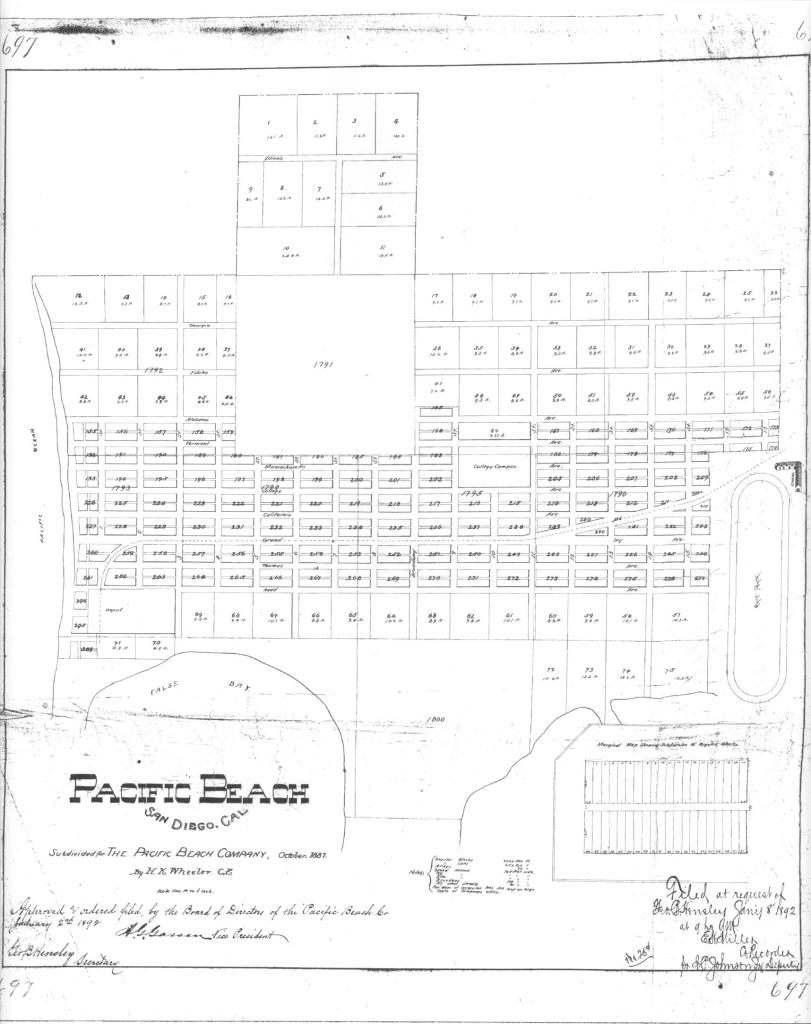

Pacific Pines is a subdivision in Pacific Beach surrounded by Reed Avenue, Pacific Beach Drive, and Jewell and Lamont streets. The four blocks that became Pacific Pines in 1926 had originally been included in the Pacific Beach Company’s 1887 subdivision map as residential blocks 283, 284, 305 and 306, surrounded by Reed and Hubbell avenues and Ninth and Eleventh streets and separated by Gassen Avenue and Tenth Street. However, few lots were sold south of Reed Avenue (or north of Alabama Avenue, now Diamond Street) and in 1892 an amended map of the Pacific Beach subdivision, Map 697, re-subdivided the area south of Reed by eliminating the east-west avenues (including Gassen and Hubbell) and most of the streets (including Ninth and Tenth). The former residential blocks (and the former avenues and streets) were consolidated into ‘acre lots’ of around 10 acres each, intended for agricultural purposes. Between Reed and what had been Hubbell avenues, the area between Ninth and Tenth streets (including what had been Ninth and Gassen Avenue) became Acre Lot 62; the area between Tenth and Eleventh (including Tenth and Gassen) became Acre Lot 61. Reed Avenue and Eleventh (now Lamont) Street continued to exist on map 697, which also transformed much of the area north of Alabama Avenue into acre lots.

Although property in these areas hadn’t sold well as residential lots, the acre lots proved to be extremely popular and thirteen were sold within the first few months after map 697 was recorded in January 1892. One of these was Acre Lot 61, sold to C. H. Raiter, a director of the First National Bank of Alexandria, Minnesota, who had spent the past winter in the vicinity. Mr. Raiter paid $1010, $100 an acre for the 10.1-acre parcel, in April 1892. When he left for home a few weeks later, the San Diego Union reported that he intended making this his home, in the winters at least, and had sent instruction to have the ten-acre tract put equally into oranges and lemons and to reserve a good building site. The property was to be piped, fenced and broken and planted as soon as possible, and Mr. Raiter intended coming back in the fall to superintend the construction of a residence.

The Raiters did return, in the winter at least, and in February 1894 Mrs. Anna Raiter recorded the deed for the adjoining Acre Lot 62, paying $940 for the 9.4 acre plot. However, Mr. Raiter never did superintend the construction of a residence; no improvements were ever assessed for acre lots 61 and 62 although the property was apparently planted to orange and lemon trees and ‘had 1000 little cypress plants put around it’. In 1895 the Union reported that Mr. Raiter was piping his entire tract and when the Raiters arrived for another winter visit in February 1897 and the Santa Fe train rolled him in sight of the beach, his orange and lemon grove with its surrounding hedge surpassed his most sanguine expectations and he (again) decided to make San Diego the home of his retirement.

Although the Raiters never built a retirement home they did continue to visit the San Diego area in the winter months. In February 1899 they were on the Union’s list of hotel arrivals at the Horton House downtown, and were said to be visiting with Sterling Honeycutt, then a leading lemon rancher and landowner in Pacific Beach. In April 1902 the Raiters were listed as arrivals at the Lakeside Hotel. It was during that trip to the San Diego area that they sold their Pacific Beach property to D. C. Campbell, who then sold it to Alexander and Mary McGillivray, wealthy absentee owners from Dickinson, North Dakota.

The amended Pacific Beach subdivision map of 1892, Map 697, had ended at the southern boundary of acre lots 61 and 62 but in 1898 the trustees of the Pacific Beach Company purchased the northern 61 feet of Pueblo Lot 1800, immediately south of and adjacent to these acre lots. Another five-acre parcel at the eastern edge of Pueblo Lot 1800, immediately south of this 61-foot strip and opposite Acre Lot 61, was purchased by Eliza Turner. In the remainder of Pueblo Lot 1800, the eastern half was subdivided as the Fortuna Park Addition in 1902 and the western half (except for a six-acre parcel in the southwestern corner) as Second Fortuna Park in 1903. The five-acre parcel opposite Acre Lot 61 was subdivided by Sterling Honeycutt in 1909 as Sterling Park.

Many acre lots had been developed as lemon ranches and lemon cultivation dominated the economy of Pacific Beach for the decade after 1892, but by the first years of the twentieth century the agricultural economy had begun to fade and real estate operators led by Folsom Bros. Co. were converting lemon groves into residential blocks by grading streets and building concrete curbs and sidewalks. One of the first areas to be developed was Sterling Honeycutt’s former lemon ranch between Garnet and Grand avenues and Jewell and Lamont streets, and one of the first streets to be graded, ‘curbed’ and ‘sidewalked’ was Kendall, the former Tenth Street (San Diego had decided in 1900 to require all street names to be unique and there were already ‘numbered’ streets downtown).

Grading of Kendall Street between Garnet and Grand was done in April 1907 and there were plans to grade it all the way to the bay to make a ‘splendid entrance’ to Fortuna Park, south of acre lots 61 and 62 and then controlled by Folsom Bros. Cement sidewalks were also planned for Kendall between Garnet and Grand, to be extended south to Reed Avenue and later all the way to Mission Bay. Since the 1892 subdivision map had eliminated Tenth Street south of Reed Avenue this route to Fortuna Park and Mission Bay was then private property, but in April 1907 the McGillivrays reconveyed the westerly 80 feet of Acre Lot 61 to the city for use as a street and public highway. In June 1907 the city ‘confirmed and accepted’ the conveyance and the property was ‘set apart as a part of Kendall Street’. This part of Kendall Street was graded shortly afterward, completing what the Union called a ‘main thoroughfare from hotel to bay’ (the Hotel Balboa, the former San Diego College of Letters building, was at the other end of Kendall, across from its intersection with Garnet Avenue).

However, the opening of a main thoroughfare through acre lots 61 and 62 did not lead to their development into residential blocks, at least not right away. Mr. McGillivray died in 1907 and although Mrs. McGillivray acquired additional property in Pacific Beach and Fortuna Park, she continued to live in North Dakota until her death in 1924 (the McGillivray House in Dickinson has since become famous as a ‘haunted house’). In 1925, acre lots 61 and 62 were acquired by Exchange Securities Corp, headed by J. H. Shreve, and then passed to Roy Snavely and Charles Brown, former realtors from Pasadena. Snavely and Brown also acquired the 61-foot strip south of acre lots 61 and 62. In May 1926 they announced that the 20-acre tract would be subdivided and would be known as Pacific Pines, since it was surrounded by a row of beautiful pine trees (presumably the ‘1000 little cypress plants’ put around the property in the 1890s). The Union reported that it was the aim of the owners to preserve every tree on the tract, and all streets would be improved with concrete paving, curbs and sidewalks. Spanish style construction would be suggested to everyone building a residence.

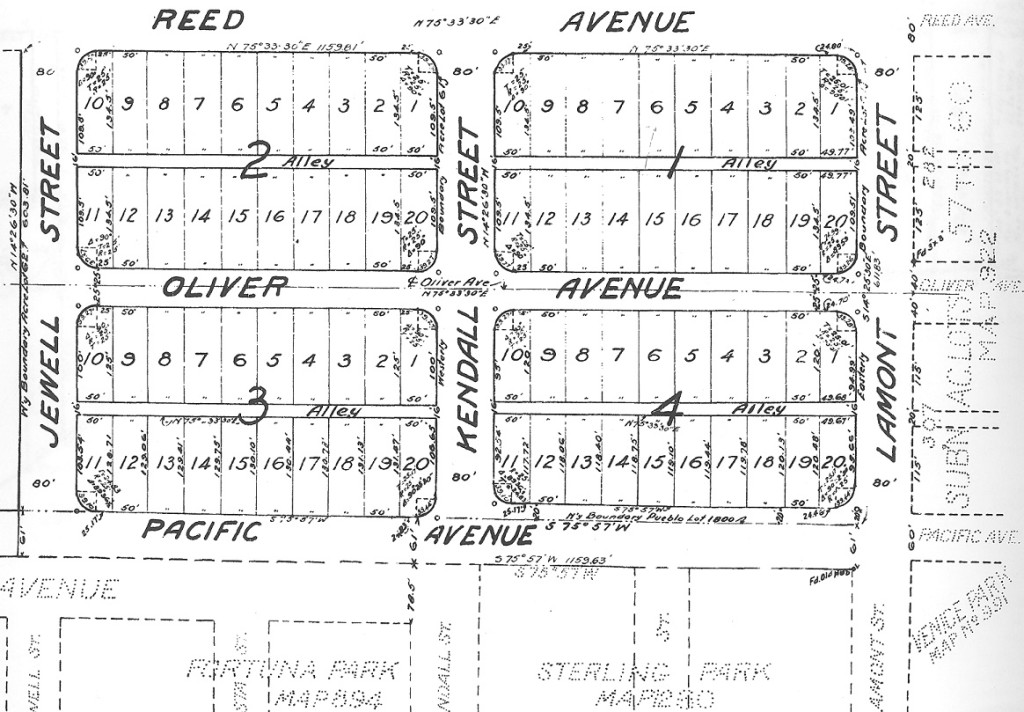

The subdivision map of Pacific Pines, Map 1917, was recorded in June 1926. Other former acre lots in Pacific Beach had already been returned to residential blocks, including the 1904 Subdivision of Acre Lots 57, 58, 59 and 60, Map 922, just to the east across Lamont Street. These earlier re-subdivisions generally recreated the blocks of the original 1887 map by replacing the streets eliminated in the 1892 revision, usually with the original pattern of 40 25- by 125-foot lots and a 20-foot alley, and with the original block numbers. At Pacific Pines, Kendall Street had already been replaced and Map 1917 also set aside the westerly 80 feet of Acre Lot 62 as Jewell Street. An extension of Oliver Avenue from Map 922 replaced the original Gassen Avenue and recreated the four blocks which had existed here before the acre lots. However, these blocks looked somewhat different than most others in Pacific Beach; 20 50-foot lots with depths that depended on the block. In blocks 1 and 2, between Reed and Oliver, the lots were all 134.5 feet deep. In block 3, south of Oliver and west of Kendall, lots 1-10 were 125 feet deep and lots 11-20 were about 130 feet deep. In block 4, east of Kendall, the lots were all about 120 feet deep. The alleys were 16 feet wide and Oliver Avenue was 50 feet wide, narrower than the standard 80-foot streets in Pacific Beach (including Reed Avenue and Kendall, Jewell and Lamont streets) and the 75-foot streets in Fortuna Park to the south. Another unusual feature of the Pacific Pines subdivision map was the wide curvature of the street corners that cut off a portion of corner lots.

The Pacific Pines subdivision map also included another street, Pacific Avenue, along its southern boundary. East of Kendall, opposite the Sterling Park subdivision, the Pacific Pines map set aside 81 feet for Pacific Avenue. West of Kendall, Pacific Pines adjoined Fortuna Park, which already had a street named Pacific Avenue, 78.5 feet wide, along its northern boundary. In this area the Pacific Pines map placed Pacific Avenue in the 61-foot strip, which, combined with the existing 78.5-foot avenue in Fortuna Park, would have created a street 139.5 feet wide. The developers announced that Pacific Avenue in this area would be divided into two roadways with a park in the center, a solution that can still be seen today. Pacific Avenue was renamed Pacific Beach Drive in 1935 to avoid any confusion with Pacific Highway, the new route from downtown to Del Mar through Rose Canyon (although the old name still appears on curbstones).

Brown and Snavely opened their new subdivision for public inspection and sale in June 1926. The Union announced that the Pacific Pines company had adopted ‘the subdivision of distinction’ as its slogan and that it would provide home sites where formality was not demanded but where restrictions had been provided. It was near the ocean and bay, bordered by rows of stately pine trees. In September the city council passed a resolution of intention that all streets in Pacific Pines were to be graded and paved with five inch Portland cement pavement, concrete curbs, sidewalks, cast iron water mains, fire hydrants, etc. The contract was awarded to Harris & Wearn in December 1926, and paving was completed in 1927, giving Pacific Pines some of the first paved residential streets in Pacific Beach. The curved curbs and sidewalks around the wide street corners, particularly the intersection of Oliver and Kendall at the center of the tract, became a signature feature of Pacific Pines.

The opening of Pacific Pines for inspection and sale coincided with the opening of several other subdivisions in Pacific Beach, including North Shore Highlands, Crown Point, Braemar and the Palisades, and all of these tracts initially experienced disappointing sales. In Pacific Pines only five lots were sold in 1927, and only one residence built, a stucco cottage valued at $9000 for J. P. Harris (of Harris & Wearn, the paving contractor). Mr. Harris’ home faced the ‘park’ laid out by his company in the wide expanse of Pacific Avenue. The number of addresses on the streets of Pacific Pines grew to 5 in 1929 and 7 by 1930, but growth stalled in the 1930s and only one additional address had been added by 1940 (6 of these early homes remain, recognizable by the Spanish style construction suggested to everyone building a residence in Pacific Pines).

Consolidated Aircraft moved to San Diego in 1935 and built a manufacturing complex next to the airport downtown. In 1940 Consolidated began production of the B-24 Liberator bomber, hiring tens of thousands of aircraft workers who mostly arrived from out of town. Thousands of military personnel were also stationed in San Diego and many more began arriving after war was declared in December 1941. Even before the government stepped in to develop temporary housing projects for defense workers, including several in Pacific Beach, commercial developers began meeting the demand for affordable housing in existing residential neighborhoods like Pacific Pines.

In July 1941 the Original Dennstedt Company advertised that 19 Title VI homes were under construction at Pacific Pines, a tree-shaded, home-like atmosphere in a marine location 7 minutes from San Diego, and more than thirty were planned. $250 down and no ‘extras’ was all you would need to move into a Dennstedt luxury home. Dennstedt ads emphasized that each home was different – original and individual; a buyer could choose from Norman, Colonial, Cape Cod, English, and others. The $250 down payment applied to 2-bedroom homes; 3-bedrooms required $350 down. Dennstedt was joined by other developers and affordable 2-and 3-bedroom homes in Pacific Pines were sold nearly as fast as they could be built. The 1941 San Diego city directory had listed 8 addresses in Pacific Pines but by 1942 the list had grown to 67 addresses and in 1943 77 addresses were listed on these four blocks of 20 lots each. The city directories also showed that most of these residents were aircraft workers or military personnel.

Seventy-five years have passed since that Pacific Pines building boom and some of those homes have since been replaced by apartment buildings or town homes, but many remain, still recognizable as Cape Cod, English or the even earlier Spanish style. Some of the trees growing in Pacific Pines may also be the original pine (or cypress) trees that the developers had aimed to preserve.