The San Diego area was first visited by Spanish explorers in 1542, when Juan Rodriquez Cabrillo sailed into San Diego Bay (and named it San Miguel). The next visit by explorers occurred in 1602, when Sebastian Vizcaino anchored in the bay, which he renamed San Diego. A survey party sent ashore on Point Loma reported that they could also see another good port to the north. Ensign Sebastian Melendes was sent aboard a frigate to sound, map and explore this port, and reported that they had entered it and that it was a good port, although its entrance had a depth of only about two fathoms. Ensign Melendes and his crew thus became the first to sail in Mission Bay.

Vizcaino did not name Mission Bay; the map accompanying his report described it as ‘ensenada de baxa entrada’ or bay of shallow entrance. The bay later appeared on a map drawn up in 1782 by Juan Pantoja, a pilot in a Spanish fleet which had visited San Diego. The Pantoja map named it Puerto Falso, which, after the American takeover of San Diego in 1846, became False Bay.

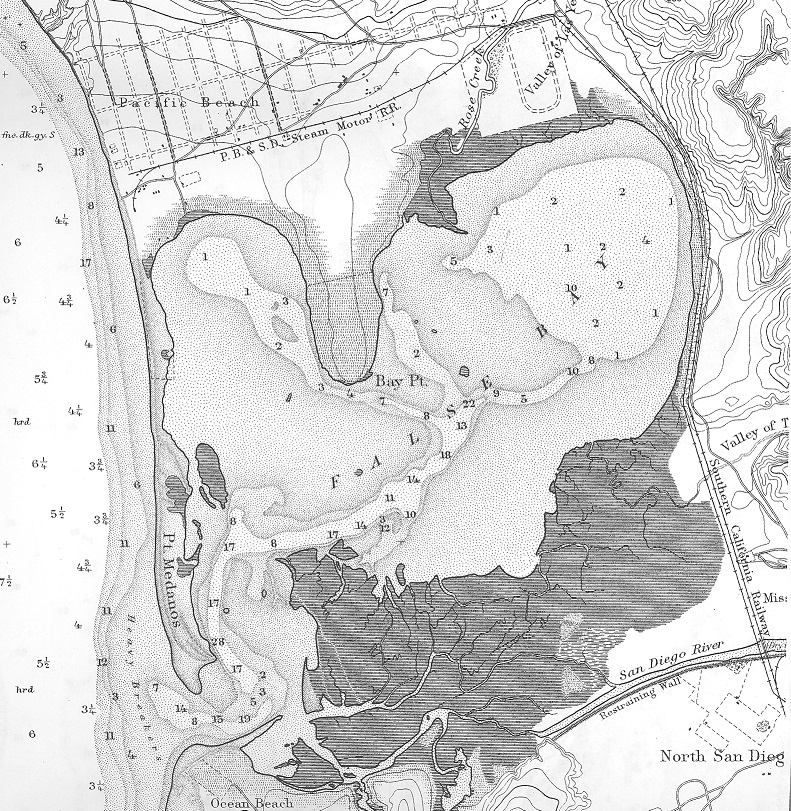

The basic topography of False Bay was shown on a nautical chart from 1891. It was protected from the ocean by a narrow peninsula called Pt. Medanos. A channel between Pt. Medanos and Ocean Beach connected the bay with the ocean and continued diagonally across most of the width of the bay. Outside of this channel, the bay was extremely shallow, often dry at low tide. Rose Creek, Tecolote Creek and the San Diego River all flowed into False Bay. The river had been diverted into False Bay by a dike or restraining wall built in 1853 to prevent its silt and debris from building up in San Diego Bay. The silt and debris built up ‘mud flats’ along the south shore of False Bay instead.

In 1769 the Spanish had established a presidio or military post on the bluffs near the mouth of the San Diego River. Padres accompanying the expedition also established the first of the California missions near the presidio, and a few years later moved it upstream to the present location of Mission San Diego de Alcala, in what became known as Mission Valley. In 1887 the San Diego Union announced a new city to be built at False Bay called Pacific Beach, which would have an institution of learning second to none, the San Diego College of Letters. The college was the idea of Harr Wagner, editor of The Golden Era, a San Diego literary magazine, to which he had recruited Rose Hartwick Thorpe, author of Curfew Must Not Ring Tonight, perhaps the best-known poem of the era. Mrs. Thorpe later contended that in conversations with Wagner the name Mission Bay had come to one or the other of them as more fitting than False Bay for the estuary at the mouth of Mission Valley. That name was picked up by the local press and when the San Diego Union reported an excursion on the newly completed railroad line to Pacific Beach in April 1888, the ride was ‘around the eastern shore of Mission Bay’. Another Union article in August 1888 predicted that around False Bay, ‘or Mission Bay, as it is now called’ there would soon be a large settlement radiating from Pacific Beach, Morena and Ocean Beach.

Mrs. Thorpe popularized the new name for the bay with a poem in the August 1888 edition of The Golden Era:

Mission Bay

Beyond the bay the city lies,

White-walled beneath the azure skies,

So far remote, no sounds of it

Across the peaceful waters flit.

I watch its gleaming lights flash out,

When twilight girds herself about

With ocean damps. When her dusk hair

Wide-spread fills all the salt sea air,

And her slow feet,

Among the fragrant hillside shrubs,

Stirs odors sweet.Fair Mission bay,

Now blue, now gray,

Now flushed by sunset’s after glow,

Thy rose hues take the tint of fawn

At dawn of dusk and dusk of dawn.

God’s placid mirror. Heaven crowned,

Framed in the brown hills circling round,

Not envious that thy sister can

More fully meet the needs of man,

Nor jealous that her broader breast

is sacrificed at man’s request,

While in the shelter of her arm

The storm-tossed resteth safe from harm.This thy grand mission, Mission Bay –

To smile serene through blue or gray;

To take whatever God has sent,

And teach mankind a full content.

Despite the growing acceptance of the new name, False Bay did not officially become Mission Bay until 1915, and the two names continued to be used interchangeably for decades. Harr Wagner himself described Pacific Beach in January 1891 as a large plateau sloping southward to False Bay and west to the Pacific Ocean. As late as 1929 the ZLAC Rowing Club announced in the Union that their annual fete would be held at Brae Mar, the charming home of F. T. Scripps at the head of False Bay (Brae Mar was demolished in 1959 and replaced with the Catamaran Resort Hotel, but the nearby ZLAC clubhouse, on the shore of Mission Bay, is still standing).

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, False Bay or Mission Bay was mostly visited by sportsmen; its shallow waters and marshy shores were ideal duck habitat and fish could be found in the deeper channel leading to the ocean. In 1908 the Union reported that the just completed Bay View apartment house situated on the shore of False Bay was proving deservedly popular with sportsmen and duck hunters, and that one party had bagged 33 ducks in a couple of hours (not all duck hunters were sportsmen, however; in 1891 there were complaints that some professional hunters were slaughtering ducks using a regular mountain howitzer in a skiff, and sometimes killing a hundred at a shot).

Fishing was also a popular attraction, but the quality of fishing depending on variable natural conditions. The Evening Tribune reported in 1901 that False Bay was invested with seals that had eaten up all the fish, or at least enough of them to make fishing poor. In 1902 the fishermen said the water was too clear and the fish had all deserted False Bay. In 1903, by contrast, the recent rains had made the fishing in False Bay very good, and that kept anglers busy when not employed in the orchards. Some of the fish stories were memorable. While fishing in False Bay in 1901 Rufus Martin hooked a shark of such dimensions that it broke his pole after he had played it for an hour and a half. Lloyd Overshiner landed with hook and line a stingray over five feet long and four feet wide and after landing it he had to kill it with a shotgun.

In addition to fish, sharks and seals, whales occasionally entered Mission Bay. The Union reported in 1904 that two ‘monster whales’, one at least 30 feet long, furnished a spectacle just a few feet off the shoreline at the foot of Eleventh (Lamont) Street. They were first discovered by W. A. Pike, who, being a sportsman returning from a shooting jaunt, promptly emptied both barrels of his gun into the side of one of them, which responded by spouting high into the air.

Swimming and boating in the bay were also popular. In 1890, the Union reported that the fifty students of the College of Letters were adding swimming to their accomplishments. Material for a bath-house and pier were furnished by the college and the students accomplished the building in a little sand beach cove on Mission Bay, below the college (near the foot of today’s Kendall Street). Students and faculty had swimming lessons two afternoons each week. By 1898 the Union reported that Mission Bay was a favorite bathing place; every day saw more or less of a crowd and on Saturdays about forty, old and young, took a swim. In 1906 an ad for Folsom Bros. Co., which owned much of Pacific Beach, stated that as an indication of how residents and visitors enjoyed Mission Bay it was not unusual to see from 40 to 60 people taking a dip at the Fortuna bath house and wharf.

In June 1906 the Union reported that nature had caused the waters of Mission Bay to present a wonderful sight when darkness set in. Thousands of tiny electric eels, fireflies and glow-worms appeared to be creeping over the smooth surface. This effect was said to be produced by the warm night breeze, greatly ruffling the water, which is filled with ‘microscopical luminous animalculae’. An occasional clump of reeds and other submarine growths could be passed over, showing distinct and white, with fish of opal fire gliding in and out; ‘From under the bow of the boat light spreads as though a lantern were fastened there, and near the cliff, where it is still as a pond, the oars ignite a six-foot circle of bluish-white light’. Many parties from the newly-opened Hotel Balboa and elsewhere in the suburb had been out enjoying this magnificent spectacle.

In 1914 the Mission Beach Company announced a new residential and amusement tract on the peninsula between the Pacific Ocean and Mission Bay. Development would begin with a bridge built across the entrance to the bay by the Bayshore Railroad to carry a trolley line and an automobile boulevard between Ocean Beach and Mission Beach. The bridge was completed in 1915 and in 1916 the trolley line had reached Redondo Court in North Mission Beach, where J. M. Asher, a Pacific Beach real estate operator, was contracted to develop a tent city to accommodate tourists. Asher’s tent city, which included a bath house, swimming pool and pier into Mission Bay, was completed by October 1916.

In 1923 the Mission Beach Company and the San Diego Electric Railway Company jointly announced a project to build an amusement center in South Mission Beach. The amusement center would provide a choice of swimming in the surf, in a large indoor swimming pool, or in the still water of the bay, where a cove called Bonita Bay had been dredged on the inside of the Mission Beach peninsula. The rail company would absorb the Bayshore Railroad company and connect its line to downtown San Diego over a causeway through the southern portion of the bay and across the adjacent mud flats. Bonita Bay and the electric railway line thus became the first substantial dredge and fill projects in Mission Bay.

In 1927 residents of north shore communities petitioned the city to build a causeway across the bay from the southern tip of Crown Point to provide a more direct route auto route between the north shore and downtown. The plan was to dredge material from the bottom of the bay to create a 2100-foot section of fill connected to Crown Point on the north and the mud flats on the south with bridges built on concrete piles. The section of causeway across the mud flats would also be raised with fill from the bay and include a 72-foot culvert over a low point on the bay shore. The dredging operation would have the added benefit of improving boating conditions on the bay; there were already channels along the east side of Mission Beach and the west side of Crown Point, but no connection between them. The dredging would remove sufficient material from the mud flats and islands in the center of the bay to provide a new channel and create an oval course around the western bay.

Although there was considerable opposition to the causeway project, particularly over the decision to fund it using Mattoon Act bonds, it was finally approved in 1928, although continued litigation delayed the start of actual construction until mid-1929. The culvert and road construction on the south end of the causeway were finished in September 1929 and by January 1930 the 2100-foot fill in the middle of the bay had been completed. Work on the bridges continued during the summer of 1930 and by July the Union reported that it was possible to motor over almost its entire length except for the unfinished south bridge. Further delays and a change of contractors postponed final completion and a formal opening and ribbon-cutting (by cadets from the San Diego Army and Navy Academy in Pacific Beach) until January 1931.

The water and tidelands of Mission Bay were owned by the state, and in August 1929 the state declared it to be a state park. In 1945 the state transferred the nearly 4000 acres of tidelands in and around Mission Bay to the city and the city initiated condemnation proceedings to acquire more than 1000 other parcels of land along the southern and eastern shores of the bay. The city announced plans to develop Mission Bay as an aquatic park.

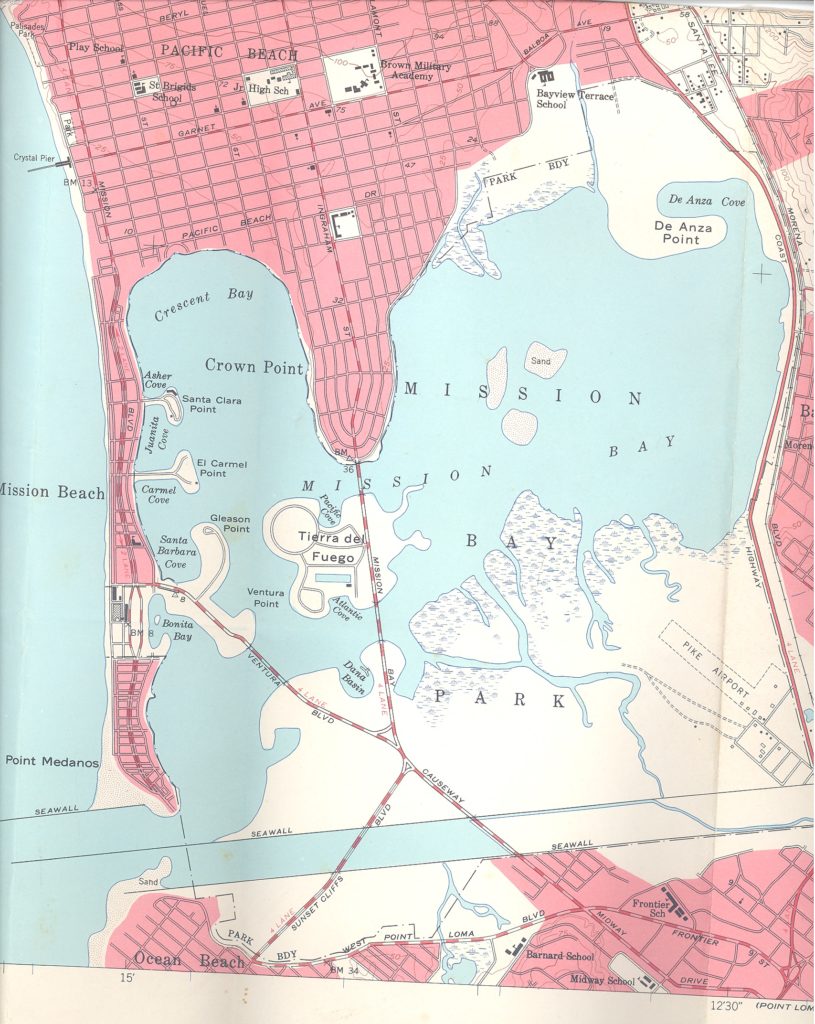

Although several dredging projects had been proposed to improve the park, none reached the implementation stage until 1942 when a contract was let to the Newport Dredging Co. for dredging and filling in the vicinity of Bonita Bay. However, wartime needs for the dredge at other places once again delayed the start of the project. When the company’s dredge, Little Aggie, did become available it was brought to Mission Bay and in January 1946 begin pumping 300,000 cubic yards of mud from the bottom of the bay to form a new peninsula extending northeasterly from the north end of Bonita Bay, the peninsula now known as Bahia Point. In April 1946 Little Aggie began work on a second contract, pumping 500,000 yards of mud from the bay and depositing the material in a southeasterly direction from the end of Ventura Place. This fill, now Ventura Point, was needed to form an approach for a new bay bridge, ultimately connecting Mission Beach to Ocean Beach and replacing the original bridge over the mouth of Mission Bay.

The original bridge became an issue for the next phase of Mission Bay park improvement, which called for the removal of 850,000 cubic yards of material to be used to build two points of land off the eastern shore of Mission Beach. The problem was that the dredge proposed by the Franks Dredging Co., the low bidder, was too large to fit under the bridge. However, city officials discovered that the Bayshore Railroad had been required to include a 40-foot section in the middle of the bridge that could be removed if necessary, and the Franks company agreed to stand the cost and assume any liability for opening the bridge for its dredge. The plan was to slide a barge under the removable section at low tide and let the rising tide lift the span free. Once the dredge had passed through, the barge would move the section back into position at high tide and have it drop into place with the falling tide.

This plan was put into action in October 1946, and the dredge, named Dallas, began work along the shores of Mission Beach. By December it had created Santa Clara Point and, by April 1947, El Carmel Point off Mission Beach and Tierra del Fuego Island, on the west side of the 2100-foot causeway fill. Meanwhile, the Newport company and Little Aggie had gone back to work dredging Dana Basin and building up Sunset Point on the eastern approach to the proposed new Mission Bay bridge.

The old Mission Bay bridge was opened again in November 1947 to allow dredges to pass under it. This time it was Little Aggie leaving the bay and the dredge Newport entering. The Newport was owned by the Newport company but had been leased to the Franks company to help the Dallas with a new contract to dredge a channel from the causeway to the northeast corner of the bay where it would also create De Anza Cove and De Anza Point. It actually took two tries to move the dredges through the bridge on this occasion; the removable section of bridge was removed but the water was too rough to attempt to tow the dredges through on the first try and the bridge section was replaced. The dredges were able to pass through the bridge on a second try a week later.

In 1948 the Newport and Dallas were put to work dredging the northwest portion of Mission Bay to a depth of 8 feet. Although some of the spoil was deposited on the northwest shore of the bay off the end of San Rafael Place, most of it was pumped across to the ocean side of Mission Beach and dumped in front of the Old Mission Beach lifeguard station in July, the height of the beach season. This aroused citizens of the area, who claimed it made the beach unusable and muddied the surf for almost a mile on either side of Old Mission Beach, forcing bathers to other areas where there were riptides and no lifeguards. The city apologized for the timing and offered to move the lifeguard station but refused to delay the work, adding that the material would actually improve the beach, filling up holes and widening the beach for miles up and down the shore line as the currents distributed the sand from the bay.

In September 1949 the Mission Bay bridge was opened up to allow the Dallas to move to San Diego Bay, where it dredged a deep water tuna clipper mooring between the foot of Ash Street and the Coast Guard Air Station. The bridge was opened again in March 1950 to allow the Dallas back into Mission Bay to participate in another dredging project around the bay entrance. This project included dredging a ‘pilot channel’ for a new entrance to Mission Bay between the north and middle jetties, which were then being built into the ocean from Mission Beach. The dredged material would be used to construct levees for a flood control channel extending east from between the middle and south jetties.

The new bay entrance would cut off the southern tip of Mission Beach, eliminating 700 feet of Mission Boulevard and the connection to the existing bridge, which was closed permanently in April 1950. In May 1950, while an excited crowd looked on, dredge operators cut a ‘navigable channel’ 150 feet wide and 8 feet deep between Mission Bay and the Pacific Ocean. An official dedication, including a boat race from San Diego Bay Bay to Mission Bay, was held on June 4, 1950. However, the expected widening and deepening of the channel was delayed because of the Korean War and sand bars and treacherous currents in the narrow channel caused a number of boating mishaps and drownings. After a particularly tragic incident in December 1951 took six lives, the channel was ordered closed until it could be dredged properly.

Another round of dredging in the De Anza Point section of the bay began in November 1951 and by August 1952 200 acres north of the bay, up to what would become the eastern extension of Grand Avenue in Pacific Beach, had been filled. The Mission Bay golf course and sports fields and Mission Bay High School were built on this land.

In August 1954 President Eisenhower signed a supplemental appropriations bill that included funds to complete the dredging of the Mission Bay entrance channel to a depth of 20 feet and a width of 250 feet. A contract was awarded in December and work began early in 1955. The Mission Bay channel was officially opened (again) in July 1955 during a festival which included a parade of boats, led by the mayor, and with the Buccaneer Band from Mission Bay High School playing in one of the lead boats.

In 1958 the City Council adopted a master plan for Mission Bay Park which specified that the entire bay was to be dredged to a depth of at least 8 feet and the spoil, some 17 million cubic yards, was to be deposited on an island in the east bay which was to be called Cabrillo Island. The contract was awarded in August 1958 to the Western Contracting Corp. of Sioux City, Iowa, which began the project by building a 180-foot-long dredge in Kansas City, Missouri, and towing it to Mission Bay via the Missouri and Mississippi rivers, the Gulf of Mexico and the Panama Canal, a trip of 4,400 miles. The dredge, named Western Eagle, arrived in April 1959 and began work in the northwest bay. By November 1959 Cabrillo Island was taking shape as the Western Eagle dumped sand from the west bay to build dikes around the perimeter of the island. The dredging moved to the east bay in early 1960 and was completed in 1961, although by the time the fill had settled enough to be usable Cabrillo Island was no longer on the map. In 1962 it was renamed Fiesta Island and Tierra del Fuego, the island that had begun as the 2100-foot fill for the Mission Bay causeway in 1929, became Vacation Isle. When the Western Eagle finally departed in August 1962, the transformation of False Bay, the sportsman’s paradise, to Mission Bay, the aquatic park, was substantially complete.