‘This is

all news to me.’

Dan Webster (2008)

Dan Webster (2008)

In 1959 Dr. John C. Webster, a research psychologist with the Naval Electronics Lab in San Diego, was awarded a National Science Foundation fellowship for a year of study at the prestigious Applied Psychology Unit in Cambridge, England. The year was also to include professional meetings in Montreal, Stuttgart, Essen, Paris, and Bonn, trips to meet and work with European scientists in their labs as far afield as Stockholm, and a cruise on a Royal Navy ship in the Mediterranean. But what made this year particularly momentous for some of us was that Dr. Webster, Dad, took us along (except for the Mediterranean cruise); Mom (Mary) and the five brothers, John (11), Tom (7), Bill (5), Charlie (3) and Dan (who celebrated his first birthday the day we took off). And, in addition to the professional papers and reports from his scientific studies, Dad took the time to record this extraordinary family adventure in a manuscript which he titled Daniel Webster’s Year Abroad[1].

Daniel Webster’s Year Abroad is primarily a travelogue, documenting our journey across the United States and the Atlantic, sightseeing trips to London and other British destinations, lengthy vacations on the Continent in a VW camper (planned around professional meetings or lab visits), and finally the long cruise home through the Panama Canal. Each chapter describes new scenes and adventures, but also challenges; language, logistics, driving conditions (Dad’s obsession) and of course the problems posed by five small boys.

This was the world of a half-century ago, with ocean liners, steam locomotives, horse-drawn carts and a Europe still recovering from the physical and economic damage of World War II. This was long before cell phones, credit cards or ATMs, not to mention the internet and email. Once you left home you were pretty much out of contact, although some trips included a stop at a designated post office for mail forwarded ‘poste restante’. Expenses were paid in cash or travelers checks. And we weren’t the only family attempting to see Europe under these conditions. As night fell and travelers congregated in the camping sites it wasn’t unusual to find another VW camper full of Americans, sometimes heading for the same meeting.

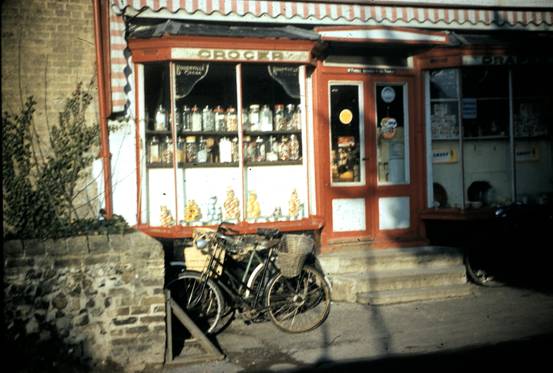

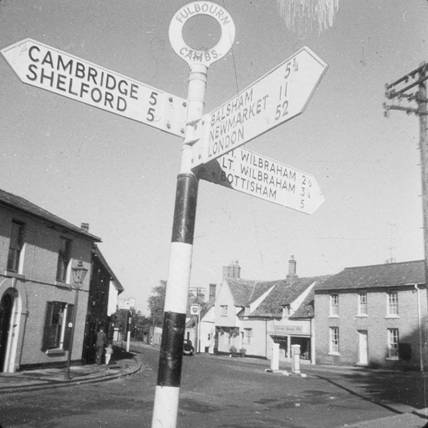

Of course we didn’t spend the whole year on the move. The other theme of Dad’s book was home life in an ageless English village. In many ways this was a step back in time. There was a medieval church around the corner. The streetlights were gas. We lived in a nineteenth-century former Manse heated by coal fireplaces in each room. Kitchen appliances were primitive (although there was a tiny refrigerator). There was no telephone. Dad found a wealth of material in the differences he observed in British culture, schooling, politics, food preferences, and, inevitably, driving habits.

You might think that the challenges of living and working (or attending school or minding toddlers) in a foreign country and occasional weeks-long camping trips would be entertainment enough, but Dad couldn’t resist the cultural opportunities in nearby London; operas, ballets, plays, the Royal Tournament, etc., and he took as many family members along as possible. He also found time to play clarinet with the Cambridge University Musical Society orchestra for a week’s performance of the “Damnation of Faust”. And of course there was participation in ‘chapel’ and school activities.

At the end of the year we left our English village to return

home. Remarkably, Dad was able to

arrange a sequel, in 1966, which duplicated Daniel Webster’s original year

abroad in almost every detail; Dad worked at the same Unit, we lived in the

same Manse in the same village and made camping trips to the continent in the

same type of VW camper (a 1967 model, not a 1959 model). There were

differences, though. The postwar recovery had continued to sweep across Europe.

Dad had access to the PXs in the many nearby US Air Force bases for those

previously unobtainable American staples. The Manse not only had a telephone

but a TV, and horror of horrors, there was even a channel with commercials. The roads were not much better but were even

more crowded, with the new Minis. The

BBC had made way for the Beatles and pirate radio. And the boys, now 8 – 18,

were probably not as entertaining either. Somehow Dad never did get around to

writing Daniel Webster’s Year Abroad, the Sequel.

“Is this England,

Daddy?” asked Charlie, our three-year old as the airplane landed.

John, our oldest

boy, who had been literally shaking with fright all the way from San Diego said,

“No, Charlie, this is Phoenix.”

Then Charlie asked Tom, our seven-year old, “Did you see the toy cows down there just before we landed?”

And agreeable Tom

said he had. So started our trip to

spend a year studying in Cambridge.

Actually of course it

started much earlier, when I applied for my fellowship. Not much was said to the five boys then

because of the odds on chances the fellowship wouldn’t be granted.

I suppose we can

say the trip started six months earlier, 4 December ‘58. On this day, one day before I expected to be

on pins and needles awaiting the

outcome of my application, the phone rang at work during my noon hour. The phone always seems to ring during our

relaxation period after lunch, and right in the middle of our dart game. In fact we had gotten in the habit of taking

it off the hook, since nobody took seriously

my solution for telephones, namely that all telephones the world over be

connected to make outgoing calls only.

Anyway the phone

rang and after letting it ring long enough to find out it was an “outside”

call, I finally answered it. You see

calls from inside the laboratory had regular rings since they worked off the

automatic switchboard while outside calls were handled by an operator who rang

longer and seemingly louder, the longer you tarried in picking up the phone.

Back to the

call. It was Mary, my wife, who seemed

to know exactly when our dart game was in progress. Although she phoned only about once every

second week she always caught us at darts.

So I wondered which boy had just broken our kitchen window again. But no, she said I had a letter from

Washington. This was really not too surprising, my mother lived

there, I work as a scientist for the navy and they have some sort of office in

Washington. I couldn’t yet see what occasioned the phone call, and anyway it

was my turn to throw the darts. Then she said it was from the National Science

Foundation. That stopped the dart game,

but as a disinterested spectator I asked if she had opened the letter and she

allowed as she had. From the obvious

lack of enthusiasm I figured I needn’t ask her any more questions. But with

obvious relish she stated was just a form letter. I had expected a form letter

telling me the sad news but thought it would come to me at the laboratory the

following day. I figured successful

candidates would receive long distance phone calls and duffers like me form

letters.

So with dejected

resignation I asked the final unnecessary question, what did it say? Never

raising her voice once she read “you have been selected as a Senior Post

Doctoral Fellow and will begin your tenure on or about 1 July at Cambridge

University.”

Even Mary couldn’t

pull that serious a hoax on me so I just about believed what she read must be

so. After a stunned period of dead silence I finally quizzed her again and she

continued “details follow.”

On returning home

that afternoon John 10, Tom 6, Bill 5, Charles 2, and Dan, that is Daniel

Webster age 6 months, were beaming from ear to ear. Charles wanted to know if

he could take his tricycle to England, which he figured must be as far as Uncle

Harold’s, 10 miles away.

Then came the hard

work. Johnny wouldn’t fly across the ocean no matter what, and all tourist

space on ships in June was already taken; solution we go by ship in May.

Our up-to-date

cars, ‘40 Dodge and ‘49 Pontiac Station Wagon wouldn’t get us, not with my

nerves, all the way across the United States; solution fly to Iowa, visit

relatives and filter on to east coast.

If flying, our present

luggage was too heavy; solution buy new light-weight luggage.

To see Europe with

5 small boys on scientist’s earnings cheap transportation and lodging would be

needed; solution order a Volkswagen Microbus complete with camping equipment.

This required correspondence to Germany where the camping equipment installers

decided we should have their longest luggage rack for “with these many boys you

will have much luggage”.

Getting rid of our

cars and arranging to rent the house were just part of the logistics problems

encountered.

The boys’ rolling

stock, 4 bicycles, 4 tricycles, wagons, scooters, 4 baby buggy wheels, etc.,

also had to be loaned out.

We decided to have

mom and four smallest boys on one passport.

The photographer earned her money that day. A witness was needed on our passport

application (and our friends have children too) so seven of us plus another

mother and two children started off to the court house. It so happened

passports and marriage licenses were issued in adjacent offices and the

passport lady was gone when we arrived.

The marriage license lady was handling passports. It didn’t occur to us that this created quite

a sight to the sailors and their girls who came after we had been ushered into

the marriage license office. I saw a few whispered conversations and felt

awfully sinful somehow but we did get our passports.

Actually we gave

the oldest car to Harrell and Dion Hurt, some church friends (at least they

were our friends) with instructions “If it lasts till we get back we want it

back, if it doesn’t it has long since paid for itself.” As a matter of fact, like Old Ironsides or

the One Hoss Shay that car never gave a moment’s trouble and on many occasions

we used it to get our new (1949) car and many other new cars started.

The station wagon

we gave to the church as our pledge for the rest of the year and besides “with

these many boys” I hadn’t the time to try to pawn it off on any one anyway.

Finally:

T’WAS THE EVE OF DEPARTURE

T’was the eve of departure

And all through the night

Was poor mama at packing

With morning in sight

The children were tossing

Too warm in their beds

While dread visions of’ flying

Thrashed through their heads.

At first there was flying

And relations to see

Then miles of driving

And a ship cross the sea.

Since the flying was first

And the bags need be light

With five children to pack for

Did mom have a fight.

To get clothing and playthings

For one year abroad

She was sorting and stowing

And would not be awed.

When out on the porch

There arose such a clatter

That we stopped all our work

To see what was the matter.

There were neighbors and church friends

With candy galore

And we sat and we chatted

Till back to the chore.

From seven to thirteen

The bags did increase

And then to our sorrow

We just had to cease.

Then laying our fingers

Aside us in bed

And getting two nods

Up for traveling we sped.

We looked like some peddlers

Just closing our packs

When up got the children

For breakfast and snacks.

Our friends now arrived

In two cars for to carry

Our family and baggage

Down to the air ferry.

As into the terminal

The bags they did carry

The agent just smiled

And said “Please do not tarry.”

Although overweight

And completely befuddled

We parted from friends

While our Danny was cuddled.

As we got on the plane

And prepared to depart

We said to our friends

“Goodbye” from the heart.

After our first

stop in England and a walk in the hot Phoenix sun (and a trip to the restrooms)

we were off again for Denver. The feel of solid ground did wonders for John and

he almost enjoyed the next leg of the trip. He even looked out the window. The

boys got one of their few views of snow as we crossed the Rockies. They were

quite fascinated. What concerned me

however was the fact that we were a half hour late and we had a half-hour plane

connection to make in Denver.

Originally it was

an hour and a half wait and I figured this would give us time to eat

lunch. However, that great institution

Daylight Savings Time came into effect two weeks before departure. United changed their clocks but not their

schedules thereby advancing their flights an hour (by the clock). Western flew

by the sum and changed both clock and schedules so we left a clock hour later

than planned. Now we were a half hour

late so I gave up the idea of eating. I

began wondering how to notify our relatives from Des Moines who were going to

pick us up at Omaha that we might be slightly (about 4 hours) late. Of course, I couldn’t work up a first-class

stew complete with anti-acid stomach pills because Charlie, now perched on my

lap, kept wondering what all those buttons were above our seats. I just became

aware of his curiosity when the Stewardess showed up and asked us if she could

be of assistance. I could think of fifty dozen things she could do; answer

Charlie’s questions, get the candy off of Bill’s jacket, calm John’s nerves, or

rock Dan to sleep. However, I answered

in the negative and wondered what brought her along at this time. After all she had already made John, Tom and

Bill Honorary Pilots and since the management miscalculated on the ratio of

boys to girls in the “children’s emergency packet for stewardesses” she had

made Oblivious Charlie Honorary Stewardess. They wore their badges proudly.

She left with a

somewhat bewildered expression only to appear again ten minutes later. About now it dawned on me why she was “on

call” and it dawned on me that maybe I wasn’t aware that she had been called.

So five cups of milk were distributed all around. Then I told Charlie you don’t

just punch every button you see (as I turned off the seat lights.) I was just telling him for the twentieth time

that the plane was not going to fall out of the sky when the “Fasten Seat

Belts” light went on. After getting him fastened in I had to start the old

routine again that this was not England but Denver.

As the door was

opened the gateman said “all passengers for Omaha follow me”. We joined, in

fact we were the greater part of, the parade (as well as being the least

disciplined). Except for six well

distributed single seats the new plane was already filled with impatient

passengers. John found a seat well

forward, Tom well aft, Bill amidships, Mom and Dan were inseparable in a single

seat, the stewardesses gave up their double seats to Charlie and me. This was, of course, to be expected but

nevertheless I was a little annoyed. I

am a 100,000 miler on United and had made reservations weeks in advance. In the past I had often been quite put out at

seeing double seats roped off “Reserved for People Traveling Together”, and

thought this would be my time to benefit by their custom. But, in any case we

were lucky that they waited for us.

In fact the wait

had just begun. It seems there was one more seat and two potential passengers.

A corporal on emergency leave and a woman who for some reason preferred

stopping at Omaha, Milwaukee, Cleveland, and Philadelphia before arriving at

New York instead of transferring to a plane that left one half hour later but

arrived in New York non stop an hour earlier.

After much persuasion (80 minutes worth) and promises of many telegrams,

etc. she was convinced, the corporal got on, and we took off.

The candy we had

received before take-off now became our lunch and Charlie and I dozed off. I was awakened by some well-known bumps and

looked out to see clouds and rain.

Luckily we were close to Omaha but not close enough. I looked around to spot Tom and saw an

ashen-gray face, an anxious stranger, and a hurrying stewardess. We were strapped in for landing and I could

do nothing. In fact, upon landing we couldn’t compete with the crowds and had

to wait for the plane to clear before we could get to Tom and help him gain his

composure. We sent John off to tell our relatives we would be along (but of

course he didn’t recognize them nor they him). However, we soon got off, met

our relatives and while I guarded our thirteen pieces baggage my uncle and

cousin went off for their cars to get us (and bags) loaded into.

Many hours, words,

miles, chicken dinners and rain drops later we were carrying thirteen bags and

two boys into a large farm house in the middle of Iowa. The slightest touch on the locks of the

largest bag caused it to pop open of its own accord. Then John’s green, Tom’s

purple, Bill’s blue, Charlie’s red, and Dan’s yellow cloth sacks with sleepers,

socks and underwear were duly issued. It didn’t take long to get Tom and Bill

settled in bed in an upstairs room.

Charlie and Dan

were now awake and had discovered the staircase. They proceeded to explore this novel new

plaything. Charlie confided that he liked this England. John soon gave up and

finally only the 2 oldest and 2 youngest remained awake. The oldest on habit

alone, the youngest to run off the undissipated energy resulting from being

cooped up all day inside moving vehicles.

Finally welcome

sleep came only to be rudely interrupted by Iowa’s famous thunder and lightning

storms. Luckily all boys slept through

it except Charlie and he wanted to go home to San Diego right now. We had lived

in California long enough now to have five “native sons” and they hardly knew

of thunder and lightning and we had forgotten how frightening such a storm can

be. The lightning lit the room well even

if only sporadically but the noise, Charlie’s was continuous. We could

occasionally hear the thunder above Charlie and we could sympathize with him in

his desire to “go home”.

So ended our first

day, and our first 2000 miles. There is nothing like a three year old’s cry

wanting to go home to make you wonder about the wiseness of the decision to

tear up seven roots, five young ones, and transplant them for a year. At this

point four were oblivious, one was vocally and two were tacitly doing some

serious thinking about home in the placid air-conditioned state on the

Pacific. And more than 4000 miles yet to

go and sixteen months. Wonder what the ‘49’ers thought after a month’s travel

westward?

The boys loved the farm,

although farms aren’t what they used to be. Whereas I rode the horses as they

pulled the corn cultivator, the boys rode with Uncles Art and Glen on the

tractor. In fact, John made a quarter

“helping” Uncle Art on his tractor pull a car out of the ditch (after the

rain).

Long before any

sensible Pacific Timers (only 1 day but 2 hours removed) should be getting out

of bed, the Central Timers and three boy Pacific Timers were up romping around.

What with hay lofts, mud, cellars, mud, tractors, mud, a real working pump

(water, that is), more mud to explore and develop, there was no time to tarry

in bed. So when we got navigating again

the boys already had gone through one breakfast and one change of clothing

(mud, you know). Before lunch all the pigeons had been frightened out of the

hayloft ten times, the squeak had almost been worn out of the pump, the cellar

had been explored and discoveries of potatoes, pickles, and mouse traps made,

and Charlie had gone exploring, quite unknown to anyone else. We soon became

aware of a curious lack of youthful continuous questioning and decided someone

must be missing. Sure enough Tom spotted him giving the neighbors hens a good

chase. Charlie had never wandered off before, but, of course, he hadn’t the

provocation. He found the “chicklies” on the neighbors farm, a quarter of a

mile down the road, quite more attractive than the large rather over-friendly

dog at Uncle Arts.

A trip to Uncle

Glens found more wonders of the world, cows, not the milking kind, the eating kind,

and pigs and chicklies. But still the dairy delivered milk, butter, and eggs to

the door. It wasn’t like the good old days.

However, one thing

hadn’t changed. Wherever there are pigs there is mud not just ordinary mud but

hog wallows. And wherever there is mud and boys, especially city boys, there is

magnetism. We soon heard a wail and looked out to see a boy, it turned out to

be Bill, already tarred waiting to be feathered.

To say he was

covered with mud was doing him an injustice, he was dripping mud. He had done the pigs one better. He wasn’t out of action long.

One of my cousins

was old fashioned enough to milk cows and gather eggs and this saved the

day. We arrived late, (with five boys

you usually arrive late), and the eggs had already been gathered. But since little boys with big eyes don’t

come often, they ungathered some eggs and took the boys around to regather

them. Our orientation seemed to fail on

Charlie on two points. Why don’t the

chicklies eat the eggs? He couldn’t be

convinced that “hens lay eggs for gentlemen” to eat and not for hens to

eat. A similar misunderstanding occurred

with milk and cows. Charlie saw little

calves drinking milk from a bucket and wondered why they bothered to feed the

older cows corn, oats and hay. Why not

milk? He obviously had ideas of his own

about perpetual motion.

Another aunt and

uncle ran a small town variety store complete with cap guns, squirt guns, jaw

crackers, milk shakes, and of course books (coloring and reading). We had never bought guns, cowboy outfits,

hula hoops, nor Davy Crockett hats for the boys. We figured, and quite correctly, that

Christmas and birthdays, relatives and friends, would see to it that our boys

would be boys. And so the blanket

invitation, one toy for each boy, caused quite a raid on the arsenal

armory. We drew the line on squirt guns,

the range is too great, the missile too dangerous. But we did hear bangs and saw assorted gun

play for many a day.

So much for

Iowa. We left dad’s folks on farms for

mom’s folks in a small river town in Illinois.

River barges and trains took over from tractors and haylofts. And Uncle Dodd had a pony (why not with five

small children of his own) and a pony cart.

But the climax came

when,

There were two families seven in each

Whose fathers read Mark Twain

Our oldest boy, too, had read

Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn

So when in Illinois one day

The families were together

Said Dad to Dad why not today

In station wagon gather

Two moms, two pops, two babes eight kids

For Hannibal departed

To see Tom’s cave and Clemens’ house

In wagon were they carted

Before proceeding very far

The clamor rose for food

So in they drove at drive-in

For hunger of the brood

Two dozen hot dogs, mustard please

One dozen chocolate shakes

To make the menu quite complete

Six packs potato flakes

For that one car the waiter said

Then looked or rather listened

Then set to work at double speed

With sweat his forehead glistened

While mamas kept the cups upright

And daddies ate the extras

The kids again began to play

Then started in the questions

Were Tom and Huck and Injun Joe

Real folks or story people

Will we get lost in Tom’s big cave

Is there a tall church steeple

Then finally cross the

A broad majestic river

And in the bluffs south of the town

Tom’s cave in which we shiver

Judge Thatcher’s room and Mark Twain’s house

Museums and statues too

Then heavy eyelids old and young

The sky an orange red hue

So once again like sardines packed

Yet thoughts of food did gleam

So homeward bound in Pizza shop

Six pizzas, then ice cream

Then miles and hours later on

A quite car at last

When small limp figures off to bed

The great adventure past

I left mom and boys

with her folks and proceeded on to Ottawa for the spring meeting of the

Acoustical Society of America (the first time in its thirty year existence it

had met in Canada). To the Navy, however, Canada is a foreign country and

certainly not a place for any American Society to meet. For every meeting we have a red tape snarl

but when in Canada the odds are insurmountable. This is the trouble.

It is the general

policy of the Navy to send no more than two people from any one activity to any

one professional meeting. This means that theoretically the Bureau of Supplies

and Accounts can send two and our lab can send two. It so happens our lab is one of the major

research and development labs in underwater sound, communications and speech

and hearing. Because of this San Diego,

twentieth in population, is fifth in members of the Acoustical Society. Also it can boast (at this writing) the

president-elect, two of the ten technical committee heads, and the head of the

membership committee, probably the most important non-technical committee (it

elects fellows). And usually at least

five papers are submitted by members of the lab. In addition to this there are

always so many papers read at a meeting that at least three meetings are run in

parallel. So of the two authorized to go one must be in two parallel technical

sessions at once often giving papers in both, while the other must attend the

other technical session at all times plus attending many administrative and

technical committee meetings. The two must

attend everything because they are obliged to report back to all interested

parties, who didn’t go, exactly and in detail what transpired in every

session. Even the Navy Department

realizes this and usually officially sends four or five people while the lab,

by some method, usually manages to get everyone giving papers, or holding

important chairs, to the meetings. This

always involves many letters, phone calls and in general probably costs as much

as at least one attendee.

However, when the meeting

is in a foreign country another complication develops. This one has for a background the absolute

necessity for a majority of our senators and representatives and members of

their families, to inspect and/or investigate Europe at the close of every

session of Congress. Taxpayers object to

this and since we are a democracy the lawmakers on their return say quite right

it is scandalous for government employees to travel at the taxpayer’s expense. So they notify the Defense Department (who

furnished the lawmakers transportation) don’t let us catch any of your

employees gallivanting around in foreign countries. So when our American Acoustical Society met

in Ottawa (on a straight line between Minneapolis and Bangor and all of 50

miles from New York State) orders came down one member at foreign

meetings. Since our lab can’t write

foreign travel orders without Washington approval we were had. The lab sent my boss, membership committee

chairman, and me to visit labs and scientists at Syracuse University and

allowed us to take a week’s leave without pay while we slunk across the

border. We arrived in Ottawa (I won’t

say how since I don’t wish to incriminate innocent fellow conspirators) at 4

P.M. on Wednesday afternoon and I didn’t get outside the hotel in which our

meeting was held until 3 P.M. on Saturday.

During this time I presented a paper, chaired a technical session, met

twice with the executive council, met with the technical committee I chaired,

and with two others of which I was a member.

A most relaxing way to spend leave without pay. American ambassadors aren’t the only ones who

sometimes have to sacrifice their time and money to carry out their

duties. Oh well, it could have been

worse. The meeting might have been in

Vancouver which I haven’t already seen and then I would have boiled over since

I am an inveterate sightseer. I did see

the surroundings of one street on the way in and the railway right of way on

the way out.

My mother met me in

Ottawa and we traveled on to Montreal to meet Dodd who heroically brought Mary

and the boys (and his wife but not their five children) from Illinois. I shared

but one night of their motel existence. “Accommodations for five adults and

five children please” and “Where is the nearest restaurant?”

After a week’s

separation John had to tell me how they towed Uncle Dodd’s car away at Niagara

Falls. Apparently he’d parked it quite innocently in an unauthorized place.

This misinterpretation of signs cost him five dollars.

And Charlie told me

everything. He never stopped talking. Dodd said he had Charlie sit with him

when he was in danger of falling asleep while driving. Charlie’s continual barrage of questions kept

him quite awake. During the trip Dodd had retaught Charlie his Sunday School

song—it now went (at top voice)

“What do cows do

Oh don’t you know

They lay large eggs

To help us grow.”

By now Charlie had

more or less forgotten about “going home” but the thought of boarding the ship

tomorrow made John think more of home. The utter finality of casting off for

across the Atlantic had finally come home to John.

We had no

difficulty oversleeping (we hadn’t for eleven years) and missing our ship. Even so we weren’t the first on board. Preening up five boys isn’t done fast or easily. We had but one bad moment when I couldn’t

remember where I had put the tickets.

But a thorough rummage through all pockets located these and so began

the parade on board. It had aspects of

Cub Scout day at dockside; a Memorial Day parade (tears for the departed or

departing); and an African safari (14 bags, one up, since my mother had brought

one full of emergency foodstuffs).

The Empress of

England is a new and beautiful ship and our tourist class cabins were

elegant. Uncle Dodd, who had been a

purser in the Merchant Marines, soon showed us topside, the afterdeck, the

promenade deck and in general was in his glory answering all Charlie’s

questions.

But soon the “All

Ashore” call came and after hurried pictures and parting words, seven of us remained

onboard and three found vantage places on the dock. Ever since my short visits to Montreal and

Quebec during World War II I had looked forward to sailing down the St.

Lawrence, and especially the leaving of Montreal. When Uncle Dodd, Aunt Marilyn, and Grandma

Webster were out of sight and John was sobbing (he didn’t like major changes in

his environment) and I was getting a good vantage point to see the sights the

announcement came, “All first sitting diners report to the restaurant”. Half way to Quebec I got topside again.

Our first lunch was

quite trying on our table companions and a little disturbing to our

steward. He was prepared with high chair

but hadn’t all the answers for Charlie.

Our major problem was understanding our waiters English English and the

general routine of English meals.

Children’s high tea baffled us most. So the children have tea at 5, then

what? Also which children? And who feeds them? The idea is fine and standard

British operating procedure. In theory it works this way. The children,

assisted by a nanny of which we had none, eat early and go off to bed. “Daddy

and mother dine later in state, with Mary to cook for them, Susan to wait.” On

board it worked something like this: Dad and Mom and all five boys report at 5

expecting tea and biscuits, and find hard boiled eggs and/or cereals and cream

with bananas, apples, oranges, etc. and milk, and then biscuits (cookies)

cakes, or sweets (candy). The trouble was on the first day we didn’t know this

meant no supper or that this indeed was the boys’ supper. In fact, we wondered

why they wanted to spoil the children’s appetite just an hour before supper.

Also how do you eat hard boiled eggs?

The British children went right to it, but we didn’t know how to

de-shell it and with what implements to attack it. And who wanted cereals and

milk at 5 P.M.? Guarded questions to our

fellow, but British, passengers soon gave us the clue this was the children’s

supper. The children WOULD NOT be expected at our supper. This gave us 15 minutes

to see if Tom, Bill, and Charlie would like the chaperoned playroom. They

wouldn’t. And if John thought he could entertain Dan (age 1 year 2 weeks) in

our stateroom. Dan would have been acceptable in the play room if asleep. But

as crying is contagious, he wouldn’t otherwise be welcome. I don’t remember

exactly how we got away, leaving all five boys in our cabin, but needless to

say we hardly enjoyed our first six course dinner.

By the second day we

knew the meaning of high tea and introduced the boys to the play room early in

the day. They were neither completely averse nor adverse, but we did get Bill

and Charlie there while we hurriedly feasted.

Dining aboard the

Empress of

John liked the

swimming pool and cinema best. Tom and Bill the afterdeck where ropes and pegs

were available and occasionally shuffleboard. Charlie liked to walk around or

sit in the deck chair and ask, “What happened to the hair on that man’s head?",

"When will we get across the ribber?”, “Does that man have more cake?”,

“Why is that lady so fat?”, “Why can’t we go in there?” Dan liked to crawl on the deck and especially

to play in the water in the scuttle. Dad would have liked to sleep. Momma was

perfectly happy. No cooking, no dishes, just washing and ironing (which she

says she enjoys). She saw her first movie, except for Ivanhoe at the drive in,

in eight years and found many English mothers to talk to.

On the fifth day

came sea state 8 and ashen gray boys. My cure, Dramamine and a horizontal

position, was not working for the boys so at their insistence and much against

my better judgment we went to the afterdeck for shuffle board. There were very

few people about. John, Tom, Bill, and I played while Charlie collected the

pucks. It was fun trying to counter the roll of the stabilized ship. And the

mist on cheek (and glasses) felt good (but looked misty). The cure worked, the

boys kept their food down and so did dad.--(who still preferred his horizontal

method).

Johnny couldn’t go

swimming alone, so although mom was an excellent swimmer, dad got to go

in--glasses and all. Without glasses I couldn’t tell which boy I was supposed

to be watching. With glasses I couldn’t have done much had he sunk from sight.

Not to be outdone, John wore his non-waterproof watch in. It hasn’t worked

since. Charlie, Bill, and Tom watched and in the shower room Charlie asked,

“Why does that man have hair here (chest) and not here (top of head)?”

The cinema turned

out to be marvelously timed. Charlie was much too engrossed by the ship for an

afternoon nap. But after 10 minutes in the cinema he was asleep.

From the second day

on we were, you might say, well known. We made the longest passenger list, the

longest parade, and Charlie made the most continuous sound. We were approached

by grandmas, granddads, moms, dads, the whole lot. Without our five socializers

we probably would not have met a soul, but with them we were called by name by

half the passengers.

Perhaps our trip

across the Atlantic can best be summarized by the letter I wrote back to my

colleagues and church friends while on board:

Empress of

0930 Brit Summer Time

0130 Pac Daylight Time

Dear

Dave et al

Glad

to receive your letter which I received on boarding. Sailing is wonderful

except for changing the kids internal clocks. Each night for 5 nights we set

the clocks (the ticking kind) ahead one hour. Each night the kids get to sleep

about an hour later. Last night by 2330. This morning (which is no different

than all others) Mary and I, with the aid of those infernally noisy stewards

and stewardesses (who keep knocking and saying cheerfully its seven thirty,

with a rising inflection yet, all hands are British) flop out of bed and THEN

get the kids up. This morning we fed them (midnight your time) but were never

sure whether we were shoveling the food into their otherwise closed mouths or

eyes.

Now

all but Tom are back asleep. Yesterday it was all but Charlie - in each case, Daddy

likewise happily stayed up since the sign reads, “No children allowed on deck

without their parents”. Dan is the worst; he got to sleep at 0300 yesterday,

but by 0130 last night. He and mommy are now asleep in the adjacent cabin.

I

began taking Charlie to the 1415 movie so he would get some sleep which helped

him, but at least one of the kids enjoyed the movie and I’d have to sit through

it (Onionhead, Gidget, etc.). Of course, when they showed Richard III, everyone

was sick so I missed it.

None

the less, this is really the way to travel. For the same fare as by air we get

3 x 7 = 21 meals. Last night I had Tomato juice, Salmon, Roast Mutton with

vegetables, scones, caramel sundae and tea.

I skipped the soup and salad courses since I took the fish course and

Mary keeps thinking me a pig (especially when Alec Guinness, our waiter) brings

me a piece of layer cake to go with my dessert. Dave would love this. I still don’t completely understand the menu

- it has an appetizer course olives et al, soup, fish, then an entree and a

joint and a releve. Then salad, dessert

and tea. The releve seems to be fowl but the difference between entree and

joint I don’t get. I’ll have to ask Alec at noon.

The

deck steward sidled up to me last night and whispered something which, upon

explanation, turned out to be, “Do you want to take some spirits ashore”. He

strongly advised it since a fifth of Scotch would cost me 27 shillings, but 35

ashore. A shilling is 1/20 of a pound which is equivalent to $2.80 ± depending on

which way you’re sailing; expensive going to England, cheap when coming home. I

told him no thanks, my boys are too young.

I’m

king on board; no one has as many children and Dan always smiles at the right

time and Charlie keeps saying, when showering after a swim, “Look Daddy that

man has no hair” in his usually 100 db voice, or “I don’t like this ice cream”

(which is the chef’s special pineapple, not the vanilla he has at all other

meals), etc. Charlie who landed in England first at Phoenix, then Denver,

Omaha, etc. now wants to know “When are we going to get across this ribber?”

The

bath steward just stood with his mouth open when I requested 5 towels with my

bath and as J, T, B, C and Dad filed out of the bath (bahth) he had 2 other

stewards watching just to prove how big the bathrooms are on his deck.

Time

to wake them up again and go to Church. I can hear Charlie now, “Daddy where’s

the choir” or some such apt but loud remark.

JOHN

Even with five boys

however we agree with the travel books on sea crossings. They say you wonder before you board what

you’ll do with all your spare time. Once on board you wonder how the hours slip

by so fast. And the night before landing

you wonder what happened to those short glorious days.

At all previous

stops we had told Charlie “No this isn’t England” so by now he was wary. He

didn’t see why Liverpool should be England if all the other places were not.

But we soon persuaded him and he concluded that England is across the big

ribber. For the next few days his troubles began again. Cambridge was not in

England. It wasn’t on a big ribber and

our Empress wasn’t there. To this day Charlie insists Cambridge is pronounced

with an a as in lamb. He heard us say the city was named because it was the

first (or last) bridge across the Cam (as in lamb). To him (and more power to

his logic) the name is Cambridge (a as in lamb).

Celebrating in

Stateroom on the Empress of

Driving in England

is a not to be forgotten experience. As

the travel literature says, you do not rush through England, but around every

leisurely corner you have the opportunity to see the quaint countryside. They

are completely correct in saying you do not hurry, but getting the opportunity

to see anything other than the road is virtually impossible. Unless, of course,

you are foolish enough to do what every tenth Englishman does as his God given

right, namely just stop right smack in the middle of the traffic lane to see

the sights, to adjust the headlamps, to eat lunch, to sleep, or just because he

fee1s like stopping.

They have signs on

major highways (the ones they paint center lines on) that say “Layby 1/4 mile”.

This means that the road will widen by about half a lorry width and a trash can

(dust bin) will be provided for those desiring to walk 20 feet after eating

their sack lunch (tea that is) to deposit their litter,. These laybys are well

patronized, much more so than our “Roadside Tables” and for good reason. After

driving through English traffic for say two hours (40 miles) one does feel the

need for a rest. Parking is completely impossible in towns (except by just

stopping in the middle of the road which is universally done) and roadside

“Dairy Queens” or “Steak and Shake” shops are non existent. The pubs are only open for some very limited

times and so everyone packs “tea” and stops at a layby. However, since more people want to stop than

there is layby space, they just stop on the road.

To show how deep

rooted their tendency is to just stop in the traffic lane on the road let me

cite the first two fatalities on M1, their one and only freeway, which opened

after our arrival. It came as no

surprise to me to read: 1) That a van had some minor ailment and had stopped,

not on the verge which some reports said is not wide enough for a vehicle to

pull clear of the traffic lane, but as on all English roads, in the traffic

lane, 2) That a repair vehicle had come and stopped in the traffic lane; and 3)

that two lorries free for the first time of traffic worries were running “flat

out” in a slight mist; and 4) inevitably had crashed into the repair vehicle in

the traffic lane. This must have caused a minor revolution because soon after

this, and I quote from a Cambridge newspaper account “DRIVERS SLEPT ON Ml, Five

drivers said by police at Luton today to have been found asleep in their

vehicles on the M1 were each fined 5 pounds for parking on the Motorway”. I have since driven on M1 and find they are,

belatedly, widening and strengthening the verges (with crushed rock) so that

disabled cars (and sleepy or hungry drivers) can experience the novelty of

pulling off the road to stop.

Our first

experience was as follows: We got off the boat in Liverpool and paraded down

the gangplank, and through customs in jig time.

I am sure they figured anyone traveling with five small boys is too busy

to smuggle. We had arranged in the States for a rented car to meet us at

Liverpool (much against the advice of all our English friends). After all

Cambridge is only 160 miles from Liverpool, at most a four hour drive. We soon

saw a small man in a large overcoat (on a sunny very warm day late in May) who

had obviously spotted our entourage and was making his way toward us.

“The car is just

down the street" he said. "How many bags do you have”?

“Fourteen”.

“Fourteen”?

“Well, actually

three are brief cases, and two are little overnight bags”.

At this point we didn’t tell him one was a footlocker and one a duffel bag with three sleeping bags packed inside.

“Righto, I’ll get

you a porter”.

"O.K"

So Mom, Dad, John,

Tom, Bill, Charles, and Dan, plus a porter with 14 bags arrive with the by now

somewhat anxious little man at England’s newest and largest Consul complete as

per instructions with luggage (roof) rack on top. The porter sort of shook his

head and as quickly as possible made his exit, dumping all the bags in a heap

on the kerb (curb).

The little car hire

man now saw he was in it for better or worse and he actually accepted the

challenge in good grace.

First the boot

(English for trunk). Yes it held middle sized bags, the contents of the duffle

bag (by taking the sleeping bags out and stuffing them alongside, over, under,

and around the other bags).

By standing all

bags upright instead of laying them down, we finally coaxed the footlocker and

three large bags in the luggage rack. This added about 3 feet to the height of

the car. I say about 3 feet because by the time all bags and boys were in, the

car was at least 4 inches closer to the ground than when it stood in all its polished

splendor unsoiled by our presence.

The three

briefcases and two overnight bags went in the back seat with John, Tom, Bill,

and Charles.

And now came the

instruction period (if Mom and Dan could just stand outside a minute). This was

the key, it went here, the brake was still right and clutch left, but the gear

shaft was on the left since the steering wheel was on the right. After much

explanation I got the idea the gears were like ours except left handed.

He started to

explain the hand signals but soon gave up. Instead of three simple signals like

we have; arm down meaning I am slowing down or stopping, arm straight out, I’m

going to turn the direction I’m pointing; and arm up meaning I’m turning the

way I’m trying to point (but cant reach up over the top) and in any case means

O.K. for you to pass, they have, among other things, two waving signals, one of

which means “I am ready to be overtaken” (English for passed) which is the same

signal truck drivers in the States (and lorry drivers in England) give you when

they can see the road ahead is clear even when you can’t and means come on

around old buddy and be kind to truck drivers when the next request for a pay

raise (American for rise) comes around. The other wavy signal means something

else (I’m still not sure what). It doesn’t much matter what it means anyway,

because if you are more than 10 feet back you can’t tell one wavy signal from

the other. And later experience has convinced me that in any case, don’t be

fooled by the wavy. It means I’m ready to be overtaken but it doesn’t mean the

road is clear, except when given by lorry drivers on the open (and I use the

word loosely) road (I won’t use the word highway). So as far as I can make out

the English hand signal means about what a woman’s hand signal does in America,

namely that the window is open.

Anyway we

compromised. He finally said “Use the turning indicator lights.” This I did.

Detailed study of

my road map (helped by ten hands and six voices) convinced me the shortest way to

Cambridge from Liverpool was to drive west. That is, cross the Mersey River to

Birkenhead and avoid all the large cities, including Liverpool. Our dining

steward in the Empress told me the way to cross the Mersey from the dock was by

tunnel.

So knowing how to

drive from the wrong side of the front seat, and where I wanted to go, I was

ready to bid our little man farewell.

I had noticed that

we were parked on the incorrect (English) side of the street, namely where we

should be, on the right. The little man said that was O.K. You parked on whatever side of the street you

wanted to in England. I later found that

truer words were never spoken. You not only park where and when you want, you

also wait (park for less than 20 minutes) anywhere you want, including the main

traffic lane of the main highway, within 3 feet of intersections with traffic

lights and turning lanes, and in fact any place other than on verges (English.

for shoulders). As far as I can see, verges are used for absolutely nothing,

the only unused land in all of England.

After politely

refusing my offer to drive him to the nearest bus stop or railway station, the

little man vanished. Mary said he

crossed himself and ran. We were ready to go. John said why didn’t we take the

train. Tom just gasped. Mary clutching Dan tighter than usual, climbed (down)

into the front seat and we were off.

Within a block we

hit our first round about (English for traffic circle). The English Highway

Code says there are no right of ways (or left of ways) at round abouts. In

other words, they don’t want to be responsible.

The only real highway law in England is if you are in an accident and

were moving you were wrong. We later read of a case where a bus driver was

fined because he couldn’t stop soon enough to avoid hitting a car that had

stopped, not on the verge, but right in the lane of traffic, to adjust his

headlamps, right over .the brow of a hill. The man that had stopped was not

fined.

We finally decided, since cars were overtaking (passing) us

on both sides, to disappear into this maelstrom. Our

problem was where did we want out. We

chose the third exit. We crept along at the average pace, about 15 m.p.h. until

the next intersection and then found the secret. There are so many cars per

street that at every intersection there is a Bobby (policeman, you see Robert

Peel established the constabulary years ago and these were Bobby’s boys). Our

system; at every corner as we crept by the Bobby, we looked bewildered, spoke

American, and asked for Mersey Tunnel. He always answered in some completely

unintelligible speech that ended “You can’t miss it” but luckily he always

pointed. Finally instead of pointing straight ahead one pointed left, and we

saw hundreds of vehicles concentrating on one poor little double laned street.

Once committed to

the tunnel, the fast lane since we were not a lorry (at least in name) I became

aware of three things: first Mary was getting closer and closer to me and

saying “Do you know how close you were to that truck”? (American for lorry).

Second, unlike American tunnels, this one was not lighted (except conceivably

for cats) and again, unlike American tunnels where if there is no light you put

on headlights, here no one had on headlights but instead they had on side

lights (parking lights and actually the closest thing possible to no lights at

all). Driving in virtual darkness, in fumes as thick as fog, with candles borne

by lorries busses, and cars coming at you at 30 m.p.h (about the only spot I’ve

ever found in a metropolitan area where traffic can move that fast) had even

the captain of the ship a little uneasy. Then Mary said “The gas gauge says

empty” and so it did. Anyone knows when you rent a car it has a full tank of

gas, but.

We did emerge

safely from Dante’s Inferno, we did find a petrol (gas) station, and our next

problem was a rope to secure the bags on top. Who sells rope? Hardware stores

of course. We saw green grocers, chemists, and finally obviously an

ironmongers. So a rope and our first experience of stopping (behind an already

stopped car) and making a one lane road out of the major artery out of town.

This turns out to be more rule than exception.

Now our pulse rate

could return to normal. We were tied down, full of petrol, on the road to

Chester, and it was only 11 o’clock. We’d be in Cambridge easily by 4 or maybe

3.

We now had time to

realize that England is indeed a foreign country. The cars including our own,

were a sensible size, not domesticated tanks. The average age of car, lorry, or

bus was ten years older than ours. There

were people, bicycles, cars, houses, everywhere, no wide open spaces. Houses

were dotted with chimneys, and chimneys were full of chimney pots (flues). We

next saw a goods (freight) train with a steam engine. This really stopped us.

Four wheels per wagon (car) many of them spoked. Chain and bumpers for

couplers, and wagons about one third the size of our eight wheeled freight

cars. We actually couldn’t believe it and thought it must be a small and branch

line. It wasn’t.

Then came the strange

signs. Acute Bend, Road Up, Dead Slow, Road Works, Layby ¼ mile. And Free

House, No Coaches, Tea now being served. On a car ahead, Please Pass Running In

which means I’m breaking in a new motor (or car). Free House means we are not a

pub (tavern) that sells only Tolly, or Worthington, or Bass Ale, but whatever

we please.

Our fist near miss

came in Chester, an ancient town with city walls, overhanging first (second)

floors, etc. It happened like this. In

the States and California in particular, there is one golden rule of driving,

never just change lanes. Since it is legal to pass (overtake) on either side

(preferably on highways with painted traffic lanes, but actually anywhere where

vision permits) you soon get conditioned (by the loss of a fender, or at least

by loud honking and squealing brakes, not your own) to move forward in a

straight line. Before moving to left or

right you look in one, two, or three mirrors, signal, and pray, and in general

you don’t swerve. In fact the only accidents I’ve ever had were two gentle

bumps on cars who pulled over or stopped to make a U turn in my lane of

traffic. In both cases I could easily have avoided them by pulling into the

next lane. But since I knew I would just barely tap them, and by pulling out I

might get myself and others killed, I maintained straight ahead.

Back to Chester.

Being new to the left hand side of the road I was staying very left, about 18

inches from the kerb (curb), when no cars were parked there (which actually

wasn’t very often). As I was half way

across an intersection what should dart out from the side street which in

America would be a STOP street but a lady on a bicycle. She looked neither left

nor right, which I’ve since found to be an almost universal rule. During my

twelve months in England I saw only one bicycler who looked before turning into

the line of traffic from a side street. Anyway, this lady in Chester turned the

corner to join me in my direction of travel. Obviously Englishmen have been

conditioned for generations to swerve to miss such obstacles. I’d been

conditioned to accept a known risk rather than swerve into possible oblivion.

She and I arrived at the opposite kerb in a dead heat, me 21 inches from the

kerb, her 3 inches from me. I was listening for the crunch on my offside since

I did deviate 3 inches, but all I heard was unladylike speech from my onside.

This really didn’t unnerve me much since I’m used to missing objects by narrow

margins. I’m not sure what it did to her, but I’m willing to bet she still doesn’t

look before turning a

corner into a busy street. After all

statistics are statistics, and as I’ve said I’ve only seen one person, a school

boy about 15, who has ever looked and in fact he slowed down.

We soon learned the

only thing you don’t see in England is an open road. You can expect over any

hill or around any bend in country or city to find a car or lorry stopped in

the road. And bends they have plenty of.

It is an axiom in England that if a road is straight the Romans built

it. I guess Romans either didn’t have cows or else had highway engineers who

considered themselves the equals of cows. That they were good road builders is

attested to by the fact that many of their roads, paving bricks and all, are

still in use.

I heard one story

over the B.B.C. news about a village who couldn’t get the shire road people to

come and repair the ancient Roman road through their village. The reply was

something like this: “We didn’t build it, we won’t repair it”. Whereupon the

ingenious parish council wrote to Rome, the Italian government, and asked if

they could come to beleaguered Britain’s help; copy to shire hall. Result; the

shire was shamed into fixing the road.

By the time we

figured out that tea was the generic word for food it was two o’clock. We were

about 60 miles out of Liverpool, 100 miles from Cambridge. We were hungry and I, the driver, was about a

nervous wreck. Instead of peaking between 65 and 75 dropping to 35 in towns, we

were peaking at 50 and then not often, and dropping to zero in towns where

parking and waiting brought cross country and city travelers down to one lane

so you wait for one direction to pass and then you sneak through.

A phone call to

Cambridge, we’d be a little late, then lunch. Then more creeping on.

At all of these minor

emergencies, that is a car stopped in the traffic lane to have tea, I noted one

trouble for Americans in English cars. Every time I intended to shift from high

to second, as I always do where when slowing down, I succeeded in signaling a

left turn, this because I was reaching for the gears with my right hand and

found the signal indicators and shifted them instead. Other Americans have

complained of looking in the wrong place for the rear view mirror, but for the

most part these are easterners who can survive without outside mirrors. I tend

to look left into my outside mirror before overtaking in the states and found

no difficulty finding the mirror in England’s backward cars.

At first I gave

them the benefit of the doubt and considered it just a wrong choice to drive

left not right. But after months of thinking it over I believe they are wrong.

First historically; knights in shining armour afoot or ahorse carried shields

in left hands and certainly bore right on any path when meeting and passing

anyone head on. To this day I believe pedestrians prefer to keep right, keeping

their right hand free for emergency uses. Ships, even in England keep right.

The most important lever in a car is the gear shift, it should be handled by

the right hand. When giving hand signals you should sacrifice your left hand

and continue steering with the right.

I didn’t find it

particularly difficult to keep to the left since actually in any tight

situation there was just room for one car and it could be anywhere left, right,

or center depending on where others had parked.

I came to two conclusions before arriving in Cambridge. The English road

system would be more catastrophic to California than a major earthquake. And

English drivers, pedestrians, and cyclists would not last one week in

California.

We had been

spectacularly unsuccessful in finding a house to live in. We had some good

leads but no lease in our pocket. We assumed that when an estate agent

(realtor) gave us the address of a house (they never take you to see one) we

could expect to move in if we liked it. It doesn’t work that way. If you like

the house he puts your name on the list with others who also like the house,

and then contacts the owner to see which tenant the owner prefers. This takes anywhere

from a day to a month. With five children we knew how many times we were apt to

be preferred.

We dearly loved one

ancient and rambling thatched roof ‘cottage’, six bedrooms, large garden (yard)

quarters for nanny, cook, and whoever else you could afford, and obviously

designed for large families. We were put at the top of the list by the estate

agent. He realized that a house built for families should be lived in by

families. He also realized he had one and only one house commodious enough for

our entourage.

The cottage

(actually called Byrons Lodge) had always been rented to large families (2 or 3

children) and he told us we could expect to get the house. “Go off to the

Continent and we’ll advise you of the owner’s decision and tell you when you can

move in”. In any case we liked Byrons Lodge so well that we didn’t seriously

look for another list to put our name on.

So off to the

Continent we went with a hope but no promise. Early in March I had contracted

(and paid for) a Volkswagen Microbus to be picked up (by us) in Hanover on 1

June. I had asked our La Jolla travel agent not only to book us across to

England but also on to Hanover. She had stated that would be unnecessary. Such

a short trip and so early in the season. Just book it in Cambridge.

Well, as is usually

the case when I buy travel tickets I had spent hours in advance looking at

ferry and train schedules and knew precisely how, when, and where I wanted to

go. My travel plans had been firm since April, and I had written the VW factory

to the hour when I’d be in Hanover. So,

as is also usual when I want some tickets, I get in line behind someone who

knows to the closest two weeks when his holiday (vacation) is, and knows in

general which direction he wants to go, and how much money he has to spend, but

no more. For a half hour I stood

listening to “Switzerland is nice in August”, “It would cost you 30 pounds to

fly but you do save so much time on the channel crossing you know”, “However

you can go by rail, crossing between Dover and Calais”..... My thoughts and

blood pressure were near the breaking point.

Finally my subconscious mind heard “Thank you, I was just making

enquiries, I’ll contact you later if I don’t take my usual holiday to Brighton”.

In a not too

pleasant voice I said “I want two and four half, second class, tickets from

Harwich to Hanover”. He answered something in English, which after

reverberating around in my mind for a while came out to be American for

“when”. I said 3lst May. His composure

which he had kept during the previous half hour of nonsensical generalities,

suddenly left him. “Why that’s only three days from now”. I assured him I was

aware it was three days hence, but that American travel agents don’t like

trifling trips, that the railway representatives on the Empress are not

interested in getting anyone beyond the range of the British Railways, and that

yesterday I was looking for a house. Well, he couldn’t promise anything but

he’d see.

After much hustling

and bustling he returned to say “Sorry no second class berths on the night

ferry, only first”. Since I was in no position to be fussy I succumbed and said

“I want one four berth cabin or two two berth cabins”. He replied “Sorry, all

fare paying passengers (4 years and above) must have a berth. And there are no

4 berth cabins, only 2 berth cabins are available. You will need two of these

and an additional berth in a third cabin”. I

asked him in a slightly irritable voice, “How would you suggest I divide our

family up into 3 independent self sufficient groups”. After a moment’s thought, he said, “Put the

two youngest with their mother, you take the next older ones, and the 11 year

old can stay alone (with a stranger in a different part of the ship)”. I asked

him if he had any young children. “No why?" he replied. I thought back to the airplane where if

someone had been with Tom we could have talked him out of his air sickness, or

at least comforted him. I thought of many other things too, and told him that

while traveling Mom and Dan slept together in one berth, Dad and Charlie in

another, Tom and Bill in a third, and John alone, 4 berths.

He said “Sorry, you

must have 5 berths”, which we got. I

don’t know who got a private cabin at our expense.

Now as to the

train; I agreed second class was O.K. Did we want reserved seats? Of course we

did. We didn’t want a separate boy in

each compartment. Anyway the cost is ridiculously low.

One half hour

later, the tickets were ready. You see in certain countries children under 3

ride free, in others under 4. Likewise

half fare ages vary from 10 to 12 to 14. Then of course, part first class, part

second. One and a half hours after entering to transact a simple business I

came out cursing American and British travel agents, British and Continental

Railways, and myself for not having my Volkswagen delivered in England.

Sunday noon, 31st

May 1959 (Memorial Day) we again loaded down our overburdened Consul, but not

as in Liverpool. Two bags of permanent things (like winter clothes, technical

books, and papers, etc.) were left in Cambridge. We had our last lunch in our guest house, and

set off for the American Military Cemetery outside of Cambridge for Memorial

Day Service. Mary and I had taught (and in fact met) in an Air Force Communications

School at Yale University during World War II.

We felt we owed a debt of gratitude to some of our ex-students who had

graduated with gold bars into operations out of England, never to return. It

was a nice ceremony flowers dropped from bombers, military bands, and speeches

(we left early).

We had to drive 60

miles (3 hours) to Harwich. Most of the

goods lorries (freight trucks) were off the road on Sunday (but more sightseers

were parked on the roads gazing) and our pace was better than planned, that is,

better than our revised plans made in England not quite up to our original

plans made in America.

In any case we

arrived in Harwich in good time with only one stretch of typical English Sunday

traffic. In late afternoon every third car in London is returning from an

afternoon (or weekend) at the seaside (beach). Since we were going to the coast

we just gazed in wonderment at mile after mile of bumper to bumper,

five-mile-per-hour traffic struggling home through Colchester.

We arrived in

Harwich about 6:30 and hungry. At Parkeston Quay, where we were to board the

ferry, there was no place to eat so we drove into Harwich for a snack. We

picked a place that looked common enough to tolerate 5 children, but we were

wrong. They informed us they were closing. So we crossed the street to a more

exclusive looking place and ate in leisure, watching the poor unsuspecting

potential diners approach the closed cafe, and indeed enter it and eat.

Ridding ourselves

of our rented Consul was no problem at all.

A younger small man was waiting at the quay, walked around it once,

hailed a porter for us to unburden it, said we’d hear through the automobile

club about any additional charges or rebate, bade us bon voyage, and was off.

The porter carried

our footlocker, duffle bag, and matched set of fit-inside-each-other bags (when

empty) and three brief cases (mine, the boys school work, and the boys car

games) to the customs man and ticket takers. We asked about registering

(checking) most of the baggage to Hanover and did so. From what I’ve heard since about letting

baggage out of sight I am probably the only traveler in the world who

registered his luggage and claimed it upon arrival without incident.

We were then ready

to board, and on sight of the cross channel ferry, Charlie’s eye lit up and he

shouted “There’s our Empress”.

The Empress of

Arnheim is no Empress of England. It is

older, smaller and dirtier. Our first class cabins wouldn’t hold a candle to

our previous tourist class accommodation.

This was to be expected but it required much explaining to the boys. Our

extra privileges (going forward on the deck below the bridge, and eating or

drinking in style, which we had neither inclination nor time to do) were short

lived and we were soon nested in. We never did see the cabin where our fifth berth

was.

After a hectic and

rushed breakfast we boarded the train to claim our reserved seats. We found the right coach and were proceeding

towards the seat numbers indicated when we came to a glass door marked “First Class”. Sure enough our reserved second class seats

were in the first class potion of the coach.

And there we were. No seats, and

no likelihood of seats since all second class seats except singles here and

there were taken. The conductor (guard,

Schaffner) saw the difficulty and indicated he would straighten it out once we

were underway. So we stood holding boys

and bags until half way to Rotterdam when he escorted us back to another quite

ancient and quite deserted coach and gave us a whole six-seat compartment.

We were fairly

happy until we made a few discoveries. Namely this compartment, unlike the ones

in our assigned coach, had no rug on the floor. Once Dan started crawling on

the floor we remembered why passenger trains improved so much when diesel

engines replaced steam engines and sealed windows and air conditioning replaced

windows that opened (and like ours usually could never really be closed). His

hands and knees were blacker than coal. Soon his face and clothes as well as

our clothes began to turn first splotchy black, then smudgy gray, and finally

rather polka-dot; dark spots on dark gray background.

The scenery was

wonderful, especially the haystacks with moveable thatched roofs. When full the roofs were way up high and as

the hay was used up the roof kept pace by dropping down on the poles that

supported it. The scenery inside was getting darker by the moment.

Up to this point

(two hours inside our first non English speaking country) we had no real

language difficulty. English is not American, but except for a few (thousand)

words that mean different things, broad a’s, a rapid pace, and soft voice

level, everything could usually be deciphered.

Except of course the English money system (or lack of system), but more

on that later. And we were now on a

train that met the cross channel boat from England. Anyway everyone says every

European knows English, especially on trains, in hotels, etc. I hadn’t even

bothered to take my German-English dictionary out of the luggage and put it in

my briefcase. Then came our first shock and minor setback.

A young man wearing

an apron entered our compartment and started spreckend Deutsch. I looked a

little startled but rose to the occasion and asked “Sprechen Sie Englisch?” To

my utter amazement he answered “Nein, Sprechen Sie Deutsch” and there we were.

Actually I had

studied German two years in high school, and a year in college. I also had

taken a special German course and translated a short book on the history of the

clarinet and had easily passed my German “reading” test in qualifying for my

Ph.D. I had also attended night adult school in San Diego (at a school two

blocks from my home) and had a delightful time listening to Frau Busch telling

auf Deutsch of her impressions of Germany. I had even been teaching German to

my oldest boy (and three of his school mates) so that he could better

appreciate our trip to Germany. Nevertheless I hadn’t expected such an abrupt

nor decisive change of gears into a foreign language.

After a lengthy

conversation where my most used words were “Ich nicht verstehe”, and “langsamer

bitte” I gathered he wanted to know did we plan to eat in the Speisewagen

(diner); ja. Did we want the erste (first) oder sweite (second) sitting; erste.

What did we wish zu essen (to eat), followed by a series of words about every

fifth of which I understood, like eggs, potatoes, and sauerkraut. I chose

something which included the word Eier (eggs) and he gave me a piece of paper

with a table number etc. and departed much more tired than he had entered (and

much later than he’d planned, I’m sure).

Then John, to whom

I was “Herr Schulmeister” himself, eagerly asked what transpired. I regained my

composure and triumphantly told everyone would eat at 11 o’clock and have eggs

of some type, probably an omelette.

Not long afterwards

as we approached the border between Holland and Germany, some uniformed men

boarded the train. Very shortly

thereafter the Netherlands immigration officials, after looking at my boys and

my own short hair cuts and my rimless glasses, asked in perfect English for our

passports. And then the German customs man in perfect Deutsch said something of

which I extracted the words cigarettes and spirits, and I answered

"nein" just as if I knew what he had been saying.

Somewhere in the

next ten miles we must have crossed into Germany. I had seen no massive

concrete pill boxes, barbed wire, nor even any ploughed ground. In fact I

hadn’t the vaguest notion when we entered Germany and believe me I was looking,

for four voices kept asking “Are we there yet”. It was somewhat disappointing

not even knowing. After all, every movie you see shows barricades, guard

houses, sinister looking guards, and you somehow expect a change in something

or another.

The change soon

came, we stopped in the first German town to change engines (and about

everything else). I expected things to really get efficient now. So we sat, and

sat, and soon noticed it was 11 o’clock and so I stepped off the train to spot

the Speisewagen and it was gone. Part of our train was going to Scandinavia and

part on toward Berlin. There must have been some mix up as to which cars were

going where, and maybe they had only one engine. It seemed as if this engine

must have gone to Copenhagen and back and was now ready to take us to Hanover.

After a forty five minute wait we were again eastward bound and also walking

toward the Speisewagen. Because of the delay they must have telescoped the two

sittings into one. In any case when we arrived our assigned table and all its

four seats was already one-quarter occupied.

I am not sure yet

how we did it but somehow our seven got themselves in the remaining space.

Luckily our unfortunate dinner companion spoke excellent English and either had

a good sense of humour or was exceptionally well mannered and well poised. He

seemed to half way enjoy the consternation threw into the diner crew and

entered into the festivities with gusto. He suggested and in fact ordered two

German brews for Mary and me (kind of a nerve tonic) and reordered one for himself.

Then after a chat with the waiter he asked if we had really ordered a

dill-pickle and potato omelette. I

acknowledged that we probably had.

Not too long

afterwards (in fact I often had the feeling that certain parties were anxious

to see us on our way) a giant sized platter came with the aforesaid omelette,

with ham yet. Actually we couldn’t have done better, it was wonderful and even

the boys relished it. All except Dan. He went to sleep. The dead weight added

nothing to the ease of devouring that typically huge German meal. Before the

ice cream came around Charlie was also asleep. We knew this might happen,

that’s why we chose the first sitting. Unscheduled events cause havoc in

families with small and many children.

Our meal was really

quite a success, thanks to our unexpected interpreter, baby feeder, spirit

lifter, and companion to the end (of the meal). We succeeded in waking both Dan