Raymond Chandler was an author and screenwriter best known for his mystery novels featuring the ‘hard-boiled’ private detective Philip Marlowe. His first novel, The Big Sleep, was published in 1939 and was followed in the 1940s by four others, Farewell, My Lovely, The High Window, The Lady in the Lake and The Little Sister. The Long Goodbye, probably his best novel, was published in 1954.

Chandler’s publishing career began in Los Angeles and his novels were mostly set in the Los Angeles area, where Chandler and his wife Pearl Eugenia (better known as Cissy) had lived since the 1920s. In 1946, the Chandlers moved to La Jolla where they lived in a home overlooking the beach on Camino de la Costa. Cissy Chandler was much older than her husband and she died in 1954 at the age of 84. Raymond Chandler was devastated by her death; he resumed his heavy drinking, attempted suicide, and engaged in increasingly erratic behavior, which included marriage proposals to numerous women. His writing also suffered, although he did manage to publish a final novel, Playback, in 1958.

Playback was another Philip Marlowe mystery but it differed from his previous work in that much of the action took place away from Los Angeles, in a suburb of San Diego that he called Esmeralda but which is easily recognizable as La Jolla. Although not his best literary work it is interesting for his observations of the town that had been his home for the preceding decade.

In the novel Marlowe was hired to tail a young woman after her arrival at Union Station in Los Angeles, but instead she got back on a train and continued to San Diego where she hired a taxi. Marlowe, who had followed her on the train, also hired a taxi and his driver learned from the dispatcher that the girl’s cab was going to Esmeralda, twelve miles north on the coast. Their destination was a hotel joint called Rancho Descansado, which consisted of bungalows with car ports, some single, some double, with rates that were pretty steep in season.

They headed north on Highway 101 to Torrance Beach, where they swung out toward the point. After passing through a small shopping center, some expensive houses and a 25 mile zone, his driver cut to the right, wound through some narrow streets and slid down into a canyon with the Pacific glinting off to the left beyond a wide beach. They stopped at a sign that said “El Rancho del Descansado” where Marlowe got out and checked in.

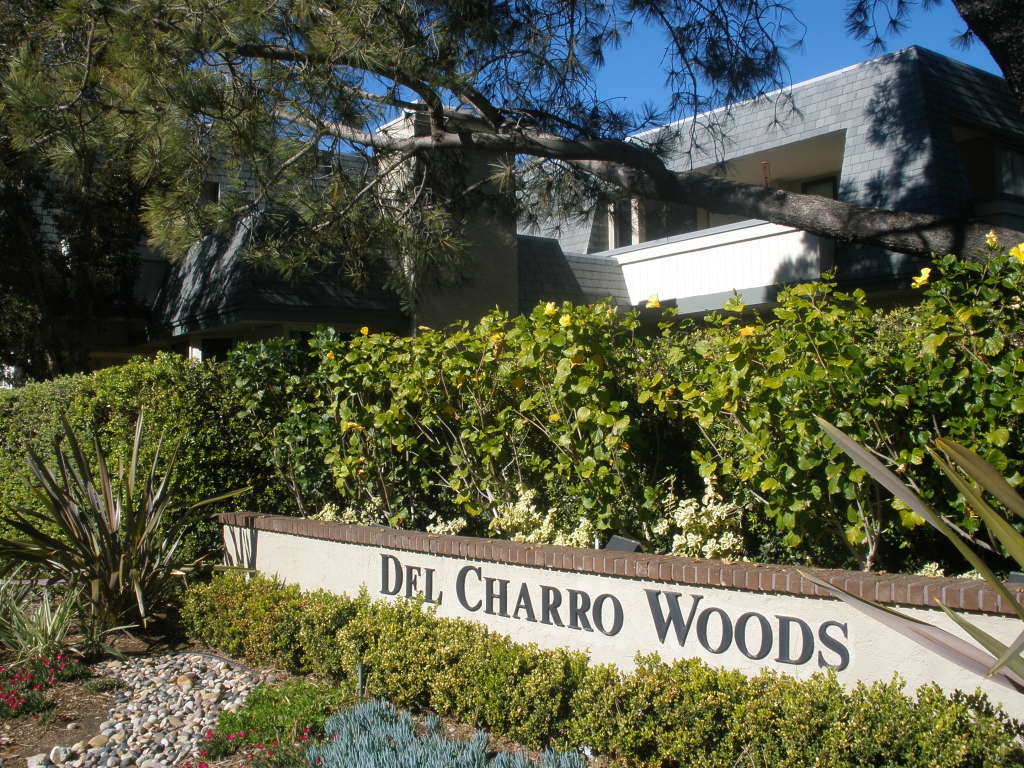

This drive traces a route through Pacific Beach, Bird Rock and the back streets of La Jolla to Torrey Pines Road. Beyond La Jolla Shores, where the Pacific would be visible beyond a wide beach on the left, and where Torrey Pines Road enters La Jolla Canyon, they would have found Rancho del Charro. Originally a riding stable and practice ring, it had been enlarged in the late 1940s and early 1950s into a motor hotel with riding facilities and guest cabanas. The site, where La Jolla Parkway merges with Torrey Pines Road, has since been redeveloped and is now a condominium community.

At Rancho Descansado Marlowe learned that his subject, Betty Mayfield, was being blackmailed. He went to her room where she threatened him with a gun and knocked him out with a whiskey bottle while he was trading punches with the blackmailer. However, Marlowe had learned that she was to have dinner that evening at the Glass Room, and of course Marlowe made it his business to be there too.

The Glass Room was on the beach, the entrance lobby was on a balcony which looked down over the bar and a dining room, and on one side was an enormous glass window where the view would have been sensational on a clear night with the moon hanging over the water. This is a perfect description of the Marine Room, open since 1941, where the enormous glass window still looks out over the ocean from the La Jolla Beach and Tennis Club.

At the Glass Room the blackmailer, Larry Mitchell, behaved boorishly, Betty called him a drunken slob, he slapped her face and was asked to leave. Betty told him in a voice the whole joint could hear that the next time he did that he should wear a bullet-proof vest, never a good idea in a murder mystery where the subject may turn up dead, like Mitchell did later that night.

Betty had checked out of the Rancho Descansado after the scene in her room and checked in to the Casa del Poniente. Later that night she found her way back to the Rancho and knocked on Marlowe’s door to ask for help; Larry Mitchell’s body was lying across a chaise on her balcony. She showed him her gun, which was missing one cartridge. They drove to the Casa where Betty entered through the lobby and Marlowe went in through the garage and climbed up the fire stairs. Betty popped sleeping pills and dozed off while Marlowe checked the balcony and found no body. After searching her bag and removing the rest of her pills Marlowe decided to return home to Los Angeles, taking the two-car diesel job that makes the run to L.A. non-stop.

The Casa del Poniente was set on the edge of the cliff, separated only by a very narrow walk, so Betty’s balcony hung right over the rocks and the sea. It was set in about seven acres of lawn and flower beds near a bathing beach with a small curved breakwater where people would lie around on the sand and kids ran around screaming. Betty’s room was on the twelfth floor, and there was another floor above it. Apparently it was very exclusive; a typical room rate was $14 a day, $18 in season.

No hotel in La Jolla fits this description but a blend of two hotels from the 1950s might have served as a model. The Casa de Mañana was built in 1924 near Seal Rock, separated from the cliffs not by a narrow walk but by the width of Coast Boulevard. It occupies an entire block which may be around seven acres and has a lawn and flower beds, but its low-lying Mission-style architecture did not rise above three stories. An exclusive hotel in its day, the Casa de Mañana is still there but has been a retirement home since 1953. And kids no longer scream at the the bathing beach with the curved breakwater just across Coast Boulevard from the Casa; today the Children’s Pool is reserved for sea lions to lie around on the sand.

The La Valencia Hotel on Prospect Street, also built in 1920s, is nowhere near the edge of the cliff but it is built into the side of a hill and from the bottom of the hill to the top of the tower may have thirteen floors. A luxury hotel then and now, the La Valencia would probably have been the model for Marlowe’s observations of the guests in the lobby; dedicated hotel lounge sitters, usually elderly, usually rich; women with enough ice on them to cool the Mojave Desert and enough make-up to paint a steam yacht and their men looking gray and tired, probably from signing checks.

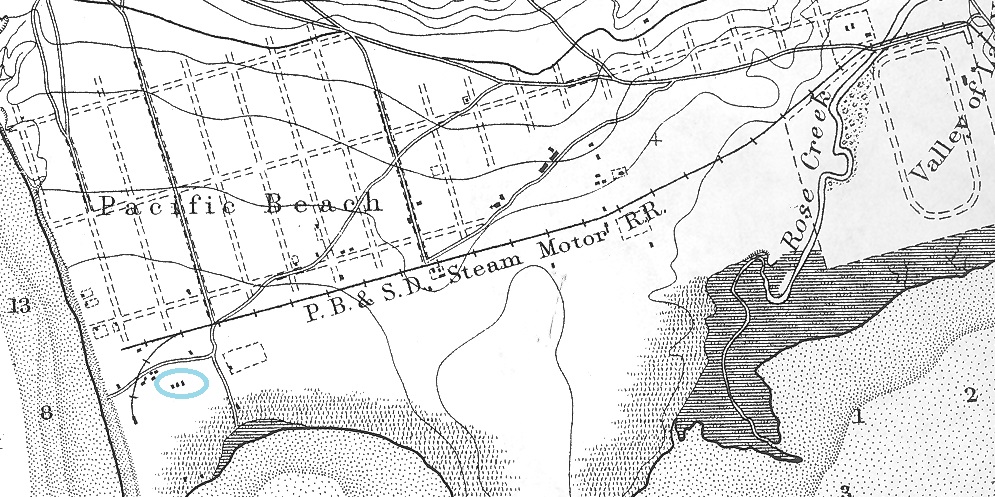

The next day Marlowe drove back to Esmeralda and the Casa del Poniente and again made contact with Betty. They decided to drive up into the hills for a talk and their route took them down a dead-end street with old streetcar tracks still in the paving. They turned left up the hill at the high school. This would have been the corner of Fay and Nautilus Streets, east of La Jolla High School, where the tracks of the former San Diego Electric Railway line to La Jolla remained embedded in Fay Street into the 1960s. Between 1924 and 1940 the streetcar line had run from San Diego to La Jolla via Mission Beach, Pacific Beach and Bird Rock, and along Fay Street from the high school to a terminal on Prospect. The portion of the right-of-way between Nautilus Street and Camino de la Costa in Bird Rock is now the La Jolla Bike Path.

While Marlowe was following Betty Mayfield around Esmeralda, he himself was being shadowed by another private investigator, Goble, a middle-sized fat man in a dirty little jalopy. To find out why, Marlowe allowed Goble to tail him, taking it easy so he wouldn’t blow a gasket. About a mile from the hotel there was a restaurant, The Epicure, with a low roof, a red brick wall to shield it from the street, and a bar. The entrance was at the side. Marlowe parked and went in and when Goble joined him they traded wisecracks over drinks and the plat du jour, meat loaf. Su Casa, a restaurant on La Jolla Boulevard between Playa del Norte and Playa del Sur, about a mile south of ‘downtown’ La Jolla, has a low roof, a wall, a side entrance and a bar, and in the 1950s it was called The Connoisseur (update, the building that had been The Connoisseur and Su Casa was demolished in 2022).

The night when Marlowe had entered the Casa del Poniente through the garage he had come across the parking attendant passed out in a Packard surrounded by the honeyed reek of well-cured marijuana. The next day Marlowe returned to question him and posed as a pusher. The attendant told Marlowe where he lived; a flea bag of an old frame cottage on Polton’s Lane, an alley behind the Esmeralda Hardware Company. Later, when Marlowe went to Polton’s Lane, he found the man dead, apparently having hanged himself. The La Jolla Hardware Company was located on the west side of Girard Street in the 1950s, between Prospect and Silverado. The alley behind it is actually called Drury Lane and even today there is a frame cottage there, although hardly what one would call a ‘flea bag’.

Chandler’s Esmeralda not only looked like La Jolla but what he described of its heritage was recognizable as well. In one chapter, Marlowe recalls what he was told by a man who had been there for thirty years. Originally it had been so quiet that dogs slept in the middle of the boulevard and you had to get out and push them out of the way. Then the town began to fill up, first with old women and their husbands and then, after the war, by guys that sweat and tough school kids and artists and country club drunks and them little gifte shoppes. The town was dominated by a wealthy family, the Hellwigs, and especially by Miss Patricia, who gave the town the hospital, a private school, a library, an art center, public tennis courts and God knows what else. In the actual La Jolla Miss Patricia Hellwig would have been Miss Ellen Browning Scripps, who donated Scripps Memorial Hospital, The Bishop’s School, and many other La Jolla landmarks, sometimes in association with her wealthy brothers and sisters. The list of landmarks donated by the Scripps also includes the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, which became the nucleus of the University of California San Diego.

Chandler’s characters also expressed opinions on Esmeralda society. During their dinner at The Epicure, Goble told Marlowe that he was smart, got around and found things out. One of the things he found out was that Esmeralda was one of the few places left in our fair green country where dough ain’t quite enough. In Esmeralda you got to belong, or you’re nothing; you got to have class. A guy had made five million fish in the rackets and built some of the best properties in town, but he didn’t belong to the Beach Club because he didn’t get asked. So he bought it (the same guy, Brandon Clark, also owned the Rancho Descansado and the Casa del Poniente).

In the end Betty Mayfield’s pursuers really had nothing on her. Larry Mitchell was dead; not shot but fallen from Clark’s terrace on the floor above Betty’s balcony and his body removed to where no-one would ever find it. He wasn’t likely to be missed. Marlowe rescued Goble from a hired thug who was also lying in wait for Marlowe. After a showdown with Clark, who was apparently responsible for Mitchell’s death and the disappearance of his body, Marlowe drove home to Los Angeles, not doing more than ninety except he may have hit a hundred for a few seconds now and then.

Raymond Chandler died in 1959 at Scripps Clinic in La Jolla and was buried at Mount Hope Cemetery in San Diego. As his life had unraveled after Cissy’s death in 1954 one of the many loose ends he failed to tie up was having her buried; she had been cremated but her ashes were left in storage at Cypress View Mausoleum. After nearly sixty years this omission was finally corrected on February 14, 2011, Valentine’s Day, when her ashes were buried next to his grave at Mount Hope.