Pacific Beach was first subdivided and lots offered for sale in 1887. The first residents were attracted to what was expected to be a college community surrounding the San Diego College of Letters, located where Pacific Plaza is now. However, the college closed in 1891 and the community was soon transformed into a center of lemon cultivation. Some of the lemon ranchers came from Southern states and brought their entire households, and even their servants, with them.

In 1899 Mrs. Carrie Belser Linck bought a lemon ranch on acre lot 33, at the northwest corner of Lamont and Chalcedony streets. She came from Tennessee along with her mother, three sisters and brother Charles. When Charles Belser arrived in January 1900 to assume management of his sister’s ranch, the San Diego Evening Tribune noted that ‘Mr. Belser of Nashville Tenn. and his colored man servant had arrived’. In June 1900 the San Diego Union reported that in Pacific Beach Belser & Co., lemon packers, were shipping cars east at the rate of two a week, but residents were complaining that they had seen nothing of the ‘census man’ and hoped he would not forget them. The census man did come around on June 22 and enumerated the Linck household, including 18-year old John Miller, servant, for the 1900 United States census. The census form had a column for ‘color or race’ and John Miller was listed as ‘B’, while Mrs. Linck, the Belsers and the other 200+ residents of Pacific Beach at the time were listed as ‘W’. John Miller may well have been the first Black resident in Pacific Beach.

Mrs. Linck sold the ranch in May 1901 and moved to San Francisco with her sisters, the ‘Misses Belser’, but there was no further news of Charles Belser or John Miller. In 1903 the Tribune reported that Mr. and Mrs. Roberts from Arkansas had moved into the upper Baker ranch; ‘They bring with them a carload of household goods, a colored family for servants besides horses and dogs’ (the upper Baker ranch was on acre lot 30, the northwest corner of Chalcedony and Olney streets). Lettie Lee Roberts died in 1905, Preston Roberts moved downtown in 1907, and there was no additional information about the ‘colored family’ who had accompanied them to Pacific Beach and would presumably have been its first Black family.

In 1900 Fred T. Scripps, brother of newspaper tycoon E. W. Scripps, bought several acres of land along the shore of Mission Bay at the southwest corner of Pacific Beach and by 1901 had completed an imposing bayfront home, Braemar Manor. His wife Sarah, better known as Emma, was an avid gardener who developed the elaborate landscaping on the grounds surrounding their home. An estate like this required domestic help, and the 1905 San Diego City Directory listed ‘Corushia’ Tate as domestic and Frank Tate as coachman for F. T. Scripps. In the 1906 directory Frank Tate was a gardener and Crozier Tate a cook living in Pacific Beach, and the 1908 directory listed Frank as cook for F T Scripps and also James Tate as a gardener in Pacific Beach.

The 1910 United States census attempted to account for everyone in a ‘dwelling’ and to list, among other things, their name, relation, age, ‘color or race’, marital status and number of years married, place of birth and occupation. At the Scripps dwelling, in addition to Frederick T., head, and Sarah E., wife, and their two sons and two daughters, the census also listed James, Josephine, Frank and ‘Crosha’ Tate, servants (as well as Frederick Hagan, chauffeur). James, 49, and Josephine, 50, were from Alabama and had been married 35 years. His occupation was gardener and hers was ‘house’, presumably a maid. Frank was 31 and also from Alabama, and Crozier, 26, was from Missouri. They had been married for 7 years. He was a gardener and she was a cook. Although the data on the census form doesn’t connect all the dots, in fact James and Josephine Tate were Frank Tate’s parents and Crozier was his wife. In the ‘color or race’ column, James, Josephine and Frank Tate were listed as ‘B’ and Crozier was ‘Mu’, presumably meaning Mulatto or a person of mixed White and Black ancestry. Of the 420 other Pacific Beach residents enumerated in the 1910 census, one other entry was listed as ‘B’, 19-year-old Abbey Benjamin, who was from South Carolina. She was a servant in the household of Alfred Pease, an executive of the Folsom Bros. Co., which owned much of Pacific Beach at the time. Everyone else was listed as ‘W’, although 22 had the additional notation on the form that they were ‘Mexican’.

In 1903 F. T. Scripps purchased acre lots 43 and 44 of Pacific Beach, the property between Diamond, Cass and Chalcedony streets and what is now Mission Boulevard, and subdivided it as Ocean Front. Although many lots were sold in the four blocks of the Ocean Front subdivision there were no improvements until Scripps had a house built in 1906 on lots 17 and 18 of block 4, a home that is still standing at 867 Missouri Street. Although Scripps presumably built it as a rental he sold the property to Frank Tate in November 1908 and for more than 20 years it was home to members of the extended Tate family. The 1913 city directory, for example, reported that James Tate and Homer Tate, Frank’s father and brother, lived on ‘Missouri s w cor Bayard’. Homer was a nurseryman, although not for the Scripps but with Cash’s nursery in Pacific Beach.

Frank Tate himself did not live in his house for long. Although city directories from 1908 to 1911 had listed him as cook for F. T. Scripps and living in Pacific Beach, a ‘situation wanted’ ad in the Union in 1912 sought a position in a private family as cook; ‘Good worker, a very fine cook, young colored man. Apply at Scripps bldg. Frank Tate’. In 1914 the city directory listed Tate Frank (Crozier), janitor Scripps Bldg, home 525 C. 525 C Street is the address of the Scripps Building, built by F. T. Scripps in 1907-1908 and still standing at the southwest corner of 6th Avenue downtown. Apparently the janitor position came with living quarters and Frank and Crozier Tate made their home there.

While living downtown, Frank Tate was one of ‘long list of signers’ of a petition to the city council protesting a sign on the front of the Plaza Theatre reading ‘The patronage of white people only solicited’. The petition called the sign ‘out of harmony with the spirit of the best and highest citizenship of this state’, and added that it ‘breeds contempt and prejudice’. As ‘citizens and taxpayers contributing to the upbuilding of the city’ the signers felt ‘unjustly humiliated before the eyes of all classes of citizens’ (there is no indication that the council responded to the petition). Frank Tate was also a baseball player, a member of the San Diego Hornets, which the Evening Tribune noted was a ‘colored outfit’. The sports page of the Union in 1914 included a note that the San Diego Hornets would like a game with any ‘fast’ team at a suburb or in town, ‘notify Frank Tate, Scripps building’. The Hornets were good, defeating the ‘Cycle & Arms nine’ 12 to 5 in August 1914 and claiming the championship of the county. However, the Tribune reported that the ‘darktown heroes’ managed only five hits and made five errors as they were ‘taken down a peg’ in June 1915 by Carmen, 6-3, at Athletic Park.

Frank Tate’s brother Homer died at the age of 29 in 1915 and Frank himself died in 1916, aged 37. His widow, Crozier, made news in 1918 in a Union article about C. Chrisman, a ‘negro fighter’ who was with the ‘Buffaloes’ over in France during World War I. The story included an extract of a letter he had just written to his sister, Mrs. Crozier Tate, of Coronado. Crozier later married Clarence E. Brown and in 1923 C. E. and Crozier Brown sold the property on Missouri Street in Ocean Front to Josephine Tate, Frank’s mother.

In 1911 James Tate’s sister Georgia Pickens had also gone to work for the Scripps as a domestic. The 1912 city directory listed William Edwards, janitor, as residing in Ocean Front, Pacific Beach, presumably meaning the Ocean Front subdivision and presumably in the home owned by Frank Tate, the only home in the subdivision at the time. By 1914 they had married and Mrs. Georgia Edwards was listed as a cook for F. T. Scripps. In the 1918 city directory William Edwards, gardener, Georgia Edwards, laundress, James Tate, gardener, Josephine Tate, cook, Ellen Pickens (James and Georgia’s mother) and Elliott Tate (Ellen’s grandson, James and Georgia’s nephew), were all said to be residing at the ‘south end of Bayard’. This is the same location or address listed in the city directory for F. T. Scripps himself, so the extended family may have been living at Braemar Manor, either under the same roof as the Scripps or in separate buildings on the grounds. The 1920 U. S. Census listed Georgia Edwards, 41, Ellen Pickens, 83, and Elliott Tate, 28, as living in a dwelling on Bayard Street, which could describe the Frank Tate house at the corner of Bayard and Missouri or the Scripps’ property at the foot of Bayard. James and Josephine Tate, both 63, were listed in the same dwelling as the Scripps family. The ‘color or race’ of all five of the Tate relatives was listed in the census as ‘Mu’ (surprisingly, only 57 of the 100 names on the two pages containing their names were ‘W’; 38 others were ‘Jp’ – Japanese).

In 1915 a second house had been built in the Ocean Front subdivision, on lots 31 and 32 of block 3, 936 Diamond Street, and in 1920 it was purchased by Elliott Tate, then working for the city street department. Also in 1921 James and Josephine Tate moved in to the Missouri Street house, joining his mother Ellen Pickens. His sister Georgia Edwards and her husband moved to La Jolla, to Cuvier Street adjacent to the Bishops School.

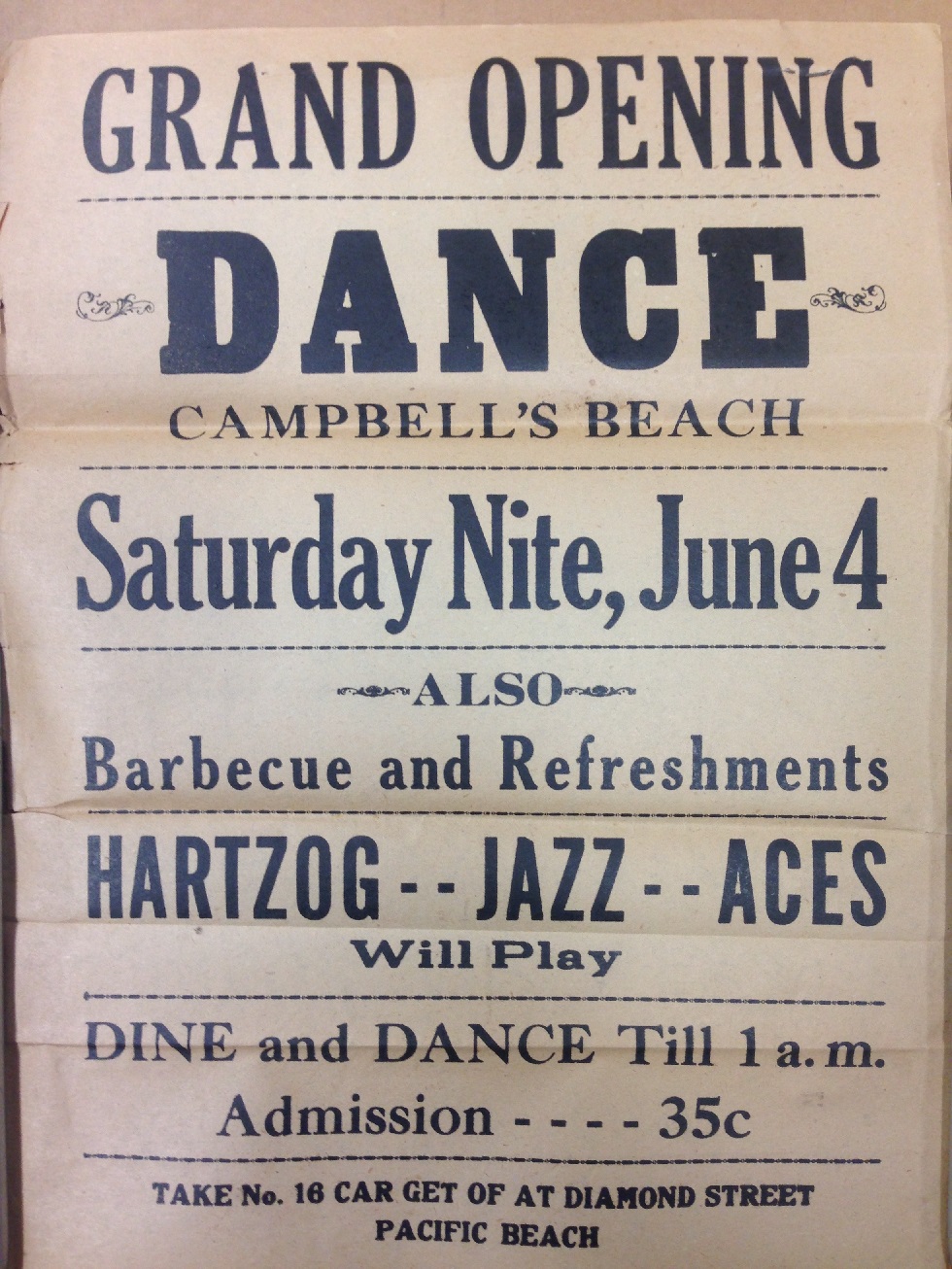

In 1924 Henry Campbell purchased another property in Ocean Front, lots 35 and 36 of block 4, 812 Diamond, and built a home where he lived with his wife Cath and two children. This property was near the corner of Diamond and Allison streets, a block from the beach (Allison has since been renamed Mission Boulevard). Allison was also the route of the San Diego Electric Railway No. 16 fast streetcar line between downtown and La Jolla, opened in 1924, which stopped at Diamond. The Campbell family was also Black, and like Elliott Tate, Henry Campbell was employed by the city street department. In 1925 he received a building permit for a ‘shed’ on his property and in 1926 he petitioned the city council for a license to operate a dance hall on the site. The petition was protested by the Pacific Beach Chamber of Commerce, which asserted that Diamond Street and vicinity was a strictly residential neighborhood and ‘not adapted to jazz band concerts and Charleston contests’. The license was granted anyway and dances ‘for colored people only’ were held at Campbell’s Pavilion or Campbell’s Beach for several years.

Campbell may have held dances on his property even before the pavilion was licensed; on June 20, 1924, the Evening Tribune reported that police led by the local ‘dry’ agent interfered with plans for a ‘negro dance’ near the ocean front at Pacific Beach. Nine ‘negroes’ were arrested and charged with illegal possession of 16 pints of intoxicating liquor. The dance was to have been a celebration of the emancipation of colored residents of Texas on June 19, 1865 – Juneteenth. They were each fined $50 in police court.

The Campbells left Pacific Beach and moved back downtown in 1929. The 1930 census listed nearly 1500 names in Pacific Beach and of these only 9 were identified as ‘Neg’ in the color or race column (there were also 70 ‘Mex’, 50 of whom were located at the brick yard in Rose Canyon, 35 ‘Jp’ and 2 ‘Fil’, Filipinos, the new servants at Braemar Manor). The 9 Black residents included the Elliott Tate family at 936 Diamond, Josephine Tate and Ellen Pickens, then 98 years old, at 867 Missouri, and Jessie Coleman, a 44-year-old female servant working at a home on Los Altos Road. Also included were James and Ella Bass, who lived at 4811 Pendleton Street, then a remote spot at the northeast corner of Pacific Beach overlooking the canyon where Soledad Mountain Road now runs but at the time undeveloped land. The Basses had purchased the property in 1922 and built a board house valued at $600 there in 1925. He had been a janitor at the Spreckels Building downtown but by 1930 was a caretaker for the city play and recreation department. They also raised rabbits on the property.

In 1934 James Bass suffered a leg injury which developed into blood poisoning and required the amputation of the leg. The Pacific Beach chamber of commerce offered to sponsor a series of benefit plays on the school stage in hopes of buying him an artificial leg (the Union reported that Pacific Beach residents were ‘showing a fine and friendly spirit toward James Bass, Negro, who recently had the misfortune to lose a leg’). The benefit plays came up short but friends and fellow playground employees made up the difference and Bass did receive an artificial leg; a photo of the ‘well known colored man’ and his artificial leg appeared in the Union. Ella Bass died in 1937, and James Bass moved away soon after.

James Tate had died in 1927 and Josephine Tate remained in the house at 867 Missouri in Ocean Front until her death in 1931. A White family lived in it for most of the rest of the 1930s but by 1940 it was again occupied by a Black family, Theodore and Elsie Mills and their 3 children. Theodore remarried and moved to the Skyline district about 1965 but Elsie remained at the Missouri Street home into the 1970s.

Elliott Tate and his family also remained in Ocean Front for decades. Ramón Eduardo Ruiz Urueta, later a history professor at UCSD, was born and raised in Pacific Beach during the 1920s and 30s and he devoted a chapter in his 2003 book Memories of a Hyphenated Man to his ‘home town’. He remembered that ‘on almost any day, Mr. Tate, who swept the streets for the city of San Diego, could be seen pushing his two-wheel cart’. The Tates’ daughter Edna was in his grade and ‘took no guff from any of the boys in school’; their son Frank, one of his sister’s classmates, was ‘always courteous’. Mr. Tate and his family were the ‘sole blacks in town’ but as far as he knew no one ‘bothered’ them. ‘Yet by choice or design,’ Dr. Ruiz wrote, ‘the Tates lived on the west end of Diamond Street, far from any neighbors’.

While the Ocean Front subdivision was near its western extremity, Pacific Beach was sparsely settled at the time and the Tate home was actually no farther from its neighbors than many others in the community. The Tate family’s situation had more to do with their association with the Scripps family at Braemar Manor, another home at the west end of the community. F. T. Scripps had originally owned Ocean Front and offered the first house built there, 867 Missouri, to Elliott’s cousin Frank in 1908. In 1920 Elliott Tate bought the second house there, 936 Diamond, half a block away, remaining there until his death in 1966. By then there were few if any vacant lots anywhere in Pacific Beach and he was surrounded by neighbors (including his daughter Edna and her husband Joseph Fields, who lived next door at 944 Diamond into the 1980s). In 1968 the Tate home at 936 Diamond was replaced by an 8-unit Ray Huffman apartment building, appropriately named Tate Manor. The Tate name still identifies the site over a half-century later, although it is now mostly hidden behind a tree.