On January 16, 1908, the 1:55 PM train with 30 passengers bound for Pacific Beach and La Jolla departed from the Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railway station at the foot of C Street in San Diego. According to the San Diego Union, the train was steaming through Middletown at a fair rate of speed when it left the rails and plowed along the ties for fully 300 feet before the engine turned over on its side at right angles to the track. The engineer, Thomas Robertson, was pinned in the engine’s cab by the reverse lever and scalded to death by steam escaping from the boiler. The fireman, Thomas Fitzgerald, was hurled head foremost into a clump of cactus and also badly burned by escaping steam (he died of his injuries 10 days later). Although women screamed and men made for the doors, the two coaches and mixed coach/baggage car making up the train remained upright and came to a standstill amid the hiss of the steam. Not a passenger was even so much as scratched nor was there a window in either of the three cars broken; the fright incident to the cars bumping along over the ties and a severe shaking up summed up the damage to the passengers.

The Union interviewed one passenger, Miss Zoe Overshiner, a 16-year-old girl from Pacific Beach who was on a front seat of the first car and ‘tells a graphic story of the accident’:

I was talking with [a] friend of mine about something, I’ve forgotten what it was now, when all of a sudden the engine began to act funny and our car began bumping heavily. This was due, as we afterwards found out to the fact that it had left the rails. The first shock was not so bad as might have been expected and we were not frightened until we saw the engine plunge over the bank and turn over on its side. Then the steam hid the engine and I climbed through the window of the car and jumped to the ground. I didn’t want to get hurt and the door wouldn’t open, or at least, I though it wouldn’t. I don’t remember whether I screamed. Maybe I did. It was enough to make any one scream when the engine reared up in the air and turned over on its side. It’s no joke to be in a railroad wreck.

The writer added that ‘it is probable that she is right’.

The 1908 train wreck occurred where Winder Street then crossed the railroad right-of-way, near where West Washington Street passes under I-5 today. The immediate cause was said to have been ‘spreading of the rails’; spikes holding one of the rails to the ties had come loose, the rail had shifted and the engine had fallen through and bumped along on the ties. The railroad company admitted that while much of the line had recently been improved with heavier 60-pound rails, the work of relaying the track had stopped short of the site of the accident, where the rails were of the lighter 35-pound type first used on the line and in service ever since. However, the company claimed that the track where the wreck occurred had been put in good shape two or three days before.

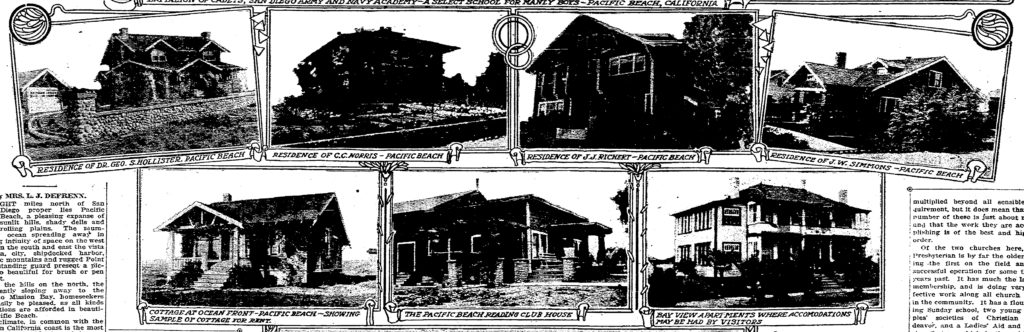

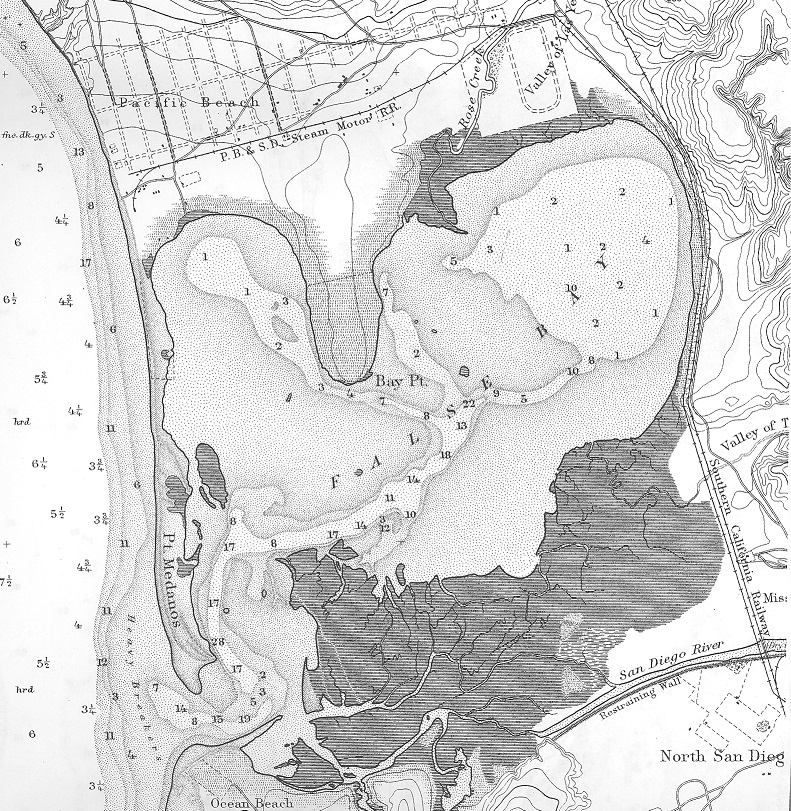

Like Miss Overshiner, most of the passengers who had been scared and severely shaken up in the accident were residents of Pacific Beach or La Jolla, and the two victims were also long-time local residents. Thomas Fitzgerald had worked for what was then the San Diego, Old Town and Pacific Beach Railway when it was first completed to the foot of Grand Avenue in 1888, and he had built a house on Reed Avenue near the depot there. Thomas Robertson’s family had once lived in the Pacific Beach Hotel building near the depot and Mrs. Robertson was a charter member of the Pacific Beach Reading Club. When the railroad was extended to La Jolla in 1894, becoming the San Diego, Pacific Beach and La Jolla Railway, these railway employees had moved to its new base there, where the Robertsons’ home was noted for its rose garden (although the company’s name was changed again in 1906, suggesting a move even further up the coast, the tracks were never extended beyond La Jolla).

Understandably, a fatal train wreck involving a number of their fellow citizens and raising doubts about the safety of their only transportation link to the city caused concern, and sparked anger and outrage, in the affected communities. On January 27, eleven days after the accident, the Union reported that 25 or 30 people attended a hearing before the city council of a petition signed by nearly 200 citizens of Pacific Beach, La Jolla and other points along the line of the LA&SDB asking for an investigation (at the time there were only about 300 households in Pacific Beach and La Jolla combined):

We the undersigned, citizens of Old Town and patrons of the Los Angeles & San Diego Beach railway, most respectfully request that your honorable body fully investigate the conditions and methods of said railroad. That all laws and ordinances of every kind regulating said railroad be vigorously enforced, so that not only our rights as citizens be secured, our comforts and conveniences be regarded, but our lives and those of our families be made reasonably secure when forced to use said railroad. We would call your attention to the following notorious facts:

First. This road is and has been for some time in a frightfully dangerous condition, many of the ties being rotten and the spikes in such a state that they can be extracted with the fingers. Even the new parts of the road being, in the opinion of those competent to judge, badly constructed. The engines and cars are very old, small, out of date and without the safety equipment the law requires, all this making travel perilous to the last degree, so much so that the late sad accident, long predicted, might have been a frightful calamity.

Second. The convenience or wishes of the citizens are in no way considered as to train service or the time table. The trains are too few in number and are run at inconvenient hours.

Only a part of the abuses have been stated, but we pray your honorable body that steps be taken by you to secure our rights and restore our comforts and safety.

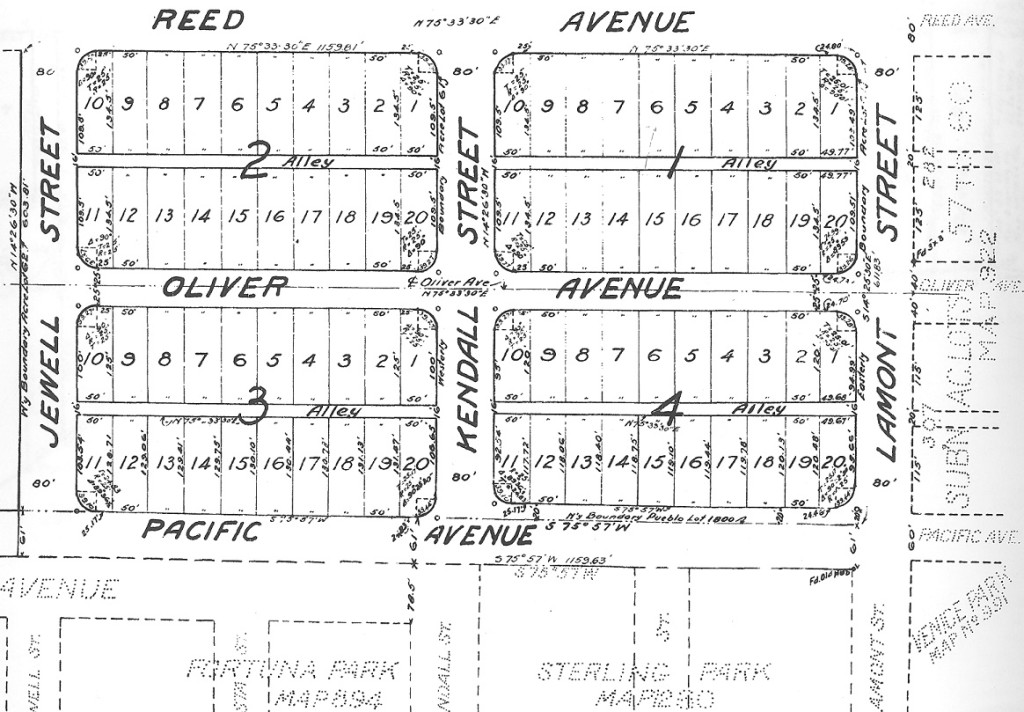

At the council meeting, which was also attended by General Manager Hornbeck and Attorney Leovy representing the railroad company, a Mr. Dyer, said to have lately located at Pacific Beach, stated that every statement made in the petition was true (there is no contemporary record of a Mr. Dyer in Pacific Beach; possibly the speaker was Mr. De Hart, who had recently moved to a home on Shasta Street). He said that with reasonably safe and proper railway service many hundreds would be added to the population of Pacific Beach but as it was, every time people boarded the trains they did so with fear and trembling. Mr. Rockwood (of The Rockwood, PB’s first apartment building, at Bayard Street and Thomas Avenue, a block from the railroad’s Ocean Front station on Grand at Bayard) described how he had found a broken rail just the day before the accident and had flagged down a train with a red bandana, possibly preventing another accident. He also explained how it was possible to pull spikes from the ties with the fingers and that dozens of the ties were rotten. A. C. Pike (presumably W. A. Pike, who owned most of the two blocks north of the railroad’s Grand Avenue right-of-way, adjacent to its Pacific Beach station at Lamont Street) stated that he had actually counted 702 rotten ties, that many spikes were not properly driven and many of the rails were rusty, being, in fact, crystalized with it. He closed his remarks with the ‘somewhat abrupt conclusion’ that the whole road was rotten, equipment, roadbed, even the official management. A. S. Lane (whose home on Hornblend, now the Baldwin Academy, was a block from the Pacific Beach station) asked that a committee be appointed to go over the railroad, although he noted that considerable improvement work had been done since the recent accident.

General Manager Hornbeck replied to the criticisms at considerable length, beginning by complaining that the petition had been prompted by the spirit expressed by Mr. Pike, that the official management of the railroad was ‘rotten’. He dismissed criticism of the ties, saying that the new, heavier rails were laid on the same class of ties and would have been laid on the existing ties at the scene of the accident except for construction delays. When a protester interrupted Mr. Hornbeck to ask why the railroad had been in such a hurry to burn the ties damaged by the train leaving the track, Mr. Hornbeck replied that this was a dirty, contemptuous story; he agreed that the ties had been burned but that it was 24 hours after the accident, they were worthless and they were burned to get them out of the way. When Mr. Hornbeck alleged that unfair means had been used to secure signatures for the petition and some had signed without knowing what they were signing, one of the petitioners ‘came to his feet in a hurry’ and declared that Mr. Hornbeck’s statement was a lie. The president of the council attempted to restore order, saying that personalities must not enter into the discussion – to which the petitioner replied that Mr. Hornbeck had started it. Mr. Hornbeck did agree to the suggestion of a first-hand inspection and invited every member of the council to go over the railroad and see for themselves. After further discussion it was decided to make the trip the following week.

Eight out of the nine members of the city council accompanied by City Engineer Crowell, General Manager Hornbeck and a number of the petitioners, made the inspection trip in a special train. To make the examination thorough, the councilmen walked much of the way from the city to the ‘Scripps station beyond Pacific Beach’, presumably referring to the Ocean Front station on Grand at Bayard Street, the palm-lined drive leading to F. T. Scripps’ bayfront mansion (where the Catamaran Hotel now stands). From Pacific Beach to La Jolla, which would have followed a route along today’s Mission Boulevard, La Jolla Hermosa and Electric avenues, and Cuvier Street, the party inspected the roadbed from an open flat car. According to a report in the San Diego Union the following day, the eight council members were expected to report that the statements in the petition were much exaggerated and that the line was reasonably safe for travel, probably as much so as any of the railroads running out of the city. ‘After the representations made by the petitioners I was surprised to find things in as good shape as they are’, said one councilman.

The ninth council member, F. J. Goldkamp, dissented from the general consensus of his colleagues. He had made a personal inspection trip over the railroad before the official inspection because, he said, a petition signed by 200 people, 20 of whom had appeared before the council, was a matter that should not have been delayed for 10 or 12 days and that in the meantime the company had a chance to make improvements of the existing conditions. For example, he reported that he saw a worker being employed driving spikes into the ties. Mr. Goldkamp contended that the complaints of the people were fully borne out by the conditions as he found them, and he had personally pulled spikes out of the ties with his fingers.

The two reports resulting from the separate inspections of the LA&SDB were presented to the city council at a meeting on February 18, 1908. According to the San Diego Union, the report by City Engineer Crowell ‘practically exonerated’ the company from the charges made by citizens of Pacific Beach and La Jolla and concluded that the roadbed was perfectly safe for public travel. Mr. Crowell’s report stated that the roadbed from the downtown station to a point past Winder Street in Middletown was in fine condition, having been recently relaid with new 60-pound steel rails and the grades much improved by cutting down the hills and filling in the low points besides straightening the line and eliminating two bad curves. From the end of the new track to Old Town the track had the old light rails and there were many bad ties, although they were no worse than was found on any other railroad leading out of the city.

Through Old Town the track had been straightened out and entirely reconstructed with new ties and 60-pound rails. The bridge over the San Diego River was in good condition except for some bolts that needed to be tightened. ‘In one or two instances’ he found a tie in a condition that would allow pulling a spike out with the fingers, a condition which also applied to the parallel Santa Fe (a mainline railroad with much more traffic carrying much heavier loads).

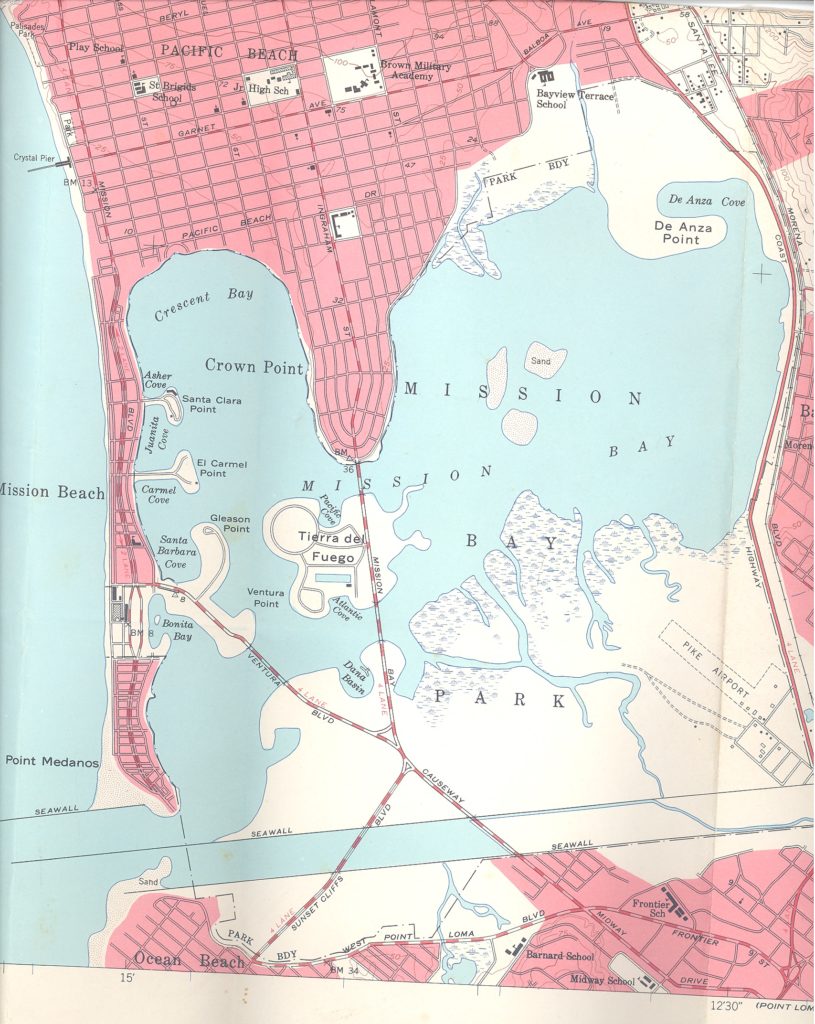

From Old Town to Pacific Beach the roadbed had been widened and a cut-off built across the race track, eliminating a number of curves (this cut-off replaced the circuitous route around the former race track east of Rose Creek via what are now Mission Bay Drive and Garnet and Balboa avenues to Lamont Street with the more direct route along present-day Grand Avenue to Lamont). He walked over a good portion the track from the Pacific Beach station (Lamont Street) toward the ocean front and found that portion in good condition. ‘After going over the whole length of the road, I have no hesitancy in saying that I do not consider the roadbed in a dangerous condition’. Mr. Crowell’s report was referred to the city attorney.

Councilman Goldkamp’s report stated that the complaints of the people were fully borne out by the condition of the road at the time of presenting their petition. Owing to the lapse of ten days between presenting the petition and the inspection the railroad people were enabled to employ a large staff of extra men to repair all the worst parts of the road, to replace broken ties, to drive in loose spikes, to put in new ones and cover up all the defects sufficiently to pass the investigation of the councilmen. Mr. Goldkamp contended that this work of making the road appear safer at the time was only of a temporary nature and owing to the rottenness of the ties and the lightness of the rails these parts were liable to become unsafe again very soon. The rolling stock was old and out of date and made more unsafe by the use of old-fashioned link and pin couplings connecting the cars. He concluded that in view of the growing population of Pacific Beach and La Jolla it was time for the service to be modernized. The owners had apparently expressed a desire to ‘electrize’ the line and the council should call upon them to complete that process within six months or their franchise should be forfeited. Mr. Goldkamp’s report was simply filed.

Although the LA&SDB was never ‘electrized’, it did upgrade its rolling stock in the next few months with a pair of new gasoline-powered McKeen rail cars that had the added advantage of being able to operate over the city’s street railways and convey suburban passengers to and from businesses and theaters near the center of town without changing trains (steam trains were not allowed on downtown streets and could only go as far as the line’s terminus at the foot of C Street). The McKeen cars were painted a ‘rich Tuscan red’ and soon became known as ‘Red Devils’. And despite Mr. Goldkamp’s misgivings, the rottenness of the ties and the lightness of the rails did not contribute to any further accidents on the La Jolla line, although about 20 passengers were injured, one seriously, when a La Jolla train collided with a Santa Fe train in 1917 at a crossing near Old Town. The railroad was also involved in accidents with automobiles, including one in which a woman was killed and several other passengers seriously injured when it collided with a La Jolla train in Old Town in 1909.

Automobiles were first introduced to San Diego in 1900 and as their use increased over time, and roads to Pacific Beach and La Jolla were improved, fewer residents were ‘forced’ to use the train to reach destinations downtown. With fewer passengers to pay operating costs, the Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railway applied to the Public Utilities Commission to discontinue service and in 1919 the line was abandoned. The rails were torn up and sold for scrap, although the section of right-of-way between Grand Avenue and Bird Rock over what are now Mission Boulevard and La Jolla Hermosa Avenue was reused between 1924 and 1940 for an electric railway line from downtown to La Jolla via Mission Beach. North coast residents forced to use that line were still not entirely secure, however. In 1937 a pair of the electric cars collided head-on in heavy fog in the Midway area, injuring 31 passengers, some seriously.