coin of the United States of America.

Madge Morris Wagner was the wife of Harr Wagner, editor of the Golden Era, a literary magazine established in San Francisco in 1852. Wagner had purchased the Golden Era in 1882 and in 1887 he moved it to San Diego, explaining to his subscribers that San Diego was destined to become a great city and the Golden Era was determined to contribute to and benefit from the city’s growth. In a May 1887 editorial he explained the benefits to a city of an institution of higher learning and suggested that San Diego was large enough to support one. To implement this vision, Wagner convinced the Pacific Beach Company to include a college in the plans for their new community. The October 1887 subdivision map did set aside a four-block College Campus in the center of town, where Pacific Plaza is now, and the Pacific Beach company deeded it to the college company founded by Wagner and his partners, C. S. Sprecher and F. P. Davidson. The cornerstone for the San Diego College of Letters was laid in January 1888 and the original college building was completed and opened for 37 students in September 1888.

As a founder and professor at the college Harr Wagner would have been one of the first residents of Pacific Beach, and the house built on the Wagners’ property at the corner of Alabama and Thirteenth, a short walk from the college, may have been one of the handsome residences expected to be erected immediately, possibly as early as 1888. Although they had lived at 2229 E Street downtown when the 1887-88 San Diego City Directory was printed, their residence was listed as Pacific Beach in the 1889-90 directory.

From 1888 to 1892 John D. Hoff’s Asbestos Company was located near the present-day intersection of Garnet Avenue and Soledad Mountain Road in Pacific Beach. Hoff’s asbestos works manufactured paints, boiler coatings and other products incorporating asbestos. A March 1889 ad in the San Diego Union listed some well-known persons having Hoff’s asbestos goods in use and one of these well-known persons was Harr Wagner. Although the ad doesn’t specify what goods were in use or where they were being used, several of the other references on this list were located in Pacific Beach, including the College of Letters and the Presbyterian Church. It may be that Harr Wagner had used Hoff’s asbestos paint to protect and fire-proof his house, just a few blocks down the street from Hoff’s factory, sometime before March 1889.

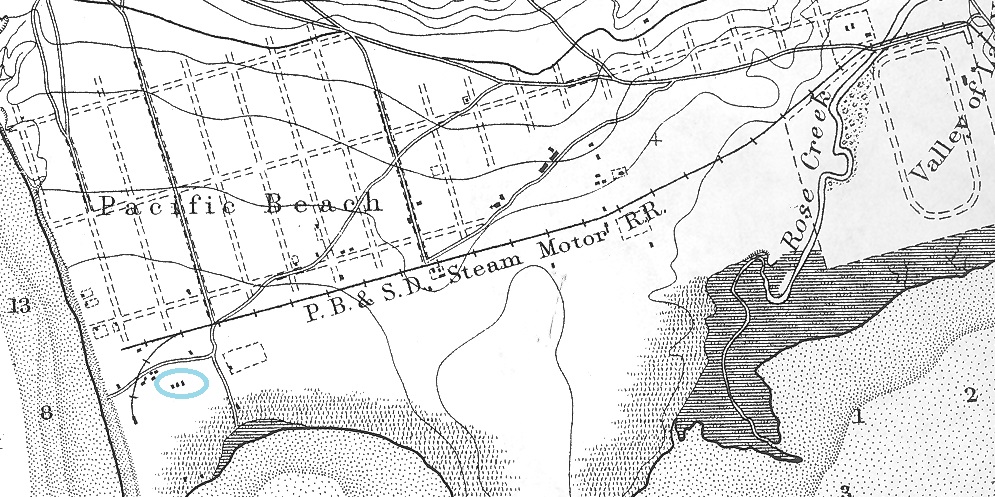

There was certainly something there by the end of 1889. A U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey map of the Pacific Coast from False Bay to La Jolla, dated 1889, covered Pacific Beach and included cultural features such as buildings and roads. One of the buildings that showed up on this map was at Alabama and Thirteenth, presumably the Wagners’ home. The map also shows two buildings labeled ‘University Buildings’ a few blocks to the west. The original college building had been built in 1888 but a second building, Stough Hall, was begun in September 1889 and completed in January 1890. On the map, the western-most of the two university buildings is in the appropriate location for Stough Hall, but in the wrong orientation, aligned with the original college building. Stough Hall was actually aligned with College (now Garnet) Avenue and at an angle to the original building. Apparently the cultural features on the map, which included the house at Alabama and Thirteenth, had been field-checked in late 1889 when the location of Stough Hall was apparent but its final footprint was not.

Madge Morris Wagner was a successful writer in her own right who had long contributed articles and poems to the Golden Era. In 1889 she began work on a novel, A Titled Plebian, which was completed in July 1890 and published in the December 1890 issue of the Golden Era. An ad for Hoff’s asbestos company in the same issue of the Golden Era said that the author had written the narrative at her Villa Home, Pacific Beach – made attractive and beautiful – both interior and exterior – by Hoff’s Glossy Asbestos Paints. ‘The Mirror Walls through her open casement windows reflect on the shores of the Bay – a net-work of buildings – alive with busy men Amalgamating, Packing and Shipping Hoff’s Asbestos Paints and Lubricants’. The house at 2104 Diamond, on a bank above the street, still has a view of the shores of Mission Bay that would have included the site of the asbestos works, alive with busy men in 1889 and 1890.

The development of Pacific Beach and the establishment there of the San Diego College of Letters had anticipated that the population growth seen during San Diego’s great boom would continue indefinitely. Unfortunately for the developers, and for the college, the boom suddenly ended in 1888, a few months after the Pacific Beach Company’s opening sale and before the college had even opened. In addition to the grant of the College Campus itself, the company’s endowment to the college had included hundreds of lots to be sold by the college to fund future operations. The end of the boom, however, caused a collapse in the San Diego real estate market, including Pacific Beach lots, drying up this expected source of funding. The college managed to stay open for two years but in the summer of 1890 Harr Wagner and his fellow founders, Sprecher and Davidson, transferred their interest in the college company to ‘eastern parties’, presumably with deeper pockets. Wagner and Sprecher resigned their positions on the faculty to devote their time to the Golden Era, where Wagner was Editor and Sprecher became Associate Editor. Davidson remained at the college to represent the new owners.

In November 1890 Harr Wagner was elected County Superintendent of Schools and Madge Morris Wagner took over as editor of Golden Era. Wagner’s tenure as superintendent was notable for his progressive educational policies, but he was defeated for reelection in 1894 and eventually decided to take the Golden Era back to San Francisco.

In October 1891 the San Diego Union reported that Harr Wagner had moved his household goods from his home in Pacific Beach to the corner of Walnut and Albatross, and that Mr. Havice had moved into the house vacated by Mr. Wagner (George Havice was married to Harr Wagner’s sister Jennie). The Havices also owned an entire block, Block 213, a few blocks to the south, between what are now Garnet Avenue and Noyes, Hornblend and Morrell Streets. In 1892 the San Diego Union reported that Havice had set out lemon trees on his property, introducing the lemon industry that was to revive the economy of Pacific Beach and sustain it over the next decade.

Although the Wagners had moved to the Bankers Hill area, they still owned the property in Pacific Beach where in 1893 city records listed improvements assessed at $240, presumably the value of the house at the corner of Alabama and Thirteenth. In 1894 the Wagners sold the property to Elizabeth Dunn of Columbus, Ohio, and from 1895 to 1904 city records listed it under her name, with improvements continuing to be assessed in the range of $175 to $200. Miss Dunn, however, remained in Ohio and the property, and the house, has always been associated more with her sister, Dr. Martha Dunn Corey, a Pacific Beach pioneer who was also the region’s first resident physician.

In 1892 the Pacific Beach Company had begun selling ‘acre lots’ in the outlying areas of the community, tracts of about 10 acres intended for agricultural development. One of the first acre lots to be sold, in February 1892, was Acre Lot 19, granted to Lucien Burpee in trust for Martha Dunn Corey and her children (Acre Lot 19 is now C. M. Doty’s Addition, south of Kate Sessions Park and surrounded by Kendall, Beryl and Lamont streets). Dr. Corey and her husband, Col. George H. Corey, followed George Havice’s example and developed Acre Lot 19 into one of the first lemon ranches in Pacific Beach. In 1895 the city leased George Corey an additional 20 acres of the city land adjoining their property (that became Kate Sessions Park) on the condition that he clear it. While operating their lemon ranch the Coreys presumably lived in the ranch house on the property, while the cottage on Block 140 was rented out (the Evening Tribune reported in 1898 that Mr. and Mrs. Conover had leased Dr. Corey’s house on Alabama Street).

In 1900 the Coreys moved to Marion, Ohio, where Dr. Corey practiced medicine, but in 1906, by then a widow, she returned from Ohio and established a medical practice in La Jolla, with a home and office at 7816 Girard Street. She also formally acquired the property and the home at the corner of what had become Diamond and Noyes streets from her sister. City records show Martha Dunn Corey as the owner beginning in 1905; the deed transferring the property was recorded in 1908.

Dr. Corey lived and worked for nearly twenty more years in La Jolla, which she was said to have considered her only true home, but she also retained the house on Diamond and apparently even occupied it intermittently. The San Diego city directory for 1913 listed her address as Diamond ne cor Noyes, Pacific Beach (other directories from 1908 to 1924 listed her La Jolla address) and the San Diego Union reported that for Christmas 1913 Dr. Corey and her three sons motored to their home in Pacific Beach and prepared dinner for Mrs. S. C. Dempsey and her family (Sally Dempsey had a real estate office at 7818 Girard, next door to Dr. Corey and presumably her tenant).

Dr. Corey occasionally took time off to be with her sons, and some of that time was spent in Pacific Beach. In 1914 the Evening Tribune reported that Dr. Corey would accompany her sons Gardner and Fred Corey to university at Berkeley and would probably remain with them until Christmas. Her La Jolla residence would be leased and Dr. F. H. Parker had come to La Jolla to practice in Dr. Corey’s place. In December, 1914, the news was that she had returned from Berkeley to occupy her cottage in Pacific Beach where her sons Fred and Gardner were expected to spend the holidays. She would resume her practice in both La Jolla and Pacific Beach. In February, the report was that Dr. Corey ‘who now resides in Pacific Beach’ had opened a new office at the corner of Girard and Prospect. In May, her sons were expected to return to La Jolla and Pacific Beach to pass their vacation with their mother.

In 1917, after war was declared again Germany, she accompanied her son Dunleigh, also a physician, to Honolulu, where he was surgeon aboard the USS Schurtz (the Schurtz was a former German cruiser interned since 1914 and seized by the navy in 1917). They were said to have a pleasant apartment in town, with Lt. Corey commuting to his ship each day. Back in La Jolla, in 1923, her son Fred Corey married Miss Ruth Richert, who had grown up in the house that still stands at the other end of Block 140, at the corner of Diamond and Olney. Gardner Corey was also married in 1923, to Miss Mary Scripps, daughter of Fred and Emma Scripps who lived in Braemar Manor on Mission Bay where the Catamaran Resort Hotel now stands.

When Dr. Martha Dunn Corey retired in 1925 she moved back to Pacific Beach, not to Diamond Street but to the house on Grand Avenue at Bayard that is now the Needlecraft Cottage. Her former home in La Jolla is also still standing, although no longer at its original location on Girard Street, in the ‘downtown’ La Jolla business district. It was moved, first to Draper Street and then to The Heritage Place property at the corner of La Jolla Boulevard and Arenas Street.

In 1922 Dr. Corey had sold the house at 2104 Diamond to Ed Ritchie, a construction supervisor for the San Diego and Arizona Railway who went on to supervise construction of the San Diego Electric Railway line through Mission Beach and Pacific Beach to La Jolla in 1924. From 1928 to 1930 his wife Josephine served as president of the Pacific Beach Women’s Club (formerly the PB Reading Club), following in the footsteps of its other illustrious leaders like founder Rose Hartwick Thorpe and Mary Stoddard Snyder. In 1926 the Ritchies added a garage and in 1928 the house was re-roofed.

When Ed Ritchie died in 1937 the house was already nearly 50 years old. At that time there were still only three other homes on the same block of Diamond Street (one of which was the Richerts’), and only 40 on all of Diamond Street. Mrs. Ritchie moved in with a daughter, also at a Diamond Street address two blocks away, and her former home was rented out, mostly to aircraft workers working at Consolidated Aircraft or Rohr during World War II. Many more aircraft workers were housed in the hastily constructed federal housing projects surrounding Block 140 on the north and east, and many of these workers remained in Pacific Beach after the war, contributing to the housing boom that has never really stopped. Today there are hundreds of homes, condominiums, town houses and apartments on Diamond Street, but the cottage at the corner of Diamond and Noyes may have been the first.