In November 1897 the ‘personal mention’ column of the San Diego Union mentioned that Misses M. J. and L. Clarkson of Melrose, Massachusetts had arrived in the city to remain for the winter. They must have liked it; barely a month later the paper reported that ‘The New Thought’, a monthly publication of sixteen pages whose home is at Melrose, Mass, had announced that their editor and publisher, M. J. Clarkson, and associate editor, Lida Clarkson, had crossed the continent to make their new home at San Diego.

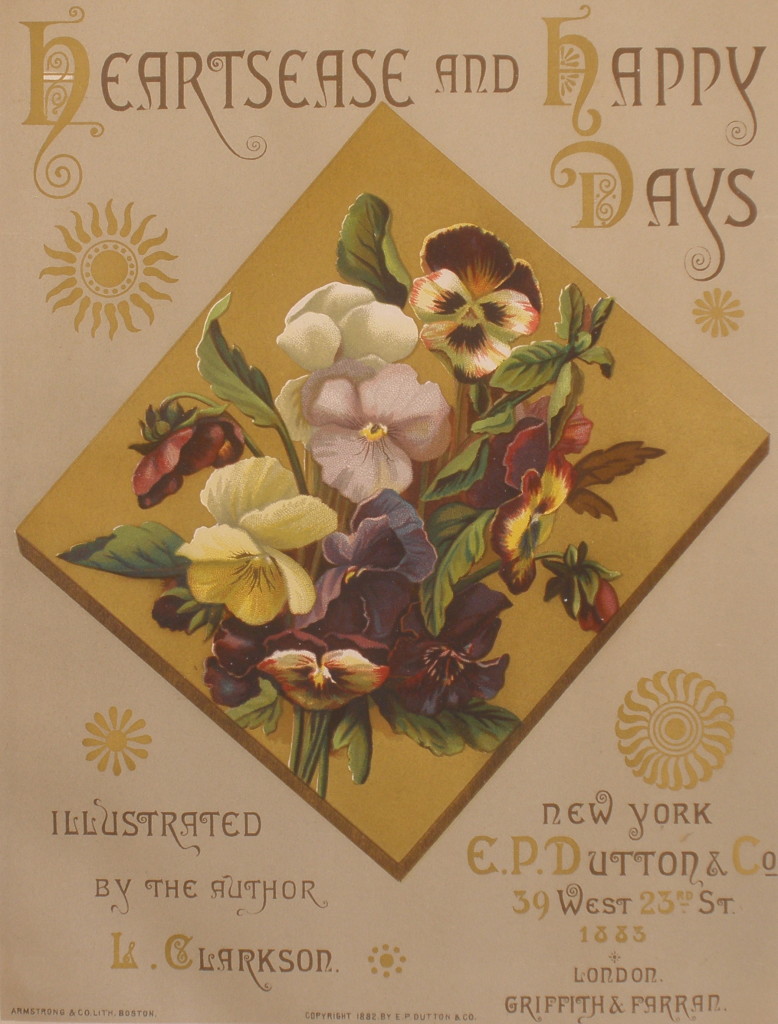

Actually, while The New Thought was the sisters’ most recent venture, both had already experienced remarkable careers in publishing. When Mary Josephine Clarkson married Carl Akerman in San Diego a year later the Union noted that the bride had been connected with her sister in editing a department of the Ladies’ Home Journal for three years and afterward edited an art magazine for eight more years before becoming interested in metaphysical study and launching her journal. Lida Clarkson was an accomplished artist and author of books on home decoration and art instruction, based on articles she had contributed to Ladies’ Home Journal. She also produced a number of color plate gift books featuring chromolithographs of botanical themes and poetry.

In February 1900 Lida Clarkson purchased Thomas Fitzgerald’s home at the northwest corner of Bayard Street and Reed Avenue in Pacific Beach for $300. This home, on lots 22 and 23 of Block 262, was the eastern-most of the row of houses that had been built by railroad employees working out of the depot grounds at the end of the railway line. The paper reported that she was having the house remodeled. A week later she also bought the lots across the alley, lots 20 and 21, the southwest corner of Bayard and Thomas, consolidating her ownership of the east end of Block 262.

In July 1900 Lida Clarkson paid $700 for an entire block, Block 264, between Cass and Dawes Streets and Thomas and Reed Avenues, where the Pacific Beach branch library now stands, and only a block from her other properties. In November she sold this block to the Akermans and they moved in with Miss Clarkson while superintending the improvements on their property.

John Maynard Rockwood was a miner who operated in the San Diego County backcountry, particularly in the Mesa Grande mining district. He bought and sold mining claims and in 1899 made news for selling a Mesa Grande mine for $4000. While not in the mountains he lodged in the home of Elbert Higbee, one of the very first houses in Pacific Beach, located near the foot of Bayard Street just a few feet from Mission Bay. Mr. Higbee was a painter and Mr. Rockwood was reported to have joined him in painting the Pacific Beach schoolhouse in 1896.

When Miss Clarkson moved to the southwest corner of Pacific Beach in 1900 she and Mr. Rockwood became neighbors and shortly afterward, in July, the Evening Tribune reported that a marriage license had been issued for John M. Rockwood, aged 48, and Lida Clarkson, aged 45. A few days later the Tribune reported that Miss Clarkson and Mr. Rockwood had married and would make their home ‘on the Beach’. The paper added that Mrs. Rockwood was one of the most celebrated women in the country as Lida Clarkson, known far and wide as art editor of The Ladies’ Home Journal and with a world reputation as an artist.

The couple’s ‘home on the Beach’ was Mrs. Rockwood’s house at Bayard and Reed, and in 1901 they added a second story which the Tribune claimed would make it one of the finest residences on the Beach. Over the next few years the Rockwoods bought up most of the rest of the block, eventually owning all but 4 of the 32 lots in Block 262, surrounded by Bayard, Reed, Thomas and what was then the railroad spur to the depot grounds and later Mission Boulevard. Some of these lots were won in public auctions at the courthouse door, sold by the Tax Collector because the Pacific Beach Company had failed to pay the property tax of 11 cents in 1893 and the taxes had remained delinquent over the intervening years.

In August 1904 a San Diego Union article described the remarkable activity in building operations in Pacific Beach in the past week, the most noticeable being the commencement of a magnificent and spacious apartment house, the first structure of its kind in Pacific Beach, being constructed by John Rockwood on Bayard near Grand Avenue. It would contain sixteen apartments with all the modern conveniences and with bathroom accommodations. The Rockwood, as the apartment building was first called, was located on the west side of Bayard, just north of the alley separating it from the Rockwoods’ home at Bayard and Reed, and residents were moving in by 1905. Beginning in October 1907 the Union advertised The Rockwood, rooms and board, 3 blocks from beach bathing, no undertow. Teams to all points of interest. Braemar Sta., La Jolla R.R.

The dining facilities were apparently the highlight of the Rockwood’s design. A 1909 Union article mentioned that the Monday Night 500 club was royally entertained by the Braemar 500 club at the Rockwood flats on the Ocean Front. The large dining room was beautifully decorated for the occasion.

However, The Rockwood does not appear to have been much of a success commercially. The advertisements in the Union disappeared after a few months. By 1911 it had also disappeared from the city directory and J. M. Rockwood no longer described himself as proprietor.

In 1912 the apartments were reopened under new management and with a new business model; a Union article in July noted that M. A. Raines had opened the Rockwood Apartments at Pacific Beach and would make a specialty of entertaining week-end parties. Chicken dinner would be served on Sundays. Apartments for the week or month could be arranged for at reasonable rates. According to ads in the Union the Rockwood Apartments had housekeeping rooms with free gas for cooking, electric lights, telephone – all modern conveniences; ‘Take La Jolla car, get off at Ocean Front Station’. The dining room remained an important draw; another ‘elaborate luncheon’ was put on by the ‘charming hostess of the week’ Mrs. George Hannahs at the Rockwood Apartments at Pacific Beach.

J. M. Rockwood died in February 1915 and in 1916 Lida Rockwood sold her remaining holdings, which by then consisted of 10 lots at the east end of the block including the home at Bayard and Reed and the apartment building, to her nephew David Clarkson. In 1918 her brother-in-law Carl Akerman also died and shortly afterward she moved out of the Pacific Beach home, where she had continued to live, and joined her sister at the Akerman home on I (now Island) Street in the Grant Hill neighborhood of San Diego. Mrs. Rockwood died in 1924 and Mrs. Akerman in 1931; the home on Island Street is still standing.

Captain J. M. Ray and his wife Estella had been the officers in charge of the Salvation Army’s Maud B. Booth Children’s Home in San Diego. In 1916 J. M. Ray bought the St. Lawrence Hotel on H (Market) Street downtown. The St. Lawrence had previously been a Helping Hand Home, a refuge for the ‘deserving poor’, and many indigent people still came to the St. Lawrence hoping to find assistance. If Ray had room he would sometimes put them up and eventually, with assistance from the Board of Supervisors, he found himself furnishing about 40 rooms for the ‘aged and decrepit’. When the numbers continued to grow Ray got more help from the board to establish a home for aged women in Pacific Beach: the Rockwood Apartments. The home in Pacific Beach, managed by Estella Ray, eventually became known as the Rockwood Home for the Aged (the St. Lawrence Hotel downtown also became the Rockwood Hotel, before it was torn down in 1923). A U. S. Census enumerator recorded a matron and six patients, ranging in age from 73 to 88, at the Rockwood Home in January 1920.

In about 1919, after Lida Rockwood had left to live with her sister in Grant Hill, the Rays moved into her former house at the corner of Reed and Bayard, across the alley from the Rockwood Home. While living in Pacific Beach the Rays experienced a family tragedy when their 16-year-old son Dwight was accidently shot on December 31, 1919. According to the Evening Tribune, he and two companions were returning home when they decided to fire a volley to salute the new year. One of the companions’ gun hung fire and when he tried to unload it it fired, striking Dwight Ray in the back of the head and killing him. The paper noted that the younger Ray had attended the Army and Navy Academy and that his father was superintendent of the Rockwood Home for the Aged in Pacific Beach. Tragedy also struck the home itself in 1921 when an 80-year-old woman burned to death after a lighted oil stove overturned, setting her clothing afire and scattering burning oil over her room.

The Rockwood Home for the Aged operated for about five years in Pacific Beach. A 1920 Union article summarizing the home’s treasurer’s annual report gives an idea of the scale of their operation. Expenses were said to be $5670 while income was $5844, about half of which was supplied by the county. More than 7000 free meals were served, out of a total of 44,500 meals. 2500 beds were furnished free. The article explained that old people whom relatives and friends could not care for personally were sent to the home and board and rent was paid. Other aged were kept by the home without any payment (which was presumably made up for by the county).

By 1923 the home had outgrown the former apartment building in Pacific Beach and the Rays moved the residents to the Palms Hotel building at the northeast corner of I Street (Island Avenue) and 12th Street (Park Boulevard) downtown. The Palms Hotel was formerly the Bay View Hotel, built in 1889 on the site of an earlier Bay View Hotel which had been in existence since the 1870s. The new Rockwood Home at the Palms Hotel was much larger than the Pacific Beach facility, more than a quarter of a city block, and within walking distance of most points of interest downtown. The Evening Tribune reported that it had all the conveniences of a first-class modern hotel with over 100 large airy rooms, each one located so that guests would have easy access to the dining rooms, reading rooms and the sun porch. Mrs. Ray, the kindly little lady who was giving so freely of her time and money for a cause that was dear to her heart, told the Tribune correspondent that ‘We are trying to do good work here, and we are meeting with wonderful success’.

After the aged residents were moved downtown, J. M. Ray used the Rockwood apartment building as headquarters for his short-lived real estate company in 1924 and after that it apparently reverted to being an apartment or rooming house again. The city directory showed two residents at the 4270 Bayard Street address in 1925, one in 1926 and one 1927. In 1928 4270 Bayard was vacant, but one resident was listed in 1929. From 1930 to 1932 the city directory showed 4270 Bayard as vacant and after 1932 the address was no longer listed. Today a large apartment or condominium building with underground parking covers the northeast corner of the block but a row of Canary Island date palms, now nearly 100 years older and considerably taller, still line Bayard Street just like they did when the old folks posed for a photo in front of their home about 1919.

Postscript:

After buying the Palms Hotel and assuming a large mortgage the Rays apparently planned to increase occupancy by offering ‘life memberships’; room, board and care for life, for an advance payment of between $1000 and $3000. They did recruit a number of ‘life members’ but over time they found that their expenses exceeded the income generated by these payments and began engaging in dubious practices to try to make ends meet.

In 1927 ‘inmates’ of the Palms Hotel for the Aged (as they were called) began complaining of financial irregularities. In April a 70-year-old woman who had paid $1050 for a life membership filed suit against the Rays contending that they had not lived up to the terms of their agreement. In September she was awarded a judgment of $1390.

In October 1927 the Rays apparently just walked away from the home and abandoned the inmates. The Union reported that 63 inmates of the Palm Hotel for the Aged, including 48 ‘life members’ who had paid in advance for care for the remainder of their lives, enjoyed a good dinner through the intervention of the county board of supervisors after it appeared that the aged unfortunates would have to go to bed ‘supperless’ . Mr. and Mrs. J.M. Ray, owners of the hotel, had been absent for several days. A grand jury was investigating the situation.

In November Mrs. Ray answered a subpoena to testify to the grand jury and while she was at the courthouse waiting to be called she was arrested for violating state wage laws by allegedly paying employees with post-dated checks. Mrs. Ray was later convicted of this misdemeanor and fined $25 for each check. Mr. Ray was still ‘absent from the city’ but he was finally brought into court a week later on a bench warrant charging him with failing to obey a subpoena. Meanwhile, the county welfare board heard from inmates that the Rays had collected $13,260 so far this year for life memberships. Nine men and women said they had paid from $1000 to $3000 each for a home and care for the remainder of their lives but were left stranded when the Rays left the place.

Although the county board of supervisors had stepped up to provide supper, and were able to find room for a few of the inmates at the county poor farm, there was little to be done for most of them. The Rays were unable to make their payments on the mortgage, the hotel was sold at auction in March 1928, and the remaining inmates were turned out on the street. The grand jury returned indictments against the Rays for grand larceny, embezzlement and obtaining money under false pretenses, but in three separate trials over the next few months none of the charges stuck; some were dismissed, others resulted in mistrials, they were acquitted on some charges, and Mrs. Ray’s appeal of her two convictions was upheld by an appellate court.

In 1929 the state supreme court overturned Mrs. Ray’s appeal and, faced with yet another trial, she pleaded guilty to the embezzlement of funds from an elderly man for whose estate she had been appointed guardian. She appealed to the court for a sentence of probation only but her probation report recommended that she serve jail time. Although the papers didn’t report the outcome, the fifteenth census of the United States, enumerated in April 1930, included a page for the San Diego County Jail which listed a Ray, Estella, age 53, prisoner. And, on the same day that Mrs. Ray received word that the supreme court had denied her appeal, Mr. Ray, the former Salvation Army officer, was arrested for drunken driving. Ray’s car had become ‘tangled’ with two others, one of which was driven by Policeman Mike Shea. Officer Shea said Ray appeared to be in a ‘stupor’.

The Palms Hotel is still standing at the northeast corner of Park Boulevard and Island, a magnificent example of a late nineteenth century hotel building.