The Mexican Pueblo of San Diego covered the territory between National City and Del Mar west of the line of Interstate 805 (the land east of 805 had belonged to Mission San Diego). When San Diego became an American city in 1846 it assumed ownership of these pueblo lands and they were surveyed and platted into pueblo lots, typically a half-mile square and 160 acres. Some of these pueblo lots were sold to individuals; in 1867 Alonzo Horton famously bought six pueblo lots on which he established Horton’s Addition, now the heart of downtown San Diego. The city also offered pueblo lands as inducements to companies that proposed to end San Diego’s isolation by building railroads to the east. These lands were intended not only for the actual rights-of-way and for stations and shops, but also as subsidies to be used by the railroad companies as they saw fit.

The offer of thousands of acres of pueblo lands to the San Diego and Gila Southern Pacific and Atlantic in 1854 and the Texas and Pacific in 1873 did not result in any actual rail-building. In 1880 the city tried again, offering the land it was able to recover from the Texas and Pacific to the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad. Among the pueblo lots offered as subsidies were several in the area that would become Pacific Beach, including Pueblo Lot 1791, a half-mile square centered around today’s Gresham and Chalcedony Streets, and Pueblo Lot 1795, centered around Jewell Street and Grand Avenue. A subsidiary of the Santa Fe, the California Southern Railroad, did actually initiate construction of a railway which eventually connected to the Santa Fe and the east. When this railway met its initial construction milestones, in 1882, the property, including Pueblo Lots 1791 and 1795, was deeded to its real estate subsidiary, the San Diego Land and Town Company.

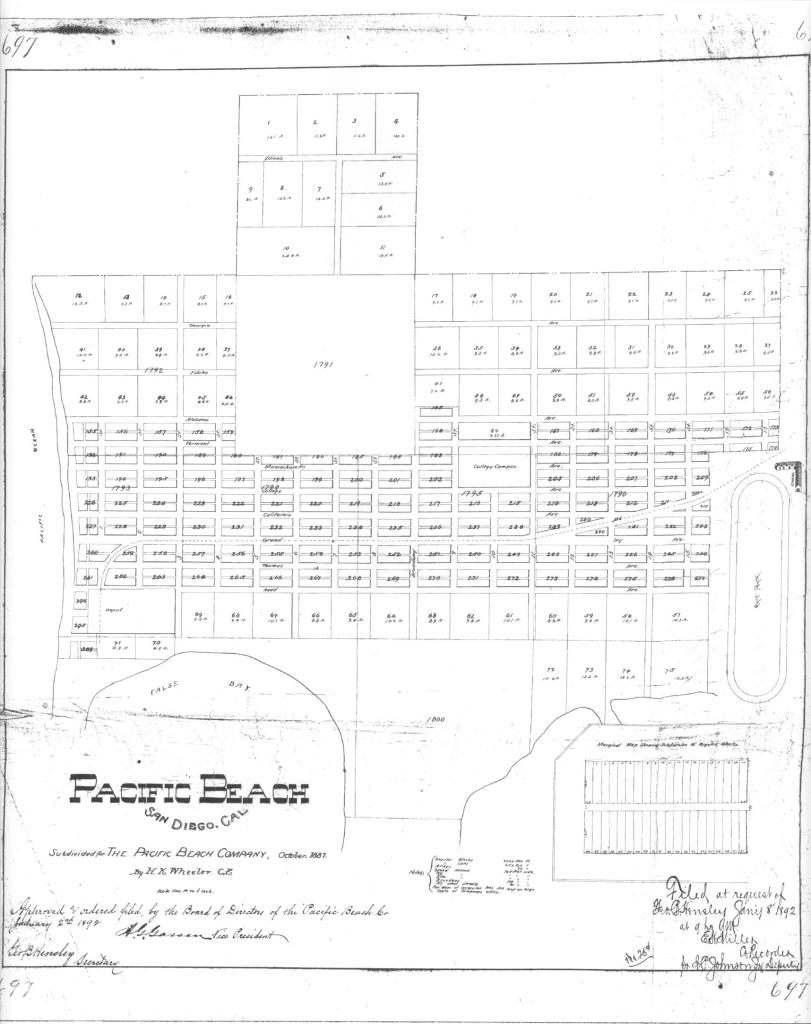

When the Pacific Beach Company was formed in 1887 it acquired Pueblo Lot 1795 from the Land and Town Company and the area within its boundaries became the central portion of the new Pacific Beach subdivision, including most of the College Campus (now Pacific Plaza). However, the Pacific Beach Company did not acquire the adjoining Pueblo Lot 1791, and it was left conspicuously blank in the first recorded subdivision map, Map 697, in 1892.

In 1893 the Pacific Beach Company did buy most of the eastern half of the pueblo lot and it was incorporated into the Pacific Beach subdivision in Map 791, recorded in 1894.

The remaining portion of Pueblo Lot 1791, the west half and the north three-quarters of the north half of the north-east quarter (i.e., the west half and the north 3/16 of the east half), or about 95 of the original 160 acres, was acquired by Abel H. Frost in 1896 for $3500.

Frost arrived in San Diego in 1896 from Michigan, where he had been in the lumber business. In San Diego he joined forces with a niece and nephew and incorporated the A. H. Frost Company to manage his growing real estate empire. Frost also became a director and eventually president of the Folsom Bros. Co., which owned most of the property in Pacific Beach at the time, and when the Folsom brothers retired in 1910 he renamed it the San Diego Beach Company. While his San Diego Beach Company actively developed and promoted its properties in Pacific Beach, his A. H. Frost Company did nothing to promote the Frost tract in Pueblo Lot 1791, and it remained undeveloped for over 25 years (although about two acres at the eastern edge, that portion east of a northerly projection of Ingraham Street, was split off and included with other Frost property in the Congress Heights Addition, between Ingraham, Loring, Kendall and Beryl Streets, in 1914).

In 1923 the A. H. Frost Company sold the property in Pueblo Lot 1791 to the Southern Trust and Commerce Bank, and the portion south of Diamond Street was included in a new Congress Heights No. 2 subdivision. In 1925, the Southern Trust and Commerce Bank transferred both the original Congress Heights and Congress Heights No. 2 subdivisions (minus the few lots already sold) and the remaining undeveloped portion of the Frost tract north of Diamond to the Union Trust Company. This undeveloped portion, from Everts to Gresham between Diamond to Beryl Streets and from Everts to a northerly projection of Ingraham Street between Beryl and Loring, was subdivided in 1926 as North Shore Highlands. Actually, the boundary of Pueblo Lot 1791 lies about 75 feet west of Everts Street, so the row of lots along the west side of Everts is also within the North Shore Highlands subdivision. East of Foothill Boulevard, the western portion of Monmouth Drive and the area south of the Loring Street hill are also included in the subdivision.

When the first unit of North Shore Highlands went on sale in December 1926, the announcement in the San Diego Union highlighted the fact that A. H. Frost had held the property intact for 25 years, ‘refusing to have it spoiled by marketing it at the wrong time or cut up’, and as a result it was a ‘choice, highly improved property in the heart of fast-growing San Diego Beach, without a clutter of old homes on it’. The ‘beautiful sea-view district’ had an ‘inimitable panoramic view’, illustrated by a panoramic photo showing Pacific Beach, Crown Point and Mission Bay, apparently from the top of Loring Street hill (despite the fact that only a few lots were located in the foothills and most were on the coastal plain with little if any view). An ad offered this ‘choicest, most scenic residential property’ for only $940 to $1250, but warned that these present low opening prices would soon be a thing of the past.

The announcement of the opening sale also described a $200,000 improvement program to begin at once, consisting of paved streets, sidewalks and curbs, gas, water, electricity, sewers, ornamental lights and other features. Within a few months the Common Council of the city of San Diego passed a resolution of intention to grade and pave the streets with a Portland cement concrete pavement, and to construct cement sidewalks, curbs, culverts and sewer mains, cast iron water mains and an ornamental lighting system. The lighting system was to consist of reinforced concrete lighting posts, globes, refractors, lamps, and pot heads, along with cables and other appurtenances. The improvements were to be paid for by serial bonds, to be repaid at 7 percent interest by charges upon an improvement district which included all the property lying within North Shore Highlands.

By mid-1927 the promised improvements were well under way, according to George M. Hawley in the Evening Tribune. The Hawley organization had taken an exclusive contract for the promotion and sale of the North Shore Highlands tract and their July 23 ad in the Tribune followed a familiar script when they invited the public to a good luncheon and concert at their big tent at Diamond and Fanuel Streets, but also added a contemporary flourish; free airplane trips over the north shore district in a Ryan monoplane, ‘same type as carried Lindbergh over the Atlantic’ (Charles Lindbergh’s famous solo flight from New York to Paris in the ‘Spirit of St. Louis’, a San Diego-built Ryan monoplane, had occurred two months earlier, in May 1927).

The promoters of North Shore Highlands had envisioned a ‘new high-class residential subdivision’ with large lots and ‘race and building restrictions that would make it highly desirable’. The lots were large; the standard lot was 50 feet wide rather than the 25-foot width of most lots in Pacific Beach, and lots in the foothills area and on the strip along the west side of Everts Street were even larger. Race restrictions meant that the lot could never become the property of, or even be occupied by, ‘any person other than of the Caucasian race’ (unless they were a servant or employee of a Caucasian occupant). Among the building restrictions were requirements that the property could only be used for a single, private, residential purpose, the residence erected on the premises would be limited to one story and could not cost less than $4000, no common shingled roofs would be permitted, and no pepper, eucalyptus or cypress trees could ever be planted (black acacia could be planted, but only between the cement walk and the curb).

While the promoters proclaimed that these restrictions made North Shore Highlands highly desirable, and the introduction of the San Diego Electric Railway line to La Jolla via Mission Beach and Pacific Beach in 1924 had improved access to San Diego, potential purchasers were apparently not impressed; of the more than 300 lots in the subdivision only six had been purchased, and only three residences built, by 1930 (and the owner of one of these lots and residences was one of the promoters).

In addition to high purchase prices and the added costs of the building restrictions, purchasers of property in an improvement district like North Shore Highlands were required to pay an annual assessment to service the improvement bonds, and under the Mattoon Act of 1925 would also be responsible for a share of the assessments of any residents of the district who defaulted (two lots in North Shore Highlands were foreclosed and offered for sale by the city for non-payment of the improvement bond). The negative effect that the great depression of the 1930s had on the real estate market must have also impacted sales. Only ten residences could be counted in an aerial photo from 1935, after the tract had been on sale for more than eight years, and the 1937 San Diego city directory listed only ten addresses on its streets.

The completion of the causeway across Mission Bay to Crown Point in 1931 further reduced travel time to San Diego, the Mattoon Act was repealed in 1933 and the economy began recovering from the great depression in the mid-1930s. In 1937 a new promotional campaign by E. G. Anderson Co., developers of Crown Point, announced the ‘opening’ of North Shore Highlands, ‘prices from $500 . . . all improvements in and paid for . . . no bonds, no assessments’. The E. G. Anderson company also offered to build a ‘distinctive dwelling’ on a purchaser’s lot. Lot sales in North Shore Highlands began to respond; in the 1200 and 1300 blocks of Missouri Street the number of homes listed in the San Diego city directory increased from 1 in 1937 to 3 in 1938, 6 in 1939 and 8 in 1940.

The Consolidated Aircraft Corporation had relocated to San Diego in 1935 and in 1940, in anticipation of World War II, greatly expanded its San Diego manufacturing facilities to produce thousands of B-24 Liberator bombers. Tens of thousands of new workers migrated to San Diego to staff the factories, and all these new aircraft workers needed a place to live. The federal government responded to the acute housing shortage by building entire communities of temporary housing, including the Los Altos Terrace housing project just across Loring Street from North Shore Highlands. Commercial real estate developers followed suit by building inexpensive ‘standard built’ homes in existing housing tracts like North Shore Highlands.

Newspaper ads in 1941 invited the public to inspect standard built homes by Convers and Donahoe in the 1300 blocks of Missouri, Chalcedony and Law streets; ‘we have not tried to create something new but have incorporated in the floor plan the last word in conservative living. Ten homes completed or under construction’. The ad for Little Castles, Inc., reported continuous and increasing demand for well built homes in the Highlands of beautiful Pacific Beach; ‘Two-bedroom homes ranging from $3295 to $3895, turn-key job – no extras. A minimum down payment, balance like rent. Offices at 1311 Chalcedony St’.

Sales of standard built homes within North Shore Highlands exploded; the San Diego city directory showed that the number of homes in the 1200 and 1300 blocks of Missouri Street increased from 8 in 1940 to 28 in 1942. The comparable blocks on Chalcedony and Law streets each had one home in 1940 but there were 21 homes on Chalcedony and 16 on Law in 1942 (7 of these 65 homes were listed as vacant in 1942, presumably completed but not yet sold). By 1945 the number of homes on these streets had grown to 30, 24 and 22, well over half of the 40 lots on each street, and none were vacant. Similar growth occurred throughout the subdivision, at least outside of the foothills area where the steep terrain made construction of inexpensive homes impractical, and by 1950 these areas had been built out. And with zoning regulations still favoring single-family residences many of these standard built homes from the 1940s are still standing.

North Shore Highlands has a unique history and followed a separate development path from the rest of Pacific Beach, but what really sets it apart from the surrounding neighborhoods today are the ornamental street lights which still line the streets and even extend along Fanuel Street to Garnet Avenue and along Loring Street to Cass Street (at the time the lights were installed the highway between San Diego and Los Angeles ran through Pacific Beach along Garnet and Cass; Fanuel and Loring would have been the main access routes to this highway). Although the lights have been removed from Foothill Boulevard they can still be seen all the way up Loring Street hill and on Monmouth Drive. Ironically, while the ornamental street lights were installed in the 1920s to mark North Shore Highlands as a high-class residential community, they were not actually turned on until 1944, when the community had been largely settled by ordinary people in ‘standard built’ homes.