When Pacific Beach was founded in 1887 its founders also built a railroad to connect the new community with downtown San Diego. The San Diego, Old Town and Pacific Beach Railway ran between the site of the current Santa Fe station on Broadway and a depot near the foot of Grand Avenue in Pacific Beach, following a route east of Mission Bay and around the race track at the northeast corner of the bay, then along today’s Garnet, Balboa and Grand Avenues to the beach. In 1894 the railroad was extended to La Jolla along what are now Mission Boulevard, La Jolla Hermosa Drive, Electric Avenue and Cuvier Street to a station on Prospect Street. The Pacific Beach and La Jolla railroads became the Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railroad in 1906 (although the tracks never advanced beyond La Jolla). In 1907, after the race track in Pacific Beach had closed, the line was shortened by cutting through the former race course over what is now Grand Avenue from Mission Bay Drive to Lamont Street.

The trains to Pacific Beach and La Jolla consisted of one or more coaches and a mixed baggage car pulled by small steam locomotives, although between 1907 and 1914 some of the daily trips were made by McKeen gasoline-powered rail cars. In the days before paved roads and the automobile, these trains were the only practical way to travel to and from San Diego. However, after the turn of the twentieth century automobiles became increasingly popular and the roads were improved, giving north coast residents another travel option. In 1919, claiming that receipts from operations were insufficient to meet operating expenses and interest, the LA & SD Beach Railway received permission to discontinue service and dismantle its tracks. Although civic organizations in San Diego, Pacific Beach and La Jolla opposed its closure, none were able to offer an alternative and the railroad was scrapped.

Efforts began almost immediately to re-establish a rail link between San Diego and its northern suburbs. In 1915 a bridge had been built across the entrance to Mission Bay and an electric railway line called the Bay Shore Railroad built from Ocean Beach over the bridge and through Mission Beach as far as Redondo Court. The Bay Shore Railroad connected with the Point Loma Railroad, an electric street railway which ran between downtown San Diego and Ocean Beach. In January 1919 a group calling itself the La Jolla Electric Line proposed laying 2100 feet of new track to extend the Mission Beach line to Grand Avenue in Pacific Beach, from where it could continue to La Jolla over the former LA & SD Beach right-of-way. These new sections would then be electrified, completing an electric railroad all the way from San Diego to La Jolla.

The La Jolla electric company’s proposal of 1919 was never implemented but the concept of an electric railroad between San Diego and La Jolla via Mission Beach was adopted a few years later by the San Diego Electric Railway Company, operator of San Diego’s extensive street railway system and part of the Spreckels commercial empire. In March 1923, the SDER and the Mission Beach Company jointly announced what was called the greatest single development project since the preparations for the Panama-California Exposition in Balboa Park; a project to make Mission Beach the finest and highest class beach resort in America – an all-year resort open and operating 12 months in the year. This project would include express electric railway service to and from San Diego, much of it double tracked and largely on private right-of-way. The San Diego common council awarded the SDER a franchise to build the proposed Mission Beach line in April 1923.

The SDER planned to lay tracks on Kettner Boulevard and Hancock Street from Broadway to Witherby Street, along the right-of-way of the former LA & SD Beach line. The tracks would then cross over the Santa Fe railway and the paved Point Loma highway and continue to Ocean Beach on a new route across the mud flats and marshes that are now the Midway district. From Ocean Beach the new line would continue to Mission Beach over the Bay Shore Railroad, which the SDER planned to purchase and absorb.

The SDER plan did not initially propose extending the line beyond Mission Beach, but in May over 700 La Jolla residents signed a petition asking the common council for an extension of the route to their community. At the time the SDER was pressing the city to extend its franchise for 50 years, and it offered to build to La Jolla if the extension was granted. A 50-year franchise covering the SDER’s entire system, including the route to La Jolla, was approved by the council in September 1923.

Construction of the new electric line began in October 1923. The Evening Tribune announced that ‘dirt was flying’ on Kettner Boulevard for the biggest electric railway construction job in the history of San Diego, the double-track speed line to Mission Beach. The Tribune article noted that the project would include extension to La Jolla and construction of a great amusement center in Mission Beach. The new line would have the catenary type overhead wire for pantograph collectors that are specially designated for high speed operation. There would be no grade crossings; a long trestle would bridge the Santa Fe tracks and the Point Loma highway crossing in the Five Points area, and on the La Jolla segment the track would run under the coast highway on Turquoise Street.

Several thousand tons of steel rails began arriving from ‘famous Belgian mills near Liege’ in November, and in December 1923 the SDER began receiving 50 new streetcars specifically designed for the high speeds and flexible operations of the new route, with pantograph collectors and control systems that allowed the new cars to operate individually or in trains which could be coupled and uncoupled rapidly en route. By the end of February 1924 the tracks had reached Turquoise Street in Pacific Beach and a group of city officials, railroad men and business men made a preliminary round trip over the line. Reporters for the local papers who accompanied the dignitaries wrote that there were cheers from every side, hands and handkerchiefs were waved, and cameras clicked as the train rolled through, running as smoothly as a Pullman coach. Claus Spreckels, general manager of the SDER, announced that the line would be in full operation as far as Mission Beach on May 1 and on to La Jolla by July 1.

The new express line was opened as far as Ocean Beach (with a temporary shuttle to Mission Beach) on May 1, 1924 and through service to Mission Beach, Pacific Beach and La Jolla began on July 1. The planned viaduct over the Santa Fe tracks and the Point Loma highway had not yet been built so the new line at first used the Point Loma Railroad’s grade crossing to a point near the Marine base on Barnett Avenue. From there the route crossed open country on a private right-of-way that has since become Sports Arena Boulevard. At Midway Drive, the tracks continued on an elevated causeway through salt marshes along what is now West Point Loma Boulevard but was then the southern shore of Mission Bay. Beyond Famosa Slough the causeway continued directly to Ocean Beach Junction, about where West Point Loma Boulevard now meets Bacon Street. The causeway included bridges to allow circulation of water to the sloughs and wetlands to its south, and the remains of one of these bridges, over Famosa Slough, can still be seen. At Ocean Beach Junction the line split, one branch following the former Point Loma Railroad route into Ocean Beach and the other the Bay Shore Railroad route over the bridge to Mission Beach.

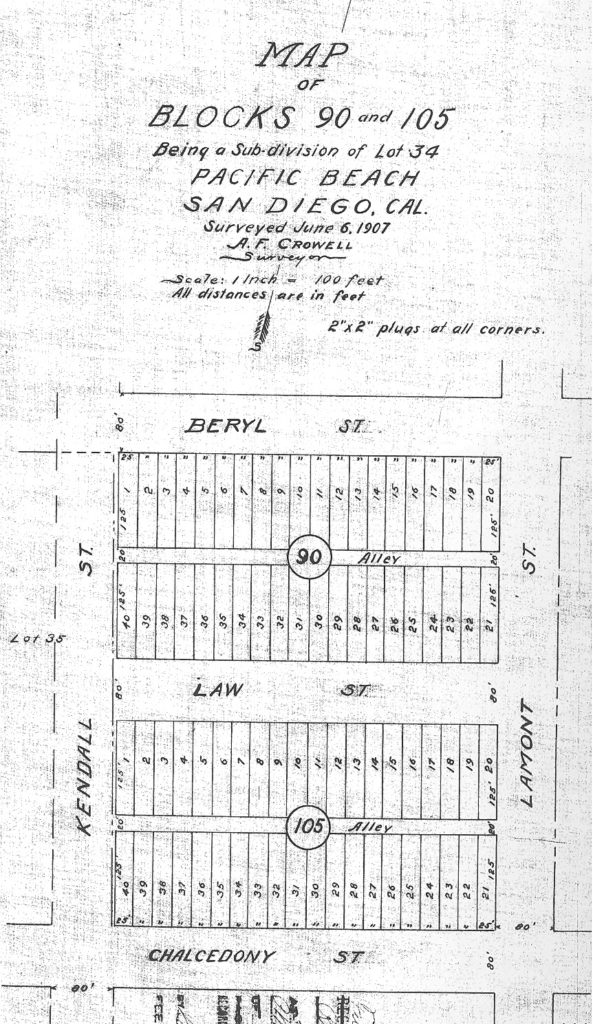

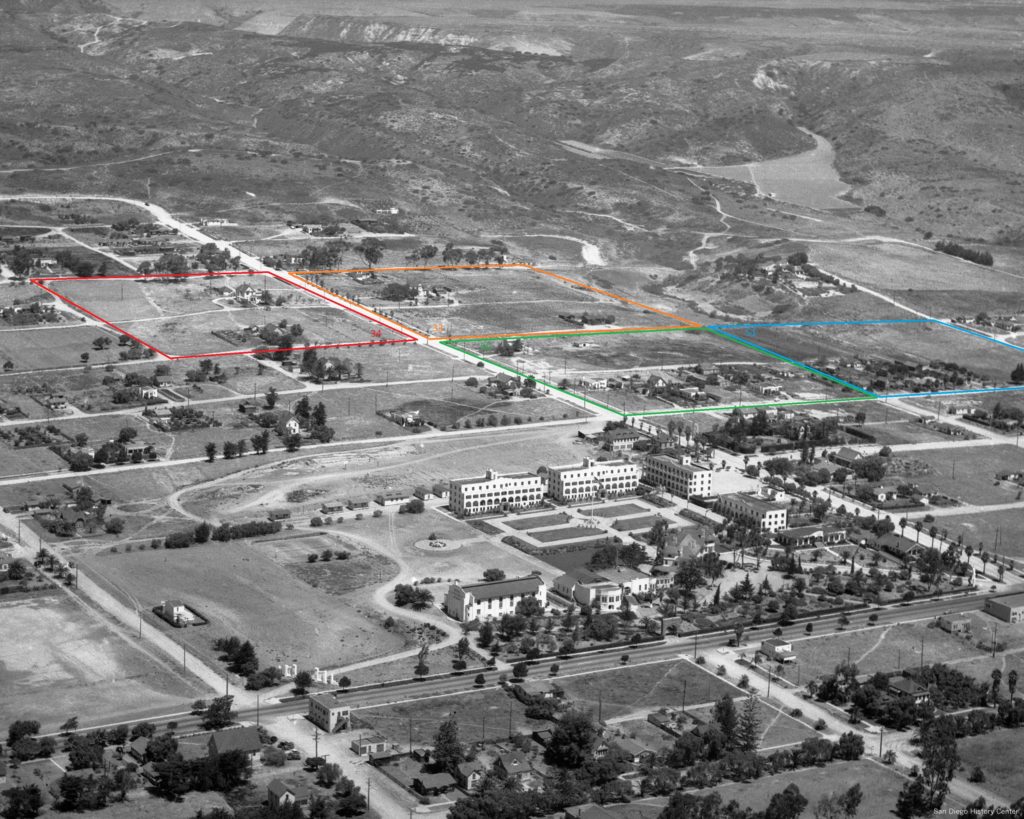

In Mission Beach, the line was built on an elevated strip down the middle of Mission Boulevard, separated from automobile traffic on either side by curbs. The route continued through Pacific Beach on Allison Street, which in 1924 was mostly vacant land; development of the ‘new’ Pacific Beach along the coast, due in part to the arrival of the fast electric line, had not yet begun (Allison Street was ‘opened’ and paved between Pacific Avenue, now PB Drive, and Turquoise Street in 1928, and in 1929 was renamed, becoming the northern extension of Mission Boulevard). At Beryl Street the route curved westward from Allison onto what is now La Jolla Boulevard, where a large concrete culvert was built in Tourmaline Canyon and covered with dirt fill to provide a crossing for the tracks. Turquoise Street at the time was part of the coast highway, paved in 1920, which passed through Pacific Beach on Garnet Avenue and Cass Street and continued to La Jolla and beyond on La Jolla Boulevard. To prevent the disruption and danger of crossing this highway at grade, the SDER constructed a steel viaduct over Turquoise Street. The railway continued on what was then called Electric Avenue and is now La Jolla Hermosa Avenue, following the route of the LA & SD Beach Railway. At Via Del Norte in La Jolla the new line diverged from the old route (which had continued on Electric Avenue and Cuvier Street) onto a private right-of-way that is now the La Jolla Bike Path, and which required a number of cuts to improve the grade. From the end of the private right-of-way near La Jolla High School the line ran on Fay Street to its terminus on Prospect.

Elaborate stations in La Jolla (at Prospect Street and Fay Avenue) and La Jolla Hermosa (at Mira Monte) were finished in 1925. The station at La Jolla Hermosa, which also doubled as a power substation and was designed as a replica of the San Carlos mission at Monterey, is still standing and for many years has been the La Jolla Methodist Church. The three-level viaduct over the Santa Fe tracks and highway to Point Loma was completed early in 1925. With this structure the Santa Fe tracks remained at their original grade, an undercrossing was excavated under the tracks for the highway and a viaduct built to take the electric line over both. The excavation for the highway put the roadway below sea level, and pumps were installed to keep it clear of seepage and runoff. The viaduct, which lifted the electric railway over the tracks of the mainline railway, was 2000 feet long and included 900 feet of embankment, 940 feet of frame trestles and 160 feet of steel girders, supported by massive concrete piers. Witherby Street still passes under the railroad tracks in this same undercrossing, and the base of the concrete piers which supported the viaduct carrying the electric railway over the railroad and Witherby Street can still be seen just to the west of the railroad bridge.

The Mission Beach amusement center opened with great fanfare on May 29, 1925. The station there included a subway under the tracks and Mission Boulevard, protecting passengers from vehicle traffic. At the same time the SDER opened the second track of its double-track route through Mission Beach and, with the completion of the viaducts over the Santa Fe at Witherby Street and the coast highway at Turquoise Street, introduced a new timetable establishing the running time from San Diego to La Jolla at 36 minutes.

The new electric line actually served three routes; No. 14 to Ocean Beach, No. 15 to Mission Beach, and No. 16 to La Jolla, all of which used the same tracks between San Diego and Ocean Beach Junction. Trains which could consist of one or more cars from each of the routes left the Plaza in downtown San Diego under the control of one operator. When they reached Ocean Beach Junction the No. 14 car or cars would be uncoupled and continue on to Ocean Beach with its own operator. The other cars proceeded to Mission Beach where the No. 15 cars (if any) would be dropped off and the No. 16 continue on to La Jolla (the No. 15 route was only used for occasional holiday travel to the Mission Beach amusement park). The coupling mechanism was designed so that the cars could be detached while the train was in motion.

The new fast electric line had been designed to use catenary overhead wires and pantograph collectors instead of the trolley wire and trolley poles that were standard at the time. Catenary wires, like those currently in use on the San Diego Trolley, utilize two wires, the upper one arching between supports and the lower one suspended from the upper one and stretched tight, making it straight and level. Pantograph collectors, frameworks mounted on top of the cars that pressed up against the wire to collect electric current, were thought to be necessary for high-speed operation since trolley poles might bounce out of contact with the wire. However, the pantographs proved to be unsatisfactory; they were of light construction and sometimes collapsed, and tended to damage the overhead wires, especially at switches. They were replaced by trolley poles, which did function adequately with the catenary overhead wires and also allowed the cars to operate on other routes with standard trolley wires.

After the completion of the fast electric line, real estate promoters along its path began emphasizing its benefits to their communities. The developers of Bird Rock, for example, noted that San Diego’s fastest electric line ran through the heart of their beautiful, high, sightly property lying between the hills and the sea, putting it in the ‘path of development’. In Pacific Beach, where development had previously been centered around Lamont Street and the college campus property (then the San Diego Army and Navy Academy, now Pacific Plaza), the promoters of the ‘new’ Pacific Beach around the foot of Garnet Avenue noted that construction of the SDER’s superb fast beach carline swung the business and pleasure sections of Pacific Beach down to the ocean front where they belong, and justified a change of name to ‘San Diego Beach’. Earl Taylor, one of the developers of ‘new’ Pacific Beach, quoted a Saturday Evening Post article that said ‘Wherever electric lines lead out from the city, you find suburban property values enhanced, suburban life made comfortable, and waste land blossoming into homes. The automobile helps. The motor bus helps more. But the trolley and interurban cars are more important still’.

The SDER’s franchise allowed it to haul freight, and in 1925 the Standard Oil Company built a storage yard in the Bird Rock area to be supplied by tank cars delivered by rail. Gaps where a rail spur leading to this storage plant cut through a sidewalk on La Jolla Hermosa Avenue near Forward Street can still be seen. By 1934 the Standard Oil plant was the SDER’s only freight customer and when Standard Oil acquired a fleet of trucks for its oil deliveries SDER received permission to discontinued freight service.

Although parts of the electric railroad were double-tracked, much of it, including the private rights-of-way in La Jolla and in the Midway area, was not, and relied on block signals to prevent collisions between trains traveling in opposite directions. On November 22, 1937, the signals in the Midway area apparently failed and cars traveling to and from Ocean Beach on the single track collided head-on. Visibility had been reduced by heavy fog and the operators failed to see the other car and apply the brakes until seconds before the crash. One car penetrated eight feet into the other and 31 passengers were injured, some seriously. A downed trolley wire added to the danger until the company turned power off on the line.

Whether or not it was the electric railway that caused waste land to blossom into homes, the population in the beach areas served by the electric line did increase throughout the 1930s. Automobile ownership also continued to grow and streets became more congested. In some areas where the streetcars and automobiles shared the road, the traffic forced the high-speed line to operate at slower speeds, impacting service. Also, the growing number of motorists led to increased complaints that the tracks were obstructing vehicle traffic, particularly in Mission Beach, where the line was elevated and isolated from the paved boulevard, leaving little room to drive. Improvement of the roads had also caused the SDER to begin using buses on some routes, including one to La Jolla. The No. 14 streetcar line to Ocean Beach was replaced by buses in 1938 and in January 1940 the SDER company received permission from the city to discontinue service of the No. 16 car line between downtown and its terminus in La Jolla. The SDER was required to remove tracks, wires and overhead structures but, in consideration of the valuable rights-of-way to be conveyed to the city and its substitution of bus service in place of the electric railway service, the SDER was not required to remove its tracks from paved streets. Tracks remained imbedded in the pavement of Fay Avenue in La Jolla into the 1960s and even now potholes can reveal rusted rails beneath the surface of Mission Boulevard.

The last No. 16 train left La Jolla on September 16, 1940; according to longtime passenger and Mission Beach resident Zelma Bays Locker, the motorman on this last run rang his bell all the way into town. In Mission Beach the tracks were removed and Mission Boulevard repaved in 1941, leaving only a 4-foot median where the double-tracked electric railway had once run. According to the San Diego Union, the ‘traffic-clogged two-lane highway’ had become a ‘broad 4-lane arterial which easily is accommodating the heavy beach-area traffic flow’.

The beach-area traffic flow has only become heavier over the ensuing 75 years, and not so easily accommodated, and an electric railway between San Diego and La Jolla is once again under development. The Mid-Coast Trolley is expected to open in 2021, extending San Diego’s modern ‘light rail’ system to the University Town Center shopping mall via the University of California, San Diego campus in La Jolla. Between Old Town and UCSD the new line will follow the route of the Pacific Highway, east of Mission Bay and through Rose Canyon. The station serving Pacific Beach is to be located near Garnet Avenue and Morena Boulevard, east of the I-5 freeway and not far from the old race track site, but on the opposite side of town from where the electric Beach Line ran in the 1920s and 1930s. It will be interesting to see what effect a superb new light rail line will have on the business and pleasure centers of Pacific Beach this time around.