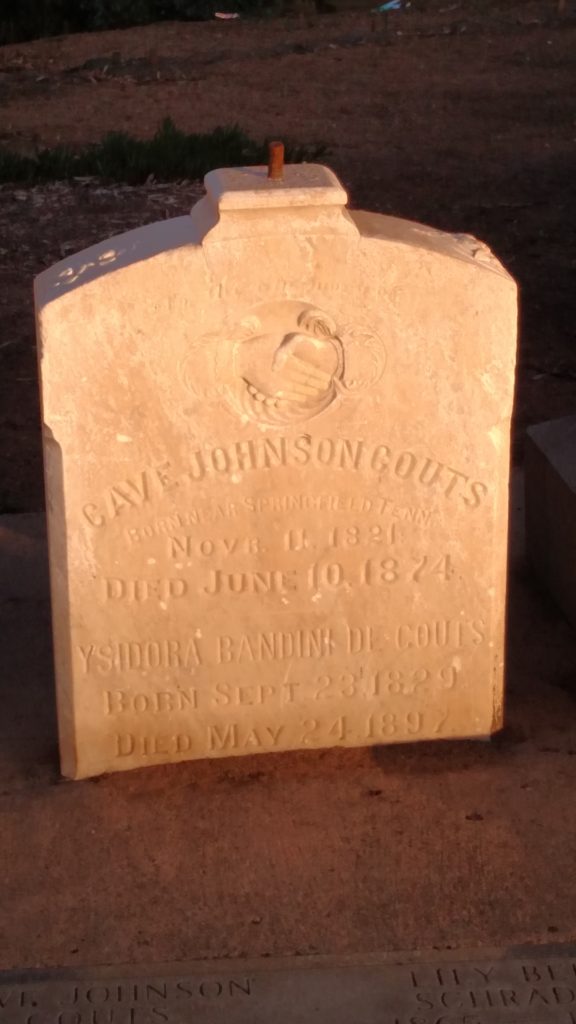

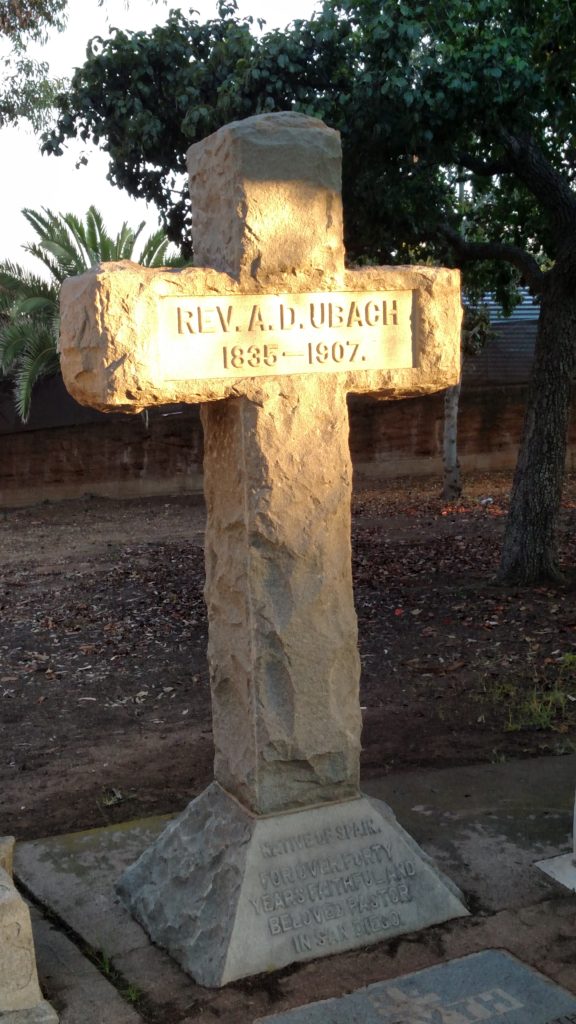

In the 1960s, Richard Pourade, then editor emeritus of the San Diego Union, began a 7-volume history of San Diego. In The Glory Years, the fourth book in the series, published in 1964, he introduced the ‘people who started it all’, who built Southern California in the ‘boom and bust’ years between 1865 and 1900, by visiting an old graveyard ‘where are buried so many of the pioneers who helped to found and build San Diego’. While many headstones were broken or lying on their side, names eroded by the weather, others were well-marked, if seldom visited. The grave of Father Antonio Ubach, the last of the padres, born in Spain in 1835, was marked with a stately monument. Nearby was the grave of Cave Johnson Couts, born in 1821 and a graduate of West Point, and lying beside him his wife, Ysidora Bandini de Couts, daughter of a Spanish Don, the names telling of the ‘melting together of two peoples’. Other names – Ames, O’Brien, Lyons, McCoy, Clark, Hinton, Warnock – told of the great tides of humanity that flooded across a continent in the later 1800s, ‘to find their resting places under eucalyptus trees on a barren hill overlooking a harbor that few people in the world had ever heard of’.

The graveyard Pourade visited was Calvary Cemetery, the old Catholic burial ground next to U. S. Grant Elementary School in Mission Hills. However, even before Pourade had finished his final volume in 1977 that old graveyard had been transformed. The pioneers’ resting place under the eucalyptus trees was no longer a barren hill but a grassy park. No headstones were broken or lying on their sides; most had been removed and dumped at the city’s Mount Hope Cemetery while others, including the monuments of Father Ubach and the Couts family, had been spared and were lined up in a corner of the park in grudging recognition of the park’s original purpose. The names of those believed buried in the cemetery were inscribed on six bronze panels ’dedicated to the memory of those interred within this park’. Those interred within the park remained, beneath the new lawn, sidewalks and parking lot.

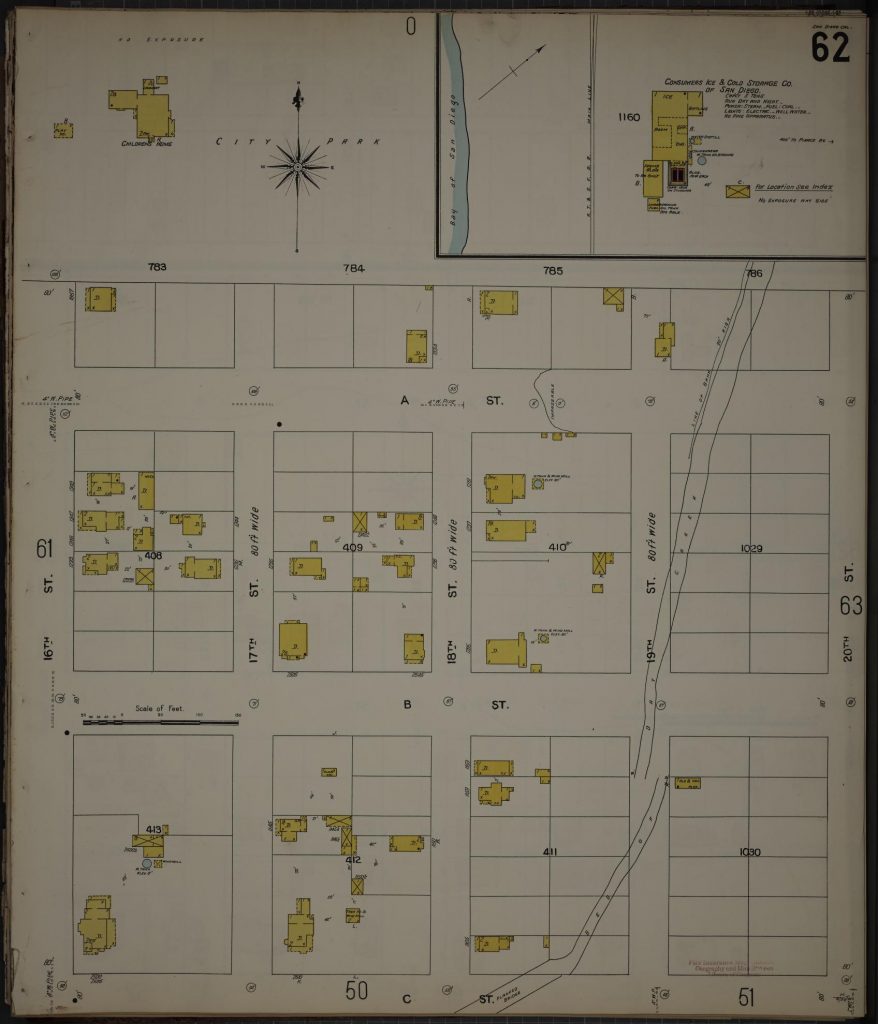

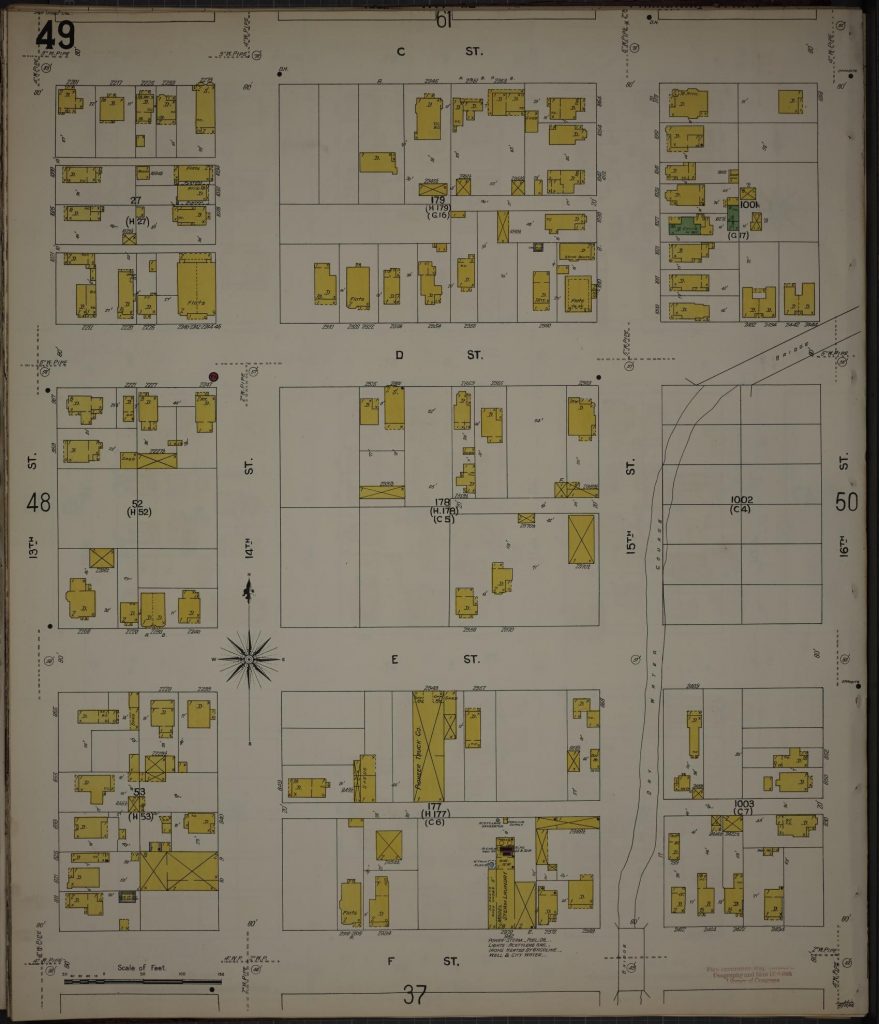

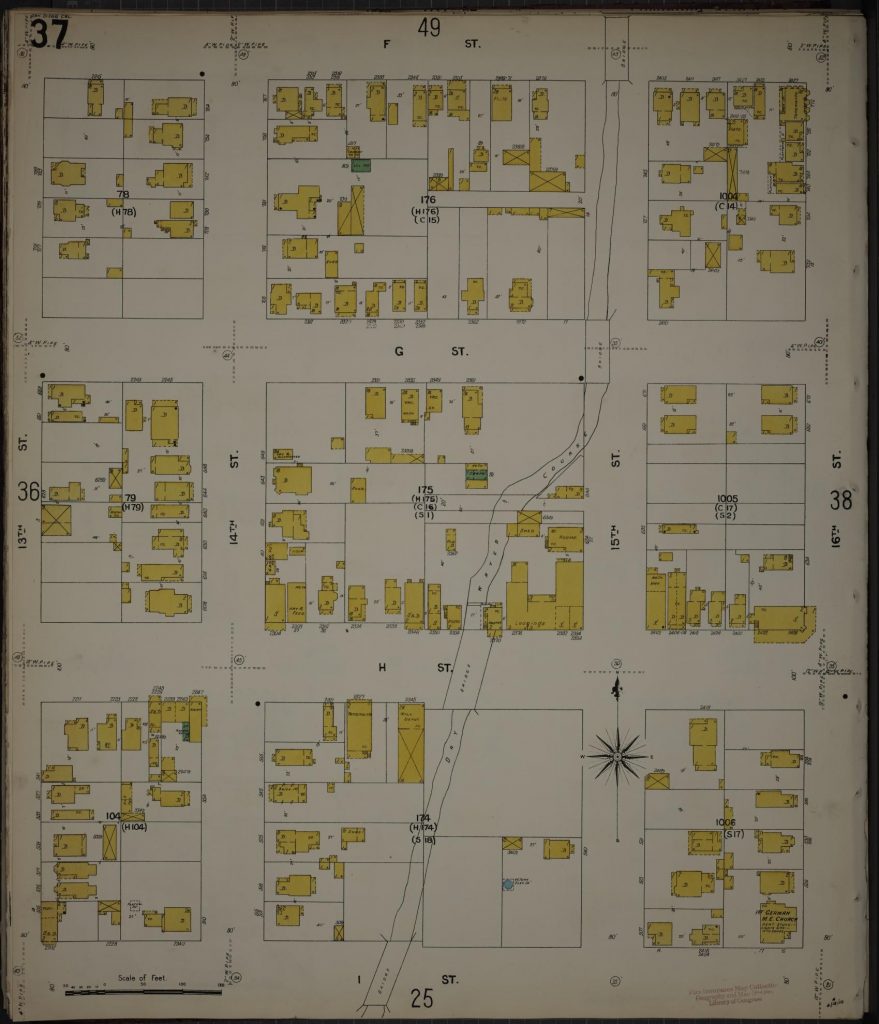

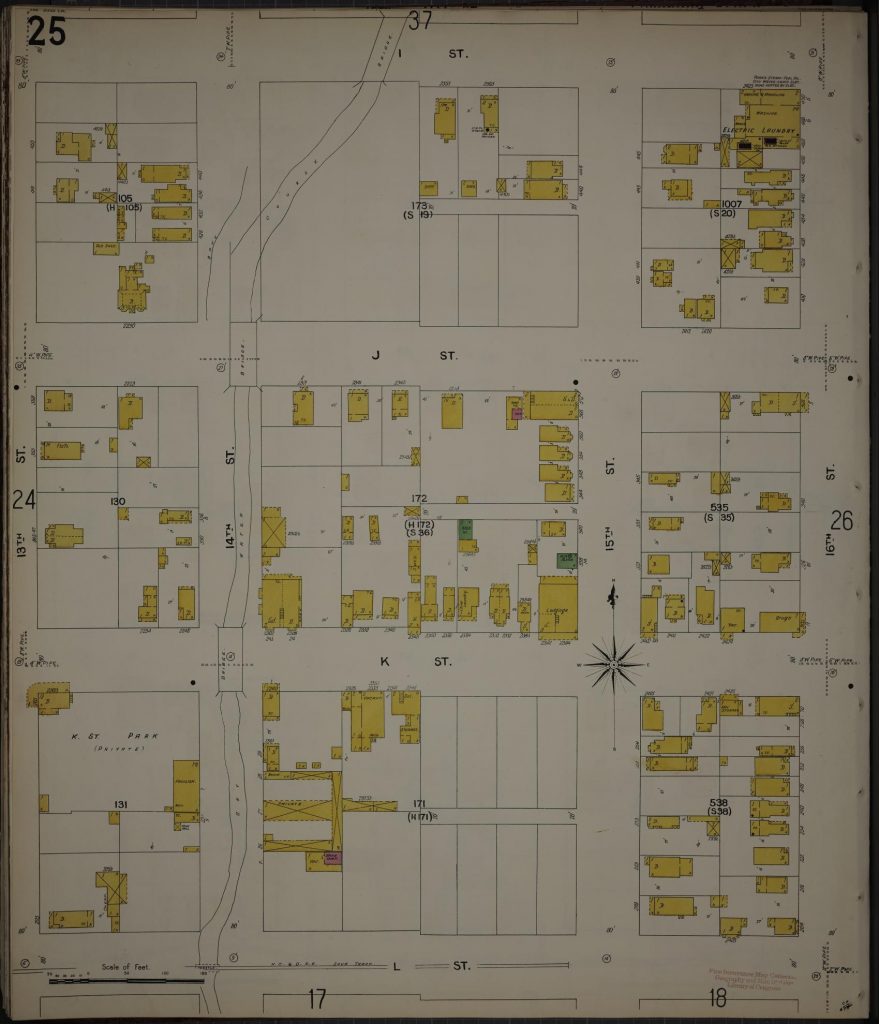

The story of Calvary Cemetery began in 1873 when the city purchased ten acres of land near Old Town from J. S. Mannasse ‘for Cemetery purposes’. In October 1873, after the City Attorney had prepared the necessary papers and the City Engineer had made a survey of the grounds and submitted a plat, the Board of Trustees adopted Charter Ordinance No. 46, ordaining that the real estate purchased by the city from J. S. Mannasse for cemetery purposes, containing ten acres, ‘is hereby set apart, dedicated, donated to and reserved as and for a Cemetery’. A second section of the ordinance specified that the west half of the property, containing five acres, ‘is hereby placed under the free and exclusive control of the Parish of the Immaculate Conception . . . to be held in trust and to be used and controlled exclusively by the parish forever, for Cemetery purposes only’. However, the land being found impractical for such purposes, in March 1876 the trustees repealed Ordinance No. 46 and adopted Charter Ordinance No. 78, exchanging the property for a different ten-acre tract owned by J. S. Mannasse after the Pastor of the Parish, A. D. Ubach, relinquished the church’s claim to the property. Ordinance No. 78 likewise set apart and reserved the ten-acre tract for a Cemetery and placed the western five acres under the control of the Parish forever for Cemetery purposes. Curiously, the Catholic cemetery, which became known as Calvary Cemetery, actually occupied the southern, not the western five acres of the cemetery tract; the northern five acres, shown on early maps as the Protestant Cemetery, was never used as a cemetery and was reclassified as a park in 1909.

Cave Johnson Couts attended United States Military Academy at West Point, class of 1843, where he was a classmate of Ulysses S. Grant, later Commanding General of the Union army during the Civil War and President of the United States. A cavalryman, Couts was posted to California in the aftermath of the Mexican War and met Ysidora Bandini, daughter of Don Juan Bandini, one of the most prominent residents of Alta California, while stationed at the San Luis Rey mission in 1849. According to California writer George Wharton James, Miss Bandini had visited the mission with some friends and while wandering around the building had fallen from a parapet. The young lieutenant, observant of the maid whose bright eyes had already penetrated his heart, dashed forward and caught her, averting a catastrophe. They then and there fell mutually in love and when they were married in 1851 she was given the Guajome rancho near San Luis Rey as a wedding present by her sister and brother-in-law. James claimed that Helen Hunt Jackson, author of the popular novel Ramona, spent time at Guajome and absorbed much of her understanding of life at a California rancho from what she observed there. Late in life Col. Couts converted to Catholicism, receiving his first communion shortly before he died in 1874. When Mrs. Bandidi de Couts died in 1897 the San Diego Union reported that the ‘lady of unusual intelligence and noble qualities’ would be buried beside her husband at the Catholic cemetery. However, since Col. Couts died in 1874 and the cemetery was not established at its present site until 1876, and its previous site had been found ‘impractical’, it is unclear how her husband came to be buried there.

Father Antonio D. Ubach’s burial in the Catholic cemetery, by contrast, was witnessed by thousands of mourners in what must have been the most notable day of its existence. Father Ubach was born in Catalonia and came to San Diego in 1866 where he took charge of what was then a small Catholic parish. He served as Pastor for 41 years and was greatly respected and admired, particularly by his Indian and Mexican parishioners. He is generally considered to have been the model for the Father Gaspara character in Ramona, and in later life confirmed that he did perform a marriage ceremony for an Indian couple much as described in the novel, although at his chapel, not in the building that has become known as Ramona’s Marriage Place. As Pastor of the Parish of the Immaculate Conception Father Ubach was given responsibility for the cemetery and is assumed to have supervised its planning and development. When he died in 1907 his funeral at St. Joseph’s Church was described as the largest ever held in San Diego, attracting an estimated four thousand people. After the service, the Union reported a line of carriages over a mile and a half long followed the hearse and that hundreds of poor Mexicans and Indians, who could not afford the luxury of riding, walked the four miles from the city to the Catholic cemetery.

In January 1919 a new Catholic cemetery, Holy Cross, was opened on Hilltop Drive, near Mount Hope Cemetery and Greenwood Memorial Park, and in 1920 the church ended the sale of plots in the old Catholic cemetery, although burials were still permitted in plots that had already been purchased. With few new burials and no budget for perpetual care, the old cemetery, which began to be referred as Calvary Cemetery, soon begin to show signs of neglect. In 1935 Albert Mayrhofer, president of the California State Historical Association, presented plans to the City Engineer for improving Calvary Cemetery. Mayrhofer had been instrumental in the restoration of Mission San Diego in 1930-31, for which he and his wife had been dubbed Sir Albert and Lady Marie, Knight Commander and Lady of the Holy Sepulcher, by Pope Pius XI (he also designed the San Diego flag, still in use today). The plan for Calvary Cemetery was to build an adobe wall with gates around the cemetery to deter trespassing and vandalism.

Sir Mayrhofer had secured funding for the adobe wall as a Works Progress Administration project and the WPA required that the city take ownership of the site and agree to sponsor the project. Work on the wall began in November 1938 and was completed in October 1939. A rededication ceremony was held in November 1939 with religious services and a civic program, after which Mayrhofer presented the key to the gates to Bishop Buddy and the bishop unveiled a large granite boulder on which the names of those who contributed to the restoration of the cemetery were carved. While the city retained ownership of the cemetery, the expectation was that it would be maintained by the church.

Even though Calvary Cemetery was virtually abandoned after 1920, some San Diego pioneers still chose to be buried in family plots located there. The San Diego Union reported in 1936 that by special arrangement, the body of Mrs. Ester Smith Kerren would be buried in her ‘ashes-of-roses’ wedding dress beside her husband at Calvary Cemetery, in a plot given to her by Fr. Antonio D. Ubach. She was a San Diego resident since her birth in 1853, daughter of Albert B. Smith and Maria Guadalupe Machado. She sang in the first choir that Fr. Ubach organized in the adobe chapel in Old Town. Her father had become famous when he spiked two Mexican cannons and climbed a flagpole in Old Town to attach an American flag in October 1846.

Cave Couts II, considered the last of the San Diego Dons, died in 1943. According to the Union, ‘In the old Catholic cemetery, rarely used any more and only recently rescued from years of neglect and vandalism, the old don was buried beside the almost legendary first Cave Couts and his beautiful Ysidora’. In 1949 Lily Bell Schrader, his first wife, was also buried at Calvary Cemetery. Altogether 46 burials were recorded in the cemetery after 1920, the last occurring in 1960.

Also in 1949, the San Diego Union noted the continuing deterioration of Calvary Cemetery under the headline Broken Monuments, Maimed Statues Desecrate Sleeping City of Dead. ‘Desolation broods uneasily over historic Calvary Cemetery in Mission Hills’, the Union story began. ‘Headstones have been broken and overturned; rusted metal railings, which once protected burial plots of distinguished citizens, have been twisted, torn away and looted’. Perhaps most dramatic was a photo of the stone cross marking the grave of Father Antonio Ubach, who the article described as the founder of Calvary Cemetery, and the adjoining grave of Albert Mayrhofer, for whom there was no marker of any kind. The Union explained that Mr. Mayrhofer had been deeply interested in Calvary Cemetery and worked tirelessly to resist its growing neglect, but although he had died 10 months earlier his grave was without a marker and a visitor would be able to find the spot only through instructions from Mrs. Mayrhofer. She had been so disturbed by the evidences of vandalism and lack of care and protection for the cemetery that she had been unwilling to risk setting up the kind of memorial she would want (a marker was eventually erected over Sir Mayrhofer’s grave, and as Lady Mayrhofer had anticipated, it had been vandalized, but she had not anticipated that by the time of her death in 1993 she could not be buried next to her husband under the marker that already bore both of their names).

Other photos in the 1949 Union story showed a ‘wooden cross torn from its grave by vandals’, ‘solid granite headstones torn from their bases and flung sprawling on graves’, ‘stone monuments which had developed a list by reason of the ground underneath settling’ and an ‘old grave in a sad state of dilapidation brought about by repeated, prankish acts of desecration’.

Not much had changed by 1962 when the Union again reported on Calvary Cemetery: Where History Lies Abandoned. This article noted that since the 1939 restoration there had been no full-time caretaker and left unguarded the burial ground had become a rendezvous and playground for vandals with graves desecrated and headstones toppled, broken and carried away. However, a recent state law gave the city authority to convert abandoned cemeteries into memorial parks, and this was being considered by the Park and Recreation Department. Some relatives of those buried in the tract said they would prefer a well-grassed park properly marked with a monument to the present condition.

With no caretaker and no perpetual care funding, maintenance was left to community service groups. In 1963 and 1964 a Boy Scout Explorer post spent weekends cleaning up trash and debris and straightening and resetting toppled headstones. However, most community interest in Calvary Cemetery had turned to the proposal to convert it into a ‘pioneer park’. A letter to the editor of the San Diego Union in 1967 noted that funds for the Calvary Cemetery project had been approved in a park bond election the previous year but that development was tentatively scheduled for 1971-72 and that was too long to wait; ‘Calvary Cemetery, the target of vandals and the scene of nightly beer parties, is an unwholesome situation to be left so long’. Also in 1967, Hillcrest and Mission Hills residents told the Union that Calvary Cemetery was dangerous and a neighborhood eyesore. It had been run down for years and was a disgrace to the neighborhood and the city. It was filled with weeds, bottles and tipped-over headstones and ‘ghosts would be afraid to go in there at night’. They also asked for more police patrols and more cleanup work.

In 1968 the city initiated the legal process of transforming the cemetery into a memorial park by passing a resolution that whereas Calvary Cemetery was a nonendowment care cemetery, and that no human dead bodies had been interred for at least five years, and that the cemetery and all its ‘copings, improvements and embellishments’ were a threat and danger to the health, safety, comfort and welfare of the public, that the cemetery ‘is hereby abandoned’. The City Manager was directed to remove all the copings, improvements and embellishments. The resolution was unopposed.

An architectural firm hired by the city for design work proposed grouping the individual monuments together as one large memorial. An alternate plan proposed moving all the monuments to the city’s Mount Hope Cemetery and building a large central memorial. Some descendants of the pioneers expressed opposition to any plan that would disturb the monuments marking the graves of their ancestors. Descendants of the Pedrorena and Altamirano families wrote city officials to say that while they were not opposed to the idea of a park, they thought their ancestors’ monument should be left intact as part of a central memorial. These wishes were disregarded, and the contract for converting the old Calvary Cemetery into a pioneer memorial park awarded in February 1970 required that the headstones be moved. According to the City Manager, some would be relocated in the park but the others would be stored at Mount Hope. A group of Mission Hills residents had agreed to work with the city to select headstones of historical significance that would be retained in the park.

However, when the Mission Hills – Hillcrest Improvement Association selected 600 headstones to be retained for their historical importance, other Mission Hills residents protested. In May 1970, the day after workmen had started the improvement project, placard-bearing demonstrators, including children carrying signs reading ‘Creepy’ and ‘Spooky’, picketed the site to demand the removal of all the tombstones. Work was resumed after the two sides met with city officials and agreed to a compromise in which 142 of the most historically important stones would be retained, clustered in the south-east area of the park. The anti-stone group’s agreement was halfhearted; according to their spokesman, Albert A. Gabbs, the concept of a park would be utterly destroyed by the somber sight of a graveyard superimposed upon the landscape. The tombstones would present a ‘morbid attraction’ to the ‘sick, witchcraft and spook-oriented element of our society’. Parents would think twice about allowing their children to visit the park and the elderly and retired who live nearby would find the markers a ‘constant reminder of the grim reaper’. The improvement association spokesman, however, noted that the markers are ‘part of our history and our heritage’ and the park is a ‘historically interesting site’. The improvement association also turned over the records and materials they had accumulated and photos of the headstones to the San Diego Historical Society.

Landscaping was finished and Pioneer Park was opened to the public in April 1971, although not officially dedicated until December 1977, but the controversy over the tombstones continued. In July 1977 the Union had published photos of 7- and 8-year old brothers playing on the relocated monuments at the edge of the park, one stepping from one former grave stone to another and the other sitting on top of a grave stone inscribed with the name of Nellie Grace Dorval, a child who died in 1918. This prompted an angry letter to the editor from a reader who had known Miss Dorval and still remembered her suffering and death, calling the photos sacrilegious and disrespectful and wondering why parents would allow children to jump on the grave stones (an editor’s note clarified that these were not technically grave stones, having been removed from their original sites over graves years previously and lined up along one side of the park). Albert A. Gabbs took the opportunity to again warn of the attraction the former tombstones presented for those interested in the macabre, claiming that the area was littered with ‘things better not described left over from unusual gatherings which take place during the night’, and all because the Park and Recreation Board appeased the Historical Society by allowing the tombstones to remain.

In 1983 the San Diego Union published an article about a ‘graveyard of tombstones’ dumped near a railroad track in Mount Hope Cemetery (by one account the tombstones had been noticed by then-mayor Roger Hedgecock while inspecting the proposed route of the East Line of the San Diego Trolley, which would eventually operate over that track). These were some of the 400-500 tombstones from Calvary Cemetery which had been sent to Mount Hope, and the Union reported that although they had been put in a small canyon for ‘indefinite storage’, many of the ‘chipped and battered grave markers’ were covered in weeds and dirt and gradually disappearing into the undergrowth while their importance faded from memory. The Evening Tribune followed up with a report in July 1985 that there were 288 cracked or shattered gravestones haphazardly strewn near the proposed route of the East County extension of the San Diego Trolley.

The rediscovery of the discarded tombstones at Mount Hope and their undignified treatment there revived the debate about their proper disposition. The San Diego Historical Society asked that the gravestones be stored in a dignified manner or moved, but the City Manager’s office recommended that the area in which the gravestones were piled be fenced off for five years to allow the stones to be claimed by descendants of the deceased, or otherwise disposed of. The city Historical Site Board, an advisory board to the city council, voted unanimously not to support the City Manager’s plan and expressed support for relocating them back to Pioneer Park. The directors of the Save Our Heritage Organization also voted unanimously in favor of moving the gravestones back to Pioneer Park, where ‘at least they’ll be in the right cemetery’. The National Society of Colonial Dames of America pledged to contribute $500 toward placement of the stones, saying ‘the stones belong with the bones’.

In January 1986 the matter came to the attention of the city council where ‘shocked’ members of the Public Facilities and Recreation Committee voted unanimously to restore the tombstones and move them back to the Mission Hills site; the tombstones ‘had been given no more respect than discarded beer cans . . . this is really quite shameful’. However, despite the committee’s vote, the move never happened. The tombstones taken to Mount Hope in 1970 remain there, although they are no longer strewn haphazardly along the trolley tracks. Most were buried in a ‘mass grave of gravestones’ while a group of about twenty stand beside the tracks on a concrete base, much like the 142 that remained at what was once Calvary Cemetery, where so many of the pioneers who helped to found and build San Diego are still buried under the eucalyptus trees.