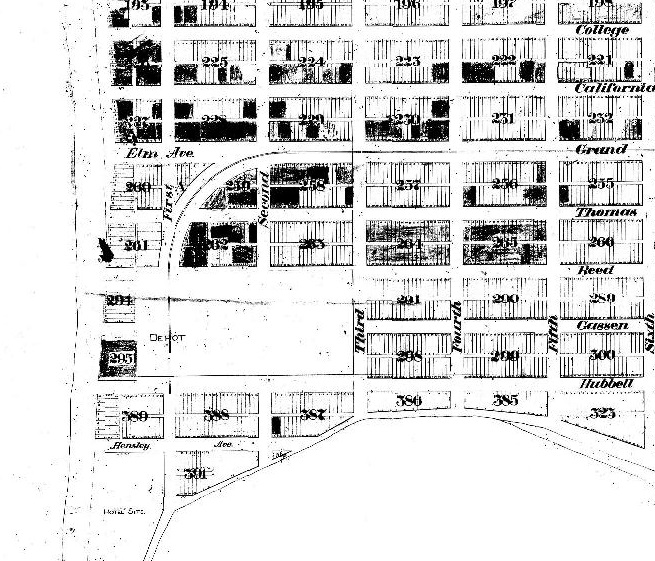

On the original map of the Pacific Beach subdivision from October 1887 a railroad line from downtown San Diego ran down Grand Avenue to a depot located between the Pacific Ocean and False (Mission) Bay near the southwest corner of the community. The property allocated for the depot occupied about four blocks between Reed and Hubbell avenues and from west of First Street to Third Street (Hubbell Avenue has become Pacific Beach Drive, First Street is now Mission Boulevard and the other numbered streets have been renamed Bayard, Cass, Dawes, etc). On the map the depot property was surrounded by residential blocks, most consisting of 40 lots.

In an amended map recorded in 1894, the Pacific Beach Company consolidated most of the residential blocks south of Reed Avenue into ‘acre lots’ intended for agricultural use and eliminated Gassen and Hubbell avenues. The blocks east of the depot property became Acre Lot 69; south of the depot Block 389 and half of Block 387 remained, while the rest became acre lots 70 and 71. The Pacific Beach Company had originally purchased the 40 acres south of the depot property from James Poiser, a sheep rancher, and Poiser still retained a plot on the bay shore known as ‘Poisers 1 Acre’. The railroad line had been extended up the coast to La Jolla but an engine house for the line’s locomotives remained in a smaller ‘depot grounds’ on the former depot property. The remainder of the property became known as the ‘unnumbered lots east of the depot grounds’.

In December 1899 Poisers 1 Acre was sold to Frederick Tudor (F. T.) Scripps, brother of the newspaper tycoon E. W. Scripps and half-brother of Ellen Browning Scripps, the La Jolla philanthropist. In August 1900 Scripps also bought Acre Lot 71, 4.9 acres located just to the north of Poisers 1 Acre and separated from it on the map by the former Hensley Avenue. Scripps petitioned the city council to close Hensley Avenue, which then apparently reverted to Scripps and gave him possession of an approximately 6-acre parcel between the bay and the depot property. By the end of 1901 he and his wife Emma had built a palatial bayfront home surrounded by elaborate landscaping that they called Braemar Manor.

F. T. Scripps also acquired and developed other property in Pacific Beach. In 1903 he purchased acre lots 43 and 44, between Diamond, Allison (now Mission Boulevard), Chalcedony and Cass Streets and subdivided it as Ocean Front Addition. Closer to home, he extended his bayside property another block east by purchasing Acre Lot 70 and Block 387 (except for lots 33 and 34, which the Pacific Beach Company had sold to Richard Poiser, James’ son, in 1889, and were then owned by E. R. Higbee). In 1904 he added another 1 1/3 acres of land west of and adjoining the original Poisers 1 Acre property, between the bay shore and Acre Lot 71. He also purchased the ‘unnumbered lots east of the Depot Grounds’ and Acre Lot 69, extending his holdings north to Reed Avenue and east to Dawes Street.

In 1907 Scripps consolidated his holdings into the Braemar subdivision, five residential blocks east of Bayard Street and Lot A, west of Bayard Street and south of Pacific Avenue (now Pacific Beach Drive), where his home and gardens were located. The residential blocks were intended for sale but despite the apparent attractions of the beach and bay and the convenience of the nearby Braemar station on the railroad line (on Grand Avenue at Bayard), buyers showed little interest in this remote corner of Pacific Beach. One buyer did purchase 4 adjacent lots on Oliver Street in 1908 and another 4 buyers purchased a total of 8 lots in 1909 but few additional lots were sold and only one home was built in the Braemar subdivision before the 1920s (in 1912, still standing at 932 Oliver Avenue). In 1917 Scripps also subdivided the property in the unnumbered lots, north of Pacific and west of Bayard, as First Addition to Braemar. Only two lots were sold there over the ensuing decade but Scripps had homes built on three lots he owned facing Bayard between Reed and Oliver avenues, presumably as rentals.

In 1924 the San Diego Electric Railway opened a fast streetcar line between downtown and La Jolla via Mission Beach that ran through Pacific Beach over what became Mission Boulevard. The coast highway from San Diego to Los Angeles also passed through Pacific Beach and had been paved in 1919. The western branch of the coast highway entered Pacific Beach from Mission Beach then followed Pacific Avenue and Cass Street to Garnet Avenue, passing through the heart of the Braemar subdivision. At Garnet it was joined by the eastern branch and continued on Cass to Turquoise Street and La Jolla Boulevard on its way north. By the mid-1920s thousands of motorists were traveling on the coast highway daily and real estate speculators began developing the corner of Cass and Garnet as the new business center of Pacific Beach. Crystal Pier was developed as a tourist attraction in 1925 and a number of new housing tracts were planned, including the Palisades, North Shore Highlands, Pacific Pines and Crown Point.

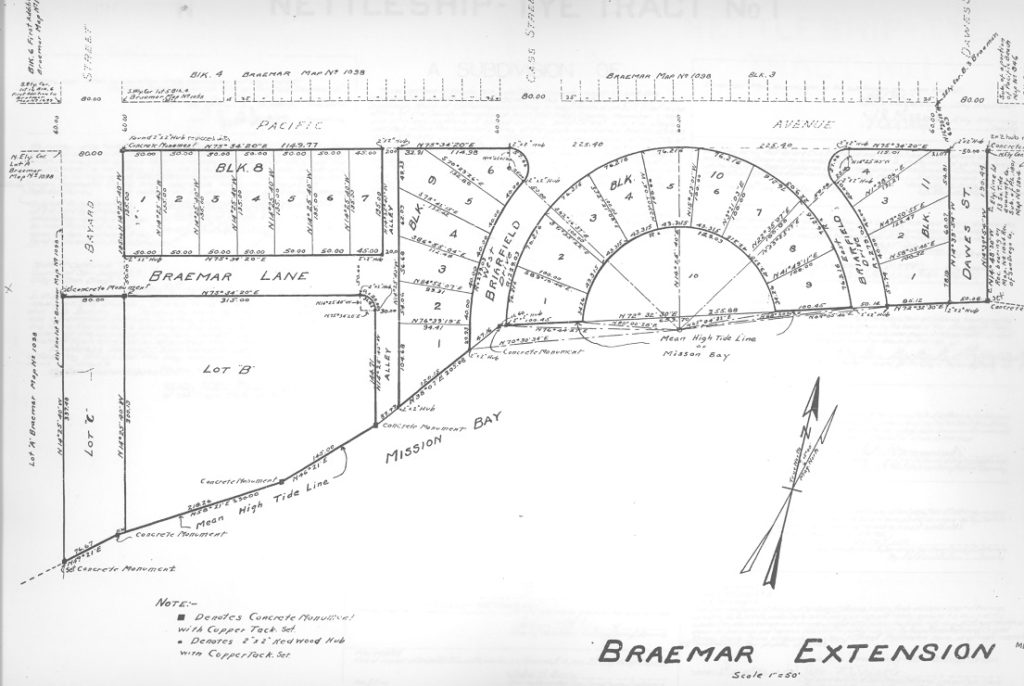

F. T. Scripps also saw opportunity in the renewed interest in Pacific Beach real estate. In May 1926 he persuaded the Common Council to close the southernmost half-block of Bayard Street and in June filed a subdivision map for Braemar Extension, incorporating the closed street along with that portion of the Braemar subdivision east of Bayard and south of Pacific and newly acquired property south of Pacific extending another block east to Dawes Street (Scripps also finally bought the two lots in the former Block 387 that had not been included in the 1907 Braemar subdivision and included them in the 1926 Braemar Extension). Braemar Lane was moved a half-block north on the map and a new city street, Briarfield Drive, was shown to the east of Lot B of the new subdivision. Lot B, east of the closed portion of Bayard Street and south of the new Braemar Lane, was divided into three parcels fronting on Mission Bay which were distributed to three of the four Scripps children (F. Tudor, Jr., the youngest, was only 18 at the time and apparently not eligible). Thomas Scripps, the oldest, received the western-most lot, separated from his parents’ property by the closed portion of Bayard Street, and his own bayside home was completed by the end of the year. The closed portion of Bayard Street was designated Lot C of Braemar Extension and effectively became a private drive into the grounds of the Scripps compound.

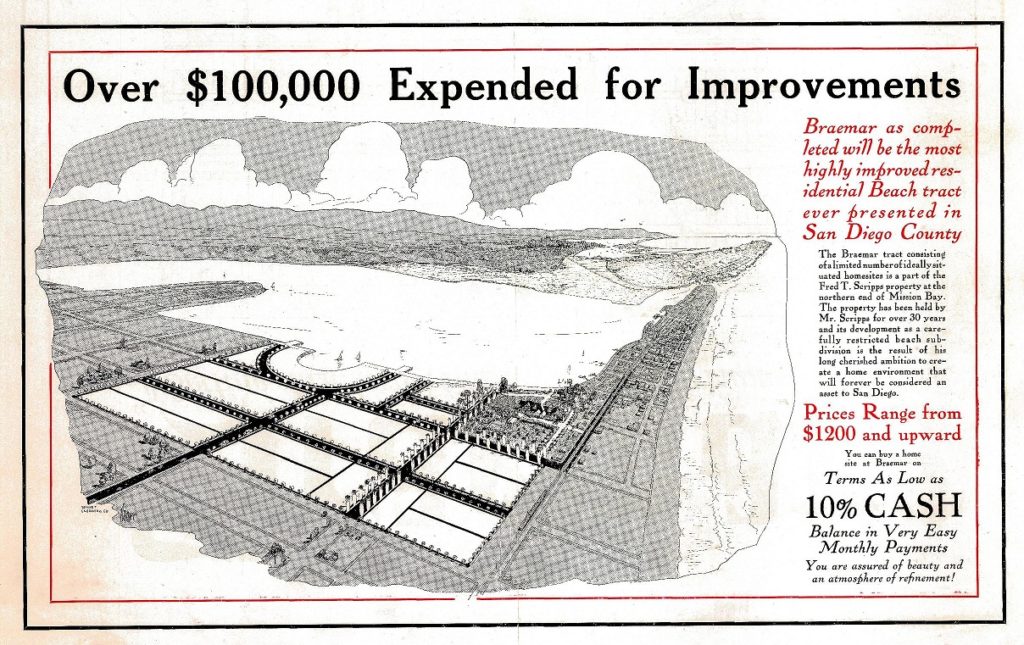

The Braemar Extension subdivision map specifically excepted any portions thereof lying below the line of mean high tide, but Scripps also obtained a 50-year lease from the Board of State Harbor Commissioners for use of the tidelands extending from the mean high tide mark offshore to a proposed seawall (which was never built). Scripps then reportedly spent over $100,000 in improvements for the Braemar, First Addition to Braemar and Braemar Extension subdivisions, including concrete streets, alleys, sidewalks and curbs, and even a cove for boating (Briarfield Cove, surrounded by Briarfield Drive).

On the day of its opening in July 1926 the San Diego Union proclaimed that the Braemar tract would be one of the most highly developed residential beach properties yet presented; ‘All public utilities, including gas, electricity, water and a complete sewer system are in and ready for connection’. The development was also ‘carefully restricted’; no homes could be built which cost less than a minimum value, which ranged from $3500 to $7500 depending on the value of the lot. There were uniform set-back restrictions and restrictions against flats or apartment houses, and also race restrictions:

No part of said property, or any building thereon, shall ever be used or occupied by any person not of the Caucasian race, either as owner, lessee, licensee, or in any capacity other than of a servant or employee of the occupant nor shall said property ever by mortgaged, sold or transferred to any person not of the Caucasian race.

A sales poster featuring a birds-eye view of Braemar emphasized its location on the bay and a block from the ocean and showed the western branch of the coast highway running through the tract before continuing through Mission Beach to downtown San Diego. A streetcar is shown passing by on the fast electric line from San Diego to La Jolla. The trees lining the streets in this view also actually existed and many are still growing.

In 1926 Scripps also undertook a major renovation of Braemar Manor which enlarged it and changed its exterior appearance to the then-popular English cottage style. This style also inspired the architecture of some of the first homes in the Braemar subdivision. An ad in the San Diego Union in September 1926 invited the public to inspect the charming English home at the new Braemar tract built by A. M. Southard Co. (still standing at the corner of Oliver and Cass streets). Another Southard ad in 1927 showed the English cottage at 4225 Bayard, designed and built for Mr. F. T. Scripps.

Not all the new homes built in Braemar were English cottage style; an ad by builder Everett H. Bickley showed the two-story Spanish-style home at 4121 Bayard as it appeared in 1927. A set of ‘artistic entrance gates’ designed by Frank W. Stevenson and said to be faithful reproductions of the stately entrances to be seen on the picturesque old estates in England marked the entrance to Braemar on the coast highway. The tall stone gateposts with the letter ‘B’ flanking Cass Street at Reed Avenue no longer exist but the shorter sections beyond the sidewalks are still there, the one on the west side incorporated into the resident’s brick wall.

In October 1926 selling agents Barney & Rife warned of a ‘price advance’ and then a few days later advertised that they were extending the deadline by a few days because the warning had brought them so many eager customers. In November they warned again that with the steady demand for the property there was a probability of the tract being entirely sold out with the next few weeks. In reality the Braemar tract was competing for buyers with the other new developments in Pacific Beach and all were experiencing disappointing initial sales. By 1928 only 50 of the 147 lots in the Braemar tract had been sold and there were only 8 new residences, all but one of which were on property actually owned by Scripps or Barney & Rife. Two of these residences were not even new but were relocated there from other Scripps properties. The house at 953 Reed had once been E. R. Higbee’s home in lots 33 and 34 of Block 387, built about 1896. Scripps finally obtained these lots in 1925 and incorporated the block into Lot B of Braemar Extension, and the existing house was moved to make room for a home for his son Thomas. The house at 961 Reed had probably been one of the three rental houses built by Scripps in the First Addition to Braemar in 1917. In the First Addition only one additional lot had been sold by 1928 and the only improvements were the two remaining rental homes. Only 5 lots had been sold to the public in Braemar Extension and none had been improved other than the home of Thomas Scripps in Lot B.

Real estate activity in Pacific Beach continued to be slow throughout the 1930s, due to in part to the great depression and the impact of the Mattoon Act, which greatly increased property taxes to pay for civic improvements like the causeway across Mission Bay, and in the Braemar subdivisions only a few more homes had been built by 1940. However, in 1935 Consolidated Aircraft had opened a manufacturing plant on the Pacific Highway near the San Diego airport and in 1940 began production of the B-24 Liberator bomber. Demand for the bombers increased as World War II began in Europe and the United States began preparing for war, and Consolidated expanded production in other factories built along Pacific Highway. Tens of thousands of aircraft workers flooded into San Diego to man the assembly lines and real estate developers recognized that these workers would require housing in areas accessible to the factories, like Pacific Beach, and especially in areas that already had paved streets, sidewalks and other improvements, like the Braemar tract.

F. Tudor Scripps Jr., the youngest son of F. T. and Emma Scripps, teamed up with builder Larry Imig and their contracting and building company commissioned a number of low-cost homes which qualified for FHA Title 6 financing. Other builders also joined the construction boom and the number of homes in Braemar had more than doubled by 1942 and doubled again by 1945, to more than 50. By 1953 the number of homes had doubled again and the tract was fully built out. Martha Farnum elementary school opened across Reed Avenue from the Braemar entrance gates to accommodate the surge of children growing up in Braemar and the surrounding neighborhoods.

F. T. Scripps had died in 1936 but Emma Scripps continued to live at Braemar Manor until her death in 1954. In 1959 Braemar Manor was razed and the Catamaran Hotel built on what had been Lot A of the Braemar subdivision. One room from the Scripps’ home, the English cottage-style dining and music room, was saved from destruction and moved across town to Rose Creek. Now known as the Rose Creek Cottage it is available for weddings and other special events.

In 1926 Scripps and other landowners with bay front properties had been granted a 50-year lease to the Mission Bay tidelands beyond the high water mark where their properties actually ended. Many of the leaseholders had built piers, docks, fences and other improvements on this leased land, which had become known as Crescent Beach. The leases had stipulated that on termination of the lease the lessee would remove all improvements, but when the leases did expire in May 1976 many of the Crescent Beach leaseholders, some of the wealthiest and most influential people in San Diego, refused to comply with the terms of the lease. The city had the offending docks and piers demolished and sand dredged from the bottom of the bay was deposited on shore to extend the beach beyond the former high water mark. A paved bayside walk was built on the reclaimed land outside of the private property lines so that the actual beachfront is open and accessible to the public. Residents on Briarfield Drive in the Braemar Extension subdivision still have private beaches on Briarfield Cove, which remained open to the bay under a bridge on the bayside walk. Only the Catamaran Hotel still has a pier extending into Mission Bay.