Venice Park is a subdivision in the southeastern portion of Pacific Beach, extending east from Lamont Street and south from Pacific Beach Drive to the marshland around the shore of Mission Bay. The area was once part of the Pacific Beach subdivision, which, south of Reed Avenue, had been divided into ‘acre lots’ of about 10 – 15 acres. Acre lots 72 and 73 were south of what became Pacific Beach Drive, with lot 72 between Lamont and Morrell streets and lot 73 between Morrell and Noyes. These two lots had never been sold to private buyers and when the Pacific Beach Company was dissolved in 1898 and its unsold properties distributed to shareholders they were among the properties that went to one of the largest, the First National Bank of San Diego. In March 1906 the bank sold acre lots 72 and 73 to Abstract Title and Trust, which then granted them to E. H. Hinkle, a principal of the Kirby-Hinkle Realty Company, and F. E. Patterson, a purveyor of photo supplies. Hinkle and Patterson drew up a subdivision map of ‘Venice Park, being a portion of lots 72 and 73 Pacific Beach’ and the map was approved by the San Diego city council in April 1906.

The map of Venice Park extended the streets of the Fortuna Park addition to its west, with Mission View Boulevard along the shoreline intersected by the east-west Pacific, Sunset and Roosevelt avenues (although Roosevelt Avenue remains, the other streets are now called Crown Point Drive, Pacific Beach Drive and Fortuna Avenue). ‘Morell’, the extension of Morrell Street in Pacific Beach, and a new street, Honeycutt Street, ran north and south between Pacific and Mission View and intersected Sunset (Honeycutt was named after a prominent local resident, Sterling Honeycutt; the misspelling of Morrell was officially corrected in 1935). Venice Park met Fortuna Park along a widened Lamont Street and like Fortuna Park, but unlike most of Pacific Beach, Venice Park lots faced the north-south streets – Lamont, Honeycutt, Morrell, and the shoreline boulevard.

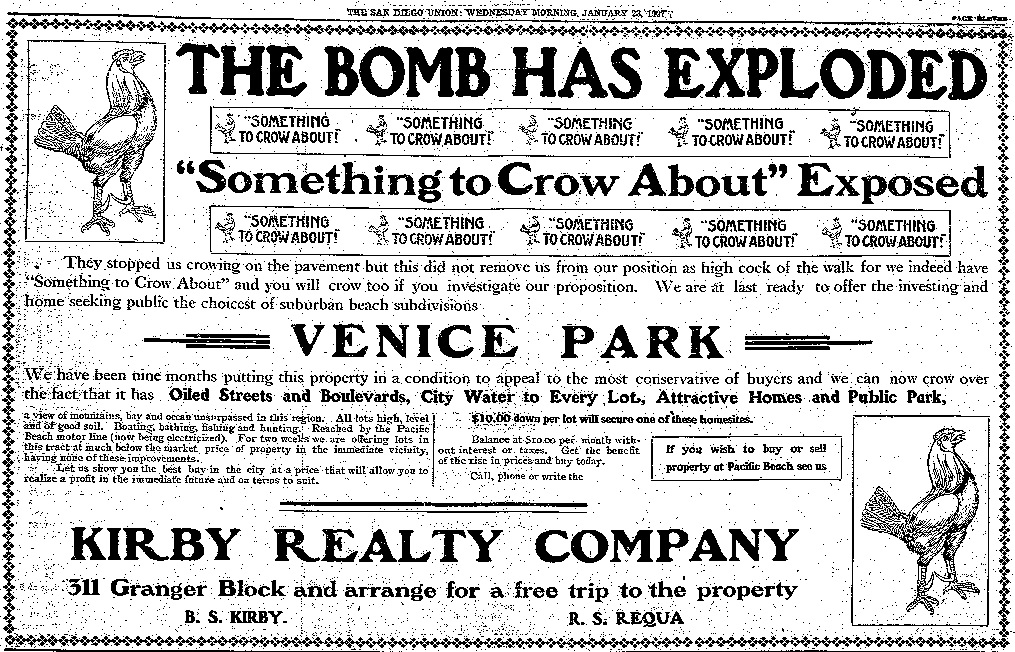

E. H. Hinkle left Kirby-Hinkle Realty shortly after the approval of the Venice Park map but development of the subdivision continued under his former partner Bert Kirby. In September 1906 a building permit was issued to Kirby Realty for a dwelling in Venice Park valued at $2000 and in October Kirby Realty received a permit for a cottage on lots 41-42, block 1, Venice Park, valued at $1800. In addition to building the two houses, Kirby Realty had spent much of 1906 on other improvements to Venice Park. An ad in the San Diego Union in January 1907 stated that they had been nine months putting the property in a condition to appeal to the ‘most conservative of buyers’ and now had ‘something to crow about’; oiled streets and boulevards, city water to every lot, attractive homes and a public park. The lots were high, level and of good soil, and had an unsurpassed view of mountains, bay and ocean, according to the ad. This choicest of suburban beach subdivisions was reached by the Pacific Beach motor line (‘now being electricized’), and featured boating, bathing, fishing and hunting. $10 down would secure one of these homesites with the balance at $10 per month without interest or taxes (in early 1907 the Los Angeles & San Diego Beach Railroad, which ran through Pacific Beach, was being realigned to run over what is now Grand Avenue instead of Balboa Avenue east of Lamont Street, but it was never converted to electricity). Kirby Realty also produced an illustrated brochure featuring Venice Park, ‘the ideal home spot’.

Kirby Realty ads for Venice Park in 1907 were attributed to B. S. Kirby and R. S. Requa, who were not only business associates but also members of San Diego Lodge No. 18 of the Fraternal Brotherhood. The Evening Tribune described one ‘delightful social’ given for members and friends of the brotherhood in September 1906 where one of the ‘friends’, Miss Viola Hust, played the piano and Mr. Kirby performed two ‘illustrated songs’, the slides for which were colored by Richard S. Requa and were very beautiful indeed, including scenes in and about San Diego. In February 1907 the papers reported that Miss Hust had married Mr. Requa, a member of Kirby Realty. The happy couple had left on the noon train for a brief honeymoon in the north and would be ‘at home’ to their many friends and acquaintances after March 15 at Venice Park, Pacific Beach (presumably in one of the two existing homes there, built by Kirby Realty).

Richard Requa did not remain a member of Kirby Realty for long, however. By 1908 he was working with the prominent architect Irving J. Gill and in 1910 a special notice appeared in the Union announcing the dissolution of the partnership which heretofore had existed between Gill and Requa. Mr. Requa would open offices in the McNeece Block, as the Keating Building at the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue and F Street was then called. Irving Gill and Richard Requa both went on to become important figures in San Diego architecture during the early 20th century. Requa was notable for the Spanish Revival designs that characterized communities like Kensington Heights.

In Venice Park, the Kirby Realty sales campaign initially had a positive effect and 101 lots had been sold (out of a total of 224) and a total of 5 houses built by the end of 1907. By 1911 all but 16 lots had been sold, but most buyers apparently purchased the lots as investments and only two more homes had been constructed. Most of the homes were in block 1, perhaps because it was closest to the train station and stores at Lamont Street and Grand Avenue, four blocks away. There was one home at the northern end of block 2 and one a block further south on block 4, but no homes had been built on block 3 or on blocks 5 through 8. The number of homes in Venice Park actually decreased that year when, according to the Pacific Beach Notes column in the Evening Tribune, the total destruction of the home of H. A. Collins by fire again demonstrated the need for fire protection in this part of the city. A committee of the Pacific Beach Progressive Club would again try to induce the city fathers to give the needed fire and police protection (a fire station was not built in Pacific Beach until 1934).

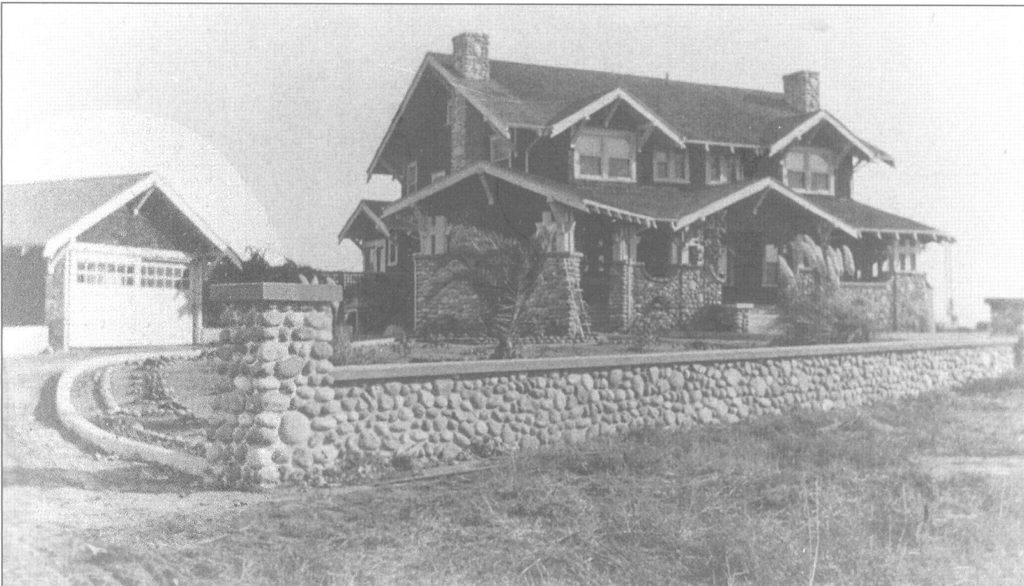

In 1913 Dr. George S. Hollister purchased the five lots in block 7 of Venice Park and in October he received a building permit for an 11-room, two-story frame residence valued at $7500 on Mission View Drive. The builder was D. L. Furry, who was married to Dr. Hollister’s sister and who also lived in Venice Park, on Honeycutt Street. The home built for Dr. Hollister, on a point east of the bayside boulevard overlooking Mission Bay, was for many years the crown jewel of Venice Park and one of the showplace homes around Pacific Beach. In 1919 Dr. Hollister also purchased E. H. Hinkle’s undivided half (actually .5854) of the portions of acre lots 72 and 73 that had not been included in the Venice Park subdivision, marshland that surrounded his home to the east and south.

The home and property on block 7 and Dr. Hollister’s share of the surrounding marshland were sold in 1923 to Robert and Mary Harris. ‘Bob’ Harris was described as a former horseman and well-known sportsman, a familiar figure at racing and boxing events in Tijuana (a horse that ran at the Aqua Caliente track in the 1920s was named Bob Harris in his honor). Mrs. Harris was a former star on the Orpheum vaudeville circuit whose stage name had been Lotta Gladstone. However, in August 1926 the Union reported that Bob Harris, retired capitalist and former race horse owner and trainer, had disposed of his Pacific Beach manor and moved back to town (in 1931 it reported that two bodies found in a wrecked car at the bottom of a deep canyon off the Torrey Pines grade had been identified as Mr. and Mrs. Robert Harris, a widely known race horse owner better known as ‘Bob’ and the once-famous Lotta Gladstone).

The buyers of the Harris manor in 1926 were Dr. Oscar J. Kendall and his wife Lena. A few months later, in March 1927, F. E. Patterson, who still retained his .4166 share of the portions of acre lots 72 and 73 not included in Venice Park, agreed to remise, release and quitclaim to the Kendalls his right, title and interest in acre lot 73, giving them full control of that portion of the marshland behind their home. In exchange, the Kendalls quitclaimed to Patterson all their right, title and interest in acre lot 72. Later in 1927, after the death of their 17-year-old son Billie, the Kendalls moved back to their old San Diego residence on First Street and donated the use of their Pacific Beach home to the Talent Workers, a charitable organization that Mrs. Kendall had co-founded in 1910. The home would be known as Bill Kendall’s House and would be headquarters for a new division of the Talent Workers to be called the Bill Kendall Division. Before the Kendalls returned to Venice Park in 1931 their house there was used for bridge parties and other events to benefit worthy organizations like the Talent Workers and the Pacific Beach Woman’s Club. Dr. Kendall died in 1936 but Lena Kendall continued living in the bayfront home into the 1960s. In 1951 she donated her property in acre lot 73, except for the area immediately surrounding her home, to the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. This section of acre lot 73 and most of the adjoining acre lot 74, donated by the Frost family, is now preserved as the Kendall-Frost Mission Bay Marsh Reserve.

Little additional development had occurred in Venice Park in the years after construction of the bayfront home in 1913. In 1920 John Garino, a downtown café owner, acquired the 12 lots at the northeast corner of block 1, which also included one of the two original cottages built by Kirby Realty in 1906. His developments were primarily agricultural and when he placed it on the market in 1923 the ad described a modern 6-room house, garage, 100-foot chicken house, 60 fruit trees and 200 grape vines, for only $4500. The house, possibly the one where Richard and Viola Requa were ‘at home’ to their friends in 1907 and likely designed by Requa while he worked with Kirby, is still standing at 4068 Honeycutt Street. Mr. Garino may have decided to move after prohibition officers raided the house and found two 10-gallon stills in operation and 18 gallons of ‘white mule’ hidden in a cave under the house; he died in 1937 after eating poisonous mushrooms he had gathered from Balboa Park. In 1921 one of the few other homes that had been built in Venice Park to that time was purchased by John L. Davis, Sr., father of the founder of the San Diego Army and Navy Academy, and moved to a site at the corner of Garnet Avenue and Lamont Street on the academy campus where he lived while serving as the academy’s business manager. By 1930 the San Diego city directory still showed only nine residences on the streets within Venice Park.

The 1930s began as a period of minimal growth in San Diego, and Venice Park. Like the rest of the nation it suffered the economic effects of the Great Depression and like other parts of Pacific Beach it was severely impacted by the provisions of the Mattoon Act, which allowed development projects like the Mission Bay causeway to be paid for with escalating property tax assessments in districts that would benefit from them, like Venice Park. The economic situation improved in the mid-1930s as the depression eased and the county stepped in to take over payment of the Mattoon causeway construction bonds and restore property tax assessments to pre-Mattoon levels. Also in the mid-1930s, the Consolidated Aircraft Company, later known as Convair, moved to San Diego and began employing tens of thousands of aircraft workers in its factories near the San Diego airport, only a few miles from Venice Park over the new causeway.

In 1941 the federal government expropriated much of Pacific Beach northeast of Venice Park and built the Bayview Terrace temporary housing project to accommodate the influx of aircraft workers (this property has never been returned to private ownership and is now the Admiral Hartman Community for military families). Private developers also began building in underdeveloped parts of Pacific Beach, including Venice Park, which was soon transformed by the resulting housing boom. The 1940 city directory had listed only 12 addresses, but nearly 50 were listed in 1950 and by 1960 there were over 125 addresses on Lamont, Honeycutt and Morrell streets and Crown Point Drive in Venice Park. When Lena Kendall died in 1968 her showplace home was demolished and replaced with rows of five-story apartment buildings. These and other multi-story apartments, particularly along Crown Point Drive, doubled the number of residences in Venice Park again by 1980. For the creators of what they called the choicest of suburban beach subdivisions, this would be something to crow about.