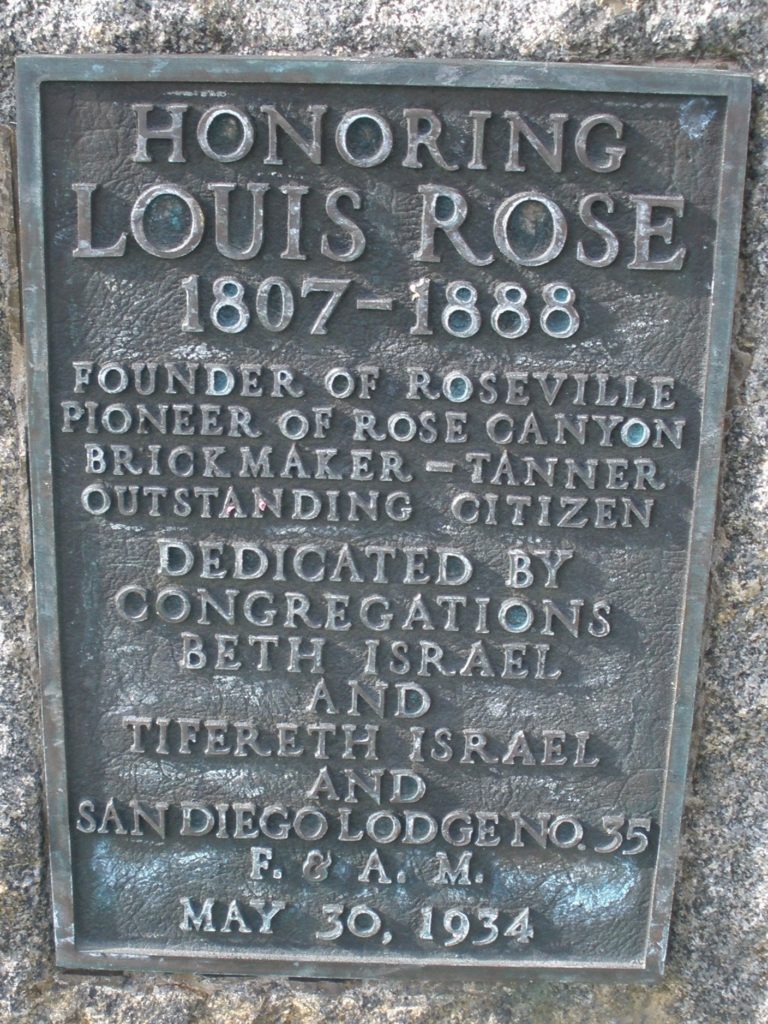

San Diego’s Rose Canyon is endowed with what has been described as an inexhaustible supply of clay, ideal for making bricks, and millions of bricks were produced there until the last brickyard closed in the mid-1960s. The canyon was named for Louis Rose, who had come to San Diego in 1850 and beginning in 1853 had acquired most of what was then called La Cañada de las Lleguas. A monument to Rose near the northern entrance to Rose Canyon, on what was once the median of the Pacific Highway and is now a lawn on the University of California campus, credits him with being a brickmaker as well as a tanner, outstanding citizen and pioneer of Rose Canyon. In fact, while Rose was a prominent citizen of early San Diego and his tannery made him a Rose Canyon pioneer, there is no evidence that he was actually involved in brickmaking.

In 1861 Rose was forced to sell his holdings in the canyon to a creditor, Lorenzo Sota, and in 1875 Sota’s daughter and heir Rosa sold the canyon to Adolf G. Gassen. By the late 1880s San Diego had developed to the point where substantial multi-story buildings were being built downtown and in October 1888 the San Diego Union reported that bricks were being ‘burned’ in the Rose Cañon kiln for the Pauly & Gassen building. By November 1888 the news was that work on the Pauly-Gassen block, Fourth and E streets, would be rushed as soon as the material could be hauled to the ground. The first load of brick had been brought in the day before from the yard of Quereau & Bowman in Rose’s Canyon and no building in the city would have a better article for foundation or walls (the brick Pauly-Gassen Building is still standing on the northeast corner of Fourth and E).

In April 1890 the Union reported that Charles H. Hill had secured a ten-year lease of eighty acres of land in Rose Canyon that was said to be well supplied with good clay for brick. He also began work on a ‘continuous brick kiln’ capable of firing 9 million bricks a year. According to the Union the kiln was the invention of Max Boehncke and was a large circular or elliptical structure divided into sixteen compartments, each large enough to hold a day’s work of the brickyard. In a continuous kiln of this type newly molded clay bricks would be loaded into one of the compartments and remain there while the compartment was advanced through the different phases of brickmaking each day by moving the fire to a new compartment and altering the flow of air between compartments. Outside air would be drawn first through cooling compartments, cooling fired bricks and warming the air before it entered the firing compartments, where it combined with fuel in combustion that raised temperatures to over 2000° F, vitrifying or ‘burning’ the bricks. The exhaust from the firing compartments would then be fed through ‘water smoking’ compartments, warming and drying the unfired bricks and preparing them for firing, before escaping through a chimney in the center of the structure which produced the draft for the entire process. At any given time five or six of the compartments would be for water smoking, three compartments would be used for firing the dried bricks and four for cooling the bricks after firing. Each day a compartment of cooled bricks would be emptied and made available for another load of newly molded bricks, perpetuating the continuous process. The kiln would be 100 feet long and 60 feet wide and was expected to be completed by the middle of the summer.

By the middle of summer, in July 1890, the Union reported that the continuous brick kiln recently built by C. H. Hill in Rose Canyon was in operation, turning out 25,000 bricks per day. The company had the contract for furnishing the brick for the new opera house and was already delivering the material. The brick delivered so far were of particularly fine quality, being evenly burned and of uniform hardness. Mr. Hill also expected to find a market shipping brick by sea; vessels leaving San Diego often took on rock or sand ballast, which they had to pay for, so if a load of bricks were taken on instead of ballast a ship might save money even without charging freight.

The Union also reported that Charley Hill’s continuous brick kiln in Rose Canyon had become a ‘curiosity’ and was visited by a large number daily. The curiosity might have been due to the kiln’s peculiar 114-foot high chimney. During construction it was found to be out of plumb; some said the mason had made a mistake and others claimed that it had settled unevenly as it rose and gained weight. The builders attempted to straighten the unfinished portion of the chimney with the result that it not only ‘leaned’ but was ‘bent’ at the top. There are reports that its lean was further increased by flooding of Rose Creek in 1916, when water stood six feet deep around the chimney, and possibly even by earthquakes on the Rose Canyon fault. In the 1930s measurements of the chimney showed that it leaned 3° 26” from vertical and the center of the top was 6.3 feet from the center of the bottom.

A Union article in December 1890 stated that the seven ‘pressed brick machines’ at Rose Canyon brickyard had been started up for the first time and Charles Hill said that they would turn out from 20,000 to 25,000 bricks a day to begin with, but when running at full capacity 100,000 could be made. An order for 75,000 bricks for the three additional stories of the George J. Keating building would be filled first (the Keating building, its upper three stories made of red brick, is still standing at Fifth Avenue and F Street downtown). In January 1891 Hill said that 100,000 bricks would be ready to leave the kiln, and that some would go north to fill orders (the California Southern Railroad built a siding at the brickyard and named it Ladrillo, Spanish for brick). As expected, some bricks were also shipped by sea; in February 1891 the Union reported that the schooner David Park was taking on 82,000 bricks from the Rose Canyon yards for Eureka. In March the schooners Bertha Dolbeer and Lottie Carson sailed for Eureka with 26,000 and 86,000 bricks, respectively, from Rose Canyon. In May it was the schooner Ruby A. Cousins taking 60,000 bricks from the Rose Canyon brickyard to Eureka. Other local projects also required bricks; in 1891 E. W. Scripps, the newspaper tycoon, contracted with Charles Hill to furnish 40,000 bricks to begin work on his planned family residence at Miramar that became the Scripps Ranch.

Like other land that the American city of San Diego had taken over from the former Mexican pueblo, Rose Canyon was divided into pueblo lots, generally a half mile square and 160 acres. A. G. Gassen’s purchase from Rosa Sota had included four pueblo lots in the lower part of Rose Canyon, lots 1788, 1787, 1778 and 1777. In August 1891 G. A. Garrettson and Jacob Gruendike incorporated the Rose Canyon Brick Company and bought Pueblo Lot 1778 from Gassen, apparently giving them control of Hill’s continuous kiln. According to the San Diego Union the Rose Canyon company seemed to be doing a big business and employed a large number of men. Two million of their bricks were used in the upper three floors of the Fisher Opera House which once stood on Fourth Street between B and C streets downtown, previously said to be Hill’s customer.

However, the brickmaking operations that the Rose Canyon Brick Company had taken over from Hill apparently extended into the adjoining Pueblo Lot 1787, which Gassen still owned, and in May 1893 Gassen sued the Rose Canyon company to recover possession of lot 1787, which his lawsuit claimed the defendants had ousted him from in August 1891. The lawsuit was decided in Gassen’s favor; he was awarded Pueblo Lot 1787 and $100 damages and the Rose Canyon company was ordered to refrain from digging up or removing clay from the premises or removing any machinery. A descendant of D. F. Garrettson noted later that when the property was surveyed the boundary went right through the brick kiln. Although the Rose Canyon Brick Company continued to exist and owned the Rose Canyon property until it was sold in 1938 for nonpayment of state and county taxes, Gassen’s lawsuit put an end to its brickmaking operations.

Brickmaking in Rose Canyon resumed in 1901 when Gassen sold 7 acres in the northwest quarter of Pueblo Lot 1787 to James R. Wade, a masonry contractor. In April 1904 Wade, his brother William and Homer G. Taber founded Union Brick Company. In August of that year Taber announced that new machinery would be installed at the company’s Rose Canyon plant giving it a capacity of 35,000 bricks per day. Two years later, in 1906, the Union reported that arrangements had been completed for the removal of the Union Brick plant from its Rose Canyon location to near the foot of 22nd Street, although Rose Canyon remained the source of the company’s clay. The owners would build a boarding house for employees who wanted to live near the new brickyard, as the company preferred they should.

In 1908 the Union Brick Company’s stock and plant was acquired by J. T. Maechtlen, J. W. Rice and General E. C. Humphrey. The Union reported that they expected to have the plant in operation shortly, employing about 25 men and turning out between 25,000 and 30,000 bricks a day. This plant was still downtown; in an ad for Union Brick Company, ‘manufacturing first class building bricks’, on New Year’s day 1909 J. J. Maechtlen was listed as president, J. W. Rice as vice president and E. C. Humphrey as secretary, office 510 Granger Block, yard foot 23rd St. The 1911 city directory indicated that the office and yards were at the foot of 23rd St. and that clay pits were located in Rose Canyon. Presumably the four brickyard laborers who were counted in Rose Canyon in the 1910 federal census, all Spanish-speaking and born in Mexico, worked in the clay pits. John W. Rice became president of Union Brick Co. in 1910 and in 1916, when contributions were being solicited for Mercy Hospital campaign fund, as ‘San Diego’s sole manufacturer of bricks’ he forwarded a note to campaign headquarters to the effect that he would make his contribution in the form of bricks to be used in construction of the hospital buildings.

By 1917 the company had moved its yard from the foot of 23rd Street back to Rose Canyon. Other construction projects in San Diego created an additional demand for bricks and the ‘sole manufacturer’ stepped up production. A story in the Evening Tribune in 1921 described how a Fordson tractor at the Union Brick Company in Rose Canyon was ‘moving a mountain at the rate of 25,000 bricks a day’; turning a mountain of clay into buildings for the naval training station, marine base and naval hospital that were then being built in San Diego by the federal government. One man on the Fordson was plowing the clay pit with a 14-inch deep tillage bottom and carrying it to a hopper, doing the work that it formerly took four men and eight horses to accomplish. In 1923 the Union Brick Company took out an ad in the San Diego Union to correct some misleading statements made in regard to the brick situation in San Diego. Apparently the Union had stated that 1800 cars of brick were shipped into San Diego the previous year. This was absolutely incorrect, according to the ad; all these bricks had been shipped from Rose Canyon, which is within the city limits. The level of activity in the Rose Canyon brickyard was also reflected in the 1930 census, which showed that a dozen Spanish-speaking Mexican natives were then employed as laborers there and living with their families in the vicinity.

When the Union Brick Company moved its brickyard from 23rd Street back to Rose Canyon, it also closed its office there and moved its business address to 3565 Third Avenue, the residence of president John W. Rice (which of course was made of brick). In 1946 John W. Rice turned the company over to his son, John W. Rice Jr., although he continued to go to work at the brickyard daily for many years. Under the younger Rice the company undertook a number of improvements to boost production to keep pace with San Diego’s growth. One improvement was substitution of the traditional sand-molded process to the more modern wire-cut method. In 1952 the Union Brick Company supplied the bricks for the new Sears, Roebuck building (500,000 bricks) and Telephone Company building (250,000) in Normal Heights. Production tripled to 12 million bricks a year by 1954.

In 1955 the company announced plans for another expansion to initiate production-line techniques and year-round production. Up to that time the company’s production season had been limited to April 1 through September 15, based upon prospects for favorable weather. Untimely rains could ruin quantities of unfired bricks stacked for four to six weeks in the drying yard at the Rose Canyon plant. The new process would include a tunnel for continuous drying under controlled humidity conditions and a new continuous kiln for pre-heating, burning and cooling the brick.

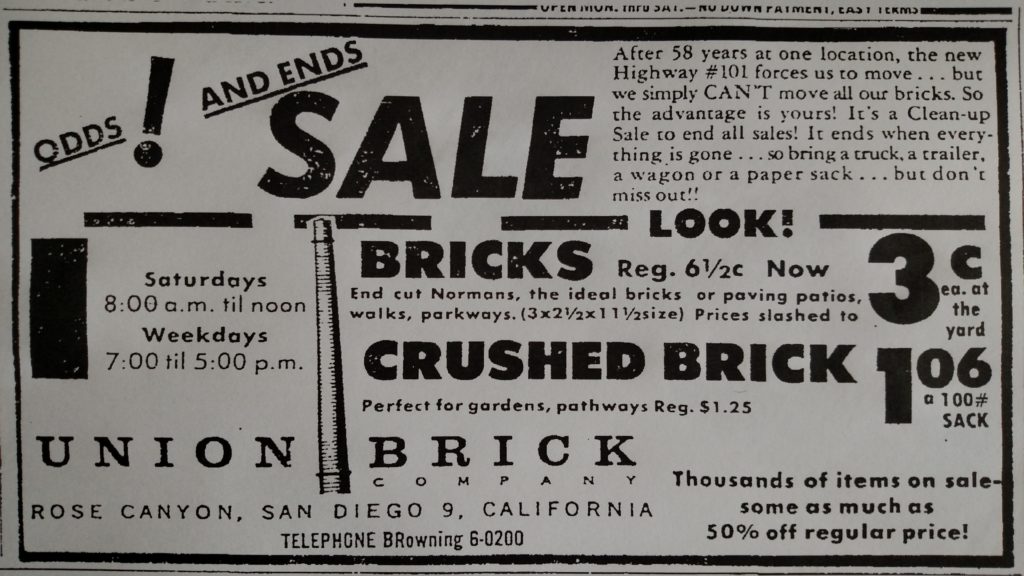

While Rose Canyon had been an ideal location for brick production it was also a natural route of travel to and from San Diego. San Diego’s main rail link to the outside world ran through the canyon and a road first opened in 1894 became the Pacific Highway in the 1930s. With increasing numbers of travelers passing the brickyard along their route, its leaning chimney became one of San Diego’s most prominent landmarks. In December 1958 it was even decorated for Christmas; the Union reported that a helicopter was used to lower a likeness of Santa Claus onto the leaning chimney of the Union Brick Yard in Rose Canyon. However, traffic continued to increase and in 1960 the news was that an additional four lanes of U. S. 101 would force the Union Brick Company to move from Rose Canyon, although in recognition of its landmark status the ‘leaning tower of Rose Canyon’ would be spared.

The chimney’s reprieve turned out to be a short one, however; in January 1962 the ‘leaning smokestack’ toppled over during heavy winds accompanying a rainstorm with only the bottom third still standing. A photo in the Union showed a figure of Santa Claus, which had once stood atop the tower, lying among the ruins. A couple of days after the leaning chimney blew down, Union Brick president John W. Rice Jr. proposed that a replica, tilted at a similar angle, would be built as a monument to the original at the company’s new location in Sorrento Valley. The company’s sales manager added that the area, without the leaning chimney, looked like a ‘woman without her earrings’ and said that construction, using bricks from the original stack, would begin as soon as approval was granted. Approval was not granted and the replica chimney was never built, but Rose Canyon’s brick heritage has been commemorated in other ways. In 1963 the masonry contractor for the new Rancho Bernardo community announced that more than 25,000 bricks had been salvaged from the ‘leaning chimney of Rose Canyon’ and would be used in fireplaces in Rancho Bernardo homes and apartments. And more than 50 years after the chimney fell and the last brick was made in Rose Canyon, when the Karl Strauss brewery and tasting room opened in Rose Canyon in 2013, one of the items on its menu was a cask-conditioned barleywine named Union Brick.