In February 1930 the San Diego Union reported that fire from an undetermined cause had destroyed the feed storage building of the La Jolla Dairy, located in Bone Canyon, a mile north of Pacific Beach. According to W. C. Rannells, the owner, several tons of feed and 700 bales of hay were lost but the fire departments of La Jolla and Pacific Beach had saved two other buildings adjoining the feed house.

This fire wasn’t the first one that Rannells had experienced. In July 1924, at a time when the dairy was located at the south end of Fay Street in La Jolla next door to the newly opened La Jolla High School, the La Jolla fire department had fought three fires there in a single week. These fires were believed to have been set by a ‘fire bug’ or ‘pyromaniac’ who objected to the operation of the dairy at its location adjacent to the school. This sentiment was apparently shared by many in La Jolla, including Miss Ellen Browning Scripps, who announced that if the board of education would buy the Rannells dairy she would donate enough of her adjoining land to ‘square out’ the property. The board did acquire the dairy and accepted Miss Scripps’ donation and the former dairy site is now the Vikings’ football field. Mr. Rannells reestablished the dairy in what was then called Bone Canyon, north of Pacific Beach.

Bone Canyon was ‘as nice a little green canyon as you’ll ever be surprised to find’, according to the San Diego Union in 1938; ‘There’s a dairy at the head of it, a commercial vegetable patch at the mouth and a goldfish ranch in between’ (the goldfish ranch belonged to Shizur Nakashima and was near where Foothill Boulevard now meets Vickie Drive). The Union columnist added that some fossils once found there gave it the name. A few days later he reprinted a letter from Mrs. Grace Lapham of La Jolla correcting him. She wrote that she didn’t object to having her forebears designated as fossils but that the canyon and surrounding hills was once the property of her grandfather, S. W. Bone, a pioneer San Diego merchant, and for that reason was still known as Bone Canyon.

Samuel W. Bone had been the proprietor of a dry goods store on Fifth Street in San Diego and although he lived downtown he invested in property in Pacific Beach. One of these investments was the east half of Pueblo Lot 1780, 80 acres extending from what is now the northern end of Vickie Drive north to around Camino Ardiente in the La Jolla Alta community and east to about Thunderbird Lane. The canyon that came to bear his name runs through the center of this property. Mr. Bone purchased the property in 1893 and held it until 1912 when it was sold to O. J. Stough. After passing through the hands of Mr. Stough’s attorney Arthur Casebeer it was acquired by William C. Rannells in 1925.

William Rannells was born in 1890 on a ranch in what was then called Linda Vista but would now be on Mira Mesa Boulevard near Black Mountain Road. In 1902 the family moved to Pacific Beach, buying Block 264, the block where the Earl and Birdie Taylor – Pacific Beach Branch Library now stands, but then undeveloped land that the Rannells intended to develop as a ranch. After about a year in Pacific Beach, though, they moved on to La Jolla where William’s father and his older brother Nathan or Nate established the Rannells & Rannells livery service. In 1906 his younger sister Katherine married Fred A. Wetzell and two years later Fred Wetzell and William Rannells started the Wetzell & Rannells dairy in La Jolla. By 1910 William Rannells was sole proprietor of the dairy business, which became known as the La Jolla Dairy. From 1912 to 1914 William and another brother, D. W. Jr., also operated Rannells Brothers Confectionery, fine candies and ice cream.

In 1917 and 1918 the San Diego Union carried ads in the help-wanted section for a man for milking and general dairy work. A married man was preferred. There were 20 cows to milk and a house would be provided; apply to W. C. Rannells, La Jolla. In 1922 the Union reported that Will C. Rannells, a prominent dairyman and one of La Jolla’s pioneers, narrowly escaped death when he was knocked down and gored by a ‘pet’ bull at his dairy in La Jolla. He had owned the bull since it was young and had cared for it himself and considered it harmless. He had gone into its pen to repair a water pipe when the bull leaped on him and forced him against a fence and attempted to trample and gore him. The hired man eventually drove the bull away with a shovel but Rannells suffered a deep cut in his thigh. He was taken away by workers who had started building the new high school next to the dairy. The bull was to be dehorned and have a ring put in its nose. Rannells returned to work and in 1924 the Rannells dairy was among the leaders in ratings of San Diego’s milk supply by the state department of agriculture, earning a rating of 94.0 in the Grade A Raw category.

After moving from Fay Avenue W. C. Rannells continued to operate the dairy in Bone Canyon for over 20 years. In 1930 the Union carried an ad in the livestock wanted section for a young, registered Guernsey bull, 12 to 18 months old, W. C. Rannells, La Jolla. Ads for La Jolla Dairy, the only dairy serving fresh, raw, guaranteed milk twice daily, also ran in the Union. In March 1941 the San Diego County farm bureau’s dairy department met at the W. C. Rannells dairy in Pacific Beach and in 1942 W. C. Rannells was listed as a director of the dairy department of the farm bureau. Also in 1942, he advertised in the Union for an experienced machine milker, married, one understanding feeding, etc., apply Dairy, Pacific Beach, or W. C. Rannells, La Jolla, ph. Glencove 5-3143. Another help wanted ad, for a machine milker, 30 cows, W. C. Rannells, and the Glencove phone number, appeared in 1943.

The war years of the early 1940s had seen tremendous growth in the population of Pacific Beach, including federal housing projects for the thousands of aircraft workers who flooded San Diego to work at Consolidated Aircraft and other wartime industries. One of these housing projects, Los Altos Terrace, was located at the mouth of Bone Canyon with a street, Sylvanite Drive, that followed the course of today’s Vickie Drive and Castle Hills Drive to Windsor Drive. Commercial development was also booming and Pacific Beach was beginning to expand into the Mount Soledad foothills along the road from Lamont Street to the top of the mountain. This road ran across a corner of the Rannells’ land in the hills east of the canyon, making it attractive to real estate speculators. In August 1946 the Rannells sold the portion of their property lying east of the road, the property that one day would be the neighborhood along Parkview Drive, to Arthur and Marion Hansen. A few months later, in October 1946, they sold the remainder of their property, which included the canyon and the dairy (and the road) to Eugene and Thelma DeVoid (in 1949 the DeVoids granted the city an easement and right-of-way for the road, to be dedicated as a public street and named Soledad Road).

The DeVoids financed the purchase of the canyon property with a promissory note for $8,893.22, secured by a chattel mortgage for the livestock at the dairy, which in 1946 included 68 milk cows, 36 Guernsey heifers 6 to 28 months old, 13 Guernsey heifer calves 1 week to 6 months old and 2 registered Guernsey bulls, a total of 119 head of dairy cattle. The DeVoids’ dairy operation in Bone Canyon was apparently a success and their herd grew over time. In 1950 their chattel mortgage for livestock included 1 Jersey, 38 Holstein, and 61 Guernsey cows, 16 heifer calves, 30 heifers, and 2 bulls, one a Holstein and the other Guernsey, a total of 147 head, all branded with an ‘X’ on their right hip. Also mortgaged were dairy equipment like refrigerating units, milking machines, milk aerators, a sterilizer and all other various and sundry equipment of every name and nature used in the operation of the dairy at the DeVoid ranch two miles north of Pacific Beach in a canyon leading north from Sylvanite Drive.

The DeVoids also followed the Rannells’ example by selling off portions of their property along Soledad Road as residential building sites. Three parcels on the west side of the road, overlooking the canyon and the dairy, were sold between 1951 and 1954. In 1957 the DeVoids sold the remainder of their property, the east half of Pueblo Lot 1780 less the four parcels along Soledad Road that had previously been sold, to James M. Banister, a real estate developer, for $109,220.00.

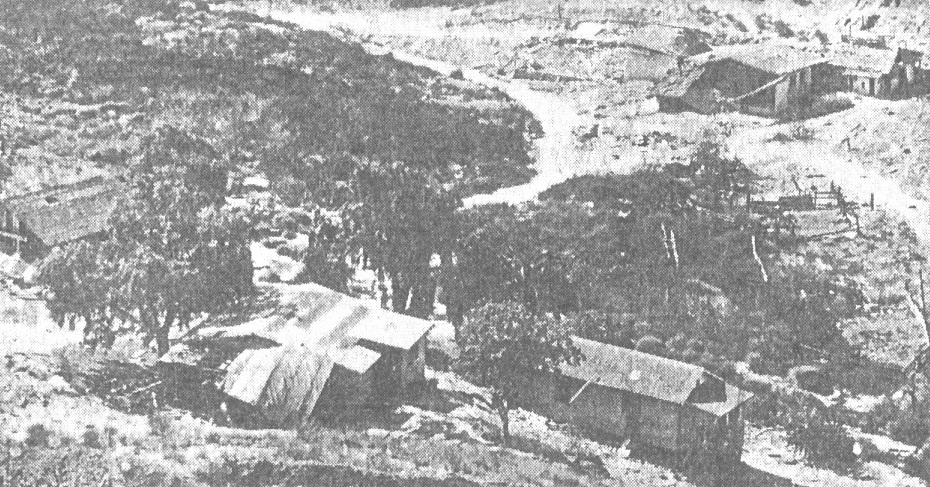

In the early 1960s the Sentinel, a Pacific Beach newspaper, reported on the discovery by four youngsters of what appeared to be an abandoned farmhouse in a canyon north of Pacific Beach. A Sentinel reporter investigating the story called upon ‘oldtimers’ to ‘rack their memories of the old days’. He interviewed Nate Rannells, then 79 and retired as La Jolla’s postmaster, who was sure that the farmhouse was the remains of the old Will Rannells dairy. ‘My brother, Will, built the dairy there in the early winter of 1924. It lies in the canyon to the west of the old Kate Session nursery. It originally comprised three cottages, a milk shed and storage house, cow and horse barns and a corral.’ He added that his brother had 100 cows and a few horses and delivered milk by the dipper-full or by the can to homes and to the trade. The Sentinel reporter noted that the milk-shed and storage house were then still standing, although the roofs had caved in. The corral, one cottage and remains of a horse barn were also still there. The reporter visited a vantage point at the end of Soledad Way and reported that the remains of the Will Rannells dairy could still be seen and was a sight worth seeing. He added that in the distance to the west bulldozers were slashing out sites for new dwellings and soon even the remains of the old Will Rannells dairy would be just a memory.

The property that the DeVoids sold to James Banister was eventually acquired by Techbilt Construction, which had amassed hundreds of acres on the slopes of Mt. Soleded north of Pacific Beach. Techbilt constructed a number of developments around Vickie Drive and Castle Hills Drive in the 1960s and in 1970 began developing the La Jolla Alta developments on the hills on both sides of the canyon. In March 1974 the city council rejected a master plan that called for another 808 homes on a 223-acre site when nearby residents objected to development in the canyon. Techbilt then submitted a scaled-back plan for a 649-unit development that preserved 165 acres for open space, most of it in the canyon, and this plan was accepted in September 1974. The La Jolla Alta community was constructed and Alta La Jolla Drive built across the canyon but most of what was once called Bone Canyon has so far been spared by the bulldozers. The remains of the Rannells and DeVoid dairy, however, are just a memory.