In the mid-1920s the ocean-front area of Pacific Beach was still mostly vacant, but it was becoming less isolated. More people were driving automobiles and the Coast Highway between San Diego and Los Angeles, paved since 1919, ran through Pacific Beach on Garnet Avenue and Cass Street. Another branch of the highway, also paved, connected Garnet and Cass to downtown through Mission Beach. For those without cars, the San Diego Electric Railway opened a ‘fast’ streetcar line between San Diego and La Jolla in 1924. The No. 16 streetcar ran through Mission Beach and Pacific Beach over what is now Mission Boulevard.

This increased accessibility caught the attention of out-of-town real estate speculators and in October 1923 the San Diego Union reported that capitalists from Los Angeles and Long Beach had purchased about 350 acres in various areas of Pacific Beach, including more than half of its ocean frontage. The buyers indicated that they intended to spend money liberally to develop their holdings into one of the best residence sections in Southern California. In March 1925 they announced that one of their investments would be a ‘million-dollar pleasure pier’ at Pacific Beach. This development was to be financed and built by Ernest Pickering, who had successfully developed pleasure piers in Santa Monica and Venice (pleasure piers were essentially amusement parks built over the beach). Property values had skyrocketed after construction of the piers in these beach cities and the developers expected a similar return on their investment in Pacific Beach. Construction of the pier in Pacific Beach began in September 1925.

However, Pickering soon withdrew from the project and turned over the development of the Pacific Beach ocean-front to Neil Nettleship, an associate from Santa Monica. Nettleship believed that in order to prosper Pacific Beach would require an entirely new identity, beginning with a new name, San Diego Beach. He continued construction of the pier, which would be the centerpiece of the new San Diego Beach, and also began marketing selected tracts in the nearby ocean-front property that he controlled.

On April 18, 1926, with the pier ‘rapidly assuming form and substance’ at the foot of Garnet Avenue, the public was invited to its ‘formal christening’ as Crystal Pier. The christening of the pier would also be the occasion for the opening sale of the Palisades, scenic ocean-view sites one block from the beach and five blocks north of the new pier. The Palisades consisted of the four blocks lying between Chalcedony, Loring and Bayard streets and the streetcar line on Mission Boulevard, then called Allison Street. According to the official program the events would begin at the Palisades in the morning, with amplified music, a dance orchestra, nail-driving contests and airplane stunt-flying (any purchasers of Palisades home sites would also get a free airplane ride). The actual christening at the unfinished pier, where a mammoth bottle would be crushed by a new electrically-driven pile-driver, would occur in the afternoon. The keynote address would be delivered by Dr. H. K. W. Kumm, geographer, explorer, climatologist, the first white man to explore the last unknown inhabited portion of the globe in Central Africa, and a recent arrival in Pacific Beach, where he was planning to develop a better strain of passion fruit. There would also be a free treasure hunt for children and a surfboard riding exhibition. Despite threatening weather and actual showers Nettleship claimed that a crowd estimated at 10,000 persons attended the christening ceremonies, ‘many sales of property being the consequence’.

Neil Nettleship had formed a partnership with Ben Tye and the Nettleship-Tye Company in turn formed the Crystal Pier Amusement Company, offering stock to investors to raise capital for their improvement projects. Some of these improvements were apparently in place by May, when Miss Palisades, the official representative of San Diego Beach, invited San Diegans to week-end near the pier where the Nettleship-Tye Company had installed a free public beach oven, picnic tables and benches (the invitation in the Union included a photo of Miss Palisades inspecting a pile-driver ‘now busy building Crystal Pier’).

Memorial Day, which even in 1926 was considered the beginning of ‘beach season’, came on Monday, May 31, and the promoters of San Diego Beach planned an elaborate ‘beach warming’ to usher it in. Like the Crystal Pier christening a month earlier, the beach warming would be the occasion for the opening sale of another Palisades tract, Palisades Ocean Front, between the beach and the streetcar line from Chalcedony to Loring streets. In preparation for a busy summer sales season the Nettleship-Tye Company had announced the appointment of the George F. Emery Organization as its general sales agent and the Emery Organization began its sales campaign by inviting all San Diego to help celebrate their taking over for sale the Nettleship-Tye land holdings, including Palisades Ocean Front, the choicest property in San Diego Beach. The beach warming arranged for the next Sunday and Monday would be the greatest free entertainment of its kind in the city’s history. The two-day ‘jollification’ would include music, a free luncheon, contests and souvenirs, and everything was free; you could make your headquarters at the big tent on the Palisades Ocean Front just north of the pier; ‘take No. 16 street car at Third and Broadway, or motor out and we shall park your car free’.

According to the Evening Tribune the first day of the beach warming was a great success; George Emery was quoted as saying that the sale of Palisades Ocean Front was gratifyingly large and he expected a repetition of the success on the second day. The results of that second day were also encouraging, convincing the Emery Organization to inaugurate a series of ‘weekly thrills’, beginning with a ‘tug-of-war’ between a Curtis airplane and a race car to be held at the picturesque Palisades, ‘now being eagerly purchased’. On that occasion the airplane won, but the car’s driver claimed mechanical problems and a ‘momentous second tug-of-war’ was scheduled for the following weekend.

In July the weekly thrills gave way to an ‘Announcement Extraordinary!’. A free lecture by the famed psychologist Brookhart, the idol of men and women who think of tomorrow in life’s calendar, would be given at the Palisades, San Diego Beach – at the big tent on Sunday, August 1. The subject would be ‘San Diego as I See and Analyze It’. The ad explained that Bae Pierre Brookhart, mentalist, philosopher, prophet, would tell you what the future holds in store for San Diego, how it would look 10 years from now. ‘This Great Seer, who sees all and knows all, will unroll the curtain of knowledge for all to read. Be at the Big Tent at 2 P.M. Sunday; you will be astounded at his revelations’. Free transportation would be furnished for those without cars but directions were provided for those who wished to drive out with their own car: ‘take Coast Highway toward La Jolla. After turning to the right at Pacific Beach corner, drive five blocks, look for big tent on left, and drive in’. In 1926 the ‘Coast Highway to La Jolla’ was Garnet Avenue and Cass Street and ‘Pacific Beach corner’ their intersection, where Dunaway Pharmacy was being built at the time. Five blocks north would be Chalcedony Street where the big tent could apparently be seen off to the left, within the Palisades tract (Bae Pierre Brookhart was described as a French-Indian philosopher; his book Sciences of Life as an ‘introductory amalgam of spiritual, esoteric tidbits’)

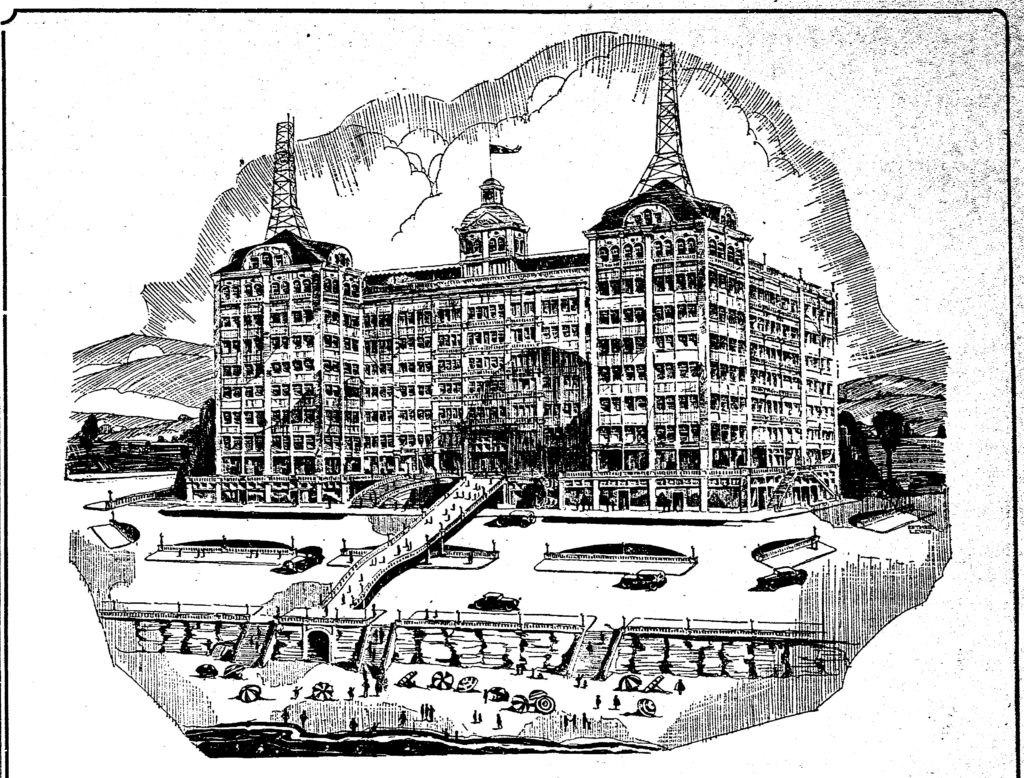

August 1 was also the day that plans were announced for construction of the North Shore Club at the Palisades. It would cost approximately $1,000,000, be six stories high, built of brick and art stone, with a huge arch over the highway, a pedestrian crossing connecting the first floor of the building to the beach and also a tunnel under the highway from the basement to the beach. There would be 100 guest rooms, a roof garden, veranda overlooking the ocean, a mezzanine floor entirely circling the building, and two elevators. Other amenities included a large dining room, main lobby, ballroom, swimming pool, gymnasium, locker rooms, tennis courts, gardens, fountains and a drug store and other concessions on the first floor. According to the San Diego Union, the entire block bounded by Chalcedony and Law streets and Ocean Boulevard, with 270 feet of ocean frontage, had already been purchased from the Geo. F. Emery Organization for $46,600.

The Geo. F. Emery ads in the Tribune repeated this news and announced that the ‘Deal is Closed! A group of lots in Block 79, Palisades, sold to a Beach Club Hotel Syndicate for $46,600, exactly what our printed price list call for – not a thin dime discount’. By September the North Shore Club itself was advertising; its September 3 ad in the Tribune, in advance of Labor Day, said that ‘Next Labor Day you can flee to this wonderful building – and so escape the greatest crowd in the city’s history’. ‘This wonderful building’ was represented by a drawing of a nine-story edifice occupying the entire block, with towers at the corners surmounted by radio masts. A ‘pedestrian overhead promenade’ crossed over the wide boulevard in front of the building and a tunnel opened onto the beach. The accompanying text explained that the tunnel directly connected the beach with the wonderful indoor swimming pool and that the building would include a radio broadcasting station.

The San Diego Union explained that beach clubs had saved the beaches of Los Angeles from overcrowding and cheap commercialism, they bestowed privacy and assured living quarters and breathing space for those who wished to go periodically to the beaches. In effect, they constituted a beach residence on an expenditure of a few hundred dollars, instead of the thousands required for a beach home of one’s own. San Diego would soon have the same beach problems as LA if it did not provide itself with adequate beach clubs. The North Shore Club continued to advertise through September 1926 but interest among potential members was apparently underwhelming and the ads and other references to a beach club at the Palisades soon disappeared from the papers.

In addition to advertisements aimed at potential purchasers, the promoters of Palisades real estate also targeted potential salesmen. An August ad by the Geo. F. Emery Organization in the Tribune was for Creative Salesmen for the Palisades, Top Commissions, Prospects Furnished. ‘Big money for men of ability who can handle high class clients’. Another August ad was for Salesmen With Cars; ‘Palisades going good. Big development to be started will make it go faster. Bus, lunch, lecture. Want efficient salesmen for permanent, high-class business’.

When the relationship between the Geo. F. Emery Organization and the Nettleship-Tye Company ended in October the Nettleship-Tye Company began placing its own classified ads for salesmen in the Tribune (the Emery Organization moved over to the North Shore Highlands subdivision a few blocks to the east of the Palisades, where it arranged an opening sale December 5 with another big tent, bands, refreshments and a free lunch). One Nettleship-Tye ad announced ‘This Is It’; they would start their fall campaign selling Palisades at San Diego Beach and could place a few more eager, earnest salesmen. Another ad said ‘Our men are hitting on high and no knocks. Buyers are buying Palisades at San Diego Beach. There is nothing better to buy and nothing better to sell’. Another said ‘Here’s the deal. Palisades, parlor car buses, solicitors, lunch, lecture and plenty of half page ads. Can use few high class salesmen with cars. More prospects than we can handle. See us quick for big money’. In another, ‘more real honest to goodness prospects than our force can handle – Palisades – San Diego’s hot-spot subdivision. If you have a good car and can sell here’s your permanent job’.

Information about the Palisades could also be found in the real estate sections of the local papers. An October article in the Union featured a view inside the new downtown offices of the Nettleship-Tye Company and of Mr. Tye working at his private desk. Tye claimed that an extensive improvement program would be rushed to completion following the fast sale of Palisades. The improvements would include gas, water, electricity, paved sidewalks, curbs and gutters, but since the improvements would more or less halt traffic in the area the public was urged to inspect the property prior to the improvement program and take advantage of the free dinner served daily at the Palisades Pavilion tent followed by a lecture on the scarcity and desirability of beach frontage.

In an article in the Tribune Mr. Tye commented on the large number of easterners buying homesites in the Palisades; one of the most prominent professional men of Kansas City, a capitalist of Detroit, and a woman very prominent in the social world of New York. ‘The most striking feature of the progress made by San Diego Beach in general and the Palisades in particular the past few months, is the tone of the beach. San Diego Beach will be a high class residential district of San Diego, as already proved by the Braemar development and now by the Palisades’. He continued that ‘It is certainly inspiring that former Pacific Beach, which never did seem to get a start, should now blossom into one of San Diego’s finest dwelling communities, as the swan proceeded from the duckling in the folk-story’. The story included a photo illustrating ‘home building at the Palisades’; the first and only home in the Palisades at the time, one that is still standing at 834 Beryl Street.

Beginning in August 1926 ads for the Palisades had begun to threaten a ‘price advance’; an ad in the Tribune asked ‘Do you want it? You will have to act now, for the present opportunity will be withdrawn in 30 days’ then went on to suggest the free parlor car tour with a delightful lunch and educational lecture at the Palisades and added that the Geo. F. Emery Tours were ‘the talk of the city’. As the year went on the warnings increased; in October it was ‘2nd Call. Only one more week-end until the first Palisade price advance! The buying stampede on November 7th – last day of the old prices – will be so great that you better act now. Let the last-minute throngs rush over your property instead of you’.

Although these warnings of last-minute throngs and a buying stampede matched the rhetoric that the Palisades’ promoters had been proclaiming throughout the 1926 season, the actual results of the Palisades marketing campaign appear more modest. City lot books from that era document the ownership of each lot in each block of every subdivision in the city at noon of the first day of January every year. On January 1, 1927, the close of the year when the Palisades tracts had first been opened for sale, only 6 pairs of lots had changed hands in the original Palisades tract east of the streetcar line (Palisades ‘homesites’ were pairs of the standard 25-foot lots). In the Palisades Ocean Front tract west of the tracks, what had been three Pacific Beach blocks between Law and Loring streets (Blocks 41, 78 and 116) were re-subdivided in August 1926 as Nettleship-Tye Subdivision #1. In this new subdivision, which included the new Crystal and Dixie drives and a new city park, Palisades Park, no property had changed hands in 1926. The only substantial transfers of property had been on Block 79 in the ocean front tract, between Chalcedony and Law streets west of Allison, where on January 1, 1927 J. E. Dodd owned 27 lots; all 10 of the lots along Ocean Front Boulevard, the 16 lots on Chalcedony and one lot on Law Street. J. E. Dodd had represented the North Shore Club and was described as its president, but plans for a 9-story building on this property had not materialized and a year later, on January 1, 1928, all of Dodd’s holdings had reverted to the Crystal Pier Amusement Company (the other property on Law Street in Block 79 had already been in the hands of private owners before 1926 and was not part of the Palisades sales campaign). As for the prominent easterners buying homesites in the Palisades, all but two of the new owners of lots in these tracts had been listed in the San Diego city directory in recent years.

By the end of 1926 the Nettleship-Tye Company seemed to recognize that sales of homesites in the Palisades were lagging, and the company tested the idea of actually building and selling homes on the sites instead. A classified ad appeared in the Houses for Sale column of the San Diego Union in December 1926; ‘Modern bungalow, Palisades, San Diego Beach, half block off car line, beautiful home, large lot, two bedrooms and all modern conveniences, ready to move in, $1000 cash will handle. Will gladly show by appointment. Nettleship-Tye Co.’. An ad for Beach Property in July 1927 offered 1 new 5-room stucco, up-to-the-minute bungalow, beautiful Palisades location, very desirable, right place, easy terms. These ads could only refer to the home at 834 Beryl, the only home in existence in the Palisades at the time. It would eventually be purchased by Fay and Mary La Baume, the first actual residents of the Palisades (Mr. La Baume was a salesman for S. F. Woody, another Pacific Beach realtor).

In 1927 the promoters of the Palisades shifted their sales strategy again. Instead of the ‘half-page ads’ inviting the public to a luncheon and lecture, a Nettleship-Tye Company ‘salesmen wanted’ ad in May 1927 sought experienced subdivision salesmen and closers who know the ‘lunch and lecture method’ for a big summer campaign opening now. ‘We have the system and outside organization to put qualified out-of-town buyers on our beautiful Palisades beach property daily all summer long. City improvements going in now’.

‘City improvements’ such as paved sidewalks, curbs and gutters, had been mentioned before in Palisades ads but in May 1927 these improvements were finally happening. The city council had received a petition to pave the streets in the Palisades district in October 1926. An ordinance establishing the grade of these streets passed in January 1927, a resolution of intention was adopted in February and a resolution ordering work was adopted in March. Bids for the improvements were received in April the contract was awarded to E. Paul Ford. The improvements actually were ‘going in’ in May 1927 and were completed in June and July, dates that are stamped in the concrete sidewalks of the Palisades. In October 1927 the San Diego Beach Chamber of Commerce voted to hold a dance at the Crystal Pier Ballroom to celebrate the completion of paving in the Palisades (the pier, which included a ballroom over the water, had also been completed and opened in July 1927, but it turned out that the pilings had not been properly treated and were soon attacked by marine borers; it was condemned and closed in 1928, and not rebuilt until 1934).

Lot sales in the Palisades continued at about the same pace in 1927. Eight more homesites, or pairs of lots, had new owners on January 1, 1928, in the Palisades tract east of the streetcar line (including the homesite under the only actual home in the tract, which had been purchased by the La Baumes). West of the tracks, no lots had been sold yet in the Nettleship-Tye #1 subdivision and in Block 79 the 27 lots owned by J. E. Dodd for the North Shore Club at the beginning of 1927 had returned to the ownership of the Crystal Pier Amusement Company by 1928. With sales of lots lagging, in April 1928 the promoters changed direction again and advertised their ocean frontage for lease; ‘long term lease at low rental on an entire block of ocean front property at Pacific Beach, on the car line and suitable for beach cottages’.

The developers also revisited to the idea of actually building and selling homes instead of homesites in the Palisades. In April 1928 building permits were issued to the Nettleship-Tye Company for houses at 820, 827 and 838 Wilbur Street. Later that year the house at 820 Wilbur was one of four homes around the city that were featured in an educational exhibit by ‘Home Beautiful’ expert Rosalie Ann Hager. An article in the Union explained that this home in the lovely Palisades district overlooking the sea was built by the Nettleship-Tye Company and loaned to Miss Hager for the occasion. It was a medium-priced home of pure Spanish design with five rooms besides a large breakfast nook. There was a photo of the exterior of the home and a detailed description of its interior, including the color scheme, draperies, floor coverings and furniture, which Miss Hager had planned for a young couple. The Union reported that nearly 10,000 guests attended the week-long open house for these ‘Home Beautiful’ residences.

Despite the talk of buying stampedes and throngs of eager purchasers, only about 10 percent of the lots in the Palisades had actually been sold by 1928. The three homes built on Wilbur and the La Baume home on Beryl were the only actual residences and the La Baumes were the only residents. San Diego was still a small town in the 1920s and Pacific Beach was a remote suburb, even if it was served by a highway and a streetcar line. Potential buyers could also choose from other nearby subdivisions including Crown Point, Braemar, Pacific Pines and North Shore Highlands, all of which also opened in 1926 (and also had disappointing sales). Real estate sales would not improve for many years; the Great Depression which began in 1929 and lasted through the 1930s reduced economic activity of all kinds and in Pacific Beach the Mattoon Act further depressed the market by pyramiding ever-higher assessments on property owners to pay for construction of the causeway across Mission Bay.

The Nettleship-Tye company closed its branch office in the Crystal Pier building in 1930 and the partnership itself had ended by 1931 when Nettleship had Tye charged with grand theft for allegedly depositing the proceeds of lot sales into his own account instead of the company’s (the indictment was dismissed and the judge indicated that whatever difference the partners had should be settled in civil litigation). By 1940 only five more residences had been built in the Palisades, all in the section east of Mission Boulevard (which had been paved in 1928 and renamed in 1929) and there was still no home construction west of Mission Boulevard in the Palisades Ocean Front tract.

All of this changed in the 1940s as Consolidated Aircraft and other defense industries ramped up production during the war years and attracted tens of thousands of workers to San Diego. Many of these workers were first housed in temporary government housing projects in Pacific Beach, including the Los Altos Terrace project just two blocks from the Palisades. When the Federal Housing Authority made loans available for defense workers to buy commercially-built homes, builders attempting to meet the demand were attracted to tracts like the Palisades that had already been improved with paved streets, sidewalks and utilities but were still mostly vacant. This home-building surge continued even after the war and by the early 1950s there were few vacant lots to be found in any residential area of Pacific Beach, including the Palisades.