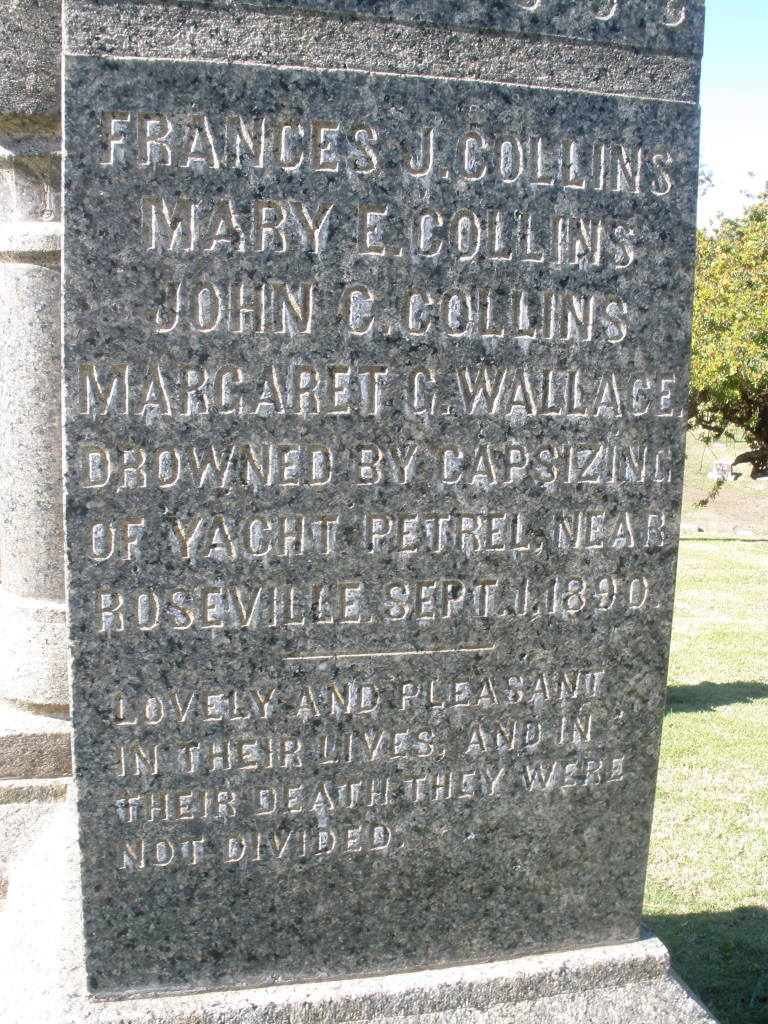

Mount Hope Cemetery in San Diego contains the graves of many early residents of the city, some marked by notable monuments. One monument is particularly notable for its intimations of tragedy; a young mother, her two children and another young lady share the same death date. Carved in a side panel is an explanation; Frances J., Mary E., and John C. Collins, and Margaret G. Wallace ‘drowned by capsizing of yacht Petrel, near Roseville, Sept. 1, 1890’. The name of the husband and father, John W. Collins, with a death date a year and a half later, is also carved in the monument.

The Collins family had come to San Diego from Wyoming in 1887 where J. W. Collins and D. D. Dare had been in the banking business. In January 1888 they opened the California National Bank with prominent local citizen William Collier as president, Dare as vice-president and Collins as cashier. In early 1890 a subsidiary, the California Savings Bank, was also opened, with J. W. Collins as president. The Collins family lived, appropriately, on Bankers Hill, in the magnificent Victorian home at the corner of First and Kalmia streets now known as the Long – Waterman Residence. J. W. Collins had purchased the house from John Long in June 1890 and sold it to Jane Waterman in November (Jane Waterman’s husband, Robert Waterman, was then governor of California and owner of the most profitable gold mine in San Diego County; his term as governor expired two months later and three months after that he himself expired at his new home and was also buried in Mount Hope Cemetery).

The Petrel was built in Boston and had reportedly won five races there before being brought to San Diego on the bark Wildwood in July 1888. That fall she competed in a series of races on San Diego Bay which apparently captivated the public, receiving front-page coverage in the San Diego Union. The Petrel, a sloop, and the Volunteer, a catboat, winners of their respective classes in a San Diego Yacht Club race, then raced each other in what the Union called one of the most exciting races ever sailed on the bay. The Volunteer won, but the winning margin of 14 seconds over a fifteen mile course was considered so trifling that the honors were said to be even.

The Petrel then faced off against the catboat Teaser in what was to be a series of three races. The Petrel was a sloop, ‘built for speed’, and could carry, in addition to a mainsail and jib, a club gaff topsail and jib topsail and a spinnaker for running before the wind. To balance all this canvas the Petrel also carried five tons of lead ballast. She was 25 feet long overall with a beam of 9 feet. A catboat like the Teaser had only a single mainsail and a wider beam. To compensate for these differences in class the Teaser was granted a time allowance 5 ½ minutes for the first race; conditions for the second race would be based on the results of the first. There would be no other restrictions on sail or ballast.

In their first race the Petrel crossed the finish line nearly 7 minutes ahead of the Teaser, winning even after taking the 5 ½ minute allowance into account. In the second race, held a month later, the Petrel won easily but it was not considered a fair race owing in part to light winds. The third race was apparently never held; in August 1889 the Union complained ‘What is the matter with a race between the Teaser and the Petrel? These crack little yachts should make a gallant race and all San Diego would turn out and watch the struggle for supremacy’.

By 1890 the racing frenzy had apparently cooled, or at least was no longer front page news in the San Diego Union, but the Petrel remained at Hunt’s boatyard on the bay where her owner, John Young, took her out sailing most Saturdays. On the last Sunday in August Captain William P. Hay, a local shipping agent, approached Mrs. Collins at the United Presbyterian Church and remarked that he intended to take Mrs. Hay for a sail on the bay Monday if he could get a suitable yacht. He asked Mrs. Collins if she would like to join them and when she replied that she would Capt. Hay told her to meet him at Hunt’s boatyard at 10 o’clock in the morning and to bring her children Mary and Johnny and a picnic lunch. Capt. Hay also invited Miss Maggie Wallace, the pastor’s daughter, and she also accepted. Mr. Collins was away at the time, on a business trip to San Francisco.

At about 8 o’clock Monday morning, September 1, 1890, Capt. Hay telephoned Mrs. Collins to tell her that he had secured the Petrel, ‘a yacht well known in San Diego waters’, and that everything was in readiness for a delightful sail on the bay. Mr. Hunt brought the Petrel in from her mooring and the party sailed away about 10 o’clock. Conditions on the bay were not ideal; according to the Union there was a pretty stiff breeze blowing and ‘white caps flashed like puffs of steam from a million factories’. Hunt was concerned enough to suggest to Capt. Hay that he take in some of the sail but Capt. Hay replied ‘Oh, I guess not. I’m a pretty good hand at sailing anyway. I guess she’ll go all right’.

About noon a group of Portuguese fishermen at Roseville, on the west side of the bay near Ballast Point, saw a yacht sailing down the channel. Suddenly they saw that ‘a gale had struck the cloud of canvas’ and the yacht suddenly careened, tipped her nose and went straight down. The fishermen jumped into boats and pulled out to where the yacht had gone down but found no trace of the yacht or her occupants so they returned. A German fisherman returning to the bay later reported that he was startled to see a woman’s body floating in the water and he began to retrieve it when another body came to the surface nearby. This shocked him enough that he released the woman’s body and departed, ‘abandoning the drowned persons to the mercy of the sharks and fishes’ and ‘incurring much public censure’. Rumors of a disaster reached San Diego about 3 o’clock and search parties converged on the scene but found nothing that evening except for a coat which was identified as belonging to Capt. Hay and a fruit jar and other items which may have been part of a picnic lunch. The Union reported the following morning that all that was certain was that the party of six had drowned and no bodies had been recovered.

In the immediate aftermath and in the absence of any real evidence of what had occurred, the Union reported the speculation of other members of the waterfront community (all of whom were also apparently called ‘Captain’). A Captain Kehoe said he had seen the party depart from Hunt’s boatyard and that he would not have gone out in that yacht with such a sail in so strong a gale. She was not safe under so much canvas and only the most experienced sailor should have attempted it. ‘A boat built as she was will tip very easily, and she had so much lead in her that once full of water she was bound to go down like a stone’. The Petrel’s owner, Captain Young, said that he had only agreed to allow Capt. Hay to use the boat because he understood that another experienced Captain would also be aboard, and that it would not be safe for one man to take out a party of women and children.

The next day searchers hired the tugboat Santa Fe and returned to the site of the sinking. A weighted line was dragged along the bottom and soon snagged an obstacle which was raised far enough to identify as the sunken yacht. When it had emerged far enough for its mast to be lashed to the tug it was brought back to the docks where a crane would be used to raise it out of the water the following morning. Meanwhile, the body of Mrs. Collins had been found floating in the channel. A message was dispatched to friends of Mr. Collins in San Francisco conveying as many particulars of the calamity as necessary and requesting them to break the intelligence to Mr. Collins so that he might receive it as gently as possible. Apparently this was done and word was received that he would be in San Diego on Wednesday evening.

The Union also began a campaign to place some of the blame on what it perceived to be the inadequate efforts of the first responders, who were conspicuously identified as foreigners. The Portuguese, who had actually witnessed the accident and responded immediately but found no survivors or wreckage, were now said to have made no effort whatever to rescue the drowning and drowned, nor to locate the sunken yacht. ‘They are a churlish and unsentimental lot, to be sure, but even the most superlative boorishness is not accepted by the people as sufficient reason why they should have manifested such supreme and inhuman indifference to the fate of the party’. The German fisherman who had attempted to recover the body of a women but then released her upon the appearance of another corpse was ‘not a popular individual at present’. The Union inferred from his description that it was probably Mrs. Collins that he had begun to recover and that the second body was one of her children, based on the fact that ‘he intimates as clearly as his incomprehensible stupidity will permit that it was the body of a child’. ‘Who knows? Perhaps there might still have been a spark of life in that mother or her child; perhaps they had not been long in the water; perhaps had they been towed at once to shore resuscitation would not have been impossible’.

At the dock the Petrel was raised and although it had been expected that one or more of the bodies would be found on board the only vestiges of the picnic party were three parasols, those of the women on board, a small jar of jelly and a few other articles. The yacht itself had received comparatively little damage and could soon be repaired, although the Union speculated that her owners would probably ‘not be compelled to refuse many requests for her service hereafter’. Also, an accident like this would revive her past record; ‘before she came to this coast she carried a party of four to the bottom of the Atlantic ocean and at another time a party of eight and that in a race in Pacific waters a year or more ago she dipped enough to create consternation among her occupants and compel them to bail her out with hats’. The search for the other bodies continued; the bay in the vicinity of the sinking was dragged, and cannon were fired over the water and dynamite dropped into the bay in the belief that this would raise drowned bodies.

Although it was at first intended for Mrs. Collins’ funeral to be held at her late home, at the corner of First and Kalmia, it was deemed more appropriate to hold it at the Presbyterian Church, where friends and relatives gathered to pay their respects to the only recovered victim of ‘the most horrifying calamity that ever happened in the bay of San Diego’. After the service Mr. Collins and Rev. Wallace entered a closed carriage and the cortege moved away to Mount Hope Cemetery.

The bodies of the other victims turned up over the next few weeks. Mrs. Hay’s body was found floating in the surf about three miles south of the Hotel del Coronado on September 5. Her beautifully engraved gold watch had stopped at 11:39, presumably the very instant the capsizing had occurred. Also found nearby were two straw hats, one black, evidently the headgear of an elderly woman, and one white with a black-headed shawl pin thrust through it ‘in the fashion that ladies usually pin their hats to their hair’. The one was thought to have belonged to Mrs. Hay and the other to Miss Wallace. These findings were cited as evidence that the bodies would probably be found south of the bay, but on September 9 searchers dragging the channel found the body of William Hay almost on the spot where the yacht had disappeared.

On September 17 fishermen recovered a body of a child about two miles south of the head of Point Loma and returned it to San Diego. This turned out to be the body of Mary Collins, which was soon conveyed to Mount Hope. Miss Wallace’s body was found by a fisherman inside the bay on September 25 and a graveside funeral was held at Mount Hope. Finally, on October 6, the body of 9-year-old Johnnie Collins was found off Ensenada and after the necessary permits had been obtained from the Mexican consul and the Collector of Customs the body was returned and also interred at Mount Hope.

A few weeks later the news was that Dr. Bowditch Morton had bought the ‘famous yacht Petrel’ and proposed to have her put in first class order. He claimed to not have the least fear in using her when she is in proper repair. He would cut down her sails, put in airtight compartments and reduce the ballast.

Three years later, on October 26, 1893, a Captain Maitland of the British ship Valkyrie took two friends for a little cruise in the Petrel. In the stream, abreast the Santa Fe wharf, in a choppy sea caused by an ebbing tide and west wind, a sudden squall struck the sail and almost capsized the sloop. Capt. Maitland slacked the line and righted her but the boom swung around and struck the water and ‘in a twinkling the treacherous old craft was lying on her side, with Capt. Maitland and his friends in the bay’. The Union noted that there had been doubts expressed about Capt. Hay’s seamanship in the Collins tragedy but since Capt. Maitland’s seamanship could certainly not be called into question this accident demonstrated that the craft herself was unseaworthy and luckless. ‘The Petrel is regarded as a hoodoo along the waterfront. She has been remodeled and trimmed since the Collins tragedy, but she is built upon the wrong plan and won’t stand up if she has half a chance to lie down’.

John W. Collins had been out of town on September 1, 1890, and had not been directly involved in the Petrel disaster, but he was soon to be involved in a tragedy of his own making. In January 1891 he had become president of the California National Bank (and relinquished the presidency of the California Savings Bank). On November 12, 1891, customers were surprised to find the bank closed, with a note on the door explaining that ‘owing to continued shrinkage in deposits and our inability to promptly realize on our notes and accounts, the bank is temporarily closed’. The next day the subsidiary California Savings Bank also closed. A day later a national bank examiner assumed charge of the California National Bank and announced that the results of his examination would be forwarded to the comptroller of the currency and any further information would have to come from Washington. A few weeks later, based on his report, the comptroller of the currency appointed a receiver to oversee operations of the bank with a view to resumption of business within three months.

The resumption of business never occurred. On February 25, 1892, J. W. Collins was arrested at his rooms at the Brewster Hotel on a charge of embezzling and appropriating to his own use $200,000 of the funds of the bank. Bail was set at $50,000 and ‘in order to not create any excitement by Mr. Collins appearing on the street in charge of an officer’, he was confined to his rooms at the Brewster in custody of an officer while his friends attempted to secure the bond. On March 3, when the bond had still not been raised, a United States Marshal was sent to bring him to Los Angeles until his preliminary hearing. While the authorities waited outside Collins went into his bedroom as though to pack his valise. A shot rang out, officers burst into his bedroom, which was empty, then into the bathroom, where they found him stretched on the floor alongside the bathtub, blood pouring from his mouth and a smoking revolver in his hand. A doctor was summoned and pronounced him dead.

The Union accompanied the front-page news of Collins’ suicide with an editorial recalling the Petrel disaster; ‘The crash of the bullet that closed the chapter of the life of J. W. Collins yesterday afternoon was the last act in the tragedy that wiped the unhappy man’s wife and children out of existence two years ago on the bay. Even the most implacable enemy of Mr. Collins must admit that, embezzler of other people’s money though he may have been, the memory of his drowned babes and his wifeless home must have been strong upon him in that desperate extremity when he determined to escape further misery by the avenue of the suicide. The capsizing of the Petrel, the failure of the bank, the suicide of Mr. Collins – they make up the most tragic story ever chronicled in the history of San Diego county’.

On March 5 the body of John W. Collins was buried alongside his wife and children at Mount Hope. On April 4 the report of the receiver of the California Savings Bank revealed that it had been a front, operated as a ‘mere receiving depository’ of the California National Bank. Cash had been transferred from the California National Bank or simply entered in the books when necessary to make a good showing on reports. The July 1892 report of the receiver for the California National Bank was even more shocking, revealing that Mr. Collins had embezzled nearly $800,000 from the bank. ‘Although there have been published from time to time the most sensational statements regarding his methods of doing business and conducting the affairs of the bank, nothing has caused such undisguised astonishment as the facts brought to light yesterday’, the Union reported. ‘Just what methods Mr. Collins employed to bring about such a condition of affairs it is impossible to even conjecture. It will be apparent, however, to everybody in the least conversant with banking rules or business customs that they must have been decidedly irregular, if not actually criminal’. D. D. Dare had also looted about $400,000, making the total amount chargeable to them nearly $1,200,000, a staggering sum in the 1890s (Collins’ mansion at First and Kalmia had cost him $17,000). The Union concluded that ‘What has become of this vast sum of money is not known and probably never will be. Mr. Collins is dead and Mr. Dare is enjoying a secluded life in some obscure spot in Italy. Neither are in a position to explain, and probably would not if they could’.

The affairs of the defunct bank were unwound in dozens of legal actions over the next decade. A final auction of the bank’s assets was held in 1899; notes and other securities with a face value of over a million dollars were sold for $3350. San Diegans were occasionally reminded of the California National Bank fiasco when news of D. D. Dare filtered back from Europe; in 1894 he was said to be a portrait painter in Athens, Greece; in 1914 he applied to have his indictments withdrawn so that he could return to his beloved California, but his request was denied; in 1922 he was reported to be in Constantinople, Turkey, supporting himself selling prayer rugs. His indictments finally were dismissed in 1926, but by then he was thought to have died in Greece.

According to the San Diego Union, these reports called to mind a remarkable theory which was current in San Diego at that excited time and which received some credence; that President Collins, who was supposed to have killed himself after his arrest at the Brewster Hotel had actually escaped and joined Dare in Europe. A plaster cast was said to have been given to an undertaker who was ‘in on the deal’ and that this was buried as Collins’ body. Whatever lies in his grave, John W. Collins’ memory is preserved along with the Petrel victims on their monument at Mount Hope.