Rancho las Encinitas was granted by the Mexican governor of California to Andres Ybarra in 1842. In 1860 Ybarra sold the rancho to Joseph Mannasse and Marcus Schiller. On January 1, 1864, Mannasse and Schiller were among a group of eight San Diego notables, also including Louis Rose, who recorded claims for mining purposes located around the northeast corner of the rancho. These claims, to be called the Saint David Copper and Silver Lode, were said to be about a mile from the Mannasse home (the ruins of which are now preserved in Carlsbad’s Stagecoach Park) and was further described as about 200 feet north of the Encinitas Silver and Copper Lode, 500 feet N.E. from the ‘place worked’, following the ‘croppings’ (outcroppings?), and 1500 feet from the place worked southwesterly following the croppings.

The Encinitas lode itself was claimed a few days later by Mannasse, Schiller and Rose, along with George Haycock and Joshua Sloane, their notice indicating that the lode was near the ranch of Jos. Mannasse and had been worked a few years earlier; ‘said claim commencing at the old shaft worked in 1857 and running 1200 feet in a South Westerly direction with the croppings’. In March 1866 these individuals filed another claim for the Encinitas Mine, this time commencing at a rock in the center of the ravine and extending in a southerly direction, or in such a direction as to include the lode, for 3000 feet.

Twenty years later, in 1884, Jacob Hoke and William Dougherty filed notice of the location of two mines near the Encinitas ranch, to be known as the Iron Mountain Ledge and the Sulphuret Copper Mine. The Iron Mountain claim was said to be about half a mile from the east corner of the Encinitas ranch and running southerly 1500 feet. The Sulpheret mine ran 750 feet southeasterly and northwesterly from the mouth of a tunnel, which was located 5 chains north of the corner to Sections 32 and 33, Township 12 South, Range 3 West. These coordinates place the mouth of the tunnel a few feet south of the stream known today as Copper Creek, which runs from San Elijo Hills past the mine site and continues along Lone Jack Road to Escondido Creek in Olivenhain. The ravine at the center of Mannasse et al.’s claim for the Encinitas Mine in 1866 was also presumably Copper Creek. The tunnel noted in 1884 may well have been the same as the ‘old shaft’ near the Mannasse ranch which was worked in 1857.

Despite these indications of copper, and possibly silver and even gold, there was apparently little further interest among miners in the area around the northeast corner of the Rancho las Encinitas until the mid-1890s. In April 1896 C. A. Stockton, H. MacKinnon and C. F. Holland filed a location notice in which they claimed 1500 linear feet along the course of a lead, lode or vein of mineral-bearing quartz, and 300 feet in width along each side of the vein, together with all mineral deposits, timber and water thereon. Their claim, the Encinitas Copper Mine No. 1, extended from the center of a creek or gulch in an easterly direction and was marked with monuments at each corner. Although the location notice identified the site as situated in Township 13, Range 4 West, the actual location is in Range 3 West and extends across the line between Townships 12 and 13 South. The creek or gulch again was Copper Creek and the location appears to be the same site as the previous claims which apparently had been worked since 1857. Encinitas Copper Mines No. 2 and No. 3 were later claimed on the west side of the creek.

Within a year of the Stockton-MacKinnon-Holland claim other would-be miners had filed claims in what they called the Encinitas Mining District. In November 1896 William Likens claimed the Encinitas No. 2 West Mine and in December L. F. Hodge claimed the Encinitas No. 2 S. W. Ext. Mine, both west of the Encinitas mine group on the west side of Copper Creek. Likens also claimed the Sentinel Mine, which followed the gulch or canyon in a southerly direction south of the Encinitas mines, and in March 1897 the Veteran Mine, north of the Encinitas mines. Andrew J. Burnett, a San Diego mining engineer, located and claimed the President, Encinitas No. 2 East and Pickett Copper mines in 1896. In December 1896 the San Diego Union reported that MacKinnon and Holland had agreed to sell to Burnett an undivided two-thirds interest in Encinitas Copper Mines No. 1, 2, and 3 for $13,330, or an entire interest for $20,000 on the condition that Burnett would sink a 50-foot shaft and 200 feet of levels (Burnett apparently did not exercise this option).

Prospecting in the vicinity continued and in August 1897 W. W. Rynearson recorded a 1500 by 600 foot quartz claim to be known as the Copper Queen. According to this location notice the Copper Queen adjoined the north line of the Encinitas Grant near the old Grant mine. Rynearson certified that $50 worth of labor had been performed developing the claim by cross cutting and sinking upon the lode or vein at the place of discovery, and in September he also located the Pacific Copper Mine, adjoining the Copper Queen along its west side.

A few days after recording these claims Rynearson sold the Copper Queen and Pacific properties to C. W. Witham and F. J. Kelly for $15,000, and the new owners apparently wasted no time developing the claims. According to the San Diego Union C. W. Witham & Co. had some twenty teams at work hauling building material from San Diego to build a dam some 60 feet high across a gulch to form a reservoir. Quite a number of loads of cement, lumber and other material for the dam were already on the grounds. The Union reported a rich strike of copper ore at the mine, said to be one of the richest discoveries of copper in the west, the assays going high and the walls of the ledge being still out of sight. A depth of twelve feet had been attained and at the bottom the ore gave indications of being very rich. ‘In the opinion of copper miners a find of this character invariably leads to a deposit of pure copper’.

However Witham, and presumably the reports of the mine’s riches, turned out to be a fraud. S. Proctor, a San Diego contractor, later said that Witham had represented himself as a wealthy capitalist and Proctor had introduced him to local businessmen as a man of unlimited credit, but when Witham and Kelly hired Proctor to build the dam at the mine site he soon found that Witham’s checks were not honored. Witham left town, skipping out on his hotel bill, and Proctor tracked him to Pasadena and had him arrested and returned to San Diego where he was jailed on the charge of evading board. He was also sued by several creditors, including Proctor and Frank H. Brooks.

Proctor had placed a lien on the Copper Queen mine to secure payment of his claims against Witham and in February 1898 the Copper Queen was ordered to be sold to satisfy the judgement (a month later, when Witham was again arrested in Pasadena on a charge of horse stealing, the Union noted that he had once been in trouble in San Diego). The Copper Queen claim was sold at public auction at the courthouse door in March 1898 and the property was ‘struck off’ to the plaintiff in the case, Frank Brooks, who submitted the highest bid at $357.77. After a year had passed and no redemption had been made the sheriff conveyed the Copper Queen to Brooks in April 1899.

Another round of locations or re-location in the Encinitas Mining District occurred at the end of 1898. R. O. Butterfield located the Gold Hill Gold and Copper Mine in November 1898 and George W. Magwood located the Copper Gulch Copper Mine in November and the San Diego Copper Mine in December 1898. Also in December 1898, Holland and MacKinnon occupied and claimed a 5 acre site among their Encinitas group of mines for a mill site. In February 1899 they located another claim, Encinitas Copper Mine No. 4, running 750 feet east and 750 feet west along the vein from near the channel of the creek about half a mile downstream from Nos. 1, 2 and 3.

In addition to making a discovery and filing a location notice, miners were required to perform annual assessment work in order to maintain their rights to a claim. Most of the claims in the Encinitas district were apparently not worth the effort but Holland and MacKinnon’s Encinitas group of mines was an exception, at least at first. C. F. Holland’s 1897 ‘affidavit of work on mining claim’ reported that a tunnel 50 feet long, 7 feet high and 4 feet wide had been run and a winze sunk in that tunnel 6 feet square by 6 feet in depth in Encinitas Copper Mine No. 1 (a winze is a vertical or inclined shaft driven downward inside a mine). A frame dwelling house had been erected, the ground graded and ditches dug for draining surface water from Encinitas Copper Mine No. 2 and for Encinitas Copper Mine No. 3 a shaft had been sunk about 4 feet, cuts run to trace the vein and a wagon road graded for transportation to and from the mine. In 1898 Holland reported that the tunnel at mine No. 1 was continued for 15 feet, at mine No. 2 pumps and pipes were replaced in the shaft, water was drained from the shaft and the drift to the north from the bottom of the shaft extended 10 feet, and at mine No. 3 a shaft was sunk 5 feet square to a depth of 7 feet.

The Encinitas copper mines attracted media attention again in September 1899 when the San Diego Union reported a rich discovery of copper, gold and silver ore in an old mine five miles inland from Encinitas. Mining men who had seen it reported that the mine was among the most valuable in the county. The mine was very old, having been opened by some of the earliest white settlers, but the ore giving these returns was entirely new in the mine and did not resemble what had heretofore been taken out nearer the surface. C. F. Holland and H. MacKinnon were the owners, and they now had about 350 feet of tunnel and shaft exposing quite a large body of ore. A new road was being graded to connect with the La Costa railroad station so ore could be sent to Denver.

Holland and MacKinnon incorporated the Encinitas Copper Mining and Smelting Company in November 1899, transferring the Encinitas No. 1, No. 2, No. 3 and No. 4 claims, four full mining claims of 1500 in length by 600 feet in width, and also the Encinitas Mill site of 5 acres to the new company. In its 1899 assessment report, the Encinitas Mining and Smelting Co., reported that the tunnel was continued another 15 feet and the shaft sunk 50 feet in the No. 1 mine and that the drift was continued at least 10 feet and the shaft timbered and hoisting works erected at the No. 2 mine. All the work was performed for the development of the same lode and for the benefit of all their mines.

The San Diego Union traditionally printed a survey of outlying areas of the county in their New Year’s Day editions. The January 1, 1900 report on Encinitas stated that the pretty little village had a neat railway depot, one general store and post office, two hotels and a school house. The population was about 50 and it was one of the most delightful summer seaside resorts on the coast. Another good thing was the opening up in the various copper claims. The Encinitas Copper Mining and Smelting Co. was working the old Encinitas mine but the Copper Queen mine was shut down and in litigation.

Later in January 1900 the Union reported that arrangements had been completed for sinking a shaft 100 feet on the prospect so that the owners would really know what they had in their hole in the ground. In February, MacKinnon and Holland located Encinitas Copper Mine No. 5, north of and adjacent to mine No. 1 and re-located Encinitas Copper Mine No. 3, north of and adjacent to mine No. 2. In March the report was that the hole was down 94 feet and the way that the quality of the ore had been increasing led the projectors to believe that they had a bonanza. The ledge had widened from a trace at the surface to 6 feet at the present depth and there was every indication that it would grow wider. The last assay was nearly 14% copper. At the end of 1900, Frank P. Frary, secretary of the Encinitas Mining and Smelting Co. certified that at least $2000 worth of labor and improvements had been performed on the Encinitas group of mines, known as Encinitas claims Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, consisting of sinking shafts, furnishing materials, powder and fuse, repairing road, deepening a spring on No. 4 and building houses.

In 1900 a new mining company, the Danes Lea Mining Co., appeared on the scene in the Encinitas Mining District. In March 1900, Wilfred C. Harland, the president, filed notices locating the Danes Lea copper mines No. 1 and 2 in the Encinitas district. Later in the year the Danes Lea company also acquired the Copper Queen, Copper Chief, Red Coat, Blue Boy, Red Star and Copper Prince claims. During 1901 the Danes Lea company also bought about 40 acres at the NE corner of the Rancho las Encinitas subdivision, adjacent to the mining district (the former rancho had been subdivided in 1894) and in December 1901 acquired two additional claims from the Encinitas mining company.

News from the Encinitas Mining District had described the location and trading of claims, the development of mines and speculation about the value of the ore, but little or no news about actual production from the mines. In February 1902 the San Diego Union did report that the Danes Lea mine had 2000 tons of copper ore ready for the local smelter as soon as it began to operate and in May the Union reported that Clarence Cole was hauling a carload of ore from the Danes Lea copper mine to Encinitas for shipment to the smelter.

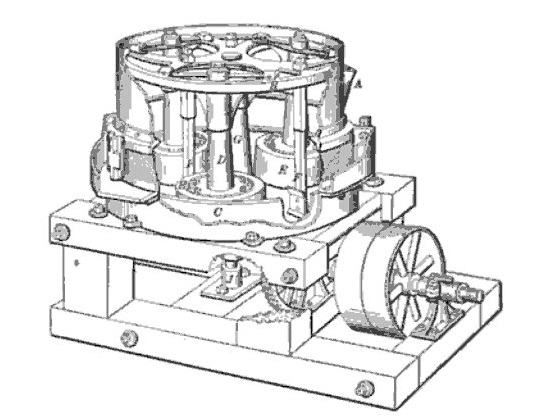

In August 1903 the Evening Tribune reported that the Encinitas Copper Co. had ordered an 80-ton Huntington concentrator. The concentrates would be shipped to San Diego where they would be smelted. There were several hundred tons of ore on the dump but no attempt had yet been made at reduction. Pending arrival of the machinery, roads were being built and other preparations made for doing business on a wholesale plan. The January 1, 1904, Union reported that development work on the ledges of copper-bearing ore at Encinitas had been started a few days earlier by the Encinitas Copper Mining and Smelting Co. which had just erected a mill for concentrating the ore. The mill had a capacity of about 60 tons a day and consisted of a crusher, Huntington mill, concentrating tables, engines and necessary fixings. There were about 1000 tons of ore on the dump running from 1% to 15% copper and an almost unlimited supply in the ground.

The smelter in San Diego was never completed, however, and the cost of transporting the copper concentrate to more distant smelters made continued operations at the Encinitas mines unsustainable. Still, there was occasional news from the Encinitas Mining District over the next few years. In May 1905, the Tribune noted encouraging reports of renewed activity from the Encinitas camp. Sinking would be commenced in the main shaft within a short time and other development work pushed. The company had been developing the project for several years and has spent considerable money. One road which wound through the hills to the railroad cost $3500. One shaft had been sunk to 200 feet where the vein was about 14 feet wide. In October 1907 the Union reported that the Encinitas copper mines were to be taken over and worked by R. J. Coleman, formerly associated with great mining properties in Utah and Mexico with the intention of extensively developing the properties at Encinitas. The mill would be enlarged and all necessary facilities would be provided for economical working.

The New Year’s Day 1908 edition of the San Diego Union included a survey of mining in San Diego County. A section on copper claimed that some unusually extensive copper deposits had been found in the county. The ore was of a high grade and had been discovered in sufficient commercial quantities to justify working. Several years ago a large amount of development was done on the Encinitas copper mines but for some reason work was abandoned and no attempt was made to mine the ore. Recently experienced mining men secured control of the property and work was being done with the view of opening up the mines. Mining men were enthusiastic over the prospects in the Encinitas district, the camp was taking on a new life, and some extensive development could be expected. Both gold and copper could be mined at a profit.

In 1916 D. C. Collier led two automobile loads of mining and money men on a tour of a number of sections between Encinitas and Escondido (Collier was a lawyer and real estate promoter sometimes credited as the creative genius behind San Diego’s Panama-California Exposition of 1915). The mining men brought fine samples of copper ore taken from the neighborhood of the Encinitas mine where the shaft was down to 425 feet and the ore was said to promise good returns. The Ernsting Company’s jewelry store had an interesting display of copper ore taken from a mine operated by the Encinitas Copper Mine Co. The samples showed rich ore and the company expected to be operating a mill in 60 days.

Despite these occasional upbeat reports in the local papers, copper mining in the Encinitas district was ultimately unsuccessful and the Encinitas mines are now almost entirely forgotten (except for a street in a nearby residential neighborhood named Copper Crest Drive). In 1981 Richard Bumann included a photo and a brief mention of the mines in his history of Colony Olivenhain. According to Bumann, the mines consisted of three vertical shafts, two horizontal shafts and a small processing mill. About 5,000 pounds of copper was produced in 1905 but the mines then closed (at about 12 cents a pound in 1905, that amount of copper would have been worth about $600). When World War I caused the price of copper to rise to 27 cents a pound the mines were reopened and about 7,000 pounds were produced between 1915 and 1917 (worth about $1900). An attempt to reactivate the mines in 1925 failed and they have since been blasted shut.

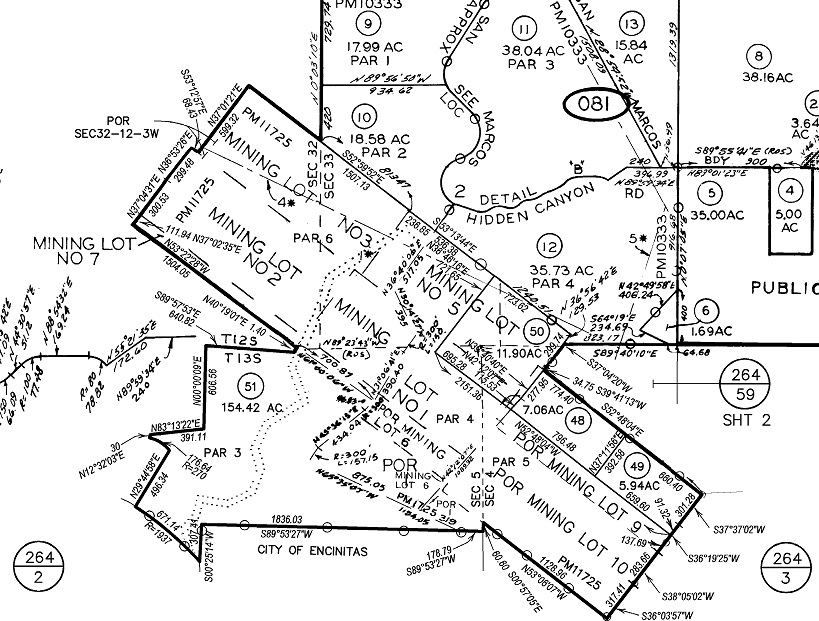

Today most of the area once considered the Encinitas Mining District is still undeveloped and some is preserved within the Rancho La Costa Habitat Conservation Area, open space set aside by developers as mitigation for impacts to natural habitat in their developments. Evidence of mining activity including tailings and location monuments can still be seen on the southwestern slopes of Denk Mountain. At the site of the main mine and mill on Copper Creek there are more tailings and other ruins, including the foundations of the Huntington mill and concentrator. The 1500 by 600-foot claims of the former Encinitas Copper Mines Nos. 1, 2, 3, and 5 at this site are still designated as mining lots on county parcel maps.